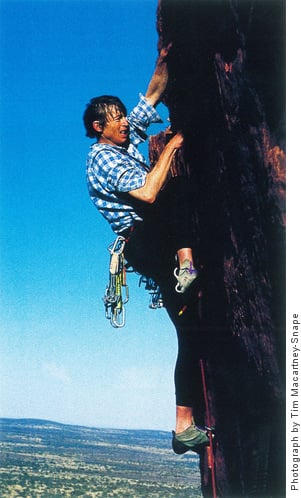

The June 1999 edition of Inside Sport magazine published

the following six-page profile on Tim Macartney-Snape.

Profile by James Elder | Images by Arunas

Tim Macartney-Snape is struggling

to conquer his toughest challenge yet

— reviving his reputation.

Even among his fellow elite mountaineers, Tim Macartney-Snape is regarded as a climber of freakish ability. Twice he has stood on top of the world. Many times faced death.

Always he has survived.

Back in 1984, after he and his team became the first Australians to mount a successful Everest assault, it was written by a fellow climber that Macartney-Snape “constantly astounds colleagues by his determination, endurance and energy at very high altitude, and did so again on this mountain...” While his companions counted the heavy cost of their exploits—one was physically and mentally destitute for days, another suffered severe frostbite—it was only Macartney-Snape who returned unscathed.

No falls, no frostbite. No fear.

Six years after that historic achievement, Macartney-Snape did what no man had (nor has since) ever achieved. It had once been quipped that only after starting at sea level could a mountaineer lay true claim to conquering Everest’s 8874 metres. And so Macartney-Snape walked the 1000km from the Bay of Bengal to the foot of Everest before the serious climbing began. Incredibly, his ascent was without additional oxygen, and solo. Scores of climbers have died on their Everest quests, and many more have lost some parts of their extremities to frostbite. But instead of cruelly shortened fingers or toeless feet, the 43-year-old Macartney-Snape has two Orders of Australia to show for his pains.

These might be satisfying and fulfilled days for Australia’s most distinguished mountaineer. But they’re not. The mountain man has taken his most serious fall. Since the screening in 1995 of an ABC Four Corners program, which portrayed him negatively for his role with an organisation called the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood (FHA), Tim Macartney-Snape has nursed a shattered reputation. Prior to the screening of the Four Corners film, Macartney-Snape was a popular voice on the speaking circuit, especially in schools. But the program charged that he used his fame and the podium to recruit young people to the Foundation.

“The FHA holds the view that we have a fundamental understanding of human nature which will help solve the problem of the human condition,” says Macartney-Snape. “That is, how we can be both selfless and selfish. We have ideas that I believe are worthy of debate.” Four Corners, Australia’s most respected current affairs program, presented the view that the Foundation was cυltish and that recruits were torn from their families and futures.

Soon after the program aired, demand for Macartney-Snape on the speaking circuit disappeared. He and the FHA subsequently complained to the Australian Broadcasting Authority (ABA), and in February of last year the ABA found against Four Corners. The ABA ruled that the program was unbalanced, made inaccurate assertions (that Foundation founder Jeremy Griffith compared himself to Jesus Christ), and failed “to present the principal relevant viewpoints in relation to Mr Macartney-Snape’s role as guest speaker.” The ABA suggested the ABC might broadcast an apology. Four Corners stands by the program, and claims flaws in the ABA process led to its finding. The ABC isn’t challenging the ruling, but no apology has been forthcoming.

For a man who has conquered the most inhospitable terrain on Earth, the episode has taken Tim Macartney-Snape into unfamiliar territory. “It’s been incredibly hard,” he says. “I’ve lost income and reputation and all that sort of stuff. Yes, my standard of living took a battering and I’ve lost some friends because of it.” More than any other individual, his ability to cope with the travails of Nature is beyond question. It remains to be seen how he copes personally with this man-made storm.

______________________

It is another chapter in an extraordinary life. Born in Africa, Macartney-Snape spent the first eight years of his life in southern Tanzania, before being sent to boarding school in the north of the country. There his classrooms opened out to the 4500m volcano Mt Meru and, nearby, Mt Kilimanjaro. “Climbing just seemed like a fascinating thing to do,” he says. “I’ve always wanted to go up and see what was over the horizon, and the best way of doing that was to climb a hill.”

At 12, his father moved the family to rural Victoria. Schooled at Geelong Grammar, where outdoor education was a focus, Macartney-Snape took fervidly to bushwalking, cross-country skiing and climbing. By the time he was at university, Macartney- Snape had graduated to serious mountaineering.

His rare climbing style began with Lincoln Hall 20 years ago. The two students from the Australian National University were with a group attempting to summit their first Himalayan climb, the 7066m Dunagiri. After six weeks of poor weather, the group leader decided the climb was off. They’d been forced to wait too long and the group was too tired. Macartney-Snape and Hall were sent up the mountain to retrieve the fixed ropes. As they climbed higher, Macartney-Snape says excitement took them over. “Bugger this,” they decided. “Let’s just go up and see what the summit ridge is like.”

It was the best afternoon of the whole trip, yet between them they carried only a bivvy bag, one water bottle, a tin of John West cherries and a few dried apricots. Still short of the summit and with darkness looming, the pair were forced to spend the night on the mountain. Next day, an exhausted Hall stopped 150m from the summit. Macartney-Snape pushed on. By noon he had completed his first Himalayan ascent. Meanwhile, Hall’s leather boots and strap-on crampons were restricting the flow of blood to his feet. Frostbite was setting in. As for Macartney-Snape? “Tim’s just more resilient to the cold,” says Hall. “He just powered on.” By the time the pair got back to the fixed ropes they’d set out for, both were badly dehydrated and there was still a precarious walk ahead of them along the side of a gorge through a harrowing blizzard. Macartney-Snape went ahead and arrived at camp at 2am. Hall came five hours later and was then airlifted back to Australia, where he had a couple of toes amputated.

“If you make a bad decision [while climbing], one of your options is death,” Macartney-Snape says, as if he’s talking about a bad day at the office. “That’s what makes climbing, and high-altitude climbing particularly, the pre-eminent physical challenge. There’s nothing else like it. It’s this combination of lack of oxygen, and the extreme situation, where if you make a mistake you’re dead. I thrive on the idea of digging deeper than you’ve ever had to dig before to make yourself keep going. That’s the ultimate climbing experience. No-one’s going to be able to come and rescue you; if you don’t keep going you’ll die, and if you’re not very careful about where you’re going you’re going to die as well.

“If you don’t push yourself and explore those boundaries,

if you just lead a pampered existence, then your luxurious, pampered surroundings become meaningless.”

“I like pushing myself to total exhaustion and the euphoria that comes with having achieved that,” he continues. “But it’s more than just endorphins running through the system, it’s the euphoria that comes through having overcome pain and hardship. If you don’t push yourself and explore those boundaries, if you just lead a pampered existence, then your luxurious, pampered surroundings become meaningless.”

This is the Macartney-Snape maxim. His metabolism is his means. “He’s obviously got the right kind of background hormonal balance,” says Emeritus Professor of Physiology at the University of NSW, Paul Korner. “He’s a phenomenal mountaineer.” According to Korner, Macartney-Snape’s red blood cells probably metabolise more economically than his peers, allowing him more oxygen more readily.

“He’s one of the strongest Himalayan climbers I’ve ever met, and I’ve met quite a few,” says his climbing colleague Greg Child, now living in Seattle. “He’s got this amazing success rate, having succeeded on most of the things he’s attempted. He takes to altitude incredibly well - he strides up the hill like a greyhound. He’s incredibly fit with great lungs. And he’s very calm: he takes all the scary, difficult, uncomfortable things that come at you on a mountain in his stride. He knows it’s coming, so when it comes he doesn’t seem bothered by it.”

Lincoln Hall, another distinguished Australian mountaineer and climbing partner, agrees: “You can be incredibly determined and not able to handle it, but Tim’s got the mind and the metabolism for mountaineering, and you need both. In mountaineering, the greatest rewards are when you’re working on the edge of your abilities and on the edge of life. Tim pushes a bit further, so he’s always working at the edge of his ability and always pushing those boundaries. I used to think that I was a slow climber, until I climbed with people other than Tim.”

Of his own mind and metabolism, Macartney-Snape says: “I can probably push myself harder than others. It’s like sprinting 100m but perpetually having that oxygen debt. Your body just doesn’t want to be there. So you’ve really got to push yourself. That’s the attraction.”

“At altitude, it’s not as if you can pull out if you don’t feel like it. You’re put in a situation where your bridges are basically burnt. And that’s the quintessential climbing experience: where all you’re relying on is your own cunning and resources to survive.”

“At altitude, your bridges are basically burnt. That's the quintessential climbing experience: all you’re relying on

is your own cunning and resources to survive.”

With his finances suffering and much of his time spent attempting to defend his and the Foundation’s name, Macartney-Snape has been forced to curtail his preferred style of climbing. Apart from a fledging outdoor equipment company, his sole source of income has become taking the inexperienced on climbs. While Macartney-Snape says he: enjoys helping these people explore regions they would- otherwise be unable to reach, he readily admits he’d rather climb for himself than for money. This man who says that “climbing expresses who I am” has been forced to cash in on his craft. Even in Australia, the home of the tall poppy syndrome, it’s a cruel chop - a bit like Mark Taylor being compelled to make a quid through coaching petulant kids.

“My wings have been clipped,” Macartney-Snape says soberly. “Yes, I would rather go on personal expeditions. Although I do like taking people trekking. It’s work, no doubt about it. You’re on duty 24 hours a day, and it’s frustrating because you can’t just go off and climb something. It’s like wandering around with hobbles.”

Macartney-Snape’s uncomplicated candour and shy, yet warm manner makes it easy to like him. Perhaps to pity him. He’s lost money, status and friends. (He’ll have nothing to do with either the man he first reached Everest with, Greg Mortimer, or Lincoln Hall until “they can respect my stance against former friends who aided and abetted the officially discredited Four Corners attack”). Yet sympathy seems misplaced for a man whose levels of physical endurance and mental discipline are beyond comprehension for all but his peers. And it is not sympathy he seeks.

“I wouldn’t have it any different,” he says. “If [the lost reputation, money and friends] is what it takes to get people to listen to the information we support, I’m quite happy to take that. The FHA is the mountain of my mind. It’s bigger than anything I’ve ever attempted and the ABC is just a crevasse. Climbing has taught me how to handle situations and be a better survivor. I’m sure that’s helped a lot in dealing with this whole attack.” Struggling or not, even the wildest imagination can’t envisage Macartney-Snape going detox on mountaineering. Tempt the addiction, stoke the craving to climb, and Macartney-Snape’s sunken eyes light up. Though it is unlikely he will seek the view from the top of the world again, he still talks feverishly of his need to keep exploring. “I don’t have any desire to go to a well-known peak, because they’re always going to be crowded. There are a couple of peaks in Nepal I’d like to climb. They’re largely unnamed, real virgin territory, meaning no-one’s probably reached the summit. That’s what I really like doing.”

Until then, he hopes to be part of an expedition to South Georgia in August. A mountainous island in the South Atlantic, due east of the northern tip of the Antarctic peninsula, South Georgia is about as remote as you can get. With three others, Macartney-Snape will sail in an ice-strengthened yacht from Chile and then attempt to become the first to traverse the island. “We’ll find an unclimbed peak or two and meet with the boat on the other side,” he says. “There’s a big difference between going somewhere where you know other people have been and going somewhere where people haven’t been, or where they’ve attempted but haven’t made it. That to me is the great challenge.”

______________________

In his office, surrounded by FHA letters and faxes of ABA rulings, Tim Macartney-Snape stares at a metre-long 360-degree photo of Mt Everest and the surrounding peaks. No-one could have foretold that a man who has twice touched the summit of the world’s highest mountain would now stare at it from such a distance. Macartney-Snape is silent. Perhaps, just for a moment, he is once more on that precipitous peak. Once more parrying the forces that would defeat lesser men. Surviving. He blinks, and the moment is gone.

“Come and look at this,” he says, heading upstairs toward his loft bedroom. On the sloping wall are rocks and foot holds. He has built his own climbing wall. “I use it just for practice,” he says. “Just when I need to escape and stretch out.”

It is time to go, so I leave him there. Still climbing.