Banjo Paterson: why is the Australian bush poet so revered?

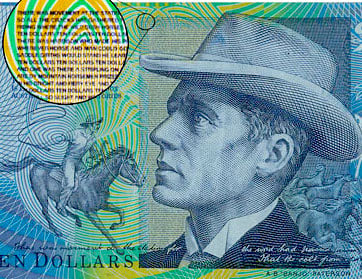

Banjo Paterson is Australia’s most famous poet; he is held in such high regard that his face, and the words of his most famous poem, The Man from Snowy River, appear on the Australian $10 note.

Biologist Jeremy Griffith explains that the reason that Banjo (his real name was Andrew Barton Paterson) is so revered is because of the prophetic nature of his work. Through his poetry Banjo alluded to the importance of Australia’s role in the human journey as being due to Australia being the youngest and most fresh of nations. More particularly, Banjo alluded to the role that that innocence has to play in the battle to find understanding of human nature, which in fact is the understanding the human race needs to liberate itself from the bondage of the human condition.

Jeremy Griffith says:

“The human condition is the agonising, underlying, core, real question in all of human life, of are humans good or are we possibly the terrible mistake that all the evidence seems to unequivocally indicate we might be? While it’s undeniable that humans are capable of great love, we also have an unspeakable history of brutality, rape, torture, murder and war. Despite all our marvelous accomplishments, we humans have been the most ferocious and destructive force that has ever lived on Earth–and the eternal question has been ‘why?’ Even in our everyday behaviour, why have we humans been so competitive, selfish and aggressive when clearly the ideals of life are to be the complete opposite, namely cooperative, selfless and loving? In fact, why are we so ruthlessly competitive, selfish and brutal that human life has become all but unbearable and we have nearly destroyed our own planet?!”

This prophetic element in Banjo’s poetry is particularly clear in Song of the Future, and the aforementioned The Man from Snowy River.

‘And it may be’ wrote Banjo in Song of the Future, when referring to Australia’s role in the journey to understand the human condition, ‘that we who live in this new land apart, beyond the hard old world grown fierce and fond and bound by precedent and bond, may read the riddle right [of are humans good or are we possibly the terrible mistake that all the evidence seems to unequivocally indicate we might be] and give new hope to those who dimly see, that all things may be yet for good and teach the world at length to be one vast united brotherhood’.

In The Man from Snowy River Banjo Paterson makes it clear that it is because of its relative innocence that Australia is important, and even more particularly, that it will fall to an innocent to ‘read the riddle [of the human condition] right’. As in the biblical allegory of David and Goliath, The Man from Snowy River tells a story of a boy doing what men cannot. It tells the story of a thoroughbred colt that has escaped and joined the wild brumbies (horses) living in the Snowy Mountains of Australia. A hunt is organised with all the best riders of the country to try and recapture him. When they gather, among the seasoned veterans is a boy: ‘And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast’, writes Banjo Paterson.

So small and young did he look that old Harrison, the owner of the escaped thoroughbred colt, tries to stop him riding with them, saying he wouldn’t be up to the chase; but in his wisdom, Clancy of the Overflow spoke up for the boy, saying, ‘I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end’.

As it turns out, when the mob of brumbies escape the pursuing riders by galloping down a steep and dangerous mountain side, it is only the boy who can follow them; and then while all the other riders watch in awe, he chases them up the other side ‘Till they halted cowed and beaten, then he turned their heads for home’.

Jeremy Griffith explains that the deeper meaning in Banjo Paterson’s The Man from Snowy River—the meaning that resonates so strongly that Australia has included the whole poem on the $10 note—has to do with the human condition, and our inability to deal with it, once we suffered from it. The human condition has been such a ‘riddle’, such a ‘terrible descent’, that we couldn’t even really admit that it existed without first having the defense of WHY we humans are angry and selfish, and not selfless and loving. It follows then, that the only person able to provide this explanation had to be someone not suffering from the human condition, someone outside or innocent of it—in fact, a boy. This is the source of the truth that we recognise in The Man from Snowy River. The boy goes where the men can’t go to retrieve the truth about the human condition that has alluded the human race; metaphorically bring back the escaped thoroughbred, slay the monster Goliath that no one else can go near.

Most wonderfully, biology is now able to provide the full explanation of our angry and selfish behaviour. This comprehensive explanation of the human condition is available in this Introductory Video Series and Part 3 of Freedom: Expanded Book 1, by Jeremy Griffith.

With the explanation of the human condition now available, we are able to see that we are suffering from an upset state, characterised by angry, alienated and egocentric behaviour that is the result of a two million year old, unavoidable clash between our gene-based instincts and our emerging nerve-based consciousness.

Thankfully, our upset can now subside because we have the compassionate, explanatory, real defence for our angry, selfish behaviour—‘the riddle has been read right’, the truth has been retrieved from its unapproachable position. The implications for humanity, as Banjo prophesised, could not be more exciting—it changes things profoundly—all things will now be good.

The former president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, Professor Harry Prosen, recognises the thrilling breakthrough that Griffith’s explanation represents, saying, ‘I have no doubt this biological explanation of Jeremy Griffith’s of the human condition is the holy grail of insight we have sought for the psychological rehabilitation of the human race.’

The Man from Snowy River by Banjo Paterson

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses - he was worth a thousand pound,

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are,

And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight.

There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the cup,

The old man with his hair as white as snow;

But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up -

He would go wherever horse and man could go.

And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand,

No better horseman ever held the reins;

For never horse could throw him while the saddle girths would stand,

He learnt to ride while droving on the plains.

And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast,

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony - three parts thoroughbred at least -

And such as are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry - just the sort that won’t say die -

There was courage in his quick impatient tread;

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye,

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

But still so slight and weedy, one would doubt his power to stay,

And the old man said, “That horse will never do

For a long a tiring gallop - lad, you’d better stop away,

Those hills are far too rough for such as you.”

So he waited sad and wistful - only Clancy stood his friend -

“I think we ought to let him come,” he said;

“I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end,

For both his horse and he are mountain bred.

“He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko’s side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough,

Where a horse’s hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between;

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But nowhere yet such horsemen have I seen.”

So he went - they found the horses by the big mimosa clump -

They raced away towards the mountain’s brow,

And the old man gave his orders, “Boys, go at them from the jump,

No use to try for fancy riding now.

And, Clancy, you must wheel them, try and wheel them to the right.

Ride boldly, lad, and never fear the spills,

For never yet was rider that could keep the mob in sight,

If once they gain the shelter of those hills.”

So Clancy rode to wheel them - he was racing on the wing

Where the best and boldest riders take their place,

And he raced his stockhorse past them, and he made the ranges ring

With the stockwhip, as he met them face to face.

Then they halted for a moment, while he swung the dreaded lash,

But they saw their well-loved mountain full in view,

And they charged beneath the stockwhip with a sharp and sudden dash,

And off into the mountain scrub they flew.

Then fast the horsemen followed, where the gorges deep and black

Resounded to the thunder of their tread,

And the stockwhips woke the echoes, and they fiercely answered back

From cliffs and crags that beetled overhead.

And upward, ever upward, the wild horses held their way,

Where mountain ash and kurrajong grew wide;

And the old man muttered fiercely, “We may bid the mob good day,

No man can hold them down the other side.”

When they reached the mountain’s summit, even Clancy took a pull,

It well might make the boldest hold their breath,

The wild hop scrub grew thickly, and the hidden ground was full

Of wombat holes, and any slip was death.

But the man from Snowy River let the pony have his head,

And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer,

And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed,

While the others stood and watched in very fear.

He sent the flint stones flying, but the pony kept his feet,

He cleared the fallen timber in his stride,

And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat -

It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride.

Through the stringybarks and saplings, on the rough and broken ground,

Down the hillside at a racing pace he went;

And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound,

At the bottom of that terrible descent.

He was right among the horses as they climbed the further hill,

And the watchers on the mountain standing mute,

Saw him ply the stockwhip fiercely, he was right among them still,

As he raced across the clearing in pursuit.

Then they lost him for a moment, where two mountain gullies met

In the ranges, but a final glimpse reveals

On a dim and distant hillside the wild horses racing yet,

With the man from Snowy River at their heels.

And he ran them single-handed till their sides were white with foam.

He followed like a bloodhound on their track,

Till they halted cowed and beaten, then he turned their heads for home,

And alone and unassisted brought them back.

But his hardy mountain pony he could scarcely raise a trot,

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur;

But his pluck was still undaunted, and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.

And down by Kosciusko, where the pine-clad ridges raise

Their torn and rugged battlements on high,

Where the air is clear as crystal, and the white stars fairly blaze

At midnight in the cold and frosty sky,

And where around The Overflow the reed beds sweep and sway

To the breezes, and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word today,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

Please wait while the comments load...

Comments