Since his death, a book vilifying Sir Laurens van der Post has been published. The following article by one of Sir Laurens’ close acquaintances, Christopher Booker, is a strong rebuttal of the book. The article is reproduced here with the kind permission of the British Spectator magazine, in which it appeared in October 2001.

Small lies and the greater truth

by Christopher Booker

“Storyteller: The Many Lives Of Laurens Van Der Post”

By J. D. F. Jones

John Murray, £25, pp.505, ISBN:0719555809

The key to what makes this biography of the writer Laurens van der Post so unusual is betrayed in a tiny footnote on p. 357. In a flash of vanity, J. D. F. Jones cannot resist claiming credit for an obscure review he had written of one of Sir Laurens’s autobiographical books back in 1983, in which the ‘present author’ (himself) had gone out ‘on what was then a slender limb and declared that he did not believe a word of this “flabby and embarrassing stuff”.’ What makes this so odd is that, 16 years later, after Sir Laurens’s death in 1996, Mr Jones should have pushed himself forward to become his ‘authorised biographer’, to be given access to most, but not all, of van der Post’s private papers. Without revealing his belief that van der Post was a complete fraud, he won the confidence of the author’s daughter Lucia, who had worked with him at the Financial Times. He received an advance of £50,000 from Sir Laurens’s publishers. He then set out single-mindedly to strip away every last shred of the reputation of the man whom the headline to his 1983 review had called ‘van der Posture’. It must be the only occasion in history when someone has managed to hijack the position of ‘authorised biographer’ to produce what is nothing but an utterly ruthless hatchet job.

Alarm bells began to ring when Mr Jones appeared to be making only the most perfunctory efforts to interview all those who had been closest to Sir Laurens, including his family and friends like myself. Anyone wanting the full picture would have talked at length, for instance, to Lucia herself, to Tom Bedford, Laurens’s nephew and close ally, or to Tom’s wife Jane, his longtime amanuensis. When Jones had the chance in South Africa to interview the only survivor of Laurens’s childhood, his last remaining sister, he apparently ‘arrived late, left early and spent most of the “interview” talking himself’. As for me, he gave the game away a few months back by ringing out of the blue to apologise that we hadn’t been able to fix up an interview, but he had now finished the book and it would be full of the most amazing revelations about how Laurens was ‘a liar’ in almost everything he ever said. He gleefully started to spill out some of his ‘discoveries’. ‘He was never a colonel in the army. He never had a half-Bushman nurse, Klara. And what would he have thought if he had known he was descended from a 17th-century Hottentot princess-turned-prostitute?’ I replied that I thought Laurens would have been rather pleased.

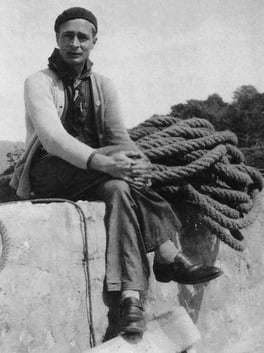

Certainly Laurens made himself vulnerable to any would-be demolition merchant, on two particular counts. First, as anyone who knew him well was soon aware, when he reminisced about the events of his life he was a tale-teller. Everything became a little larger than life. To those of us who sat entranced while he spoke of the Kalahari or African wildlife or his time as a prisoner of the Japanese in the war (which was undoubtedly the time when he ‘found himself’, after rather lost years scratching a living as a young South African expatriate in the England of the 1930s), this tendency to embroider life into ‘story’ was all part of the magic. And to prurient eyes he was perhaps even more vulnerable when it came to his somewhat chequered love life: not least the episode exposed by a Sunday tabloid the week after his death, in which he fathered an illegitimate child on a 15-year-old girl.

All this Jones has set about exploiting to the nth degree. Aided by researchers in South Africa, he has crawled over every conceivable detail of Laurens’s life, to show him up as a ‘compulsive liar’. There was no mulberry tree in the garden where Laurens claimed as a child to have sat reading the classics. The oft-quoted episode when Laurens intervened to protest at two Japanese journalists being thrown out of a café could not have happened, because ancient newspaper files revealed he was playing hockey that day for Natal. He probably embroidered the story of his surrender to the Japs in Java in 1942. He exaggerated the closeness of his relationships to Mountbatten and Jung after the war. He romanticised his famous ‘discovery’ of the Kalahari Bushmen in the 1950s (there had already been other similar expeditions). Most of the Bushman stories he recounted were not told him by Bushmen but lifted from a 19th-century collection. He exaggerated his behind-the-scenes role in the Rhodesia settlement of 1979-80 etc. As for Laurens’s romantic entanglements, their irregularity is played for all it is worth, with all the self-righteous prurience which made Jones’s book a natural candidate for lucrative serialisation in that same Sunday tabloid, along the lines of ‘we expose the secret sex life of Prince Charles’s guru’.

So relentless is this denigration that it reminds one just how easy it is to turn anyone’s life into a negative caricature if one sets out to do so. And one is soon aware that a biography conceived on these lines presents Jones with two problems. Firstly, he is so determined not to see anything positive in his subject that he goes way over the top, as for instance in his claim that van der Post pretended to be a lieutenant-colonel during the war when he was only a captain. When we finally come to the tortuous evidence for this damaging charge, it turns out he undoubtedly was made a half-colonel, even though the official record is confusing as to the date. When Laurens set up as a Cotswold dairy farmer in the Thirties, Jones tries to allege he was a hopeless farmer who saw little of his cows because he spent all his time in London trying to get work as a freelance journalist. Yet when Laurens eventually succeeded as a writer, no one expressed more surprise than someone who stayed with him in those days, because this did not fit with her memory of him as a dedicated farmer who did little more than stomp about in mud, milking cows. Even Jones includes a fellow-officer’s evidence that when, in 1940, Captain van der Post was part of a hazardous expedition to restore Haile Selassie to his throne, involving more than a thousand camels, he was infinitely more effective in looking after his camels than anyone else.

And when Jones is eager to recycle any salacious anecdote about Laurens’s love-life, however distorted or improbable, it is almost comical how much less demanding he is of the evidence for his own stories than he is for those told by the man he obsessively tries to blacken as a fantasist and a liar. As more trivial evidence of how casual Jones himself is with facts, I cannot resist citing his belief that Private Eye’s romantic fictions about Prince Charles, which regularly featured parodies of gnomic wisdom from the ‘royal guru van der Pump’, were written by Craig Brown. Mr Brown was never part of the group, including myself, which actually wrote them.

A much larger problem for Jones is that he is wholly incapable of understanding those qualities in Laurens which evoked such extraordinary response from millions of readers, such love from his wide circle of friends, and which gave him his unique position in the inner life of our age. The point about his writings on the Bushmen, like his gift for holding an audience rapt with his lectures, was not that every detail of what he said was factually true. It was that he opened up a spiritual dimension to life in our spiritless modern world like no one else. As a friend once put it, ‘Laurens was a dreamer. He lived half way between heaven and earth.’ OK, with some of the details of his own life, he turns out to have been rather more of a Walter Mitty than we had realised. But even this was somehow all of a part with his power to give a mythic dimension to life, investing everything which happened with a cosmic resonance. In all the conversations I had with him, there was scarcely one when he did not come up with an unexpected flash of illumination on what was going on in the world, even if only a comment on some new revelation about the European Union, a project he viewed with grave suspicion.

All this positive side of Laurens has passed Jones by. There are times in his joyless, pedestrian book when one feels some editorial hand intervening to suggest he is being too one-sided. Suddenly we get a few rather forced sentences conceding that Laurens did have his admirers, or that such and such a book was not wholly without merit. It is interesting that even Jones cannot hide how, in those hellish Javanese prison camps, his fellow POWs regarded Col. van der Post as a brave, resourceful and inspiring leader of men who performed wonders in sustaining morale. But when it comes to explaining why Laurens rose from being ‘just a farm boy from the Karoo’, as the book snobbishly opens, to being admired all over the world and a guide, comforter and friend to Prince Charles, Mrs Thatcher and so many others, all Jones can offer as an explanation, again and again, is that he had ‘charm’.

I suspect the potential readers of a life of van der Post would prefer rather more than this as an explanation for why he left such a mark on the world, which is why the publishers may be disappointed by the book’s sales. Certainly there are those who relish the idea of a hatchet job being done on the ‘self-styled mystic’, but one cannot see them paying to read it. Ultimately this book exposes the limitations not of van der Post, only of its author. But at least Mr Jones has served one invaluable purpose. In digging up every scrap of dirt which anyone could find to throw at Laurens, whether real or imaginary, he has cleared the decks for some other author to write that grown-up account which the ‘authorised biography’ of such a remarkable figure should have been in the first place.

© The Spectator, 20 October 2001, Christopher Booker.