Please note, links to all the Freedom Essays are included at the end of this essay. Open any essay to read, print, download, share or listen to (as an audio).

Freedom Essay 53

The ‘instinct vs intellect’ is the obvious

and real explanation of our condition,

as all these great thinkers evidence

(this is the longer, complete version of F. Essay 4)

Written by Jeremy Griffith, 2018

Before beginning I should point out that this essay is a much elaborated and longer version of Video/Freedom Essay 4, although, since Video/F. Essay 4 is constructed differently to this essay, both essays are important in their own right. You can’t read one and think you’ve learnt what the other has to offer.

I am not the first person to identify the instinct vs intellect elements of the human condition. As described in chapters 2:6 and 2:7 of my book FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition, there have been many thinkers throughout history who have recognised that the answer to our troubled human condition lay in understanding a clash that must have occurred between our already established instincts and newly emerged conscious mind. Such thinkers include Moses, Plato and Hesiod, and in more recent times, Richard Heinberg, Eugène Marais, Laurens van der Post, Nikolai Berdyaev, Erich Neumann, Paul MacLean, Arthur Koestler, Julian Jaynes, Christopher Booker, Erich Fromm, William Wordsworth, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Blake, John Milton, Robert A. Johnson and Bruce Chatwin.

I should explain that the reason all these recognitions of the key elements involved in producing the human condition are by men is because, as is explained in F. Essay 27 and more fully in chapter 8:11B of FREEDOM, women are not as responsible for, and thus as aware of, the great battle to solve the human condition as men are. It’s not a result of biased cultural conditioning, as the politically correct movement would have us believe, but a result of a role differentiation between the sexes.

Firstly, it is important to point out mechanistic science’s extremely dangerous efforts to avoid and suppress any truthful analysis of the human condition.

The many thinkers mentioned above who have recognised the instinct vs intellect elements of the human condition demonstrate how apparent, indeed obvious, these elements are when someone is prepared to think honestly and truthfully about our condition. Of course, such honest thinking hasn’t been the norm because, as is explained in Video/F. Essay 14 & F. Essay 40, as well as in chapter 2:4 of FREEDOM, the human-condition-avoiding practice of so-called ‘mechanistic’ scientists today actively avoids, and even suppresses, such honest thinking.

The leading exponent of this human-condition-avoiding, mechanistic thinking was the famous Harvard University American biologist Edward O. Wilson (1929–2021). In particular, his Multilevel Selection theory, which provides a so-called ‘explanation’ for the actual issue of the human condition itself, not only doesn’t recognise the obvious instinct vs intellect elements of the human condition, it seeks to replace them with a patently dishonest instinct vs instinct account of our condition.

As described in Video/F. Essay 14 & F. Essay 40, Wilson tried to argue that we have both selfish and selfless instincts which are sometimes in conflict. Firstly, the truth is our instinctive nature is to be unconditionally selfless and not at all selfish (see F. Essay 21 for how we acquired our altruistic moral instincts), and, secondly, it is actually obvious that it was the emergence of our self-adjusting conscious mind in the presence of our altruistic instincts that caused our psychologically upset condition.

Despite his claims, Wilson’s non-psychological, instinct vs instinct ‘explanation’ of the human condition is not concerned with trying to confront and solve the human condition at all—rather Wilson (who most inappropriately and alarmingly was described as ‘the world’s greatest scientist’ and ‘living heir to Darwin’) was desperately trying to invent a way to avoid having anything to do with what our human condition really is, namely a deeply insecure, psychologically troubled, instinct vs intellect condition.

As explained in Video/F. Essay 14 & F. Essay 40, Wilson’s Multilevel Selection theory proposes that as well as supposed competitive, ‘survival of the fittest’, ‘must-reproduce-your-own-genes’, selfish, ‘evil’ instincts, we humans also have operating at another level some cooperative, selfless ‘moral’, ‘good’ instincts derived from what has been referred to in biology—and totally discredited as a viable theory—as ‘group selection’; thus, Wilson says, ‘The dilemma of good and evil was created by multilevel selection’. The truth, as emphasised in those essays, is that Wilson’s psychosis-avoiding dismissal of the human condition as nothing more than two different instincts within us that are sometimes at odds is a total fraud, a completely biologically dishonest ‘explanation’ of human nature. In fact, it is truly sinister, representing, as it does, the final great push to have the world of human-condition-avoiding lies with all its darkness and ever-worsening psychosis take over the world—and prevent the all-precious, psychosis-addressing-and-solving, instinct vs intellect, human-race-liberating-and-transforming real explanation of the human condition from ever seeing the light of day.

FREEDOM’s psychosis-addressing-and-solving real explanation of the human condition.

In complete contrast to Wilson’s instinct vs instinct, dishonest explanation of the human condition, the fully accountable, psychosis-addressing-and-solving, real instinct vs intellect explanation of the human condition that is presented in THE Interview and chapters 1 and 3 of my book FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition (and briefly summarised in Video/F. Essay 3) explains that our ’good’ and ‘evil’ conflicted, psychologically troubled lives are the result of an underlying battle between our original instinctive self and our newer conscious self. Basically, instincts, which are derived from the gene-based natural selection process, only give species orientations to the world, which means that when the nerve-based, fully conscious mind emerged that can make sense of cause and effect, it had to set out in search of understanding of the world to operate effectively. The problem was that this search for understanding by us fully conscious humans left us unjustly criticised by our instincts for acting independently of them, for, in effect, defying them, and until we could understand why we had to defy our instincts, all we could do was retaliate against their criticism, try to prove it wrong, and block it out; i.e., we became psychologically upset angry, egocentric and alienated sufferers of the human condition.

I might mention again what was pointed out in F. Essay 24 about why it is a ‘psychologically upset’ state. As is explained in chapter 3 of FREEDOM, our species’ particular instinctive orientation, which our conscious mind’s experiments in understanding were in effect defying, was our cooperative and loving moral instinctive self or ‘psyche’ or ‘soul’, the voice or expression of which is our ‘conscience’. Yes, our ‘conscience’ is defined as our ‘moral sense of right and wrong’, and our ‘soul’ as the ‘moral and emotional part of man’, and as the ‘animating or essential part’ of us (Concise Oxford Dictionary), while the Penguin Dictionary of Psychology’s entry for ‘psyche’ reads: ‘The oldest and most general use of this term is by the early Greeks, who envisioned the psyche as the soul or the very essence of life.’ Indeed, as the ‘early Greek’ philosopher Plato wrote about our integrative or ‘Godly’ (see F. Essay 23 for the explanation of Integrative Meaning and its personification as ‘God’), ideal-behaviour-expecting, instinctive moral nature, we humans have ‘knowledge, both before and at the moment of birth…of all absolute standards…[of] beauty, goodness, uprightness, holiness…our souls exist before our birth…[our] soul resembles the divine’ (Phaedo, c.360 BC; 65-80). So, when our conscious self became upset by our particular cooperative and loving instinctive self, or psyche, or soul, and as a result, retaliated against it by attacking it, trying to prove it wrong, and denying it, our conscious self was ‘psychologically upset’; it was instinct-offended. In fact, since ‘osis’ means ‘abnormal state or condition’ (Dictionary.com), we developed a ‘psychosis’ or ‘soul-illness’, and a ‘neurosis’ or neuron or nerve or ‘intellect-illness’. Our original gene-based, instinctive ‘essence of life’ soul or PSYCHE became repressed by our intellect for its unjust condemnation of our intellect, and, for its part, our nerve or NEURON-based intellect became preoccupied denying any implication that it is bad. We became psychotic and neurotic. (see paragraphs 63, 258 & 379-382 of FREEDOM)

Most importantly, it was only this clarifying explanation of the nature of the conflict between our instincts and our conscious intellect that gives us the redeeming ability to explain why our conscious mind had to defy our instincts, and, by so doing, reveal that we—in the sense of ‘we’ being our fully conscious, thinking self—are good and not bad after all, which ends the criticism from our instinctive self and brings reconciling and transforming peace to our conflicted and divided selves or nature or condition.

So, while the following thinkers didn’t present the actual clarifying, redeeming, reconciling and rehabilitating explanation of the nature of the struggle between our instincts and intellect, they do powerfully evidence that the instinct vs intellect explanation contains the real elements involved in producing our human condition—and, by so doing, they also expose E.O. Wilson’s supposed instinct vs instinct ‘explanation’ as the dangerously dishonest excuse it is.

I should explain that, as mentioned in F. Essay 24, and as described in paragraph 259 of FREEDOM, all that is needed to produce a psychologically upset state in a species is for it to become fully conscious because that self-adjusting capability will naturally have to defy the non-insightful, intolerant, dictatorial instincts—and this particular psychosis would not involve repression of cooperative, loving instincts as occurred with us humans, just with repression of whatever instinctive orientation is present. What happens if the species’ instincts do happen to be cooperative and loving, as occurred in us, is that it creates a ‘double whammy’ effect because the upset angry and egocentric behaviour that results from defying the instincts, is then at odds with those moral instincts, which greatly compounds the amount of guilt and upset—hence our species’ extremely psychologically upset condition. This particular ‘double whammy’ effect from having moral instincts is described in chapter 3:5 of FREEDOM. What this all means is that while not all the thinkers I’m about to mention have acknowledged that we have cooperative and loving, moral, double-whammy-producing instincts, they have all recognised the primary cause of the human condition of the conflict between a self-adjusting conscious mind and our dictatorial instincts.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

What follows are the truthful recognitions of the instinct vs intellect elements involved in the human condition from some of history’s most truthful, profound and effective thinkers.

Before presenting all these recognitions of the instinct vs intellect elements involved in the human condition, it needs to be emphasised that until the discovery by science of the natural selection process and of the replicating DNA molecule that made it possible, and of how nerves can store memories which, much developed, gives them the ability to understand cause and effect and thus become conscious or aware of the nature of change (see par. 61 of FREEDOM), it wasn’t possible to explain that our angry, egocentric and alienated human condition is not a sinful, evil state but an immensely heroic condition. Without the ability to explain this difference between instinctive orientations and conscious understandings, any thinking about the angry, egocentric and alienated corruption of our species’ original all-loving and all-sensitive instinctive self or soul could only conclude that the corruption was not something good but a bad or evil or sinful state. As emphasised in paragraphs 296-297 of FREEDOM, science therefore is the liberator of humanity from ignorance about our fundamental worth, goodness and dignity as a species.

Further, not being able to explain that our species’ so-called ‘fall from grace’ from a state of original innocence to our present extremely corrupted, angry, egocentric and alienated human condition, meant that acknowledging that our species did once live in a cooperative and loving state became increasingly unbearable as we became more and more corrupted—which is why, as we will see, the most forthright acknowledgements of our lost state of innocence come from ancient mythologies and their texts.

As evidenced by E.O. Wilson’s extremely evasive and totally dishonest dismissal of the human condition as nothing more than some selfish instincts supposedly at odds with some selfless instincts in us, this practice of denying the truth of our species’ innocent origins and present conscious-mind-induced psychologically corrupted condition is now shamelessly unrestrained. And that’s the great danger of denial; while it protects us from confronting exposure of our psychologically corrupted condition, it also prevents us from thinking truthfully and thus effectively about that condition. The danger of the art of denial, which E.O. Wilson turned into a no-holds-barred obscenely dishonest industry, is that it blocks access to our species’ freedom from the human condition through the finding of the truthful understanding of it—and now that it is found, from acknowledging that it has been found! When lying becomes unbridled, and even grossly eulogised, then extinction for the human race is only a tiny step away!

FIRSTLY, the thinkers and recordists from ancient history who have not only recognised the basic instinct vs intellect elements involved in producing the human condition, they have also recognised that we have cooperative and loving moral instincts

To begin with, it should be pointed out that the extraordinary consistency of the descriptions that are going to be given by early thinkers and recordists of how our distant ancestors did once live in a pre-conscious and pre-human-condition-afflicted, innocent, peaceful, cooperative, selfless and unconditionally loving state are borne out by the wonderful investigations and honest admissions of the American author Richard Heinberg. He found that every human culture has a myth involving both the emergence of consciousness and a ‘fall’ from an original ‘Golden Age’ of togetherness and peace, summarising in the second edition (1990) of his book Memories & Visions of Paradise that ‘Every religion begins with the recognition that human consciousness has been separated from the divine Source, that a former sense of oneness…has been lost…everywhere in religion and myth there is an acknowledgment that we have departed from an original…innocence and can return to it only through the resolution of some profound inner discord…the cause of the Fall is described variously as disobedience, as the eating of a forbidden fruit [from the tree of knowledge], and as spiritual amnesia [forgetting, blocking out, alienation/psychosis]’ (pp.81-82 of 282). Yes, as the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev recognised, ‘The memory of a lost paradise, of a Golden Age, is very deep in man’ (The Destiny of Man, 1931; tr. N. Duddington, 1960, p.36 of 310). So when John Milton titled his epic 1667 poem ‘Paradise Lost’, he was, as I’ll describe later, recognising the existence of this ‘deep’ ‘memory’ ‘in man’—as were the Australian Aborigines with their ‘memory’ of a ‘Dreamtime’.

While dishonest, denial-complying intellectualism holds sway everywhere in academic thought today,

with the best proponents of such outrageously dishonest thinking celebritised, the ancient Hebrews

collected only the words of their honest, denial-free thinking prophets. Humanity doesn’t have

any records of the academics or politicians or lawyers or artists from the 4,000-year-history of

the Israelites; instead what we have is the collection of the words of the few great prophets,

such as Moses (depicted on the left by Michelangelo (1513–15), with the horns symbolising

that he was able to talk with God; i.e., sound enough to face the truth of Integrative Meaning

and thus think truthfully and effectively), who appeared amongst them during those millennia.

That fabulous and incredibly precious collection is the Bible.

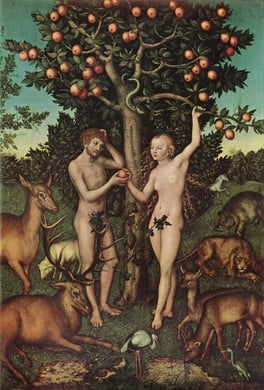

The story of the Garden of Eden in the book of Genesis in the Bible, which was written by the great Hebrew prophet Moses some 3,500 years ago, presents the best known recognition from mythology of our species’ time in innocence and of its corruption when we became conscious. In the Garden of Eden story we are told that we humans were ‘created…in the image of God’ (Gen. 1:27); in other words, we were once perfectly orientated to the cooperative, selfless, loving, integrative, ‘Godly’ ideals of life (again, see F. Essay 23 for the explanation of why ‘God’ is the personification of Integrative Meaning). The Genesis story then says that Adam and Eve were ‘disobedient’ (the term widely used in descriptions of Gen. 3) and ate the ‘fruit’ (Gen. 3:3) ‘from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil’ (Gen. 2:9, 17) because it was ‘desirable for gaining wisdom’ (Gen. 3:6). In other words, we developed a conscious mind and free will. The story then says Adam and Eve (i.e., we fully conscious humans) then became perpetrators of ‘sin’ (Gen. 4:7) and were regarded as ‘evil’ (Gen. 3:22), and as a result were ‘banished…from the Garden of Eden’ (Gen. 3:23) of our species’ original Edenic state of innocence (the dictionary definition of ‘Edenic’ being ‘the first home of Adam and Eve…a state of innocence, bliss, or ultimate happiness’ (The Free Dictionary)). So the story recognised that our ‘fallen’ (derived from the title of Gen. 3, ‘The Fall of Man’), corrupted angry, egocentric and alienated, psychologically upset, human-condition-stricken state developed, which then, through ‘gaining wisdom’, had to be understood in order for us to become ‘like God, knowing good and evil’ (Gen. 3:3), a state of psychologically relieving and rehabilitating understanding that has now arrived and is presented in FREEDOM.

In short, our Godly, Integrative-Meaning-orientated original instinctive self or soul or psyche became corrupted when we humans became fully conscious and went in search of understanding.

We can see here that while Moses’s account of the origins of the human condition recognise the elements of an original instinctive orientation which then came into conflict with a conscious mind, he wasn’t able to explain why the conflict occurred. As was emphasised, living in a time when there was no scientific understanding of the gene and nerve-based learning systems, it wasn’t possible for Moses to explain why our angry, egocentric and alienated state wasn’t an evil and sinful departure from our original cooperative and loving state.

It should be mentioned that in addition to Moses’s account of Adam and Eve’s innocent time in the Garden of Eden, the Bible also contains a passage in Ecclesiastes that reads, ‘God made mankind upright [uncorrupted], but men have gone in search of many schemes [conscious understandings]’ (7:29), and there are references Christ made to a time when God ‘loved [us] before the creation of the [‘upset’, ‘fallen’, corrupted] world’ (John 17:24), and a time of ‘the glory…before the [corrupted] world began’ (John 17:5). In the Bible the prophet Isaiah also recognised how upset/corrupted from our original innocent ‘righteous’, ‘joy[ful]’ state we humans have become, writing that ‘From the sole of your foot to the top of your head there is no soundness—only wounds and welts and open sore…Your country is desolate…the faithful city has become a harlot! She once was full of justice; righteousness used to dwell in her’, and ‘the world languishes and withers…The earth is defiled by its people; they have disobeyed the laws [become divisively rather than integratively behaved]…In the streets…all joy turns to gloom, all gaiety is banished from the earth’, and ‘This people’s heart has become calloused [alienated]; they hardly hear with their ears, and they have closed their eyes [hence the problem of the ‘deaf effect’ described in Video/F. Essay 11]’ (Isa. 1, 24 & 6:10 footnote).

Taoist scripture also features a description of our distant forebears as being ‘the Men of Perfect Virtue’ (Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines, 1987, p.227 of 325), while Zen Buddhism similarly speaks of the loss of an uncontaminated, pure state as a result of the intervening conscious mind, referring to ‘the affective contamination (klesha)’ or ‘the interference of the conscious mind predominated by intellection (vijñāna)’ (D.J. Suzuki, Erich Fromm, Richard Demartino, Zen Buddhism & Psychoanalysis, 1960, p.20).

Ancient Greek mythology also describes how humans once lived in a state of original innocence before it was corrupted by the emergence of our conscious mind. These myths, most notably recorded around 700 BC by Hesiod in his poems Works and Days and Theogony, described our species’ time of innocence: ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind / Nor e’er decrepit age misshaped their frame…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…Dying they sank in sleep, nor seemed to die / Theirs was each good; the life-sustaining soil / Yielded its copious fruits, unbribed by toil / They with abundant goods ’midst quiet lands / All willing shared the gathering of their hands’ (The Remains of Hesiod the Ascræan, tr. C. A. Elton, pp.17-18). Hesiod also recounted how this ‘Golden Age’ came to an end, telling how Prometheus stole fire—which, as I’ll explain shortly, represents consciousness—from his fellow Gods and gave it to humans for their use, an act which enraged the Gods, and Zeus in particular, who retaliated by ‘send[ing] evil for thy stealthy [theft of] fire’ (ibid. p.12). Zeus punished Prometheus by having him strapped to the top of a mountain where, every day in perpetuity, ‘down he sent from high / his eagle hovering on expanded wings / she gorged his liver’ (ibid. p.158). And humanity he punished by creating the infamous woman Pandora, who opened a great ‘box’ containing a multitude of ‘ills’ so that ‘woes innumerous roam’d the breathing world / with ills the land is rife, with ills the sea / Diseases haunt our frail humanity’ (ibid. p.16). Zeus’s punishment for Prometheus’s theft of fire brought an end to the ‘Golden Age’; where previously ‘From evil free and labour’s galling load / …[there emerged a situation where] Now swift the days of manhood haste away / And misery’s pressure turns the temples gray’ (ibid. p.15). Hesiod then chronicles his five ages of man—from the just referred to ‘Golden Age’ of innocence came the ‘Silver Age’ where there was still some innocence, then the ‘Bronze Age’ where men were tough and warlike, then the civilised ‘Heroic Age’, and then finally his own age, the completely corrupt ‘Iron Age’, where ‘misery’ has compounded to the point where Hesiod cries, ‘Oh would that Nature had denied me birth / Midst this fifth race; this iron age of earth / That long before within the grave I lay / Or long hereafter could behold the day! / Corrupt the race, with toils and grief opprest / Nor day nor night can yield a pause of rest / …Speeds the swift ruin which but slow began’ (ibid. pp.23-24). In light of what has been revealed, we can now understand that in this story fire is the metaphor for the conscious intellect (as it is in many mythologies; indeed, ‘Prometheus’ literally means ‘forethought’), and that the consequences of humans gaining a conscious mind were ‘woes innumerous’ and ‘misery’ and ‘evil’, which explains why Prometheus was punished by the Gods—in their eyes his gift to humans of consciousness was responsible for the ‘corrupt[ion]’ of the human race, for our falling out with the Godly ideals.

So, the elements of an original instinctive orientation which then came into conflict with a conscious mind were all in these myths from the dawn of civilisation, but of course, like Moses, Hesiod wasn’t able to explain WHY the conflict occurred.

But interestingly, just as Moses recognised that one day, through ‘gaining wisdom’, the human condition would be understood, and we would become ‘like God, knowing good and evil’ (Bible, Gen. 3:3), Hesiod also foretold the arrival of liberating understanding of the human condition. He records how humanity, in the form of the hero Hercules, would one day, after many labours, kill the eagle and free Prometheus and bring about reconciliation with ‘God’, i.e. with our ideally behaved instinctive self. Hesiod wrote: ‘But her [the eagle] the fair Alcmena’s hardy son [Hercules] / Slew; from Prometheus drove the cruel plague / And freed him from his pangs. Olympian Jove [the roman word for Zeus] / Who reigns on high, consented to the deed /…[and] made to cease / The wrath he felt before’ (The Remains of Hesiod the Ascræan, tr. C. A. Elton, p.158). Yes, the psychologically relieving and healing understanding that has now arrived and is presented in FREEDOM means our conscious mind is now redeemed for creating so much upset, and the criticism from our instincts ends.

The aforementioned author Richard Heinberg provides a wonderful summary in the first edition (1985) of his book Memories & Visions of Paradise of the recognitions in mythology of our species’ original all-loving and all-sensitive innocent time before we became fully conscious and the angry, egocentric and alienated upset state of the human condition emerged (the source of the quotes Heinberg has used can be found in his book between pages 8-14).

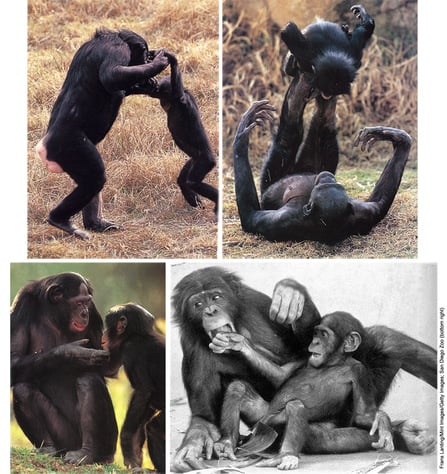

However, before presenting Heinberg’s summary, I want to mention that the nurtured loving lives of (the primate species) bonobos provide the most precious living example of how our distant ape ancestors came to live in the incredibly wonderful all-loving and all-sensitive instinctive state that the following accounts from mythology all describe. This nurtured origins of our loving moral soul that bonobos evidence is described in F. Essay 21, where the following pictures, text and quotes about bonobos appear.

The bonobo variety of chimpanzees who live south of the Congo river are the most cooperative and loving of all non-human primates, and they are also the most nurturing, as this quote evidences: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among chimpanzees, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong…Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group’ (Sue Savage-Rumbaugh & Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, 1994, p.108 of 299).

As to how cooperative, selfless and loving bonobos are, the following quotes provide powerful evidence. Firstly, from filmmakers who were producing a documentary about them: ‘they’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man [in that they share 99 percent of our genetic make-up]…Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience’ (accompanying film discussing the production of the French documentary Bonobos, 2011). And, as bonobo zoo keeper Barbara Bell said, ‘Adult bonobos demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other…For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go’ (Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998). Bonobos’ unlimited capacity for love is also apparent in this wonderful first-hand account from bonobo researcher Vanessa Woods: ‘Bonobo love is like a laser beam. They stop. They stare at you as though they have been waiting their whole lives for you to walk into their jungle. And then they love you with such helpless abandon that you love them back. You have to love them back’ (The Guardian, 1 Oct. 2015).

The consequences of this nurturing of unconditional love in bonobos is apparent in this quote: ‘bonobos historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food…and unlike chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure’ (Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, ‘Feeding ecology of the pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus)’; The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, p.271 of 435). For example, ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, Last Tribes on Earth.com, 2003; see www.wtmsources.com/143).

It should be mentioned that (as explained in F. Essay 24 and chapter 7 of FREEDOM) another consequence of our ape ancestors having been nurtured with unconditional selflessness or love is that that orientation to love liberated the development of a fully conscious mind, which this further quote from Barbara Bell evidences is emerging in bonobos: ‘They’re extremely intelligent…They understand a couple of hundred words…It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day’ and ‘They also love to tease me a lot…Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh’ (Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998).

The following then are Heinberg’s wonderful recognitions from mythology of our species’ original all-loving and all-sensitive, bonobo-like innocent time before we became fully conscious and the psychologically upset angry, egocentric and alienated state of the human condition emerged—the time, as he wrote, before ‘human consciousness’ ‘separated from the divine Source, that’ ‘former sense of oneness’, ‘an original’ ‘innocence’ that we ’can return to’ ‘only through the resolution of some profound inner discord’:

‘Virtually every culture retains a memory of a time “before the fathers fell asleep,” when there was no death or disease, when man could communicate with the animals and could ascend into heaven at will. According to the ancients the original human beings were far greater in stature than those of our time, and perfect and upright in character. In the first age war and enmity were absent, and men and women enjoyed a spontaneity of movement, thought and feeling which has since been lost. They knew an intimate communion with their Creator; indeed, God and man were one …

The most ancient written texts which survive come to us from the civilization of Sumeria, which flourished in what is now Iraq. The Sumerians spoke of a place called Dilmun, the original paradisal home of mankind, a place where death, disease and sorrow were unknown. The somewhat later texts of Babylonia and Mesopotamia say that Adapa, the first man, “was equipped with vast [denial/alienation-free] intelligence . . . His plane of wisdom was the plane of heaven.”

The Egyptians, too, believed in a time of perfection at the beginning of the world: “The divine ones created the sun. Order was established in their time and truth came forth from heaven in their days. It united itself with those who were on earth.” To the first age, writes Lenormant, the Egyptians “continually looked back with regret and envy.” …

Likewise in ancient Iran (Persia), there was memory of the “reign of Yima,” the original universal monarch who presided over an age when “there was neither heat nor cold, neither old age nor death, nor disease. . . .” And, summarizing African myths of the earliest times, folklorist Herman Baumann wrote: “In those days men knew nothing of death [they weren’t alienated and insecure and worried about their worth and meaning but felt universal and eternal, which is explained in par. 840 of FREEDOM]; they understood the language of animals and lived at peace with them; they did no work at all, they found abundant food within their reach.”

The most familiar of the paradise myths is the one preserved by the ancient Hebrews in the first two chapters of Genesis [which has already been described] … [Heinberg then mentions and comments on these words from Genesis 2] “And they were both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed.” A state of innocence, guilelessness and purity could hardly be described more succinctly, or more poignantly.

In ancient Greece, Hesiod (fl. ca. 800 B.C.) wrote of the first age, the Golden Age of Cronos. [Here Heinberg included the passage from Hesiod that was referred to earlier about ‘A golden race the immortals formed on earth’, although the translation Heinberg used of this passage is replaced there by Charles A. Elton’s more succinct translation.]

Empedocles (fl. ca. 450 B.C.) wrote [of a time when], “All were gentle and obedient to men, both animals and birds, and they glowed with kindly affection towards one another.”…In his Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C. – A.D. 17) said: “The first age was golden. In it faith and righteousness were cherished by men of their own free will without judges or laws. Penalties and fears there were none…Earth itself…gave all things freely.” Another Roman, Tacitus (A.D. 55–120), wrote: “The most ancient human beings lived with no evil desires, without guilt or crime, and therefore without penalties or compulsions. Nor was there any need of rewards…Since nothing contrary to morals was desired, nothing was forbidden through fear.” …

The Hindus of the Brahmanic period preserved the following in the Mahābharata: “The Krita Yuga was so named because there was but one religion, and all men were saintly; therefore they were not required to perform religious ceremonies. Holiness never grew less, and the people did not decrease. There were no gods in the Krita Yuga, and there were no demons…Men neither bought nor sold; there were no poor and no rich; there was no need to labor, because all that men required was obtained by the power of will; the chief virtue was the abandonment of desires…In those times, men lived as long as they chose to live, and were without any fear of Yima (the god of Death)…Being all like gods, they ascended to the sky and returned at will…Self-subdued and free from envy, they beheld the gods and the mighty prophets, and had a clear perception of all duties.”…And in the Vaya Purāna it is written: “They were characterized neither by righteousness nor unrighteousness…they moved about at will and lived in continual delight.”

Paradise myths also abound in the Americas. The Quiché Mayas, for instance, said of the first people that “…they saw instantly and they could see far…When they looked, instantly they saw all around them [they weren’t preoccupied with the human condition and having to live in Plato’s deadening dark cave of denial]”…The Hopis preserve a memory of the time when “the first people went their directions, were happy, and began to multiply. With the pristine wisdom granted them, they understood that the earth was a living entity like themselves…In their pristine wisdom they also understood their own structure and functions…The first people knew no sickness. Not until evil entered the world did persons get sick in the body or head.”

Again, in the early mythology of China we find a similar vein: “It is remarkable,” writes James Legge, “that at the commencement of Chinese history, Chinese tradition placed a period of innocence, a season when order and virtue ruled in men’s affairs.” Speaking of the perfect men of old, Kwang Tze (fl. ca. 400 B.C.) says, “In the age of perfect virtue, they attached no value to wisdom…They were upright and correct, without knowing that to be so was righteousness; they loved one another…they were honest…in their simple movements they employed the services of one another, without thinking that they were conferring or receiving any gift. Therefore their actions left no trace, and there was no record of their affairs.”’

Heinberg summarised that ‘For whatever reason, the hearts and minds of human beings became separated from the source of their own being, and shame, fear and greed appeared in consequence. Humans began to conceive of God as an imaginary separate entity’ (p.16). Yes, as pointed out earlier, and as is explained in Video/F. Essay 4 and more fully in Part 1 of the booklet Transform Your Life And Save The World, while we humans couldn’t explain the ‘reason’ for why we ‘became separated from the source of their [our] own being’, our ‘shame’ was so great we couldn’t admit that we conscious humans had destroyed paradise. Tragically, as Heinberg acknowledges in his Preface, ‘we do not want to remember’! What changes this situation where ‘we do not want to remember’ is that having found the redeeming understanding of why we lost our innocence and became corrupted, we no longer have to live in denial and can return to a non-upset, transformed life free of the human condition.

While Moses presented an extraordinarily denial-free, truthful and thus penetrating description of the nature of our conscious-mind-induced corrupted human condition in his aforementioned story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, as did Hesiod with his re-telling of the Prometheus myth, Plato, that great denial-free thinker from Greece’s peak as a civilisation, the so-called Classical Period, was even more insightful in his account of our condition. Indeed, Alfred North (A.N.) Whitehead, one of the most highly regarded philosophers of the twentieth century, described the history of philosophy (philosophy being the study of ‘the truths underlying all reality’ (Macquarie Dictionary, 3rd edn, 1998)) as being merely ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’ (Process and Reality [Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28], 1979, p.39 of 413). Well, we are now going to see just how absolutely outstanding a thinker about ‘the truths underlying all reality’ Plato was. (I should mention that all these descriptions that I’m giving here of Moses’s and Plato’s thinking are described in even more detail in chapter 2:6 of FREEDOM.)

Plato’s most famous contribution to, as Plato actually described it, ‘the enlightenment or ignorance of our human condition’ (The Republic, c.360 BC; tr. H.D.P. Lee, 1955, 514), is his description in his 360 BC dialogue of The Republic of humans imprisoned in a dark ‘cave’ (515) because they have been too afraid to face the ‘painful’ ‘light’ that would make ‘visible’ the unbearably depressing issue of ‘the imperfections of human life’ (516-517). While Plato’s cave allegory (which is described at some length in Video/F. Essay 11) perfectly described our fear of the issue of the human condition, it is Plato’s recognition of our species’ original innocent instinctive state and how it was corrupted when our conscious mind came into conflict with it that is of interest here.

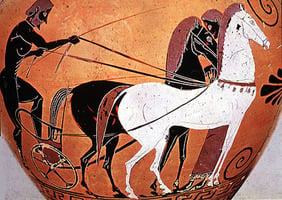

In The Republic, prior to introducing his cave allegory, Plato presented what he termed his theory of the psychological condition of humans (435). In this theory, Plato referred to a conflict between our moral instincts, which he referred to as thymos (439), and our conscious intellect, which he referred to as epithymia (439). Plato returned to this thymos vs epithymia conflict in his dialogue Phaedrus, this time describing our condition using what is, after his cave allegory, his second most famous allegory, the allegory of the two-horsed chariot.

Firstly, with regard to our species’ original innocent state, in his chariot allegory Plato gave this exceptionally honest description of it: ‘there was a time when…we beheld the beatific vision and were initiated into a mystery which may be truly called most blessed, celebrated by us in our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come, when we were admitted to the sight of apparitions innocent and simple and calm and happy, which we beheld shining in pure light, pure ourselves and not yet enshrined in that living tomb which we carry about, now that we are imprisoned in the body, like an oyster in his shell’ (Phaedrus, c.360 BC; tr. B. Jowett, 1871, 250).

And, with regard to the conflict between instinct and intellect that gave rise to our upset ‘tomb’-like human-condition-afflicted existence, Plato was equally extraordinarily insightful, writing: ‘Let the figure [of the two-horsed chariot] be composite—a pair of winged horses and a charioteer…and one of them [one of the horses] is noble and of noble breed, and the other is ignoble and of ignoble breed; and the driving of them [by the charioteer, which is us having to try to manage these two conflicting elements within us] of necessity gives a great deal of trouble to him’ (ibid. 246). Some pages later, Plato was even more explicit about the nature of the two horses and the impact of the clash between them, writing that ‘one of the horses was good and the other bad [ibid. 253] …[and this bad horse], heedless of the [charioteer]…plunges and runs away, giving all manner of trouble to his companion and the charioteer…[they being] urged on to do terrible and unlawful deeds’ (ibid. 254).

Plato added that the ‘noble’, ‘good’ horse is ‘cleanly made…his colour is white…he is a lover of honour and modesty and temperance’ (ibid. 253)—clearly the representation of what we now know is our innate, ideal-behaviour-demanding moral instinctive self, the voice of which is our conscience. Obviously Plato was not using scientific terms, but, as mentioned, he designated this white horse as thymos, which is usually translated as ‘spirit’, a concept described by the political scientist Francis Fukuyama as being ‘something like an innate human sense of justice’ (The End of History and the Last Man, 1992, p.165 of 418). And in The Republic, Plato spoke plainly about the happy, loving, goodness-and-‘justice’-expecting, soulful ‘innate’ nature of thymos (or ‘spirit’), writing that ‘You can see it in children, who are full of spirit as soon as they’re born’ (The Republic, tr. H.D.P. Lee, 1955, 441).

As for the ‘ignoble’ or ‘bad’ horse, Plato called it epithymia meaning ‘desire’ or ‘appetite’, which our erotic self (eros) is part of. Plato described this horse as ‘a crooked lumbering animal…of a dark colour…the mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf’ (Phaedrus, 253), which is clearly a reference to our psychologically upset, ‘terrible and unlawful’, ‘deaf’-to-the-truth conscious intellect.

It should be mentioned that some people have misinterpreted this ‘dark’ horse as representing animal instincts within us, specifically the instinct to reproduce, however, it is clear in the quotes above that Plato recognised our instincts as ‘innocent’ and ‘pure’, which can be seen ‘in children’, ‘before we had any experience of evils to come’, when we were ‘not yet enshrined in that living tomb which we carry about, now that we are imprisoned’. No, Plato’s epithymia with its ‘desire’ and ‘appetite’ for domination, validation and distraction, refers to the psychologically upset state of our conscious mind, which the sexual perversion of the act of procreation that is involved in sex now is part of (this perversion of sex by humans when the psychologically upset state of the human condition emerged is explained in F. Essay 27). As to why people have misrepresented Plato’s ‘dark’ horse—and indeed Moses’s Eve-tempting-Adam reference to sexual desire—as indicating we have savage, have-to-reproduce-our-genes animal instincts, it is because (as described in Video/F. Essay 14, and in paragraph 153 of FREEDOM) blaming our present competitive and aggressive behaviour on supposed savage, competitive, have-to-reproduce-our-genes animal instincts in us which our conscious mind supposedly has had to try to control, has been the main device used to deny that we once lived in a cooperative, selfless, loving innocent state that was upset by the emergence of our conscious mind.

As will be mentioned shortly when Plato’s myth of the ‘reversed cosmos’ is described, Plato—like Moses in his reference to Adam and Eve being ‘both naked’ and ‘not ashamed’ (Gen. 2)—also referred to our distant pre-conscious ancestors as having lived shamelessly in a lust-free naked, innocent state, writing that our ancestors were ‘earth-born’, meaning they were not born of the sexual perversion of the act of procreation that is involved in sex now, and there was no ‘possession of women’, no ‘devouring of one another’, and ‘they dwelt naked’.

To return to Plato’s two-horsed chariot allegory, and the explanation of the meaning of the ‘charioteer’. Designated by Plato as logos, the charioteer represents the overall situation our species has been in where we have been trying to understand the two conflicting elements within us of our ideal-behaviour-demanding instinct and our defiant, searching-for-knowledge, psychologically upset angry, egocentric and alienated intellect, with the ultimate goal being to find the reconciling understanding of our condition that will enable us to be liberated and transformed from it. Logos is normally inadequately translated as ‘reason’, but in the context of Plato’s chariot allegory it takes on a broader meaning of our reasoning intellect seeking the true understanding of our condition, or as Plato wrote, guiding our chariot to those realms of ‘justice, and temperance, and knowledge absolute’ (Phaedrus, 247), of which we have an ‘exceeding eagerness to behold’ (ibid. 248).

So, Plato’s two-horsed chariot allegory is an astonishingly clear description of the upset, ‘crooked lumbering’, ‘dark’, ‘mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf [alienated]’ intellect rising in defiant ‘heedless’ opposition to our ‘upright and cleanly made’, ‘white’, ‘lover of honour and modesty and temperance’, ‘pure’ ‘innocent’ original instinctive self, or soul, leading us to ‘terrible and unlawful deeds’, so that we are now condemned as ‘evil’ and ‘enshrined in that living tomb’ of alienated psychotic and neurotic darkness.

At this point, it has to be emphasised that, like Moses’s Garden of Eden story, the chariot allegory is only a description of the conflict that produced the upset state of our human condition, not an explanation of WHY the conflict occurred. Like Moses with his story of consciousness developing in the Garden of Eden, Plato was still only able to view our intellect as an ‘evil’, ‘bad’, ‘ignoble’ influence in our lives. Despite being the greatest of philosophers, Plato couldn’t explain the human condition. He could describe the situation perfectly but he still couldn’t deliver the clarifying, psychosis-addressing-and-relieving explanation—he couldn’t explain HOW humans could be good when we appeared to be bad. As has been explained, for that to be possible science had to be developed.

Nevertheless, Plato’s insights were absolutely remarkable, for not only did he clearly identify our original state of uncorrupted innocence and the two conflicted elements that then produced our psychologically upset, corrupted, fallen human condition in his two-horsed chariot allegory, in one of his final dialogues, The Statesman, he was even more incisive. While still not able to explain why the conflict occurred and from there explain how humans are good when we appear to be bad, in what is known as the myth of the ‘reversed cosmos’ he gave a perfectly clear description of the sequence of events that led to that conflict, even anticipating its eventual peaceful resolution!

So, just as he did with his chariot allegory, Plato began his ‘reversed cosmos’ allegory by giving a truthful description of our innocent ancestors, referring to them in this instance as the ‘earth-born’ (The Statesman, c.350 BC; tr. B. Jowett, 1871, 271), so-called because they were born of the earth rather than through ‘procreation’ (ibid). ‘Earth-born’ is presumably a metaphor for the time prior to the emergence of ‘sex’ as we upset humans practise it, where, as mentioned earlier, the act of ‘procreation’ has been corrupted and used to attack the innocence of women. (And I should mention that Plato insisted that this ‘Golden Age’ in our species’ past was a historical reality, writing that in ‘this tradition [of the earth-born man], which is now-a-days often unduly discredited, our ancestors [in the form of existing relatively innocent ‘races’ of people, such as those who still exist today like the Bushmen of the Kalahari and the Australian Aborigine], who were nearest in point of time to the end of the last period and came into being at the beginning of this [more upset period], are to us the heralds [of that earlier innocent age]’ (ibid. 271). Of course, being members of modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, the Bushmen and the Aborigines are still going to be full of upset compared to our distant, original fully innocent, bonobo-like ancestors—they are only relatively innocent compared to most ‘races’ today (see par. 860 of FREEDOM).)

What now follows is Plato’s second extremely honest description that he gave of this innocent ‘Golden Age’ in our species’ past; he wrote that we lived a ‘blessed and spontaneous life…[where] neither was there any violence, or devouring of one another, or war or quarrel among them…In those days God himself was their shepherd, and ruled over them [our original instinctive self was orientated to living in an integrative, cooperative, loving way]…Under him there were no forms of government or separate possession of women and children; for all men rose again from the earth, having no memory of the past [we lived in a pre-conscious state]. And…the earth gave them fruits in abundance, which grew on trees and shrubs unbidden, and were not planted by the hand of man. And they dwelt naked, and mostly in the open air, for the temperature of their seasons was mild; and they had no beds, but lay on soft couches of grass, which grew plentifully out of the earth’ (ibid. 271-272). [Note how what is said in this last sentence equates perfectly with the picture of bonobos sitting naked on grass that was included earlier, despite Plato having no knowledge of bonobos.]

Continuing with his extraordinary honesty and resulting clarity of thought, Plato then described how management of our lives transferred from our instincts to our emerging consciousness, and how we slowly began to accumulate knowledge: ‘Deprived of the care of God, who had possessed and tended them [we disobeyed our original instinctive orientation to living in an integrative, cooperative, loving way], they were left helpless and defenceless…And in the first ages they were still without skill or resource; the food which once grew spontaneously had failed, and as yet they knew not how to procure it, because they had never felt the pressure of necessity [we had lived in a cooperative, sharing, loving way, free of the insatiable greed that exhausts resources]…the gifts spoken of in the old tradition were [now] imparted to man by the gods [of fire, creativity, agriculture and so forth], together with so much teaching and education [knowledge] as was indispensable…fire…the arts…seeds and plants…From these is derived all that has helped to frame human life; since the care of the Gods, as I was saying, had now failed men, and they had to order their course of life for themselves, and were their own masters’ (ibid. 274).

He also described the upset, corrupted, fallen state that resulted from the emergence of consciousness, writing that in the very beginning the world was of a ‘primal nature, which was full of disorder…[then, when] the world was aided by the pilot [God, the process of integrating matter] in nurturing the animals [nurturing some animals, namely our primate forebears—this is an absolutely astonishing recognition of the nurturing process that gave us our moral instincts, a process that is described in F. Essay 21], the evil was small, and great the good which he produced [in our ‘nurtur[ed]’, innocent, all-loving bonobo-like ape ancestors], but after the separation, when the world was let go [when the conscious mind began to challenge the instincts for mastery], at first all proceeded well enough [our intellect mostly deferred to our instincts]; but, as time went on, there was more and more forgetting [alienation, or separation from our instinctive moral self], and the old discord [disorder] again held sway and burst forth in full glory [the psychologically upset, divisive, disordered state of the human condition emerged]; and at last small was the good, and great was the admixture of evil, and there was a danger of universal ruin to the world’ (ibid. 273). (Note that what Plato has said here perfectly reiterates Hesiod’s recognition that was included earlier of the deterioration of the human race through ever increasing levels of upset, which Hesiod described as progressing through five ages to eventually ending in the state where ‘Corrupt the race, with toils and grief opprest / Nor day nor night can yield a pause of rest / …Speeds the swift ruin which but slow began’.)

And showing even more honesty and clarity of thought, Plato then described how such truthful, denial-free, God/Integrative Meaning-acknowledging thinking would one day re-establish cooperative, loving order amongst humans: ‘Wherefore God, the orderer of all, in his tender care, seeing that the world was in great straits, and fearing that all might be dissolved in the storm and disappear in infinite chaos, again seated himself at the helm; and bringing back the elements which had fallen into dissolution and disorder to the motion which had prevailed under his dispensation, he set them in order and restored them, and made the world imperishable and immortal. And this is the whole tale’ (ibid. 273).

Even more astonishing still is the fact that Plato could not only think truthfully enough to see and thus prophesise how such truthful, effective thinking would one day ‘set them [humans] in order and restore…them’, he went on to predict that the restoration would be achieved by appreciating that the corrupting search for knowledge was of paramount importance. While still not able to scientifically explain why the conflict occurred and from there reveal how humans are good when we appear to be bad, Plato did recognise that we had to search for knowledge. Posing the question of whether a ‘blessed and spontaneous’, instinctively guided innocent ancestor ‘having this boundless leisure, and the power of holding intercourse, not only with men, but with brute creation [in other words, having the power to sensitively relate to each other and even to other creatures]’ would prefer that existence over the situation of an upset human, someone ‘of our own day’ who is dedicated to developing ‘a view to philosophy’ and ‘able to contribute some special experience to the store of wisdom’, Plato said that ‘the answer would be easy’—he would ‘deem the happier’ the life ‘of our own day’ in which we each had the opportunity to ‘contribute some special experience to the store of wisdom [the necessary search for knowledge]’ (ibid. 272)!

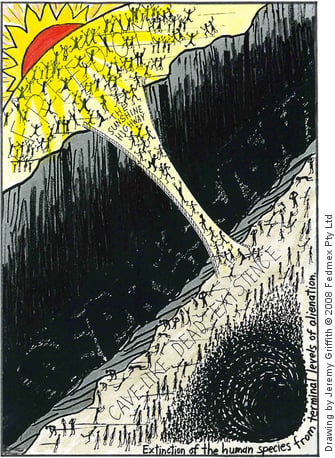

So that is Plato’s truly extraordinary, denial-free, pre-scientific account of our past instinctive ‘blessed and spontaneous life’ and the subsequent emergence of our conscious mind that allowed us to become our ‘own masters’, the result of which was the emergence of our upset, ‘evil’ condition of ‘discord’—a state we were then so ashamed of that we ‘often unduly discredit[ed]’ the truth of our ‘blessed’ past, leaving us ‘enshrined in that living tomb’ of a ‘cave’-like state of dishonest psychosis and neurosis-producing denial where there was ‘more and more forgetting’. So ‘enshrined’ in denial, in fact, that the human race has now reached, as Plato predicted, the state of terminal alienation that threatens ‘universal ruin to the world’, from which only a denial-free approach, one where ‘God’ in the form of Integrative-Meaning-acknowledging truthfulness, has ‘again seated himself at the helm’, could, as has now happened with this book, ‘set them [humans] in order and restore…them’. Plato certainly had no trouble admitting the three great truths underlying the reality of our condition—that our conscious mind caused our fall from innocence, that we suffer from a psychosis, and that our distant forebears lived cooperatively and peacefully. I think we are now able to fully appreciate why A.N. Whitehead said that all philosophy, which again is the quest for ‘the truths underlying all reality’, is merely ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’!! (Indeed, the state of terminal alienation that Plato predicted would threaten ‘universal ruin to the world’ is the subject of F. Essay 55.)

It should be noted that Plato emphasised that we would ‘often unduly discredit’ the truth of our species’ ‘innocent’, ‘blessed’, ‘upright’, ‘cleanly made’, ‘pure’, ‘noble’, ‘good’, ‘modest’, ‘honour[able]’, ‘spirit[ed]’, ‘simple and calm and happy’ past—which is part of the ‘more and more forgetting [denial]’, that, unchecked, leads to ‘universal ruin to the world’. This journey to ever increasing levels of alienation and its dishonesty is the underlying story that FREEDOM documents.

There is yet one more very impressive reference that Plato makes to our species’ original all-loving, all-sensitive, always-behaving-in-a-way-that-is-consistent-with-the-integrative-cooperative-Godly-ideals-of-life instinctive self or soul. This appears in his dialogue Phaedo where he wrote that humans have ‘knowledge, both before and at the moment of birth…of all absolute standards…[of] beauty, goodness, uprightness, holiness…our souls exist before our birth’, describing ‘the soul’ as ‘the pure and everlasting and immortal and changeless…realm of the absolute…[our] soul resembles the divine [God]’ (c.360 BC; tr. H. Tredennick, 1954, 75-80).

So Moses’s Garden of Eden, Hesiod’s story of Prometheus’s theft of fire, and Plato’s various accounts identify our conscious mind as causing ‘the fall’ from an original, cooperative, loving ‘blessed’, ‘calm and happy’ state of ‘innocence’. While in their pre-scientific times they weren’t able to explain why the conflict between our instincts and intellect occurred, they did recognise that our present ‘fallen’, corrupted, psychologically upset human condition resulted from the emergence of our unique fully conscious thinking mind.

SECONDLY, the contemporary thinkers and recordists who have recognised the basic instinct vs intellect elements involved in producing the human condition, although not all have recognised that we have cooperative and loving moral instincts

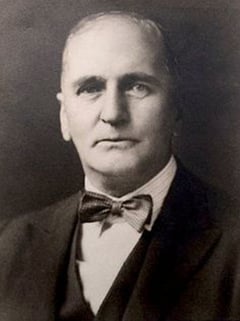

In identifying the role of instinct and intellect in producing the human condition, the South African naturalist Eugène Marais was on the right track when he recognised that ‘The great frontier between the two types of mentality is the line which separates non-primate mammals from apes and monkeys. On one side of that line behaviour is dominated by hereditary memory, and on the other by individual causal memory…The phyletic history [evolutionary development] of the primate soul can clearly be traced in the mental evolution of the human child. The highest primate, man, is born an instinctive animal. All its behaviour for a long period after birth is dominated by the instinctive mentality…it has no memory, no conception of cause and effect, no consciousness…As the new soul, the soul of the individual memory slowly emerges, the instinctive soul becomes just as slowly submerged…For a time it is almost as though there were a struggle between the two’ (The Soul of the Ape, written between 1916–1936, and published posthumously in 1969, pp.77-79). Further, Marais identified that what caused ‘the pain of consciousness’ (ibid. p.90 & 91), ‘mental gloom’ (p.92), ‘pessimism and lack of joyousness…mental misery’ (p.93)—in fact, was behind humanity’s ‘march towards the madhouse’ (My Friends the Baboons, 1939, p.9 of 124), its march towards terminal levels of alienation—was the emergence of consciousness; that it ‘is due to…some kind of suffering inseparable from the new [conscious] mind which…it [man] has acquired in the course of evolution’ (The Soul of the Ape, p.98); that ‘human consciousness [is]…the whole and only cause of this quality of psychological suffering’ (ibid. p.101). In The Soul of the White Ant, Marais also recognised that the ‘instinct…is incapable of deviation from a certain fixed way of behaving…This inherited memory is in every respect a terrible tyrant’ (1937, p.45 of 154). He further realised that ‘the so-called “subliminal soul” in man—the “subconscious” mentality—is none other than this old “animal” [instinctive] mentality which has been put out of action by the new [conscious] mentality’ (1926; published in The Road to Waterberg and other essays, 1972, p.149 of 175).

We can recognise much of the Adam Stork analogy that I use to explain the human condition (again, see THE Interview, Video/F. Essay 3 and chapters 1 and 3 of FREEDOM) in Marais’s description: of becoming conscious and, as consciousness emerged, a ‘struggle’ with the inflexible, ‘tyran[nical]’ instincts erupting. Marais not only acknowledged the elements of instincts and conscious intellect involved in the human condition, he was considering how the two elements interacted. Had he pursued and developed his insight into the emerging ‘struggle’ between the inflexible, ‘tyran[nical]’ ‘instinctive soul’ or ‘hereditary memory’ and the new ‘conscious’ ‘memory’-based, ‘cause and effect’-understanding, ‘individual causal memory’, he could have realised, as I did, that the good reason why the conscious intellect had to defy the tyrannical instincts was because the conscious mind had to search for understanding of ‘cause and effect’, and further that it was that particular guilt-producing ‘struggle’ that caused the upset competitive, aggressive and selfish, corrupted human nature. (Read more discussion of Marais’s theory.)

Much more is said in F. Essay 51 about the work of Sir Laurens van der Post, especially about his writings about the relatively innocent Bushmen people of the Kalahari Desert. What is relevant here is that Sir Laurens, who I regard as the pre-eminent philosopher of the twentieth century, and who, like Marais, was from South Africa, is his denial-free ability to acknowledge the involvement of our moral instincts and corrupting intellect in producing the upset state of the human condition. As we can see, in this passage from his 1984 book Testament to the Bushmen, Sir Laurens bravely acknowledged that ‘before the dawning of individual consciousness’ humans lived in a state of ‘togetherness’—a state that he said we have had such a hunger to return to that it has been ‘like an unappeasable homesickness at the base of the human heart’. He wrote: ‘This shrill, brittle, self-important life of today is by comparison a graveyard where the living are dead and the dead are alive and talking [through our soul] in the still, small, clear voice of a love and trust in life that we have for the moment lost…[there was a time when] All on earth and in the universe were still members and family of the early race seeking comfort and warmth through the long, cold night before the dawning of individual consciousness in a togetherness which still gnaws like an unappeasable homesickness at the base of the human heart’ (pp.127-128 of 176). In an even more explicit reference, Sir Laurens also recognised the actual ‘war’ that exists between our original innocent instinctive self and our newer conscious intellect when he wrote, ‘I spoke to you earlier on of this dark child of nature, this other primitive man within each one of us with whom we are at war in our spirit’ (The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955, p.154 of 159).

Significantly, while Sir Laurens was able to clearly recognise the ‘war’ between our original, innocent, instinctive soulful ‘child of nature’ and our newer ‘individual conscious’ intellect or ‘spirit’ he wasn’t able to provide the all-important, reconciling and redeeming reason WHY the ‘war’ occurred. As described in F. Essay 51, his great vision was the ‘hope’ that by ‘reveal[ing]’ the ‘inner life’ of the ‘child’ in ‘man’ he ‘might start the first movement towards a reconciliation’, a ‘hope’ of ‘reconciliation’ that has been achieved in my book FREEDOM.

In recognising the relative innocence of the Bushmen people of the Kalahari, Sir Laurens defiantly rebelled against the practice of denial of the truth that we humans did once live in an upset-free innocent state prior to the emergence of the human condition. (This defiance and the persecution of Sir Laurens that resulted from it is described in F. Essay 51.) For example, he wrote that ‘There was indeed a cruelly denied and neglected first child of life, a Bushman in each of us’ (The Heart of The Hunter, 1961, p.126 of 233). He even described the relatively uncorrupted harmony and sensitivity of the more innocent state of the Bushman, writing that ‘He [the Bushman] and his needs were committed to the nature of Africa and the swing of its wide seasons as a fish to the sea. He and they all participated so deeply of one another’s being that the experience could almost be called mystical. For instance, he seemed to know what it actually felt like to be an elephant, a lion, an antelope, a steenbuck, a lizard, a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree, yellow-crested cobra, or starry-eyed amaryllis, to mention only a few of the brilliant multitudes through which he so nimbly moved. Even as a child it seemed to me that his world was one without secrets between one form of being and another’ (The Lost World of the Kalahari, 1958, p.21 of 253). Note the extraordinary similarity between this description of the Bushmen, and Heinberg’s recognitions from mythology of our species’ original all-loving and all-sensitive, bonobo-like innocent time, when our ancestors were ‘equipped with vast [alienation-free] intelligence’ and ‘With the pristine wisdom granted them, they understood that the earth was a living entity like themselves’ and they ‘could communicate with’ and ‘understood the language of animals’. (Read more about Sir Laurens’s insights in F. Essay 51.)

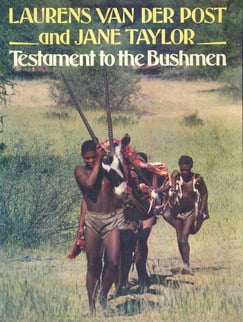

L-R: Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881)

Echoing Sir Laurens’s sentiments was the Swiss-born philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who expressed what we all do intuitively know is the truth when he wrote that ‘nothing is more gentle than man in his primitive state’ (The Origin of Inequality, 1755; The Social Contract and Discourses, tr. G. Cole, 1913, p.198 of 269) and that ‘Man is born free but is everywhere in chains’ (Le Contrat Social, 1762 [published in English as The Social Contract, 1791]). While Rousseau never used the term ‘noble savage’, these quotes show why he was associated with that concept. The English novelist and poet D.H. Lawrence also truthfully recognised our species’ lost state of sensitive innocence when he wrote that ‘In the dust, where we have buried / The silent races and their abominations [their unbearably confronting and condemning innocence] / We have buried so much of the delicate magic of life’ (‘Cypresses’, 1920).

When Sir Laurens spoke of the relatively innocent Bushmen seeming ‘to know what it actually felt like to be…a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree’, and the bonobo researcher earlier on saying the bonobos ‘love you with such helpless abandon that you love them back. You have to love them back’, I’m reminded of the great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky’s intuitive remembrance of our species’ bonobo-like time in innocence—a time when, as he wrote: ‘The grass glowed with bright and fragrant flowers. Birds were flying in flocks in the air, and perched fearlessly on my shoulders and arms and joyfully struck me with their darling, fluttering wings. And at last I saw and knew the people of this happy land. They came to me of themselves, surrounded me, kissed me. The children of the sun, the children of their sun—oh, how beautiful they were!…Their faces were radiant…in their words and voices there was a note of childlike joy…It was the earth untarnished by the Fall; on it lived people who had not sinned…They desired nothing and were at peace; they did not aspire to knowledge of life as we aspire to understand it, because their lives were full. But their knowledge was higher and deeper than ours…but I could not understand their knowledge. They showed me their trees, and I could not understand the intense love with which they looked at them; it was as though they were talking with creatures like themselves…and I am convinced that the trees understood them. They looked at all nature like that—at the animals who lived in peace with them and did not attack them, but loved them, conquered by their love…There was no quarrelling, no jealousy among them…for they all made up one family’ (The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, 1877).

The Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev who, as mentioned earlier, bravely acknowledged that ‘The memory of a lost paradise, of a Golden Age, is very deep in man’, was also approaching the truth about the actual cause of the human condition when he wrote that ‘man is an irrational, paradoxical, essentially tragic being in whom two worlds, two opposite principles, are at war’ (The Destiny of Man, 1931, p.49), and in describing these two principles, writing that, ‘The human soul is divided, an agonizing conflict between opposing elements is going on in it…the distinction between the conscious and the subconscious mind is fundamental for the new psychology’ (ibid. pp.67-68). Yes, the ‘two opposite principles’ at war in man are not, as Wilson proposed, selfish and selfless instincts within us, but our ‘conscious and the subconscious mind’. Berdyaev might as well have been thinking of Wilson when he wrote, ‘Philosophers and scientists have done very little to elucidate the problem of man’ (ibid. p.49). Again, what Berdyaev is missing is the reconciling explanation of what it actually is about ‘the distinction between the conscious and the subconscious mind’ that causes them to be in ‘agonizing conflict’. (Read more discussion of Berdyaev’s theory.)

The German psychologist Erich Neumann was another who recognised the battle and rift between humans’ already established non-understanding, ‘unconscious’, instinctual self and our newer ‘conscious’ intellectual self. In his 1949 book The Origins and History of Consciousness, Neumann wrote that ‘Whereas, originally, the opposites could function side by side without undue strain and without excluding one another, now, with the development and elaboration of the opposition between conscious and unconscious, they fly apart. That is to say, it is no longer possible for an object to be loved and hated at the same time. Ego and consciousness identify themselves in principle with one side of the opposition and leave the other in the unconscious, either preventing it from coming up at all, i.e., consciously suppressing it, or else repressing it, i.e., eliminating it from consciousness without being aware of doing so. Only deep psychological analysis can then discover the unconscious counterposition’. Yes, when we destroyed the Garden of Eden-state of original innocence we were so ashamed we ‘repress[ed]’ awareness of the existence of that original innocent state to the extent that almost everyone is now only subconsciously aware of it, with the result that for almost everyone ‘only deep psychological analysis’ can reach that awareness. Almost all humans have lived in fearful denial of the corrupted state of the human condition—and the fact of the matter is that practising such extreme dishonesty has made it impossible to think truthfully and effectively about the human condition. Only an approach that is free of denial/alienation could reach all the truths about the human condition that are being presented in these essays—and such denial-free, honest and effective thinking could only be achieved through either the ‘deep’ therapy that Neumann has referred to, or, in my case, through never having had to resign to blocking out and denying the truth of our species’ original innocent state. (Resignation to living in denial of the human condition is explained in F. Essay 30.) Thankfully, now that our corrupted state is explained and defended, denial of it, and all the dishonest thinking that flowed from it, can end!

We can see that despite Neumann’s description of the conflict between instinct and intellect the key question remains, however: why did the ‘elaboration’ of ‘the conscious’ self cause it to ‘fly apart’ from the ‘unconscious’ instinctive self? (Read more discussion of Neumann’s theory.)

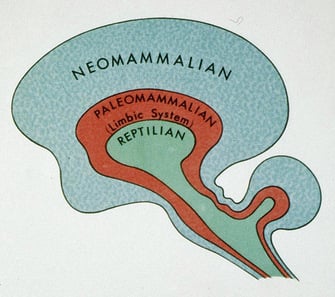

In the 1950s the American neurologist Paul MacLean developed his theory of ‘the triune brain’, which states that humans are a mentally unbalanced species because of an inadequate coordination between our emotional old brain and our cognitive new brain. MacLean proposed that humans have not one brain but three, each originating from a different stage of our evolutionary history. He said there is the inner original reptilian brain that comprises the brainstem and cerebellum, which he said tends to be rigid, compulsive and ritualistic, intent on repeating the same behaviours over and over. Then there is the middle ‘limbic’ brain, which he said comprises the amygdala, hypothalamus and hippocampus and is prominent in lower mammals and is concerned with emotions and instincts, in particular feeding, fight or flight reactions, sexual behaviour and maternal care. And, thirdly, he said there is the outer neo or cerebral cortex brain of higher mammals, which is concerned with reason, invention and abstract thought. MacLean said that ‘the three evolutionary formations might be imagined as three interconnected biological computers, with each having its own special intelligence, its own subjectivity, its own sense of time and space, and its own memory, motor, and other functions’ (The Triune Brain in Evolution, 1990). Because of the independence between these three brains MacLean saw them as frequently being dissociated and in conflict, with the lower limbic system that rules our altruistic value judgments and emotions even capable of hijacking the higher mental functions when it so chooses.

However, MacLean failed to explain what is it about the different intelligences and resulting subjectivities and senses of time and space and memories that actually causes the conflict between these two particular brains. (Read more discussion of MacLean’s theory.)

The Hungarian-born British scientist-philosopher Arthur Koestler both identified the elements of instinct and intellect involved in the human condition, and sought an explanation for how they might have produced the human condition by referring to Paul MacLean’s concept that ‘the brain explosion [in humans] gave rise to a mentally unbalanced species in which old brain and new brain, emotion and intellect, faith and reason, were at loggerheads’ (Janus: A Summing Up, 1978). As the author Bruce Chatwin [whose own contribution to this subject will be included shortly] described it, ‘At a public lecture I listened to Arthur Koestler airing his opinion that the human species was mad. He claimed that, as a result of an inadequate co-ordination between two areas of the brain—the “rational” neocortex and the “instinctual” hypothalamus—Man had somehow acquired the “unique, murderous, delusional streak” that propelled him, inevitably, to murder, to torture and to war’ (The Songlines, 1987). This recognition of humans having an old instinctive brain and a newer cognitive brain that are at ‘loggerheads’ because of ‘an inadequate co-ordination between’ the two was on the right track to explaining the human condition, answering the question that Koestler raised of how we ‘somehow acquired’ our ‘unique, murderous, delusional streak’—but again the reconciling and redeeming reason for the ‘inadequate co-ordination’ was not provided by either MacLean or Koestler. (Read more discussion of Koestler’s theory.)

The American psychologist Julian Jaynes put forward a theory of the breakdown of what he called the ‘bicameral mind’ in his 1975 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Author Rob Schultheis provides this good summary of Jaynes’s theory: ‘According to Jaynes, humankind was once possessed of a mystical, intuitive kind of consciousness, the kind we today would call “possessed”; modern consciousness as we know it simply did not exist. This prelogical mind was ruled by, and dwelled in, the right side of the brain, the side of the brain that is now subordinate. The two sides of the brain switched roles, the left becoming dominant, about three thousand years ago, according to Jaynes; he refers to the biblical passage (Genesis 3:5) in which the serpent promises Eve that “ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil”. Knowing good and evil killed the old radiantly innocent self; this old self reappears from time to time in the form of oracles, divine visitations, visions, etc.—see Muir, Lindbergh, etc.—but for the most part it is buried deep beneath the problem-solving, prosaic self of the brain’s left hemisphere. Jaynes believes that if we could integrate the two, the “god-run” self of the right hemisphere and the linear self of the left, we would be truly superior beings’ (Bone Games, 1985). Using Schultheis’s terms, Jaynes did recognise that there was a time when ‘modern consciousness’ ‘did not exist’ and humans were purely ‘intuitive’ and that later the logical, ‘conscious’ ‘brain’ usurped management from and ‘killed’ the ‘old’ ‘prelogical’, ‘radiantly innocent’, ‘god-run’ ‘intuitive’, instinctive ‘brain’. However, it wasn’t a switching of dominance from the more lateral and imaginative right side of our brain to the more sequential, logical left side of our brain that caused the upset, corrupted, alienated, sensitivity-destroying human condition, but rather the difference in the way genes and nerves process information. (Read more discussion of Jaynes’s theory.)