Another World

I recently watched what I would call a semi auto-biographical TV documentary on SBS called Beyond the Dreamtime. The program was based on the life and work of the artist and photographer Ainslie Roberts (d. 1993) who was born in London in 1911 but emigrated to Australia with his family in 1923. Roberts is best known for his paintings depicting the stories and myths of the Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime which he published in many books. These are a couple I particularly like.

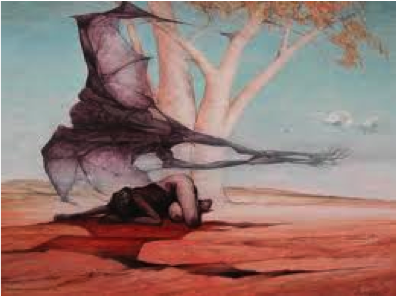

Koolulla and the Two Sisters

Narahdarn and the Forbidden Tree

Narahdarn and the Forbidden TreeReflecting on my thought processes while watching the program, I see that my mind is busily applying Jeremy Griffith’s explanation of the human condition found in his various publications, most recently FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition. Applying his all-encompassing framework of understanding allows me to decipher and access the ‘truths’ embedded in Roberts’ commentary, images and paintings. Without this explanation I know I would have had no real inclination and certainly no ability to access the underlying substance and meaning in the subject matter. In contrast, with the benefit of Jeremy’s explanation, I can process the commentary and draw out the underlying story in a way that is so intuitively and logically accountable. Moreover, the experience that flows from this ability is deeply rewarding and nourishing. In essence, the explanation is allowing me to connect to the fact there is another world, a world beyond our human condition which buries so many of the most fundamental and wonderful truths about ourselves, our world and our true meaning and place within it. To try and give you an idea of what I mean.

The narration of Beyond the Dreamtime begins, ‘All religions are an attempt to reach me…I am the Great Mother, the mother of all wisdom. I am the life force and all life. I dwell in your dreams…the first beings have kept the Earth since the first day waiting to be heard but the roar of cities has deafened me’. Taken literally these concepts can sound pretty abstract but at the same time you have a sense that something deeper is being alluded to. So who is the ‘me’ being personified here? Using Jeremy’s explanation I can understand the ‘me’ as being, at base, a fundamental law of thermodynamics called Negative Entropy. Jeremy terms this law ‘Integrative Meaning’. He explains that, in an open system, such as Earth, where energy is derived from an outside source, the sun, that energy causes matter to continually develop into larger, more ordered and stable wholes. Jeremy explains in first principles how for humans, this integrative force, through physics, chemistry and biology, has ultimately manifested in our all-loving, cooperative instinctive self, our soul, our intuition, our conscience (To read more about Integrative Meaning go to www.humancondition.com/freedom-​obvious-truth-of-the-​development-of-order-of-matter). Hence the ‘me’ is the cooperative, loving, integrative aspect of ourselves that religions ‘attempt to reach’, that bubbles up in our dreams and that is deafened by the alienating ‘roar of cities’.

The program outlines that Roberts was a successful businessman in advertising but then had a nervous breakdown in mid life. Roberts says he would ‘read a newspaper and be physically sick’. He goes on to say that he would clamp his hands over his ears and that he wanted to ‘fall back into mum’s womb’. This is powerful imagery of how daunting and depressing our human condition really is when we face it. Roberts’ denial was obviously breaking down causing him to honestly see what Jeremy calls the ‘upset’ of the human condition, which is the agony we live with of being unable to truthfully explain our contradictory nature.

In 1950 Roberts was sent to Alice Springs by his family and friends on a one-way ticket and told, ‘go up to Alice and cure yourself’. He describes being in Central Australia as a ‘form of therapy’, that you can ‘drink the air like champagne’. He travelled to Central Australia again in his later life and says, ‘I feel as though I have come home which is a wonderful feeling, to feel a part of it is an enormous thrill’, and ‘the feeling of this country releases you from the cities’. The narration adds ‘you are not alone, you belong to the great design from which we have emerged’. I can understand the language and imagery as alluding to the powerful emotional and therapeutic effect of breaking away from the alienating noise of the city and reconnecting with what Jeremy terms the original instinctive aspect of ourselves: our soul.

Following his first visit to Central Australia in 1952, Roberts met and became a close friend of ethnologist, photographer and later, anthropologist Charles Pearcy Mountford (d. 1976). Over the next four years he spent extended periods of time with Mountford and the Aboriginal people in remote areas of Central Australia. In the early 1960’s Roberts began to capture the Aboriginal Dreamtime on canvas. He says; ‘When we recognise the ancient self, the creative self leaps forward’ and that he ‘felt like [he] had been born again’. What is being acknowledged here is that nature resurrects the repressed soulful, creative, imaginative aspect of ourselves. Roberts says, ‘the normal person thinking of the Dreamtime might be deluded to look at cities and Aboriginal problems but underneath this is a deep consciousness that most people are not aware of’. This is acknowledgement of our denial of a deeper reality.

The narration of the ‘Great Mother’ goes on: ‘To discover me within you can be terrifying’, and then Roberts says, ‘the Olgas [an iconic rock formation in Central Australia] are full of feelings and reverberations, not all of which are pleasant’. He then recounts the experience of painting on his own late at night away from his camp in a remote location. He describes a feeling of ‘not being alone and all of a sudden [having] had an overwhelming sense of panic and a need to get back to camp and leave all this behind’. He says that the next day he realised that he had ‘stumbled into the spiritual world’ and the experience was a ‘turning point for [him] ’. This can all sound a bit spooky, but maybe it is not. Through Jeremy’s insights I can understand that the reason that these places drenched in nature bring up feelings for us that are ‘not pleasant’ is that if we are quiet and contemplative with all the noise of our alienated world stripped away, we start to feel—without conscious awareness—this integrative force at work on Earth, and the manifestation of that in ourselves as our soul, which contrasts with how apparently at odds we are with that cooperative force. That process produces uncomfortable feelings because it brings us into direct contact with our less-than-ideal human condition.

Roberts says that the ‘Dreamtime world of aboriginal Australia is the foundation of the Aboriginal’s reality…The land and the Aborigine are one…They consider that every natural feature, every rock, every tree are part of them…It is the source of their sensitivity…Dreamtime is an ongoing sacred reality [and] ongoing source of spiritual energy that is available to them’. What is that all about? Without the benefit of Jeremy’s insights I would have had a superficial and generally diminishing view of the Dreamtime as a bunch of abstract, imaginative stories of how man, animals and the land were created. Now I get a small sense of how extraordinarily sensitive and connected aboriginal races were to the land and surrounds in their natural state. Jeremy often refers to the following quote from pre-eminent philosopher Laurens van der Post about the Bushman of the African Kalahari: ‘He [the Bushman] and his needs were committed to the nature of Africa and the swing of its wide seasons as a fish to the sea. He and they all participated so deeply of one another’s being that the experience could almost be called mystical. For instance, he seemed to know what it actually felt like to be an elephant, a lion, an antelope, a steenbuck, a lizard, a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree, yellow-crested cobra, or starry-eyed amaryllis, to mention only a few of the brilliant multitudes through which he so nimbly moved’ (The Lost World of the Kalahari, 1958, p.21 of 253). It is amazing to contemplate that this is not an exaggeration. I can see how special and tangible a vehicle the Dreamtime stories were to the Aboriginal people, maintaining their connection to the real world. I can also understand that the Aboriginal Dreamtime was a form of metaphysics, of communicating fundamental truths using stories and metaphors in the absence of first principle knowledge. Jeremy’s framework of understanding now makes it safe and possible for these truths to be translated from metaphysic to knowledge. You might think the specialness could be lost in translation but I suggest you will experience the complete opposite.

Overall, watching this program with Jeremy’s insights as a backdrop, I get a glimpse of the fact that there is another world, the real world, and that what I and nearly all of us live in day-to-day is a false world. We think we live in the real world but it is not real, and this other ‘real world’ is not make-believe, it is actually very real! As Jeremy explains, because of the human condition we have necessarily had to block out this real world—nature, our soul, the child within—until now. Jeremy sets out that with the accumulation of knowledge, principally through science, he has been able to synthesise the biological explanation of the human condition and only this can bring an end to our separation from this world. In this way Jeremy’s insights are a vehicle to re-access the ‘real world’, and with it gain a sense of profound meaning, a sense of the wonder and beauty of this world. This is not in some mystical, metaphysical or superficial, feel-good way but in a deeply authentic way.

If I follow my logical train of thought and accept that there is a real world that is full of the magic that we had access to as children, then I can see that Jeremy’s description of the trauma for children and adolescents of seeing the human condition within themselves, leading to a psychological turning point he terms ‘Resignation’, of having to ‘turn away’, live in denial of the real world is deadly accurate. How hard must we have wanted to hang onto that real world and not sell it out? Thinking about it gives you a measure of the moral conflict and deep depression that ultimately resulted in us resigning. For one moment, I look deeply into Jeremy saying that adults (me) are like aliens to children and know that he is not exaggerating one bit, because in truth, we are living in parallel universes. As Jeremy explains, having no choice but to resign we adopt a false, deluded, competitive, selfish, and superficial frame of reference. We ultimately embrace the false world. Similarly, we are in a parallel universe to those rare individuals like Jeremy who, due to their circumstances, didn’t have to resign and so maintained access to the real world and with it a capacity to think free of denial and so delve into the human condition which is off limits for pretty much everyone else.

Similarly, if I accept there is a real world that we are totally divorced from then I also start to get a glimpse of the agony of more innocent races (that are still relatively connected to that world) such as the Australian Aborigine encountering more upset races such as ours. This thought quickly becomes a springboard for knowing that Jeremy’s explanation of the human condition is the only thing that will bring about a sincere and meaningful reconciliation between the various races of mankind.

Moving on in my reflection, I smile and think, what Jeremy is saying is the truth, he has solved the human condition no less, and how amazing is that! All this brings into focus for me the kernel of what is so amazing about Jeremy’s explanation and what struck me some 20 years ago on first reading his second book Beyond The Human Condition. He explains that humans have been fundamentally good despite appearing bad, that we are variously upset but all equally good. He doesn’t simply draw out the dichotomy of the human condition or label our upset as bad or evil, he goes to the heart of what has caused our upset, and through compassionately and logically explaining the cause, allows our condition to be ameliorated. How awesome is it going to be to resurrect the real world now that we can understand the human condition and for future generations of kids to never have to die inside, to never have to leave that real world now with the benefit of these understandings. That is so good.

Please wait while the comments load...

Comments