The Human Condition Documentary Proposal—Part 2 Soul

Maternalism

The other means by which Negative Entropy or God could overcome the impasse to integrating multicellular animals created by the limitation of genes having to be selfish was through nurturing. Evidence overwhelmingly indicates that it was this nurturing path to integration that our ape ancestors took.

The nurturing trait is selfish, as genetic traits normally have to be, for through the act of nurturing and fostering the next generation the nurturing trait is selfishly ensuring its survival from generation to generation. However while nurturing is a selfish trait, from an observer’s or recipient’s point of view it appears to be selfless behaviour. After all, the mother is giving her offspring food, warmth, shelter and protection for apparently nothing in return. This point is significant because it means from the infant’s perspective, its mother is treating it with real love, unconditional selflessness. The infant’s brain is therefore being trained or conditioned or indoctrinated with selflessness, and with enough training in selflessness that infant will grow to be an adult that behaves selflessly.

Page 22 of Print Edition The ‘trick’ in this ‘love-indoctrination’ process lies in the fact that nurturing is encouraged genetically because the better infants are cared for the greater are their chances of survival. There is however an integrative side effect, in that the more infants are nurtured the more their brain is trained in unconditional selflessness. There are very few situations in biology where animals appear to behave selflessly towards other animals; as mentioned, they normally compete selfishly for food, shelter, territory and mating opportunities. Maternalism, a mother’s fostering of her infant, is one of the few situations where an animal appears to be behaving selflessly towards another animal. It was this appearance of selflessness that provided the opportunity for the development of love-indoctrination or training in love in our ape ancestors.

To develop nurturing—this ‘trick’ for overcoming the genetic learning system’s inability to develop unconditional selflessness—a species required the capacity to allow its offspring to remain in the infancy stage long enough for the infant’s brain to become trained or indoctrinated with unconditional selflessness or love. Being semi-upright as a result of their tree-living, swinging-from-branch-to-branch, arboreal heritage, primates’ arms were semi-freed from walking and thus available to hold dependants. Infants similarly had the capacity to latch onto their mother’s bodies. This freedom of the upper body meant primates were especially facilitated for prolonging their offspring’s infancy and thus developing love-indoctrination. A species that cannot carry and thus easily look after its infants and where the infants can’t easily hold onto their mothers cannot prolong infancy and thus develop love-indoctrination. For example, gazelle fawns have to be up on their feet and out of the vulnerable infant state within minutes of being born if they are to survive. It follows then that as the nurturing, love-indoctrination process developed our primate ancestor would have become increasingly upright. Humans’ bipedalism is a direct result of the love-indoctrination process and as such, must have occurred early on in the emergence of humans, as fossil records now confirm.

While bipedalism was the key factor in developing nurturing, other requirements, in particular ideal nursery conditions, also played a pivotal role.

If the available food, shelter and space was compromised, or other difficulties and threats from predators excessive, then we can assume that there would have been a strong inclination to revert to more selfish and competitive behaviour. The successful nurturing of infants required ample food, comfortable conditions and security from external threats. However, it wasn’t enough to simply look after them, the infants had to be loved, and so maternalism became about much more than mothers simply protecting their young; it became about actively loving them. Significantly, we speak of ‘motherly love’, not ‘motherly protection’.

Taking into account all of these considerations, love-indoctrination was an extremely ‘difficult’ development even for primates. It also has to be remembered that delaying maturity, as love-indoctrination does, postpones the addition of new generations that are so vital for the maintenance of a species limited mostly to single-offspring births. New generations ensure variety. The many challenges involved would explain why many primate species haven’t been able to significantly develop love-indoctrination and thus cooperative integration.

The bonobos or pygmy chimpanzees, or Pan paniscus as they are scientifically termed, live in the food-rich, shelter-affording ideal nursery conditions of the rainforests south of the Congo River and are by far the most cooperative/ harmonious/ cohesive/ integrated primate species. The comparative comfort of the bonobos’ environment and their cooperativeness is evident in this quote: ‘we may say that the pygmy chimpanzees historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food. Pygmy chimpanzees appear conservative in their food habits and unlike common chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive Page 23 of Print Edition social structure and elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior. In contrast, common chimpanzees have gone further in developing their resource-exploiting techniques and strategy, and have the ability to survive in more varied environments. These differences suggest that the environments occupied by the two species since their separation by the Zaire [Congo] River has differed for some time. The vegetation to the south of the Zaire River, where Pan paniscus is found, has been less influenced by changes in climate and geography than the range of the common chimpanzee to the north. Prior to the Bantu (Mongo) agriculturists’ invasion into the central Zaire basin, the pygmy chimpanzees may have led a carefree life in a comparatively stable environment’ (The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall L. Susman, ch.10 by Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, 1984).

And yet, in an indication of just how difficult it is developing love-indoctrination, even the bonobos living as they do in their ideal conditions have found it necessary to employ sex as an appeasement device to help subside residue tension between individuals.

Developing love-indoctrination to the point where the indoctrinated love or unconditional selflessness or altruism or morality becomes instinctive (a process that will be explained shortly) was akin to trying to swim upstream to an island; any difficulty or breakdown in the nurturing process and you are ‘swept back downstream’ once more to the old competitive, selfish, each-for-his-own, opportunistic situation.

In the context of our own human origins, it follows that for our ape ancestors to have become totally cooperative, as is asserted occurred, they must have lived in ideal nursery conditions in their home somewhere in Africa. (We know from fossil evidence that our original ancestors emerged in Africa but we don’t as yet know the exact location of this original ‘nursery’.)

It should be explained that there is a limiting factor in the development of love-indoctrination that needed to be overcome. While the nurturing of infants is strongly encouraged genetically, because it ensures greater infant survival, the side effect of training infants to behave selflessly as adults is that the selflessly behaving and even self-sacrificing adults don’t tend to reproduce their genes as successfully as selfishly behaved adults. The genes of exceptionally maternal mothers don’t tend to endure because their offspring tend to be the most selflessly behaved; they are too ready to put others before themselves. The more aggressive, competitive and selfish individuals take advantage of their selflessness, with males in particular seizing any mating opportunities for themselves. It’s that old joke, ‘the meek will inherit the Earth, if that’s alright with you blokes’; in other words, ‘you’ve got fat chance of that ever happening mate while we tough men are around’.

While the problem of selfish opportunism breaking out could be substantially countered by ensuring all members of the group were equally well nurtured with love, equally trained in selflessness, this all-equally-nurtured situation would be a delicate one to maintain. As mentioned, any breakdown in nurturing and the situation reverts to the old each-for-his-own structure. It is clear then that ideal nursery conditions were critical to ensure there was no disruption to the all-important task of nurturing.

While unconditional selflessness can be developed through love-indoctrination, due to the greater initial survival rate of infants who have been well nurtured—and their selfless training—it was clearly a very difficult and slow process. What was needed was a mechanism to assist and speed up the development of integration. That mechanism took the form of sexual or mate selection.

In the synopsis of Part 3 of this proposed documentary series it will be explained how the nurturing, love-indoctrination process liberated consciousness in our ape ancestors. It was the emerging conscious intellect in our forebears that began to support the development of selflessness. As our ape ancestors gradually became conscious they began to recognise the importance of selflessness and as a result began to actively select for it. (With regard to being able to ‘recognise the importance of selflessness’, while the Page 24 of Print Edition integrative, selfless, loving theme and purpose of existence has been denied by humans suffering from the human condition, it is an obvious truth to a conscious being who is not living in denial of it—every object or ‘thing’ around us is a hierarchy of selfless, cooperative, ordered matter.) Our ancestors could carry out this selection for selflessness by consciously seeking out love-indoctrinated mates, members of the group who had experienced a long infancy and exceptional nurturing and were closer to their memory of their love-indoctrinated infancy; that is, younger. The older individuals became, the more their infancy training in love wore off. Our ape ancestors began to recognise that the younger an individual, the more integrative he or she was likely to be. They began to idolise, foster and select youthfulness because of its association with cooperative integration. The effect, over many thousands of generations, was to retard our physical development so that we lost most of our body hair and became more infant-looking in our appearance as adults compared with our adult ape ancestors. This explains how we came to regard neotenous (infant-like) features—large eyes, dome forehead, snub nose and hairless skin—as beautiful.

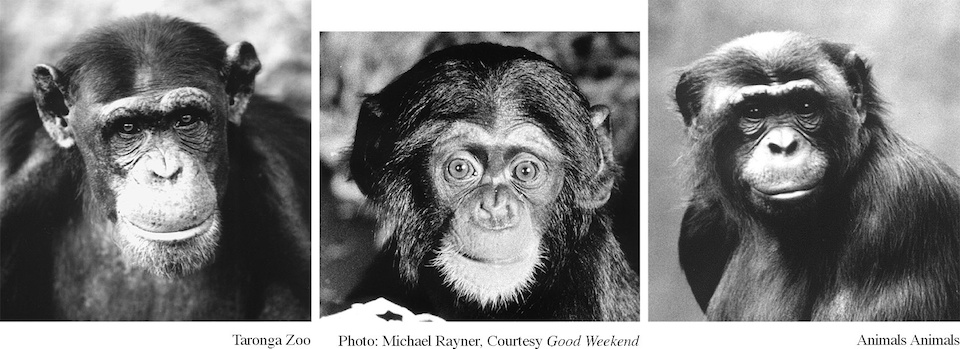

The following three photographs, of an adult common chimpanzee, an infant common chimpanzee and an adult bonobo, show the similarity between the adult bonobo and the infant common chimpanzee, indicating the effects of neoteny.

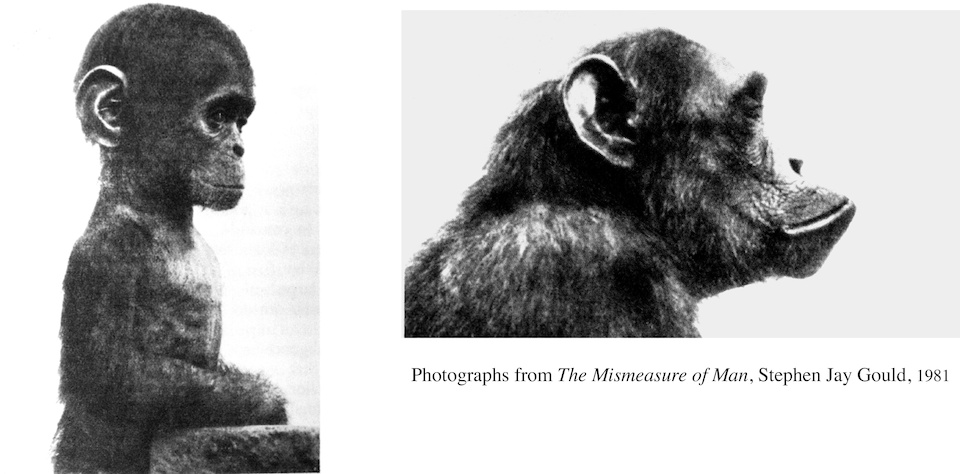

These photographs of an infant and adult common chimpanzee show the greater resemblance humans have to the infant, illustrating the influence of neoteny in human development.

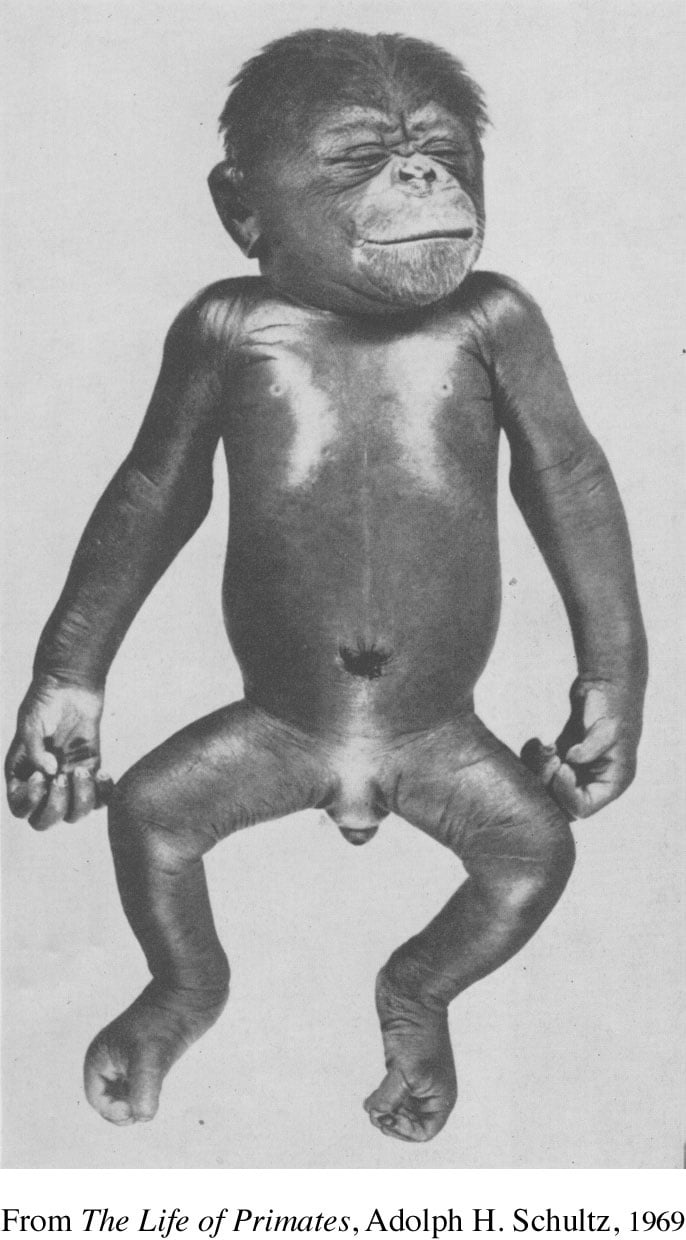

Page 25 of Print Edition This photograph of a common chimpanzee foetus at seven months shows body hair on the scalp, eyebrows, borders of the eye lids, lips and chin, precisely those places where hair is retained in adult humans, again illustrating the influence of neoteny in human development. Clearly, humans are an extremely neotenised ape.

Since before love-indoctrination emerged males were preoccupied with competing for mating opportunities, females must have been first to select for integrativeness by favouring integrative rather than competitive and aggressive mates. This helped love-indoctrination subdue the males’ divisive competitiveness.

Despite being unaware of this process of love-indoctrination, primatologists have verified sexual selection of cooperative integrativeness by females: ‘Male [baboon] newcomers also were generally the most dominant while long-term residents were the most subordinate, the most easily cowed. Yet in winning the receptive females and special foods, the subordinate, unaggressive veterans got more than their fair share, the newcomers next to nothing. Socially inept and often aggressive, newcomers made a poor job of initiating friendships’ (Shirley Strum, National Geographic mag. Nov. 1987); and ‘The high frequencies of intersexual association, grooming, and food sharing together with the low level of male-female aggression in pygmy chimpanzees may be a factor in male reproductive strategies. Tutin (1980) has demonstrated that a high degree of reproductive success for male common chimpanzees was correlated with male-female affiliative behaviours. These included males spending more time with estrous females, grooming them, and sharing food with them’ (The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall L. Susman, ch.13 by Alison & Noel Badrian, 1984, p.343 of 435).

By assessing a primate species’ ability to develop love-indoctrination and sexual selection, and hence develop integration, it should be possible to compare where each species stands on the integration ladder.

A comparison between bonobos and common chimpanzees clearly evidences what has been said about the love-indoctrination, sexual selection process, for the bonobos make visible the entire process. Indeed if it wasn’t for the bonobos the all-important role played by nurturing in the emergence of humans would be difficult to verify and denial of our nurtured origins might reign forever. (The need for this denial of the importance of nurturing in the emergence of humans and in our individual lives will be explained shortly.)

Common chimpanzees are found in equatorial Africa, north and east of the Congo River. The social model of the common chimpanzee is patriarchal or male-dominated. Although there is a focus on nurturing of the young by common chimpanzee mothers, the environment in which the females live is often disturbed by the males’ aggressive competition for mating opportunities. Further, the climatically and geographically unstable environments in which common chimpanzees live means their social bonds are periodically subjected to stress, such as from food scarcities during drier times. This pressured existence also results in fierce inter-group confrontation. Common chimpanzees also regularly hunt colobus monkeys as a source of protein.

In contrast, the bonobos live in the ideal nursery conditions of the warm climate south of the Congo River, a stable environment that offers ample food and the safety of the Page 26 of Print Edition jungle’s canopy for sleeping, travelling and shelter. As a result, the social model of the bonobos is vastly different to that of the common chimpanzees.

Firstly, the social dynamic of the bonobo society features a gender reversal to that of the common chimpanzees. Bonobo females form alliances and dominate social groups—distinctly male activities in common chimpanzee society. Bonobo societies are matriarchal, female-dominated, controlled and led and the entire focus of the social group seems to be concentrated on the maternal or female role of nurturing infants. Bonobo females have, on average, one offspring every five to six years and provide better maternal care than do common chimpanzees. Bonobo infants are born small and stay in a state of infancy and total dependence for a relatively long period of time. They also develop more slowly than other ape infants. Bonobos are weaned at about five years of age while common chimpanzees are weaned at about four years. Amongst primates only the bonobos have well-developed breasts similar to those of humans, presumably due to the bonobos’ emphasis on nursing. The primatologist Takayoshi Kano is one of the world’s leading experts on bonobos and, since 1973, has led the longest-running study of bonobos in their natural habitat at a site in Wamba, Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). In an interview conducted with Kano, his long-time collaborator Suehisa Kuroda commented: ‘The long dependence of the son may be caused by the slow growth of the bonobo infant, which seems slower than in the [common] chimpanzee. For example, even after one year of age, bonobo infants do not walk or climb much, and are very slow. The mothers keep them near. They start to play with others at about one and a half years, which is much later than in the [common] chimpanzee. During this period, mothers are very attentive…Female juveniles gradually loosen their tie with the mother and travel further away from her than do her sons’ (Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, Frans de Waal & Frans Lanting, 1997, p.60 of 210). The bond between the mother and her son is of particular importance in bonobo society. The son will maintain his connection with his mother for life and will depend upon her for his social standing within the group. The son of the society’s dominant female, the strong matriarch that maintains social order, will rise in the ranks of the group. This presumably ensures the establishment and perpetuation of unaggressive, non-competitive, cooperative male characteristics, both learned and genetic, within the group. Historically it is the primate males who have been particularly divisive in their aggressive competition to win mating opportunities and therefore the gender most needing of love-indoctrination. This quote makes the point: ‘Patient observation over many years convinced [Takayoshi] Kano that male bonobos bonded with their mothers for life. That contrasts with [common] chimpanzee males who rarely have close contact with their mothers after they grow up, instead joining other males in never-ending tussles for dominance’ (article Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war by Paul Raffaele, Last Tribes on Earth.com website).

Biologist and psychologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh is America’s leading ape-language researcher. In Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind (1994), authors Savage-Rumbaugh and Roger Lewin offer this insight into bonobo society and its emphasis on nurturing: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among common chimps, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. Page 27 of Print Edition If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong. This high regard for infants gives bonobo females a status that is not shared by common chimpanzee females, who must bear the burden of child care all alone. Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group, with males invited in to the extent that they are cooperative and

helpful. High-status males are those that are accepted by the females, and male aggression directed toward females is rare even though males are considerably stronger’ (p.108 of 299).

An extract from the 1995 National Geographic documentary The New Chimpanzees (featured in the pilot DVD of Part 2 of this proposed documentary) provides a good example of the important role a strong matriarchy plays in the prevention of divisive selfish and aggressive behaviour. To quote from the narration: ‘An impressively stern [bonobo] female enters and snaps a young sapling. Once she picks herself up she does something entirely surprising for a female chimp, she displays [the female is shown assertively dragging the sapling through the group], and the males give her sway [a male is shown cowering out of her way]. For this is the confident stride of the group’s leader, its alpha female, whom [Takayoshi] Kano has named Harloo.’

Bonobos are much gentler in their behaviour than their common chimpanzee cousins. They are relatively placid, peaceful and egalitarian, exhibiting a remarkable sensitivity to others. In fact physical violence almost never occurs in bonobos yet is customary amongst common chimpanzees. Male aggression has been tamed and unlike other great apes, there is little size difference between the male and female of the species. As mentioned, even sex has been employed by bonobos as an appeasement tool for subsiding conflict and tension. While infanticide is not uncommon amongst common chimpanzees it appears to be non-existent within bonobo societies where the group cares for even orphan bonobos. In common chimpanzee society orphans are occasionally adopted by a female but are not especially cared for by the group. Social groups of bonobos are much more stable than social groups of common chimpanzees with bonobos periodically coming together in large, harmonious, stable groups of up to 120 individuals. Anthropologist Barbara Fruth spent nine years studying bonobos in their natural habitat and observed that ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together and that that would not be possible with common chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between the rival groups’ (article Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war by Paul Raffaele, Last Tribes on Earth.com website).

Bonobos have more slender upper bodies than common chimpanzees and are more arboreal. Bonobos often walk upright; in fact they are by far the most upright of the great apes. It has long been claimed that it was the move to savanna and the need to see over tall grass that led to upright walking yet the bonobos live in the jungle, so some other influence must be at work that is selecting for upright walking and, as described, the evidence indicates that that influence was the need to develop nurturing.

Unlike common chimpanzees bonobos regularly share their food and while the former restrict their plant-food intake to mainly fruit, bonobos eat leaves and plant pith as well as fruit, a diet more like that of gorillas. While bonobos have been known to capture and eat small game they are not known to systematically hunt down and eat large animals such as monkeys, as common chimpanzees do.

As mentioned, bonobos are remarkably neotenous in their physical features. There is also a marked variance in features between individual bonobos, suggesting the species is rapidly changing. This in turn indicates the bonobo species has hit upon some opportunity that facilitates a rapid development. Evidence indicates that that opportunity is the ability to develop integration through love-indoctrination and mate selection.

The following section of dialogue about bonobos comes from a 1996 Discovery Channel documentary titled The Ultimate Guide: Great Apes. It confirms some of the main points that have been made about bonobos thus far. The segment commences with the Page 28 of Print Edition following observation by primatologist Jo Myers Thompson: ‘A female [common] chimpanzee’s life is rugged. They have hardships just in daily activities. They are probably lower on the hierarchy, the social status, than males throughout the society and for instance males beat them up, chase them, bully them around and that doesn’t happen in bonobo society. The female bonobos are not bullied and chased. Although there can be some male aggression it’s very minor. Female bonobos are never raped as far as we know; they have first choice at feeding sites. Their life is much more peaceful.’ The program’s narrator then states: ‘The physical difference between [common] chimps and bonobos are quite telling. Bonobos have shorter, smaller faces and a more slender physique retaining many of the features seen in juvenile [common] chimps. They’re rather like [common] chimps frozen inside adolescent bodies. Even their voices are high-pitched and child-like. The male aggression that is so common in [common] chimps is much reduced in bonobos and even relations between neighbouring groups are often peaceful.’ Thompson concludes: ‘Why do they [bonobos] need to be aggressive? They don’t have to fight for food, they don’t have to fight for sex, they don’t have to fight for inter-relationships, they don’t have to fight for space. Why would they be aggressive?’

As will be illustrated by the quotes that follow shortly, bonobos are exceptionally intelligent, almost certainly the most intelligent species after humans. In Part 3 of this series, it will be explained how nurturing liberated consciousness and, with it, intelligence. The fact the bonobos have been able to develop such a high degree of nurturing and are also so intelligent will evidence this coming explanation for the origin of consciousness.

In summary, the bonobos are the most peaceful, cooperative and intelligent of all apes. In fact, it is predicted that bonobos will come to be recognised as a species living on the very threshold of the metaphorical ‘Garden of Eden’, ‘golden’, completely cooperative state where humans once lived, as is being asserted here. Alarmingly however, bonobos—which were only identified as a species separate from common chimpanzees in 1929—are considered an endangered species today. However it is anticipated that once humans overcome our insecurity about our own corrupted, ‘fallen’ state (the topic of Part 4), and realise the acute value bonobos represent in terms of understanding the origins of humanity, bonobos will receive their just recognition; they will become a treasured part of our common heritage. The concern is however, will our ignorance of the bonobo’s true value, and resentment towards them for being so ideally behaved result in their extinction before they are able to take this extremely valuable place in our future. Bold, visionary efforts will be required to preserve them.

The following quote provides insight into how extraordinarily sensitive, cooperative, loving and intelligent bonobos are, and just how few exist in captivity: ‘Barbara Bell…a keeper/trainer for the Milwaukee County Zoo…works daily with the largest group of bonobos (5 males and 4 females, ranging in age from 3 to 48 years) in North America, making it the second largest collection in the world (the largest can be found at the Dierenpark Planckendael, in Mechelen, Belgium). There are only 120 captive worldwide. “It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day,” she says. “They’re extremely intelligent.”…“They understand a couple of hundred words,” she says. “They listen very attentively. And they’ll often eavesdrop. If I’m discussing with the staff which bonobos (to) separate into smaller groups, if they like the plan, they’ll line up in the order they just heard discussed. If they don’t like the plan, they’ll just line up the way they want.” “They also love to tease me a lot,” she says. “Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh. But what really blows me away is their ability to understand a situation entirely.” For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. “They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go,” says Bell. “That’s pretty amazing. Adults demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other.” The bonobo’s apparent ability to empathize, in contrast with the more hostile and aggressive bearing of the related [common] chimpanzee, has Page 29 of Print Edition some social scientists re-thinking our behavioral heritage’ (The Bonobo: “newest” apes are teaching us about ourselves, Anthony DeBartolo, Chicago Tribune, 11 June 1998).

Primatologist Frans de Waal and photographer Frans Lanting’s 1997 book, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, features another description from Barbara Bell of the truly extraordinary empathy and kindness that exists between bonobos. Fittingly, the extract comes from a chapter titled Sensitivity: ‘Kidogo, a twenty-one-year-old bonobo at the Milwaukee County Zoo suffers from a serious heart condition. He is feeble, lacking the normal stamina and self-confidence of a grown male. When first moved to Milwaukee Zoo, the keepers’ shifting commands in the unfamiliar building thoroughly confused him. He failed to understand where to go when people urged him to move from one place to another. Other apes in the group would step in, however, approach Kidogo, take him by the hand, and lead him in the right direction. Barbara Bell, a caretaker and animal trainer, observed many instances of such spontaneous assistance and learned to call upon other bonobos to move Kidogo. If lost, Kidogo would utter distress calls, whereupon others would calm him down or act as his guides’ (p.157 of 210).

The same book contains this description of the bonobo’s apparent sensitivity to other creatures: ‘Betty Walsh, a seasoned animal caretaker, observed the following incident involving a seven-year-old female bonobo named Kuni at Twycross Zoo in England. One day, Kuni captured a starling. Out of fear that she might molest the stunned bird, which appeared undamaged, the keeper urged the ape to let it go. Perhaps because of this encouragement, Kuni took the bird outside and gently set it onto its feet, the right way up, where it stayed, looking petrified. When it didn’t move, Kuni threw it a little way, but it just fluttered. Not satisfied, Kuni picked up the starling with one hand and climbed to the highest point of the highest tree, where she wrapped her legs around the trunk, so that she had both hands free to hold the bird. She then carefully unfolded its wings and spread them wide open, one wing in each hand, before throwing the bird as hard as she could towards the barrier of the enclosure. Unfortunately, it fell short and landed onto the bank of the moat, where Kuni guarded it for a long time against a curious juvenile. By the end of the day, the bird was gone without a trace or feather. It is assumed that, recovered from its shock, it had flown away’ (p.156).

In Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, Savage-Rumbaugh describes the extreme elation and affection shown by the young adult male Kanzi, her famous bonobo research subject, when reunited with his mother Matata after a number of months apart: ‘I sat down with him [Kanzi] and told him there was a surprise in the colony room. He began to vocalize in the way he does when expecting a favored food—“eeeh….eeeh….eeeh.” I said, No food surprise. Matata surprise; Matata in colony room. He looked stunned, stared at me intently, and then ran to the colony room door, gesturing urgently for me to open it. When mother and son saw each other, they emitted earsplitting shrieks of excitement and joy and rushed to the wire that separated them. They both pushed their hands through the wire, to touch the other as best they could. Witnessing this display of emotion, I hadn’t the heart to keep them apart any longer, and opened the connecting door. Kanzi leapt into Matata’s arms, and they screamed and hugged for fully five minutes, and then stepped back to gaze at each other in happiness. They then played like children, laughing all the time as only bonobos can. The laughter of a bonobo sounds like the laughter of someone who has laughed so hard that he has run out of air but can’t stop laughing anyway. Eventually, exhausted, Kanzi and Matata quieted down and began tenderly grooming each other’ (pp.143—144 of 299).

When thinking of our human plight—of suffering from insecurity about our human condition of being competitive and aggressive when the ideals are to be cooperative and loving—it can be seen that the bonobos, with all their social harmony, gentleness, sensitivity, empathy, selflessness, exceptional maternalism and favouritism towards the more nurtured, cooperative members, are extremely exposing and confronting for us. It is no wonder that the bonobos are, as Frans de Waal and Frans Lanting titled their book, The Forgotten Ape—or that ‘De Waal’s bonobo research [which acknowledges the ‘sensitivity’ of Page 30 of Print Edition bonobos, as shown in the quotes from his book] came under sustained attack’ from some anthropologists (article The Future of Bonobos: An Animal Akin to Ourselves by Douglas Foster, from the Alicia Patterson Foundation website, www.aliciapatterson.org). Thankfully, as will be revealed in Part 4 of these synopses, humans are in fact the great heroes on Earth, not the evil villains we have lived in such fear and insecurity of being.

In Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind Savage-Rumbaugh states: ‘even though I could describe on paper, with proper scientific documentation, what Kanzi did, I knew that I needed to show people images of Kanzi as a living, breathing, thinking being. My words and numbers were but the pale bits and fragments we call data, data that was dwarfed by the presence and power of Kanzi himself’ (p.7 of 299). Due to mechanistic science’s compliance with humanity’s need to live in almost complete denial of anything to do with the all-loving, integrative, instinctive world of our soul, it is virtually impossible for the discipline, as it operates today, to allow any truth out about how extraordinarily integratively orientated bonobos are. Visual footage and images of bonobos are about the only means by which the truth can be revealed. Even the anecdotes offered above reveal more holistic, denial-free insights into the world of bonobos than all the mechanistic detail given earlier. The footage of bonobos included in the pilot DVD of Part 2 of this proposed documentary series is testament to this fact. These few precious minutes serve to dramatically evidence all that has been said about the love-indoctrination, sexual selection process. In particular you will see truly extraordinary footage of Kanzi mediating in a dispute between Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and a bonobo called Tamouli. You will see the hurt expression on the face of a bonobo called Panbanisha when she is reprimanded for over-exuberant behaviour. While in bonobo society ‘infants can do no wrong’, they are never disciplined, in our human condition-afflicted, chaotic and pressured world discipline is sometimes necessary.

To context how successful other primates have been in developing integration through love-indoctrination and mate selection, gorillas appear to have been more successful than common chimpanzees, yet not as successful as bonobos; for example, gorilla societies are still patriarchal or male-dominated. Interestingly, while bonobos depended on the safety of trees for the secure, threat-free environment needed to develop love-indoctrination, gorillas apparently selected for physical size and great strength, particularly in the males of the species, to protect their groups from outside, predatory threats. To quote anthropologist Adolph H. Schultz, the adult male gorilla ‘is a remarkably peaceful creature, using its incredible strength merely in self-defence’ (The Life of Primates, 1969).

The legendary and visionary palaeontologist Louis Leakey foresaw ‘that knowledge of the past would help us to understand and possibly control the future’ (Disclosing the Past, Mary Leakey, 1984), and in 1959, against prevailing views, began the search for fossil evidence of the emergence of humans in Africa. The search was to prove stunningly successful. In another inspired move he handpicked three women to study the great apes in their natural habitat—Jane Goodall, who began her field study of common chimpanzees in 1960; Dian Fossey, who began her field study of gorillas in 1967; and Birute Galdikas, who began her field study of orangutans in 1971.

Dian Fossey proved to be extraordinarily courageous in her readiness to acknowledge the gentleness, cooperativeness and importance of nurturing amongst gorillas. The universally practiced denial-complying variety of science held little sway over her. It seems appropriate that after she was murdered at her research station in Rwanda in 1985 she was buried alongside her gentle gorilla friend Digit, who had given his life defending his group from poachers.

The following extracts from Fossey’s 1983 book Gorillas in the Mist reveal the strong relationship between nurturing and integrativeness that is love-indoctrination: ‘Like human mothers, gorilla mothers show a great variation in the treatment of their offspring. The contrasts Page 31 of Print Edition were particularly marked between [the gorilla mothers] Old Goat and Flossie. Flossie was very casual in the handling, grooming, and support of both of her infants, whereas Old Goat was an exemplary parent’ (ch.9).

The effect of Old Goat’s ‘exemplary parenting’ of Tiger (her son) is apparent in the following extract: ‘Like Digit, Tiger also was taking his place in Group 4’s growing cohesiveness. By the age of five, Tiger was surrounded by playmates his own age, a loving mother, and a protective group leader. He was a contented and well-adjusted individual whose zest for living was almost contagious for the other animals of his group. His sense of well-being was often expressed by a characteristic facial “grimace” ’ (ch.10). The ‘growing cohesiveness’ (developing integration) brought about by ‘loving mothers and protective leaders’ is love-indoctrination.

Dian Fossey’s account of the love-indoctrinated Tiger later in life illustrates how nurtured love is required to produce the integrated group. It describes how the secure, integrative, loving Tiger tried to maintain integration or love in the presence of an aggressive, divisive gorilla after the group’s integrative silverback leader, Uncle Bert, was shot by poachers: ‘The newly orphaned Kweli, deprived of his mother, Macho, and his father, Uncle Bert, and bearing a bullet wound himself, came to rely only on Tiger for grooming the wound, cuddling, and sharing warmth in nightly nests. Wearing concerned facial expressions, Tiger stayed near the three-year-old, responding to his cries with comforting belch vocalizations. As Group 4’s new young leader, Tiger regulated the animals’ feeding and travel pace whenever Kweli fell behind. Despondency alone seemed to pose the most critical threat to Kweli’s survival during August 1978. Beetsme…was a significant menace to what remained of Group 4’s solidarity. The immigrant, approximately two years older than Tiger and finding himself the oldest male within the group led by a younger animal, quickly developed an unruly desire to dominate. Although still sexually immature, Beetsme took advantage of his age and size to begin severely tormenting old Flossie three days after Uncle Bert’s death. Beetsme’s aggression was particularly threatening to Uncle Bert’s last offspring, Frito [son of Flossie]. By killing Frito, Beetsme would be destroying an infant sired by a competitor, and Flossie would again become fertile. Neither young Tiger nor the aging female was any match against Beetsme. Twenty-two days after Uncle Bert’s killing, Beetsme succeeded in killing fifty-four-day-old Frito even with the unfailing efforts of Tiger and the other Group 4 members to defend the mother and infant…Frito’s death provided more evidence, however indirect, of the devastation poachers create by killing the leader of a gorilla group. Two days after Frito’s death Flossie was observed soliciting copulations from Beetsme, not for sexual or even reproductive reasons—she had not yet returned to cyclicity and Beetsme still was sexually immature. Undoubtedly her invitations were conciliatory measures aimed at reducing his continuing physical harassment. I found myself strongly disliking Beetsme as I watched his discord destroy what remained of all that Uncle Bert had succeeded in creating and defending over the past ten years…I also became increasingly concerned about Kweli, who had been, only a few months previously, Group 4’s most vivacious and frolicsome infant. The three-year-old’s lethargy and depression were increasing daily even though Tiger tried to be both mother and father to the orphan. Three months following his gunshot wound and the loss of both parents, Kweli gave up the will to survive…It was difficult to think of Beetsme as an integral member of Group 4 because of his continual abuse of the others in futile efforts to establish domination, particularly over the indomitable Tiger…Tiger helped maintain cohesiveness by “mothering” Titus and subduing Beetsme’s rowdiness. Because of Tiger’s influence and the immaturity of all three males, they remained together’ (ch.11).

It is clear from this account how very easily any disruption to the love-indoctrination process can lead to regression back to the competitive, opportunistic pre-love-indoctrination situation.

In the case of orangutans, love-indoctrinated integration is inhibited by the scarcity of food in their native forests of South East Asia. In fact orangutan infants are nurtured with love in a long infancy only to suffer being ‘thrown out of love’ when, as adults, they have Page 32 of Print Edition to set out and live mostly solitary lives due to the shortage of food. Older orangutans have a reputation for being morose and bad tempered—perhaps this ‘outcast’ existence is the cause.

In the case of baboons, a quote included earlier indicated female baboons are beginning to contain competitive male sexual opportunism, which implies baboons are able to develop some integration through love-indoctrination and mate selection. However, again, the environment in which baboons live is normally one in which food is not plentiful and this would seem to be the main limiting factor in developing love-indoctrination and thus integration amongst baboons.

Of the monkeys, the capuchins from South America have by far the largest brain to body size and are considered to be much more intelligent than other monkeys—yet they have not attained the level of consciousness where they have an awareness of the concept of ‘I’ or self and can recognise themselves in a mirror, as can bonobos, common chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and humans. Capuchin females are extremely maternal and nurse their infants for a longer period than other monkeys, weaning their infants in their second year. Both male and female capuchins live for over 40 years compared to the 20 odd years managed by most other monkeys, possibly reflecting the drawn out stages of maturation that may result from extending the infancy stage to allow for longer nurturing. Female capuchins decide when and with whom to mate, and have been observed to form successful coalitions against males. Male against male competition is less obvious amongst capuchins than in other monkeys and, like the bonobos, capuchins frequently engage in same-sex sexual interactions.

The following descriptions of the endangered muriqui or woolly spider monkeys indicate this species has been able to develop some degree of love-indoctrination: ‘Wrangham and Peterson suggest that a South American monkey, the muriqui, displays similar behaviours to the bonobo, with females being co-dominant, males less aggressive and females more sexual than other mammals’ (from www.massey.ac.nz/~kbirks/welcome.htm, website of Stuart Birk, senior lecturer at Massey University, New Zealand). ‘The mating system [of the muriqui] is polygamous, with individuals being promiscuous. Embracing is a behavior important to maintaining social bonds. There is very little aggression among group members. Males spend a large amount of time close together without aggressive encounters’ (references: Emmons & Feer 1997, Flannery 2000, Nowak 1999, from Animal Info—Muriquis on website www.animalinfo.org).

It needs to be explained that with love-indoctrination and mate selection of cooperativeness occurring over many generations, selflessness would have eventually become instinctive or innate. This is because once unconditionally selfless individuals were continually appearing, the genes ‘followed’ the whole process, reinforcing that selflessness. Similarly, when the conscious mind fully emerged within humans and, as will be explained in Part 4, went its own way—embarked on its course for knowledge—genetic adaptation followed, reinforcing that development. Generations of humans whose genetic make-up in some way helped them cope with the human condition were selected naturally—making humans’ alienated state somewhat instinctive in humans today. We have been ‘bred’ to survive the pressures of the human condition; to block out or deny the issue of the human condition has been our main way of coping with the dilemma of the human condition. Genes would inevitably follow and reinforce any development process—in this they were not selective. The difficulty was in getting the development of unconditional selflessness to occur, for once it was regularly occurring it would naturally become instinctive over time.

To relate this back to our human ape ancestors, it is being suggested that love-indoctrination and mate selection of cooperativeness occurred for a sufficiently long period for cooperative integrativeness to become an instinctive part of their/our make-up.

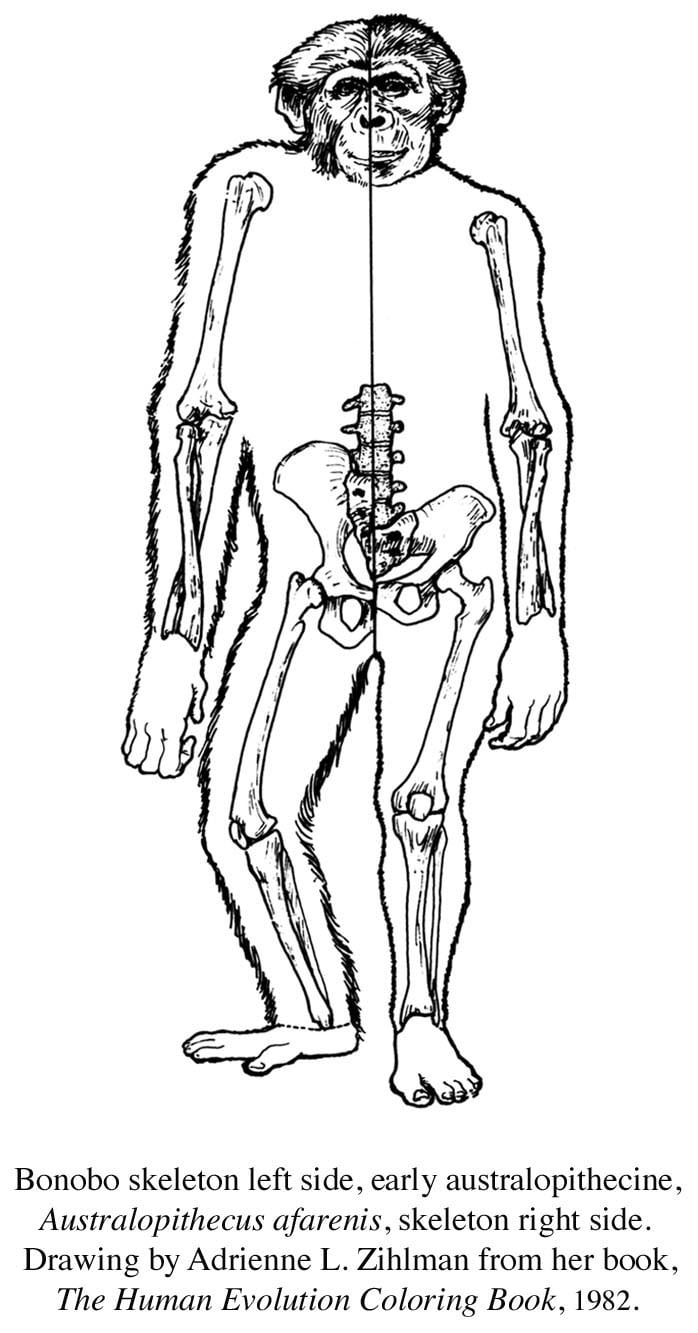

Page 33 of Print Edition Finally, it needs to be described how the bonobos, the most integrated variety of primates, compare with the fossil evidence of our human ancestors. ‘Lucy’, the three and a half million year old Australopithecus (afarensis) fossil ancestor of humans discovered in the Rift Valley of Africa, shows an amazing similarity to the bone structure of the bonobo. The two are very similar in brain size, stature and in the length of the lower limbs, and are fairly similar in overall body proportions. Lucy’s pelvis shows that she walked fully upright. The pelvis of bonobos, while not quite as adapted to upright walking as Lucy’s, is significantly more adapted to upright walking than the pelvises of common chimpanzees.

While we have not traditionally thought of humanity’s maturation as progressing through the same stages humans go through in our individual lives, since all the members of a variety of early humans would have shared a relatively similar mental and psychological state it makes sense that each variety of early humans can be described collectively by that shared mental and psychological state.

Individually we each mature from ‘infancy’ to ‘childhood’ to ‘adolescence’ to ‘adulthood’. To elaborate, infancy is when we develop sufficient consciousness to discover that we are at the centre of the changing array of experiences around us. We become aware of the concept of ‘I’ or self, which, as just mentioned, is what bonobos and the other great apes are capable of. Childhood is when we begin to actively experiment or ‘play’ with the power of conscious free will, the power to manage events to our own desired ends. Adolescence is when we become so consciously aware, so thoughtful that we encounter the sobering responsibility of free will and go in search of our identity, in search of who we are—in fact, as will be explained in Part 4, go in search of understanding of our corrupted state of the human condition. Adulthood is when we finally mature from insecure adolescence and become understanding of ourself at last and thus secure conscious managers of our world. In short, infancy is ‘I am’, childhood is ‘I can’, adolescence is ‘but who am I?’ and adulthood is ‘I know who I am’.

Love-indoctrination takes place in our infancy, when we are trained in love and become cooperative and integratively behaved. As will be explained in Part 3, infancy is also the period in which consciousness is liberated by the training in love. Since bonobos are approaching the state of complete integration and are exceptionally conscious and thus intelligent they are clearly approaching the end of the infancy stage, on the brink of ‘childhood’. As predicted earlier, bonobos will come to be recognised as a species living on the threshold of the metaphorical ‘Garden of Eden’, totally integrated, cooperative state.

To context where bonobos are in the journey negotiated by our human forebears, our ape ancestor was Infantman, which emerged some 12 million years ago with the emergence of apes. Infantman then gave rise to fully integrated, happy, untroubled, playful Childman, the australopithecines, which emerged some 5 million years ago. Thus, bonobos are where we were some 5 million years ago. The similarity of bonobo skeletons with the early australopithecine fossil skeleton of Lucy confirms this.

Page 34 of Print Edition To complete the description of our human journey thus far; some 2 million years ago the australopithecines matured into fully conscious, thoughtful, troubled, upset, human condition-burdened and insecure Adolescentman, Homo, us. Now, with the finding of understanding of our human condition-afflicted state of upset—the subject of Part 4 of this series—humanity is brought to the end of its insecure adolescent stage. The search for our species’ identity, for understanding of itself, particularly for understanding of why we became divisively behaved, has ended and our species can now enter its secure, fulfilled, peaceful adulthood.