Alan Jones and Graham Richardson interviewing Jeremy Griffith on the ‘Richo & Jones’ Sky News Australia television program, 29 January 2020

An article by Jeremy Griffith in The Spectator about bushfires attracted great interest in Australia. As a result, Jeremy was interviewed by Australia’s leading broadcaster Alan Jones on his top rating breakfast radio show on 2GB. Later that night Jeremy appeared on the Richo & Jones show on Sky News Australia. During the segment, Graham Richardson described Jeremy’s writing as ‘brilliantly written’, and Alan Jones again praised the clarity of Jeremy’s insights, saying, ‘you have written a brilliant piece’.

See the TV interview here:

Transcript:

Alan Jones: Thank you for being with us. Look, as I mentioned to you before the break, this is something that has never ever, ever, been discussed, and thank God it’s going to be tonight.

As I have already told you, yesterday I toured again the bushfire devastation for miles around Batemans Bay. Batemans Bay is on the south coast of New South Wales, in the Eurobodalla Shire, which I might add is 85 percent national park; a beautiful spot—beaches, seafood, oysters. It’s 140 miles, 226 kilometres from Sydney, population about 11,000. Much of it a bomb-site, but equally much of the community intact. Visit them. Spend up. Support them. The point we want to make here is very simple. As Jacob and I drove into Mogo yesterday [footage of burnt eucalypt forest is shown], there in their thousands—you can see them, look at them—they were silent, black sentinels; sentinels to destruction. In many ways, they are the agents themselves of that destruction. They’re eucalypts. They survive, nothing else does.

In an outstanding piece of writing in the most recent Spectator magazine, Jeremy Griffith, an Australian biologist, the founder of the non-profit World Transformation Movement, wrote a headline to his story; it said ‘eucalypts are incinerators from hell dressed up as trees’. Every farmer tell you this. Writes Jeremy Griffith: ‘evidence suggests that eucalypts originally emerged from our Australian rainforests and then quickly spread and conquered virtually the whole of Australia, with botanists recognising that every variety of plant community in Australia, be it heathland, scrub, open woodland or forest, is dominated by a variety of eucalypt’. And there they are. You just saw them; charred trunks, sentinels to the disaster they’ve helped create. As Jeremy Griffith said, ‘eucalypts are incinerators from hell dressed up as trees’. He’s joined us tonight in an issue which I believe is at the heart of this bushfire crisis.

Jeremy, thank you for your time, but why haven’t we woken up to this?

Jeremy Griffith: We’re living in denial. We love our gum trees, but that’s blocking us from seeing the real problem right in front of us.

Alan: You’ve said here these things actively cultivate fire. You said they have ‘very waxy, oily, flammable leaves, which they are constantly shedding to accumulate beds of fire-fuelling litter at their base, and peeling bark that flies through the air as lit tapers’. This is what people are talking about, the ember fires. They said here they could see it coming through the sky, from one tree to the other—they didn’t know what was happening—to start new fires many kilometres ahead.

And, as you say, ‘the Blue Mountains west of Sydney are so-named because the oil in the eucalypts along the mountain range is constantly evaporating and creating a blue haze’. You say ‘eucalypts are essentially fire-fuelling incinerators that generate so much heat when they catch fire that when one burns’, you say, so the others go…‘its radiant heat evaporates the oils in the neighbouring eucalypts creating a flammable gas which ignites as a fireball, and so the crowns of the trees explode’—that’s what everyone tells me they were hearing—‘with fire one after the other triggering a ‘crown fire’—a wave of exploding eucalypt canopies that raced through the Australian bush like a tornado’. That is precisely—not knowing what they were talking about—the people said they heard that.

Graham Richardson: Oh it’s brilliantly written. I mean that’s really good prose.

Alan: But this is what they heard. A tornado.

Graham: I don’t know, what do you do? Given that they dominate, they are the dominant tree in Australia, what do you do with the world?

Jeremy: I think the first issue is to face the truth of the real nature of eucalypts. I mean honestly, if eucalypts were human you’d lock them away as psychopaths. They’re ruthless killers, and that’s what we’ve got to face. I love trees. I grew up in the bush and my parents actually started the Burrendong Dam Arboretum; when I was a 16 year old, I was carrying buckets of water to start the now famous arboretum, a plant zoo. So I love trees, but this is really serious. The destruction that’s going on, the trauma in people’s lives, it is a war-zone—exactly as you’ve described it, Alan, it’s like a bomb’s gone off, and it’s right down the full length of this coast. When you fly over the east coast of Australia, what you see is this endless sea of eucalypts, and you see houses right in amongst them, and people love the trees—there’s just gonna be a reality check. We’ve got to face what the problem is, we’ve got to stop this madness. We’ve got to stop all the devastation and the heartache and the pain.

So we’ve got to deal with eucalypts, and the first thing is to face the extent of what they really are—and they are incinerators from hell dressed up as trees.

Graham: Should we have laws that prevent people from building in some of the areas, where the eucalypts are.

Jeremy: Well, I think if we start by, first of all, facing the true nature of eucalypts and realising that how dangerous they are—because there’s gonna be a post-mortem here and we’ve got to get it right from here-on. We’ve got to stop this; it’s a really serious problem, the eucalypts in Australia. So, to overstate it, I think that we’ll get where we will get to, eventually, is that even the idea of reforesting, revegetating, parts of the eucalypt forest is dangerous—they’ve got to be sectioned off and into an area that is very closely managed.

Alan: So you’ve made the point that Aboriginal fire, I think your words were, ‘aboriginal fire management worked brilliantly’, and we’ve ignored all of that.

Jeremy: Yes. Yes. Well, that’s an amazing situation; well how did this happen? You see eucalypts originally emerged from the rainforests, and they just spread and took over everything. So the question is, why did that happen? How did that happen? Well, they happened to have epicormic buds which live in the sapwood underneath the bark, and it so happens that they can survive fire when virtually no other species could. Lightning strikes will cause fire, but to be as successful, to have spread—because it’s such a chaotic species, it’s not nicely designed like a pine tree or an oak tree; they’re chaotic, they’re an upstart species—they’ve hit upon some some breakthrough adaption…

Alan: Indigenous Australians in the last fortnight have spoken about this. An outfit called Firesticks Alliance and their coordinator, Oliver Costello, and he’s been very outspoken—because no one listens to him, no one takes any notice, ‘they’ know everything—he says ‘As an Aboriginal man learning about fire in my own community and the cultural practices around that, how we burn for the culture of the land to support the country and plants and animals, is very important. We’ve been spending a bit of a time all over Australia looking for country which is really sick. Even if there are fire agencies in land management often they’re not burning in the right way for the country. We’re seeing what happens when you don’t burn the right way, you end up with a lot of fuel in the landscape and when you’ve got extreme conditions, like we have now, you’ve got huge fires.’ It’s common sense, you can’t have a fire without fuel. You try to start a fire without fuel and they go on about climate change; you’re kidding me! You can’t have a fire without fuel, but we’ve ignored all of that; he says indigenous knowledge of the land should be better utilised; that’s what you’ve said.

Jeremy: Fire management. So what happened is this variety of plant comes out of the rainforest and it’s got this unique ability to survive fire because of these epicormic buds hidden under the bark, and so that they actively cultivate fire, encourage it, because they know it will destroy the competition. They can survive but the competition can’t. But then there’s one other element missing: how did they get this fire? Lightning strikes are not going to happen enough, so aborigines have been here 40,000-60,000 years, and in that time they’ve adapted this fire management where they’re continually burning it off. They’ve kept the forests relatively open.

Alan: Hang on. We’ve created 15,000 national parks and you can’t get in. We locked the parks up. We lock up the fire trails. And here are these eucalypts, you’ve seen the pictures there; they survive, as you said, they survive—everything else dies. The whole floor where I’ve been is completely destroyed but the eucalypts are still standing. You have written: ‘this extraordinary affinity with fire means eucalypts have to be viewed as extremely dangerous incinerators that must be kept away from residential and commercial zones.’ I mean is it too late? They’re everywhere.

Graham: It is. I could sit here and start listing suburbs where they go right into the bush where the houses abut the forest and the forest is obviously going to be overwhelmingly eucalypt. I mean there might be other species occasionally but overwhelmingly eucalypt aren’t they?

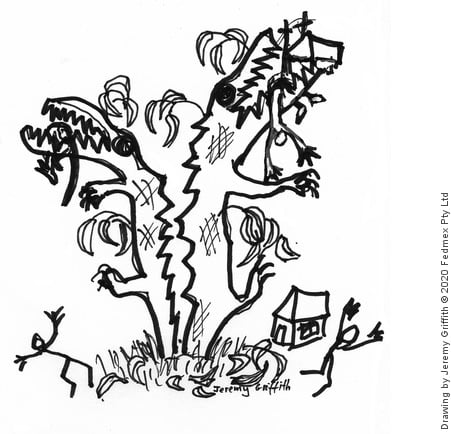

Alan: After the Canberra fires, when John Stanhope was the chief minister of the ACT, he said we’ve got to stop planting native plants because, as you said, they’re fire traps. Well, that was the end of John Stanhope! Don’t express such anti-religious views around here, but you have written a brilliant piece here—this man’s written this, Jeremy—‘greenies should take note. We have to view eucalypts as being like dangerous crocodiles planted tailed down ready to destroy lives and our world, with estimates of over a billion animals having been killed by this summer’s fires.’ And where are these people? There’s the crocodile. Jeremy did a little cartoon for his story, you see, there is the eucalypt and it is basically a crocodile in the forest and the forest is full of them.

Jeremy: I’m trying to get people to wake up here. We’ve got to wake up and realise just how dangerous they are. And then we can start thinking about how are we going to manage it. I mean non-eucalypt fires are bad enough, and destructive enough, but eucalypt forest fires are just so incredibly intense and ferocious and destructive. They are a whole different ballgame, and we’ve got to view them like that.

Graham: Let’s say you’re the you’re the Trump, you can do anything. You have absolute power over this. What would you do?

Jeremy: I would divide it—which is sort of what’s been done—to divide the east coast of Australia, the big endless forest of eucalypts, into big sections, into blocks, and with big clear areas between those blocks. I’d have beautifully managed and inserted fire trails right through them. They’re talking about having satellites being able to spot fires as soon as they emerge and then they have an immediate response from firefighters. So there is sectioned-off parts of the forest into contained, managed regions. And that’s sort of what got to happen. It just can’t be one endless forest.

And the other thing that I said earlier, and I think it’s going to be in the long term, because it’s an amazing one to think about it and face, is that we will even consider revegetating regions that are dominated by eucalypts with non-fire prone species.

Alan: Can I just interrupt you to make the point though that the horse has bolted. Now I’m just looking at figures here on national parks in Australia, and these are dominated, as you’ve written in your story, by eucalypts. New South Wales has seven million hectares of national parks. Seven million hectares. Victoria, 18 percent of Victoria is national parks; four million hectares. South Australia, 21 million hectares of national parks. Tasmania, 20 percent of Tasmania is national parks. What you’re saying is that dominated by eucalypts, I mean it’s an inferno waiting to overtake us.

Jeremy: Absolutely. Absolutely. Absolutely. And we’re just sitting there non-fussed as if there’s no threat there. Eucalypt forests are a wasteland; they’re basically a non-existent part of our continent because we can’t live near them, wildlife can’t live within them, it’s a suicide existence. Sooner or later a generation or two, they’ll get wiped out. I mean lyrebirds in the rain gullies, or swamp wallabies. I mean there was over a billion animals [killed in these bushfires].

Alan: They can’t move as quickly as the fire and the bird colonies have gone. You see this is the point, I mean basically it’s the combination, of course, of drought and you know there’s been no rain, and so on. But you bring that chemical combination together and you get what we’ve got; just you’ve said ‘the eucalypt forest fires are so frequent ferocious and destructive that humans can’t live near them and they’re in extremely dangerous habitat for wildlife’. You’ve said there’s got to be a complete change of mindset when thinking about eucalypts that recognise their true nature’. Out there they’re saying, ‘Oh, Scott Morrison, you’ve got to do more about climate change.’ Scott, tell them to go and jump. This is the issue. This is the man we’ve got to be talking to. And yet you’ve got national parks all over the countryside you can’t access and they’re dominated by eucalypts.

Graham: Would it be possible to manage all of these forests if we allowed more fire trials and all the rest of it and therefore we start to reduce the danger. Is that possible or not?

Alan: Well that would be a start.

Jeremy: I’m sure that all these fireys have been doing such an incredible job, and they’ve got a lot of experience. I was down trying to help a friend of mine, Tim Macarthy-Snape, look after his property and the fires got within two kilometres from destroying it. And I think they know what they want and I really do think that what they’d like is managed, sectioned-off parts. See that fire that came up the Nattai [national park] from the Warragamba Dam, that was going to come all the way up to [the town] Mittagong and take out Mittagong—there’s no break in between.

Alan: I’ve got one on top of my farm, I can tell you it’s still burning. Saturday is going to be a nightmare day if everyone down there is worried about Friday and Saturday. There was a dreadful fire last night in Canberra. The fire at [the town] Moruya hasn’t been put out. It’s extraordinary. You’ve said this, and we’ll end it here, ‘eucalypts were planted overseas with gusto’ and they are responsible for the fires in Portugal and Spain. And it’s not just Australia.

Graham: They’re everywhere in America.

Alan: Everywhere in America. And you’ve written, ‘eucalypts were planted overseas with gusto because they’re fast growing and have hard wood, but the world is starting to wake up to this crocodile in their midst’. And you quoted David Bowman, a forest ecologist at the University of Tasmania: ‘What the hell have humans done. We’ve spread a dangerous plant all over the world’. You’re a star, thank you for joining us.

Jeremy: Thank you for having me.

Alan: We’re listening. I hope someone else is. Hey, it’s a new experience to everyone watching, I’m sure. Jeremy Griffith, basically telling the story that has never been told.