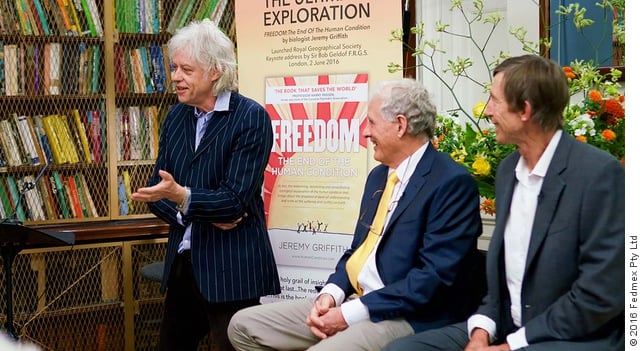

Video & Transcript of the keynote address by

Sir Bob Geldof (F.R.G.S.) at the launch of

FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition by

Jeremy Griffith at the Royal

Geographical Society, London, 2 June 2016

(To view the other presentations at the launch of FREEDOM see

www.humancondition.com/freedom-launch)

I’m here mainly because Jeremy quotes me extensively from one of my more obscure records, so thank you Jeremy for being the sole person in the world to actually purchase that record and delve into the mysteries of my genius.

The other reason why I’m here is because Jeremy takes Laurens van der Post and E.O. Wilson as benchmarks in his job as a biologist in trying to work out what’s going on. And what is going on, particularly now, is this stalling of the 21st Century that has yet to really splutter into action. We seem to be suffering some dreadful hangover from that most murderous and suicidal of centuries, the 20th century. Woody Allen puts it absolutely perfectly, in his usual mordant way, ‘More than any other time in history mankind faces a crossroads. Down one path leads despair and utter hopelessness, down the other total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.’ And I feel that more than ever, more than ever. All of us probably travel a lot. Certainly Tim [Macartney-Snape] has just arrived from Kathmandu yesterday, Jeremy [Griffith] pitched up from Australia a couple of days ago. I suppose many people here travel all the time. I’ve never felt the world more threatening, more fractious, more fissiparous, more febrile, more fucked up than it is now. And I’m 64. And there seems to be a compulsion amongst human beings that when things just get too much, too tense, then why not just engage in a bit of bloodletting.

My auntie Fi Fi was 106 at the beginning of the year and then she died. And I asked her when she was still compos mentis at the age of 103, did she feel any tensions within the Geldof household prior to the First World War; she was a little girl, but nonetheless I remembered the great tensions in Dún Laoghaire with my Dad pressed to the radio to hear the latest on the Cuban Missile Crisis and when I asked him what was up, he said ‘there may be a war’, and I said ‘when?’, he said ‘tomorrow’. And it was that close. Do I feel that now? No, not that close. But not bad, not far from there.

There’s something very amiss, and we need now to think. Humans have that great capacity, a capacity that Jeremy believes at some level bedevils us, but ultimately will be the answer to whatever it is that seems to trouble us. And right now that seems to be a question. Within the last year we have had books like Sapiens by [Yuval] Noah Harari, or Matt Ridley’s Evolution of Everything, which tries to work out what is it that led to this pass? And we’ve been at that pass before. 100, 200 years ago, one afternoon in Waterloo, we came to an end of a period of economic and political development and a new one had to begin, but only through this massive bloodletting. And in one afternoon, more boys killed than in a week of the Somme. We can’t perhaps picture it now, but it was 200 years ago. And so the 19th Century began, in 1815. One hundred years later we did have the battle of the Somme and again many millions of men and women died that week and so the 20th Century could bring itself into being and the industrial age began and thus what followed with a new polity, with a new economy, the suicide of a culture, mass dying and the hangover into the 21st Century, which we’re now suffering and which we’ll be asked to partially resolve in a couple of weeks in this country when people are asked to participate in a great new political experiment called The European Union which has kept us stable, if not at peace. And should Britain be the thread, the loose thread, that is pulled on the EU cardigan, then, believe me, my view is that sooner rather than later we will find ourselves in some sort of conflict again. Because the Balkans are still febrile, the Baltic states in terror of that revanchist thug in Russia, who is sitting there waiting for this to happen. And then that ancient pull to the south of the French, and to the east of the Germans, will begin to spark again. We mustn’t let that happen and I for one will never vote for my grandchildren even possibly going to war, never. And although the Prime Minister perhaps overstated it a couple of weeks ago, nonetheless, as Margaret Thatcher said in 1975, ‘We will see war in Europe unless we engage together.’ And in essence that is what Jeremy is coming to. If you want to reduce it to a single nub, we developed, in the early stages, self-consciousness, which is my belief, and we [Jeremy and I] argued with this over the phone the other week, is the nub of the problem. No other animal, as much as we can determine, has got self-consciousness. Once we understand ourselves and the Cartesian notion, ‘I think, therefore I am’, then you begin to unravel many of the things that animate us. But that also allows us to think. And the other ability that we developed as sapiens, as Harari points out, was empathy. And he goes into why should that have developed and Ridley goes into that even more so, and Griffith goes into it even more extensively, why did we develop this notion? In Ridley’s case, he says that was the singular item that allowed us to overwhelm the Neanderthal man, with a bigger brain. But our ability to have empathy and to think outside the individual, to act together and to imagine other worlds, that imaginative process was the thing that allowed us to breathe. Jeremy says, in effect, we’ve lost that, the imagination to understand what it is, we have to be the difference between the selfish orientated genetic animal driven thing and the nerve endings of the human brain. This is the great divide and we are completely conflicted between them. Maybe, maybe not. But we need Griffith’s, we need Ridley’s, we need Harari’s. We need as much thinking as humanly possible these days. The world has gone beyond its capacity to renew itself. Human consumption by the year 2100, that’s not far away, that’s in my grandchildren, if not my children’s lifetimes, will have increased by 1200%. We’ve reduced the idea of an economy to the single word ‘more’, more of what? Of everything.

He [Jeremy] quotes, unfortunately he quotes me, but even more unfortunately, my smaller, fatter, Irish pop star friend Bono even more extensively which negates all his arguments immediately! I quote The Eagles, everything, all the time. Seems to be where we’re at. And if all our personal circumstances are bound up in our personal happiness it’s hard not to ask of life and the planet more than it has to give. And we are at that stage. That’s not hippie stuff, that’s where we are at. We are consuming far too much stuff. ‘More’ is a euphemism for the word ‘greed’. And yet 2 billion people live on less than a dollar a day. It’s not possible ladies and gentleman to live on less than two dollars a day. It makes immense sense to rid ourselves of poverty. It rids us of war, nearly all wars are resource wars. Even Hitler had to invent Lebensraum, there wasn’t enough space for people. Echoes of that go around the European argument today. We just constantly repeat ourselves. Jeremy quotes me in one of his articles as saying that we were ensnared by the paradigm of the 20th Century which had to be competition and the resulting mayhem. Well ladies and gentlemen, this new thing that we all have in our pockets, this vital invention dreamt up by that genius British scientist in Switzerland only 25 years ago, the World Wide Web, has completely altered the economy and therefore the polity but the polity hasn’t changed so we are stuck in this limbo of change and that’s why thinkers are coming to the fore to posit new ways forward. But the thing in your pocket, the thing that he is typing into there, means a different kind of society, it means a sort of hive society where we are constantly connecting, where we are constantly touching antlers together. It must mean something completely different. What, we don’t know. But within weeks the economy was changing when the Web became commonly available. Think Gutenberg 1468. All this guy wanted to do was print a few more leaflets and make a few shillings. But within 25 years the old polity was destroyed and a new economy had come into place, literature was invented, 100 years later we had Shakespeare. He didn’t mean that! But you had the democratisation of knowledge, you had the crash of the secret societies and their coded languages of religion and law, etc. The Web is Gutenberg times six billion. Something new is going to come out of this, but what? It’s not Instagram and SnapChat and all that bullocks. It seems to me that the world is so serious Jeremy that we must engage in trivia to distract ourselves from a bleak reality. And I’m not some Jeremiad or some Cassandra, it’s just you must feel it you people here [in the audience], you must feel it? And therefore if there is new thinking, or new ideas, from a scientist, from a biologist, from a man who has used his life on almost quixotic expeditions to find Tasmanian Tigers, but to prove they live or don’t live, that they exist or they don’t exist, to prove it, to be a scientist, then you have to pay attention to a person who thinks about what a genius like van der Post has considered which influences us, and the way we live and the way we think. And the other influences around us. We are at a critical pass. 1815, 1915, 2016. It ain’t working. And we don’t need to go down the well trodden paths of the human past and our recent histories, our parents’ histories. That brilliant generation fought for freedom and then utterly bankrupt decided that they would provide a healthy, educated population fit for a newer world, a newer century. It is not up to my generation to betray that and therefore we need to think, we need new ideas, we need proselytisers, we need obsessed people, which I think Jeremy is. We need him to be questioned. We need it [FREEDOM] to be argued, we need it to be read and talked about and understood. It may be right, it may be wrong. But you need someone as committed to trying to understand what gets us here time after time. We must be better than that. We have to be better than that.

Sometimes I read a quote from a 1950s mountaineer, a Scottish mountaineer, and I’m not going to read it now but it was sent to me in the middle of Live Aid. I was scared stiff, I thought I was out of my depth, well out of my depth, I was this pop singer from Dún Laoghaire, and I was talking to Margaret Thatcher, or I would call Rupert Murdoch and Murdoch would come on the phone or whatever, and I thought ‘this is going to fail’. Daily it was failing, daily. And of course I was scared for the personal failure but that was as nothing than the failure towards those for whom we were doing it. Well it got done but I was on TV most nights urging people on. And a guy wrote to me, I was getting a lot of ‘Bob Geldof, England’ letters, most of which were very nice but I’d put in the bin. In fact, I got one from Nepal, not from Kathmandu [referring to Tim Macartney-Snape who had just arrived from Kathmandu] and it was addressed to ‘Bob Geldof, c/- Her Majesty The Queen, Buckingham Palace, London’! Because that was the only address he knew! And it came opened, ‘Sorry for opening this Sir Bob, it was addressed to you.’ It was a sweet letter, I kept that one. And the other letter I kept was from this chap who saw me and he said ‘You looked very tired last night and very scared’ and he said ‘I hope I’m wrong but I think I’m right but in a different way “I’ve been there”’. He said ‘I happened to be reading this book by this chap and there was a passage in there where we wrote about the idea of commitment, that if you do anything you commit yourself utterly to it and once that Rubicon moment has been crossed then all sorts of events happen around it to help you.’ And that is true. You know it in your own relationships, you know it in your own jobs, you know it in your life. It’s to do with that essence about, of a commitment to it. At the end of it he had this quote from Goethe, the great German poet, and Goethe says ‘Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, magic and power in it’, and that is true. And Ladies and Gentleman, in my life, never before have we needed genius, magic and power more; and the word I’d add to that is thought and thinking.

I should end there because that’s the upside isn’t it?! Fuck it! Bizarrely Jeremy wanted me to speak for an hour and he’d do 10 minutes. It was absolutely ridiculous. He wrote the book, half of it is so dense I couldn’t plough through it, so I just got the essence and I called him up and I said ‘Why am I doing an hour? You’re the scientist, you can put empiricism and study behind this idea you have.’ The people of the RGS [Royal Geographical Society], I’m proud to be a Fellow, I love this building [sniffing], it smells of intelligence and ancient-ness and books [referencing the room], excellent, I love it. And I said ‘It is the RGS, you come here to listen to the great thinkers, the great architects, the great scientists, you come here to debate with them, and to go out into the London streets alive with ideas’. I don’t have any bloody ideas, I just moan all the time. And so he [Jeremy] has the ideas, and he said ‘Are you sure?’ I said ‘Yeah, get Snape, he’s a bloody mountaineer, he’s halfway up K2 at the moment, get him to come down and do this and you talk to these thinking people.’ That is why I love the RGS. You talk to these thinking people, they may agree, they may disagree, but you know it and you’ll have set some little spark alight to make them think afresh and think differently. He did it with me, I hope he does it with you right now, ladies and gentleman, Jeremy Griffith.