Four Radio Interviews with Jeremy Griffith from the many he gave during the 2003 launch of his Australasian bestselling book A Species In Denial

(View other reviews, interviews and responses to A Species In Denial here)

Qantas Interview

In this excellent brief introductory overview of Jeremy Griffith’s work, Olympian Lisa Forrest interviews Jeremy on her Qantas Inflight Radio program ‘A Current of Air’. It was broadcast in January 2004 in all Qantas domestic and international flights to a potential audience of 1.2 million passengers.

Transcript (with minor edits)

Lisa Forrest: You’re with Lisa Forrest on Radio Q. Australian biologist and writer Jeremy Griffith has spent almost 30 years studying the human condition. A Director of the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood [now called the World Transformation Movement] and the author of three books including the recently released A Species In Denial, Jeremy’s work centres on the belief that humans’ capacity for good and evil is the result of two factions within everybody. The gene based instinctive part of us struggling with the conscious self. Jeremy joins us on A Current of Air to tell us a bit more about A Species In Denial. Welcome.

Jeremy Griffith: Hello Lisa.

Lisa: I feel a little bit unfair asking you to explain 30 years of work in eight minutes but we’ll give it a go.

Jeremy: Okay.

Lisa: What exactly are we denying about ourselves?

Jeremy: Well, as you said, my latest book is called A Species In Denial, and it is called that because there is this underlying issue of good and evil in the human make-up that humans have found it easier to just not look at. When humans look into themselves there is a dark side they have never been able to make sense of. There is this deeper issue about us humans. We have a capacity for both so-called ‘good and evil’—a capacity for love and kindness but also a capacity for extreme insensitivity, selfishness and brutality. It is this underlying deeper issue of the biological reason for good and evil in the human make-up, which is the issue of the human condition, that my book addresses and explains. It gets to the heart of the matter of what it is to be human.

Lisa: I’m going to just ask you this because in my understanding though we know that we have the capacity for good and evil and we always have, isn’t that why there are laws in place. Even in religion there is the requirement to ‘treat others as you would treat yourself’, that sort of idea. So we’ve understood it but we’ve denied it and that’s why we’re in trouble now. Is that what you’re saying?

Jeremy: We’re aware of the existence of good and evil but I’m suggesting that subconsciously we once, when we were young, tried to grapple with this issue and decided it was too depressing a subject to go near. We looked into ourselves and saw these elements of greed, anger and indifference, and unable to reconcile the ideality with the reality we found the issue so depressing that we learnt to block it out of our minds, basically live in denial of it.

Lisa: Right.

Jeremy: We do take comfort from religion. Religions do look after that deeper, troubled insecure aspect of the human make-up, but ultimately we’re conscious beings and need to understand ourselves. Religions teach us that God loves us for example, but ultimately we need to understand why He does, why we humans are capable of the incredible atrocities that go on. I’m a biologist and this is a question of behaviour, of human behaviour, so ultimately this is a question for biologists. Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson recently said that ‘the human condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences’ and so it is. The issue of the human condition is the realm of inquiry where science and religion finally overlap, which is why is it such a contentious realm to go into. Nevertheless finding understanding of ourselves is the Holy Grail, the ultimate objective of the whole human journey I suggest.

Lisa: So by understanding this about ourselves, by understanding the human condition and setting ourselves free of this guilt, how will that manifest itself on a day to day basis?

Jeremy: It takes time for this understanding to filter right through your whole being. I mean, I’m opening up Pandora’s box. What this is all about is the deepest darkest secret in human life. There has been this forbidden room, a room that humans have been too afraid of to enter because of the self-confrontation involved. In truth we’ve been capable of studying everything but ourselves and the result of this avoidance or denial is that the world of humans has become extremely escapist, artificial and superficial. The way out of our predicament lay in the opposite direction, lay in going back through the layers of denial and alienation to this core issue and solve it. This is what my book does, it goes back through all the layers of alienation to the core problem of the human condition, the issue of our corrupted, ‘fallen’ state, and explains that state, and by so doing ends the underlying insecurity in the human make-up. It lifts the burden of guilt as you said from humanity. The human condition was this great forbidden subject that was always there that we could never go too near for fear of encountering fearful self-confrontation and depression, but now we can go there safely. We can understand ourselves through biological reconciliation of these two warring factions within ourselves and the result of this reconciliation is that all expressions of that war, namely our anger, alienation and egocentricity, will subside—and a new variety of people will appear on Earth, free of the underlying insecurity of the human condition.

Lisa: I’m speaking to Jeremy Griffith and we’re talking about his book A Species In Denial. How long will it take for this to filter through then? How long before we see new human beings emerge?

Jeremy: This war between our already established instinctive self and our newer conscious self emerged some 2 million years ago with the emergence of fully conscious, big brained humans. Instincts orientate a species but don’t allow it to understand how to behave, so necessarily when we became conscious we had to defy our instinct, but the only way we could do this, since we couldn’t explain ourselves, was to try and block out the implied criticism from our instinctive self, try to attack it and to try to prove it wrong. We unavoidably became alienated, angry and egocentric. So this is a dignifying understanding, it says that we are good and not bad after all. And as you absorb this wonderful fact that humans aren’t fundamentally evil, all the upset angers, egocentricities and alienations subside.

Lisa: One of the things that worries me about this argument when I think about it, say in terms of racism where people will say: ‘Well I’m racist, I’m going to be comfortable with this, and so it doesn’t matter that I treat someone badly because they are a different colour or whatever it is, that it’s just human nature and that’s just me.’ I know you’re not saying it’s okay, you’re not condoning violence and aggression and all those sorts of things, but aren’t you saying that by releasing ourselves from that guilt, we’re not actually trying to be any better than that.

Jeremy: People do think at first that being able to biologically explain why we became upset will legitimise upset, corrupt behaviour, but it actually doesn’t. What happens is that through understanding it you ameliorate or heal the upset. Understanding is compassion, it subsides the upset. While we couldn’t defend ourselves we couldn’t afford to admit that we were corrupted without condemning ourselves. The human condition was a very paradoxical situation. As Ludwig Wittgenstein put it ‘About that which we cannot speak, we must remain silent’. We couldn’t discuss the situation without inevitably condemning ourselves, or condemning those that were more upset than others. All we could do was impose equality which was artificial because really there are differences between the genders, between races and between individuals. The whole Pandora’s box unravels from first being able to explain the human condition, defend humans, because then, and only then, is it safe to finally admit all these differences—because you can do it without criticising those who are upset, those more embattled by the human condition—because we can finally explain the unavoidable reason for why we became embattled.

Lisa: Right, so it’s not about actually condoning it as you say, it’s about actually saying yes that’s how we are, this is what we can do about it.

Jeremy: Yes it is about dignifying humans. ‘Honesty is therapy’ and we can now be honest. We couldn’t go around saying I’m a corrupted human or I’ve lost my innocence, because that would have just led to people saying well you’re bad you should go and shoot yourself. But now that we can understand the human condition and explain the good reason for why we became corrupted we can afford to be honest. The saying ‘honesty is therapy’ is all very well but we have not been able to be honest until now. Carl Jung emphasised that ‘wholeness depends on being able to own our shadow’, but as a species we have never been able to own our shadow, we’ve never been able to explain the dark side of human nature—but now at last we can. This is the breakthrough of breakthroughs the whole human journey has been working towards. Science makes a clarification of the human situation possible by explaining the different ways the gene-based and nerve-based systems process information, one is insightful and one isn’t, and an unavoidable battle developed.

Lisa: Jeremy, that’s only a tiny part of what the book goes into and I thank you very much for trying to explain it to us today.

Jeremy: Thank you very much Lisa for the opportunity.

Lisa: I’ve been speaking to Jeremy Griffith, and his book is called A Species In Denial.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

‘Drivetime’ 2SM Interview

Focusing on the relationship between religion and science, Gareth McCray interviews Jeremy Griffith on his Sydney ‘Drivetime’ 2SM Radio program on 4 June 2003. It was relayed to 30 other stations across New South Wales and Queensland.

Transcript (with minor edits)

Gareth McCray: I want to talk a little about science, about science and religion, and to some extent about philosophy—and try and put it at a level that maybe even I can understand. There is a special launch tomorrow of a marvellous book called A Species In Denial. The book deals head on with the human condition and its affliction upon humanity. The author, Jeremy Griffith, is an Australian biologist and also a director of the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood. Jeremy will be one of the speakers at the launch of this book tomorrow, Thursday the 5th of June, at 12.30 in the Australian Museum. One of the other speakers, in fact I had an interview with him last week, is another great Australian, Tim Macartney-Snape. They’ll be addressing the critical need in society to scrutinise and debate new ideas. Now A Species In Denial represents to some extent, I’m quoting Tim Macartney-Snape, ‘a definitive treatment of the subject of the human condition, humans’ capacity for good and evil. It boldly explores this new frontier and introduces the reader to the immense potential that this exploration brings.’ Mankind has always explored bold new vistas, including our own. I’m very pleased to say that Jeremy joins me on the line, good evening Jeremy.

Jeremy Griffith: Good evening Gareth.

Gareth: Thank you very much for your time. Could I pose a question? Humanity has evolved step by step by step. Is it possible we have reached a point in our evolution where technology has gone faster ahead than humankind’s ability to deal with that technology? Are we out of sync?

Jeremy: Yes, there is a marvellous quote by US General Omar Bradley that, ‘The world has achieved brilliance without conscience, ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants’, and I think that pretty well sums it up. There is an entire dimension to the human situation that we haven’t been able to grapple with, and that is this area of the human condition. Technology has entirely outstripped the internal journey, the need to inquire into ourselves. We happily explore outer space but not inner space.

Gareth: I once had a debate, an argument or discussion with a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney, and I don’t want to name him, or get into a discussion about technology but my argument was that man is still really in the cave while our technology is out there in the 21st century.

Jeremy: Yes, I fully agree. My book is called A Species In Denial because there is this all-important subject that humans have lived in almost complete denial of. I mean Darwin related humans to animals, and that was nerve racking enough for humans. In fact Darwin left unaddressed the issue of humans, only referring to them once in his book The Origin of Species I think, outside of references to humans practising selection of animals for breeding purposes. He left unaddressed the whole issue of why humans behave the way they do. Humans are competitive, aggressive and selfish when the ideals are the complete opposite of being cooperative, loving and selfless, and we’ve never been able to explain why.

Gareth: Yes.

Jeremy: Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson said recently that ‘The Human Condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences’, and so it is, but it is an extremely difficult subject to open up because we’ve had to live in denial of the issue of the human condition —and the reason we have had to is because the issue of the human condition has been such a confronting and depressing subject for humans. We haven’t been able to look at ourselves, at least not honestly.

Gareth: Could I ask on behalf of my friends who are listening, none of us scientists. You are a biologist, what then is your audience for this book?

Jeremy: Everyone really. It’s not written in highbrow, academic language. The only difficulty is the subject matter. The human condition is such a confronting and thus difficult subject to raise for humans that you can’t in fact raise it unless you are able to raise it completely, deal with it thoroughly. By that I mean you have to be able to explain the human condition, bring compassionate understanding to the human situation, or you must leave the subject alone. If you take people out into the minefield of the issue of self you have to be able to take them safely right across the minefield, or you must not venture out there. When you can take them right across in safety, as my book does, it amounts to introducing a whole new paradigm for humanity and that means introducing a lot of new information. Basically every aspect of human life comes under review. I mean the human condition is the underlying issue in all human affairs and so all aspects of human life come under review, which is why it’s quite a big book.

Gareth: 526 pages

Jeremy: Is it? [laughter]

Gareth: The question I want to ask, and I haven’t fully read the book, although I have every intention of doing so, is this. On one side we have religion, on the other side we have science. Is it possible to suggest that religion has part of the answer and that science has part of the answer, and that what humanity now needs to do is open the door between the two of them to see the truth.

Jeremy: Yes, if you like, religions have been the custodians of the ideals of life while science has been responsible for inquiry into the reality of our non-ideal human state. Religion and science are both looking at humans, albeit from two different viewpoints, therefore they ultimately must be able to be reconciled. For instance, religions teach us that God loves us but ultimately, being conscious beings, we needed to understand why we were lovable, where the dark side in the human makeup, our potential for incredible brutality etc, comes from. There had to be a reconciling biological understanding. Science doesn’t even have an interpretation for words like love or soul or spirit or God for that matter. We needed a reconciliation between the spiritual and the material, between ideality and reality, between faith and knowledge, religion and science.

Gareth: But religion does offer answers for many people.

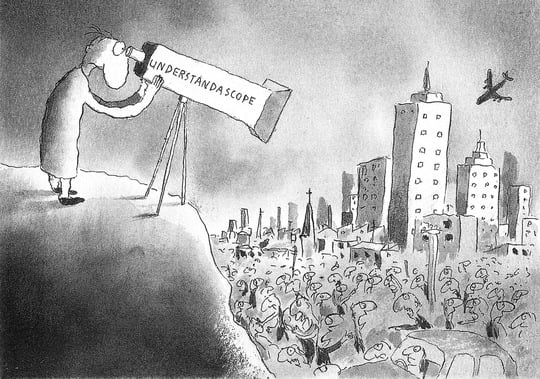

Jeremy: I agree that all the great truths are fully present in religious texts but those truths are presented in abstract, metaphysical terms. There had to come a time when those truths would be able to be explained in first principle scientific terms, a time when rational understanding and explanation would be able to demystify religious metaphysical descriptions, dogma and mysticism. The unravelling point of the entire mystery of the human situation is the issue of the human condition, the issue of our contradictory natures, why are we the way we are. Self-knowledge has been the holy grail of the whole human journey. The cartoonist Michael Leunig once drew a cartoon of a person standing on a hill overlooking an immense city and he’s peering through this telescope at the city below him and written on the side of the telescope is the word ‘Understandascope’. That pretty well sums the situation up, we’ve never been able to make sense of ourselves and our world, we have needed an understandascope, and that is what my book presents, an understandascope for the human condition.

Gareth: Let me ask you, when we make sense of ourselves through reading your book how will things be different to what they are now?

Jeremy: Well, within all humans there exists these expressions of the human condition, our capacity for greed, insensitivity, indifference, and even brutality, a dark side in human nature that we’ve never previously been able to make sense of. In religious terms we’ve never been able to explain the origin of sin. Unable to understand ourselves we have coped by blocking out the whole issue of self, living in denial of the issue of the human condition. Instead we have preoccupied ourselves with distraction and escape from the issue of self. As a result of this escapism we have become an alienated, fraudulent, immensely superficial and artificial species. With the ability to understand ourselves the situation completely changes. Understanding is compassion, it gives us the ability to go back and dismantle all the block-out, evasion, denial and alienation. The human race can enter therapy on mass. Instead of becoming sicker we enter rehabilitation now that we can understand ourselves, understand where all the upset in the human make-up was coming from.

Gareth: Yes OK, OK. So this book is going to be available as of now, is it?

Jeremy: Yes, it’s in the book shops now.

Gareth: It’s called A Species In Denial, it’s been written by Jeremy Griffith, a highly qualified Australian biologist. It certainly has the support of people like Tim Macartney-Snape, who is another great Australian. Tim is the first Australian to climb Mount Everest, and he has climbed it twice, both without the support of bottled oxygen, and there are also other eminent Australians who are very supportive of this book. A Species In Denial will be launched tomorrow if you want to investigate the issues of good versus evil, science and religion and understanding us. It’s certainly a book you should go out and get. Jeremy, just as a last comment, there is a very famous poet by the name of Gerard Manley Hopkins, who I know you’ll be familiar with, and he wrote a poem in which he said ‘The world is charged with the grandeur of God and it will shine out like shook foil’, which to me seems to combine both of the things you’re talking about, of science on one hand and religion on the other.

Jeremy: Yes, when we can demystify God, at last confront God, having been insecure in the presence of God or the ideals, we will ‘shine’, be liberated from our human condition, liberated from our insecure, afflicted, immensely alienated state. Humans are currently so alienated from all the truths and beauty in the world that they are effectively asleep. As the poet Shelley wrote, ‘Our boat is asleep on Serchio’s stream, its sails are folded like thoughts in a dream’. Well we have the reconciling understanding that will allow us to wake up now and we will discover a world more beautiful than we have dared to dream of.

Gareth: Jeremy, congratulations on the book, I’d love more time to talk to you sometime.

Jeremy: Thanks very much Gareth.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Darwin Radio 104.1 Interview

Focusing on the crux issue of the origin of the dark side of human nature and Jeremy’s Adam Stork explanation of it, this 10-minute interview between Daryl Manzie and Jeremy Griffith aired on Darwin Radio 104.1 TOP FM on 6 October 2003. It was part of the ‘Territory Talk’ segment, which is broadcast across the Northern Territory.

Transcript (with minor edits)

Daryl Manzie: Have you ever wondered, have you ever sat back at times and thought about the evil that man can perform against man. You don’t have to look very far do you to see how human beings can disregard all the moral laws that we consider are important for living in a civilised state and do some dreadful things. Look at the Second World War, look what happened to Jewish people, the final solution, and the people involved were considered in the late 1920s as being at the top of the pyramid in terms of civilisation—music, the arts, medicine. It doesn’t take much for all of us to slip off that pedestal and do some dreadful things to our fellow man. There has been a book written by a biologist Jeremy Griffith and in it he says humankind cannot come to terms with the issue of good and evil and therefore we chose to turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to our human condition. To talk about his book we are joined by Jeremy Griffith. Good morning to you Jeremy.

Jeremy Griffith: Good morning Daryl.

Daryl: Now it is something that when we do occasionally have a spare minute, and there’s not much of them around nowadays, you do tend to think what is the difference between our pleasant lives and our moral stance on issues and the fact that history shows that mankind has been so cruel to his fellow man.

Jeremy: Yes, my book is titled A Species In Denial because there is this underlying issue in all human affairs of good and evil in the human makeup that humans have found easier to just not look at. My book starts with the analogy of there being an elephant in our living rooms that we don’t recognise, this ‘elephant’ being this all-important question of the human condition. When we look into ourselves, as you intimated, there is this dark side we’ve never been able to make sense of. Every time we look inside ourselves, or into the state of the world with all the drug abuse, family breakdown, depression, loneliness, inequality, terrorism there is, underlying it all this deeper issue of humans themselves, human nature, why are we the way we are, and unable to answer that we just learn to dismiss it as, ‘look it’s just human nature and that’s unchangeable’. But really until we could find the greater dignifying, ameliorating, reconciling, uplifting understanding of ourselves, make sense of the dark side of ourselves, our problems were only going to keep piling up.

Daryl: I mean we do it in different ways. We look to religion to try and understand these problems, we teach our children that you’ve got to do the right thing by everyone, we try and live under a set of rules we impose which look at fair play and punishment for those that break the rules, but when it comes to crunch time we are all the same and history shows that no matter how well your society is managed it doesn’t take much for us to turn around utterly and completely and do some terrible evil things.

Jeremy: That’s right, we are aware that we have this capacity for incredible insensitivity and brutality but when we try and explain it, and I’m a biologist and ultimately it’s a biological question ‘why evil?’, we have no answer. You are right, religions tell us that God loves us and we take comfort from that, but ultimately, being conscious animals, we needed to understand why we are lovable. Where does this dark side come from? The ultimate objective of science was one day to be able to throw light on the human condition. Harvard’s leading biologist Edward O. Wilson recently said that ‘the human condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences’, and so it is. It is also the realm where religion and science, faith and reason, finally overlap. Finding understanding of the human condition is the holy grail of the whole human journey. In Jungian terms wholeness depends on being able to embrace our shadow, make sense of ourselves.

Daryl: Is it worth worrying about? I mean we are in denial as you say in the book but is that a good thing? I mean maybe we just forget about it and just continue to have a good time. I mean we are different to the animals, in fact animals don’t tend to prey on their own kind for fun or amusement in a senseless way whereas humans do, that’s probably the big difference between us.

Jeremy: Well, we have used the excuse that ‘animals are red in tooth and claw and tear each other’s throats out and that’s why we are’ but animals are driven by their biology of having to compete for food, territory and a mate. Humans are subject to a psychosis—the human condition is a psychosis—our angry, brutal, aggressive condition is a psychologically derived state and the question is how did this psychological state of upset and the products of it of our anger, egocentricity and alienation emerge? There is this psychological dimension that is unique to humans and that’s what my book deals with, it explains the origin of that psychosis.

My book explains that humans were once like other animals, controlled by our instincts and then we became conscious beings and needed to understand our world. The problem was as soon as we began to experiment in understanding our already established instinctive self was in effect intolerant of this need to search for knowledge. I use the analogy in my book of a migrating bird that is perfectly instinctively orientated to its migratory flight path.

Were you to place a conscious brain on the head of that bird and jump in an ultralight and follow its migration, what would you see happen? The bird would fly along its migratory path and start thinking for itself for the first time. It thinks ‘well I think I’ll fly down to that island and have a feed on those apples, why not’. There’s no reasons, no understandings available at this stage. In fact he is only going to find the understandings by persevering with this search for knowledge, defying his instinctive self. So this bird has to fly off course and carry out his experiments in self-adjustment but immediately he does this his instincts say ‘you’ve got to come back onto the flight path’. At that moment the equivalent of the human condition emerges. The bird is in a diabolical dilemma. It must carry on the responsibility of being a conscious being and persevere with its search for knowledge despite the resistance from its instinctive self. Tragically, unable to sit down and explain to its ignorant instinctive self that there was a good reason for its defiance of the instincts, all that bird could do was block-out the unjust criticism coming from its instincts, try to prove the criticism wrong and retaliate against the unjust criticism. The bird that became conscious becomes angry, egocentric and alienated.

But if you look at that simple little story who is the hero of the story? The hero is the bird that had the courage to persevere with the search for knowledge despite being misunderstood as bad by its instinctive self and becoming corrupted as a result. Now if you think about that little story obviously the day that that bird can explain itself, explain that there was a biological reason it became so corrupted, then finally the upset corrupted state can subside. Had that bird been able to understand itself it would never have become angry towards its instinctive self and the criticisms emanating from it or tried to block those criticisms out or try to prove them wrong, it would never have become angry, alienated and egocentric. So-called ‘sin’ would never have emerged. It follows that the day it can finally explain itself then it has the means to stop being angry, alienated and egocentric. So human nature is not some immutable, unchangeable state rather it’s the product of a psychosis and when we finally can explain and understand that psychosis the psychosis goes. Self-understanding is the real path to freedom and peace on Earth.

Daryl: Yes, well Jeremy it is certainly a very, very involved subject. I suppose the other part of our human nature is we do think about these sort of issues and that’s part of being human. The book itself, A Species In Denial, is certainly receiving excellent reviews. I’ve got a copy of it here and I’m definitely going to read it because it’s one that I think would interest anyone that wants more knowledge about why we are, who we are, how we are. I thank you for talking with us this morning.

Jeremy: Thanks for the opportunity Daryl.

Daryl: Good on you. That’s Jeremy Griffith and he is the author of a book called A Species In Denial, it’s out and it’s available and it’s certainly something that covers a very, very interesting subject. Why are we like we are and why do we do terrible things to one another. It’s part of our condition isn’t it.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

2SM Radio Interview

Focusing on the relationship between men and women, this interview between Di Coveny Garland and Jeremy Griffith aired on 2SM Radio on 14 October 2003. 2SM is a Sydney radio station that syndicates its programs, including this program, to a number of regional stations across New South Wales, including 2AD Armidale, 2LM Lismore, 2MG Mudgee, 2MO Gunnedah, Radio 97 Tweed Heads, 2NZ Inverell, 2PK Parkes, 2RE Taree, and 2TM Tamworth, as well as 4GY Gympie in Queensland.

Transcript (with minor edits)

Di: On the line we have Jeremy Griffith, author and someone who’s very interested in the human condition. Good evening, welcome to the program.

Jeremy: Good evening Di.

Di: So tell me the human condition, when you say those words what do you mean?

Jeremy: Well with all the problems in the world of youth drug abuse, obesity and suicide, family breakdown, epidemic depression, inequality and terrorism, there’s a common denominator, and much deeper issue, and that’s humans themselves. Our human nature, our capacity for love and kindness on one hand but also extreme insensitivity and brutality on the other, and it’s this underlying question of good and evil in the human makeup that is the issue of the human condition. That’s what my book addresses.

Di: Now you’ve also looked at a lack of understanding between men and women and I think if you go back hundreds and hundreds of years or look at today, even though we are so advanced as a society there are still problems there.

Jeremy: Yes and there is a philosophical problem. We tend to try and solve problems of reality by dogmatically imposing idealism, or correctness, on the situation. In this case in the form of equality between the sexes, imposing a gender neutral world. But I suggest that’s an avoidance and a denial of the real differences that exist between sexes, not only in the physical differences but also in the different roles men and women have played in the struggle of the human condition.

Di: So are you saying that you don’t believe in equality?

Jeremy: I do believe in equality, but not by dogmatically imposing idealism on the problem. That is a denial of reality. It doesn’t solve the underlying problem. It’s a band-aid solution that avoids the deeper issue of why there is this schism between the genders, between races and even between different age groups and generations. We need to look deeper and find the dignifying, liberating understanding of the differences. Bring the parties together through understanding rather than by imposing dogma. Dogma is the opposite of knowledge. Indeed it’s the enemy of knowledge because it denies reality, it prohibits questioning. We need to confront and understand the human condition, not deny it.

Di: So have you come up with any options for how we could do it better?

Jeremy: Well, I suggest this issue of the human condition has been with us since time immemorial, since the emergence of consciousness in fact. When we look into the dark side of ourselves and at these dilemmas and dichotomies in life, we’ve never been able to understand and reconcile those issues and warring factions and so we have lived an immensely superficial and artificial life of just not confronting the issues. My book’s titled A Species In Denial because we’ve had to deny this underlying issue of the human condition as unconfrontable. We have just dismissed it as, ‘well that’s just human nature and it’s unchangeable’, but in fact it is a biological question that has to be answered. I’m a biologist. Harvard biologist Edward Wilson said recently that ‘the human condition is the most important frontier of the natural sciences’ and so it is. We’ve got used to not addressing this deeper, core issue of the human condition but it nevertheless exists and the time has come when band-aid solutions are no longer adequate. We need the deeper understanding of ourselves, the compassionate insight that makes us not need dogmatic artificial denials and forms of management and other superficial, escapist ways of living. We need to get real, get to the bottom of things and bring forward a dignifying understanding of humans, and that’s what my book does.

Di: That’s all very interesting. Well Jeremy lovely to talk to you tonight. Congratulations on your book.

Jeremy: Thank you Di.

Di: That’s Jeremy Griffith, author of A Species In Denial.