An allegory for our condition—The Human Condition I: No Greater Love

(This article first appeared at www.amazon.com on 13 Feb 2013)

The British film critic David Shipman described The Human Condition—Masaki Kobayashi’s 9.5 hour epic—as “unquestionably the greatest film ever made.” I raise that straight up, because any film calling itself ‘The Human Condition’ holds promise of great profundity; and praise as singular as Shipman’s indicates it may have fulfilled that promise. So does it? I will concentrate on that question, but before I do, let me deal with some formalities first...

The 9.5 hours do not run unbroken. Whatever its merit, I think we can be thankful for that. Kobayashi followed the structure of Junpei Gomikawa’s mammoth novel and divided the film into three separate parts—the first of which is No Greater Love, a title taken from Christ’s description of unconditional selflessness, “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”.

The film was made in 1959; it is black and white; and while the acting is slightly mannered, it is not too distracting. Set against the backdrop of Japan in the years surrounding WWII, it follows Kaji, a young idealist, as his idealism is tested, and worn away by the brutal realities of life.

The plot runs something like this: Kaji is at first given dispensation from the war, so that he can take up the role of mine supervisor. It so happens that the mine uses Chinese prisoners for its labour, and Kaji finds himself sympathising with them. Kaji quickly learns though, that his ideals are not shared—indeed he finds himself hated by all parties—his superiors, his workmates, and even the prisoners, who see him as smug and self-serving.

There is then an uprising by the prisoners and suspicion is subsequently directed against Kaji. As punishment he is drafted into the army—which is where No Greater Love ends.

That then is an outline of the plot. So to the real question—does No Greater Love succeed as a depiction of the human condition?

The Australian biologist Jeremy Griffith, whose work focuses on explaining the human condition, suggests that humans are born with unconditionally selfless instincts—the type of love described by Christ, and referred to in the film’s title. However, when consciousness arose, we found ourselves at odds with those instincts: “When our intellect began to exert itself and experiment in the management of life from a basis of understanding” says Griffith, “in effect challenging the role of the already established instinctual self, a battle unavoidably broke out between the instinctive self and the newer conscious self” [ www.humancondition.com/book-of-answers-what-is-love/].

As a result of this battle, “the intellect was left having to endure a psychologically distressed, upset condition, with no choice but to defy that opposition from the instincts”. This defiance took the form of anger, alienation and egocentricity—characteristics inimical to ideality, and which constitute what we recognize as ‘reality’.

The human condition has been having to live under the implication that we are bad for this defiance, when in fact we are not; and the human journey has been a journey undertaken in the hope and faith that we would one day find sufficient knowledge to exonerate ourselves. It was this hope that kept us going despite all the self-corruption we suffered, both individually, and as a species.

Kobayashi’s film succeeds as an allegory for our condition not just because it is a recognition of the fate of idealism in the world, but above and beyond that, because Kanji’s obdurate, stubborn refusal to stop—his determination to keep going, despite the horrors that he has to undergo—represents our belief that humanity is essentially good, despite all appearances, and that one day we would gain the knowledge needed to liberate ourselves from insecurity—if only we just keep going. Kobayashi’s film resonates mightily in this context.

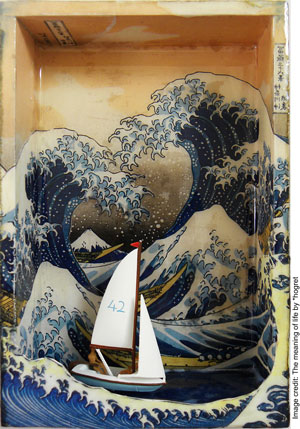

The poster chosen for the movie gives a great insight into Kobayashi’s view of the human condition, and the underlying theme of the movie, showing in silhouette a line of soldiers marching up a steep slope. In spirit it closely resembles the famous picture by Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave Off Kanagawa, showing fishing boats plowing forward through terrifying and remorseless waves. It is worth noting that Under the Wave Off Kanagawa is also a picture used by Griffith to illustrate humanity’s courage in continuing to search for knowledge despite the self-corruption it brings. Perhaps the Japanese ethos contains a particular recognition that stoicism is required in the face of the human condition.

In the end, Kobayashi’s triumph is that he has created an allegory that reminds us of the real journey—humanity’s journey—the one that we are all involved in. True, it is not a comfortable reminder—this takes discipline to endure—it is perhaps entertainment for a samurai—but the reward is an honest depiction of our condition, one that reminds us of our heroism. And there is immense pathos in that.

Please wait while the comments load...

Comments