Jeremy Griffith’s remarkable search

for the Tasmanian Tiger (thylacine)

In 1967 aged 21, Jeremy deferred his science degree at the University of New

England, and later that year hitchhiked to Tasmania with his dog Loaf, determined

to save the Thylacine—the Tasmanian Tiger—from extinction. The search was to total

some six years, with up to two of those years camped out in the field. In 1973, at the

completion of the most thorough search ever conducted for this extraordinary animal,

Jeremy was to reach the sad conclusion that the thylacine was indeed extinct.

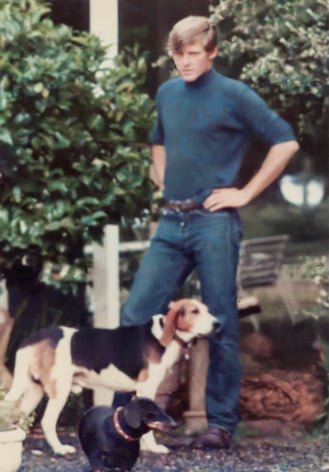

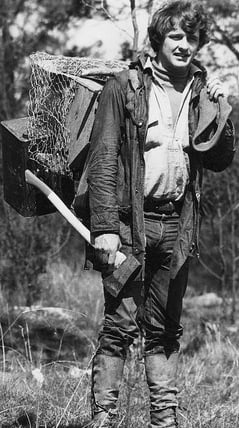

The day before Jeremy left the family farm ‘Box Point’ near Guyra in New South Wales for Tasmania

with his hound dog Loafy who he had trained to follow scent trails, determined to try to save the

Tasmanian Tiger from extinction. He had just turned 22. The family dachshund Othello is in the foreground.

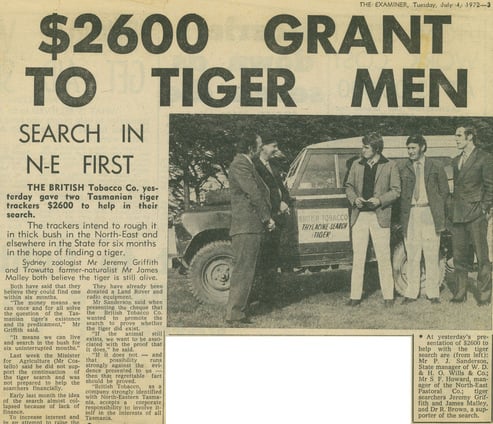

Fascinated by stories of the possible continued existence of the Thylacine in the wilds of Tasmania, Jeremy set off with only a trail bike to carry Loaf, his pack and himself. Armed with his enduring enthusiasm, initiative and ingenuity he began his investigation into the plight of this marsupial equivalent of the wolf. Jeremy raised the capital needed for the project through sponsorship, in particular from the British Tobacco Company and Ansett Airways. He also raised funds by working double shifts in a pea factory, and later in a tin mine.

By 1972 Jeremy and local dairy farmer and naturalist James Malley had attracted significant support and a Thylacine Research Centre was established in Launceston to generate interest, educate the community and log sightings which could then be investigated. Bob Brown, who was at the time pioneering the Australian Conservation Movement and was later to become a Federal Member of Parliament, donated his time and income for a year to support the Centre, which had two field units in operation and camera monitors that Jeremy invented in all likely wilderness areas.

2 minute video about Jeremy’s search for the Tasmanian Tiger

(taken from part 2 of the 2009 Introductory Video titled

‘The World Transformation Movement’)

34 minute 1973 feature documentary about Jeremy’s search for

the Tasmanian Tiger from A Big Country television series

(see details of this documentary below)

The Official Report Of The Search

The final Report of the search written in December 1972 by Jeremy, James Malley and Bob Brown, gives a thorough and enthralling account of their remarkable effort to save the thylacine from extinction. The Report is stored in the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston, under the custody of the curator of vertebrates, along with other files relating to the search. The search is also documented in a display at the National Museum Australia, and the first page of the report appears in the blog Finding thylacine on the Museum’s website.

Of Jeremy’s ‘uncompromising drive’ to save the thylacine, Bob Brown concludes in this report that ‘the future ease with which anyone shall be able to assess the thylacine’s history and survival states in full and clear perspective will be due to him’.

Jeremy’s search and findings have received

international scientific and popular media coverage

In November 1972, Jeremy was asked to prepare a paper for a symposium arranged by the Royal Society of Tasmania. The symposium was titled ‘The Lake Country of Tasmania’ and Jeremy’s paper, The Thylacine on the Central Plateau gives a factual account of the thylacine and its history and documents the search to date.

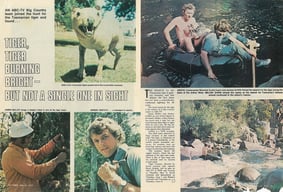

Also in November 1972 an ABC film crew came to Tasmania to film Jeremy’s search for their highly regarded documentary series A Big Country. The documentary, titled, ‘Tiger Country’, was aired throughout Australia in May and June 1973.

View the ‘Tiger Country’ Documentary

(see video included above)

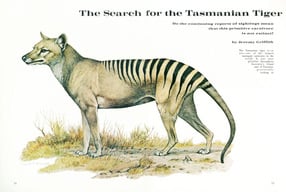

In December 1972, Natural History, the journal of the American Museum of Natural History, published an article written by Jeremy about his search for the tiger. The then director of the Taronga Zoological Park in Sydney and respected zoologist, Ronald Strahan, submitted the article on Jeremy’s behalf saying in a letter to the journal that despite a lack of funds ‘he has learned how to live off of the smell of an oil rag.’ The article generated widespread interest and helped raise the profile of this intriguing Australian marsupial predator and its plight.

View or print a PDF of Jeremy’s Natural History article (13 pages)

In February 1982 the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales published a book titled Carnivorous Marsupials. The book dedicates two chapters to the thylacine and references Jeremy’s six year search. It also contains thorough anatomical and behavioural descriptions of the animal.

View or print a PDF of the chapters on

the thylacine in Carnivorous Marsupials (24 pages)

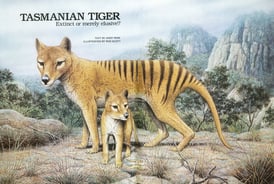

Following further attempts by other parties to locate evidence of the thylacine’s survival, Australian Geographic magazine published a feature article in its July-Sept 1986 edition titled ‘Tasmanian Tiger: Extinct or merely elusive?’, written by Andy Park. Jeremy was interviewed for the article and details of his search are documented. Jeremy states his belief that the tiger is extinct and explains, ‘It was my innocence that caught me out because I just couldn’t believe that so many people could be mistaken [in believing they’d seen it].’

View or print a PDF of the Australian Geographic magazine article (21 pages)

Many popular books about the thylacine citing Jeremy’s search have been published over the years including Tasmanian Tiger by David Owen, 2005 and The Last Tasmanian Tiger by Robert Paddle, 2013.

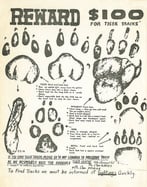

A 2019 exhibition at the Museum of New and Old Art (MoNA) in Tasmania, about memory, knowledge and attention, included a section on the thylacine and featured Jeremy’s footprint chart, reproduced in the exhibition’s hardcopy catalogue.

Throughout Jeremy’s six year search his efforts drew a lot of support, in particular from James Malley and Bob Brown, who appear on the right in this photograph. Bob of course went on to found and lead the Australian Green Party in Australian politics.

This is some rare black and white footage of ‘Benjamin’, the last known tiger who died in Tasmania’s Hobart Zoo in 1936.

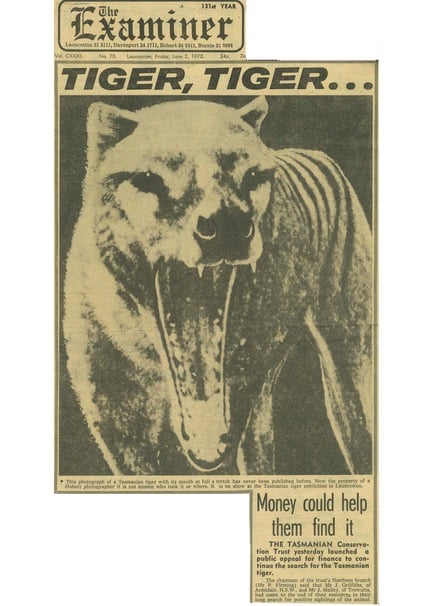

The Tasmanian Tiger is an extraordinary marsupial equivalent of the wolf. The tiger’s jaws were capable of this incredible gape.

Setting off with nothing but his own enthusiasm, initiative and ingenuity—as these next photos illustrate—Jeremy tried to rediscover and save the tiger from extinction.

The idealism of the unresigned mind

This piece was written by WTM founding member Genevieve Salter in consultation with Jeremy Griffith

In his part of The Official Report Of The Search that was included above, Jeremy explains his approach to his search for the Tiger, saying:

“My philosophy throughout was ‘what is best for the thylacine?’ It was what I called a ‘total approach’ and it has made decision making very easy for me.”

Jeremy’s selfless vision for what was a vital undertaking to try to preserve the thylacine reflects the selfless approach he has taken all his life to whatever problems he could see that needed to be solved. It is also evidence of his extreme idealism which the sheltered, soulful time he spent in Tasmania only served to accentuate. To those who have become part of the upset real world, reality is a self-evident state, but to innocence it is a complete mystery; why is everybody so upset—so angry and combative, so egocentric, competitive and selfish, so alienated and false and so unhappy?, is what utterly bewilders and preoccupies an innocent’s mind. What Jeremy learnt from his six year search was that our destruction of the tiger was a symptom of a much deeper problem. As he says of his first book Free: The End of The Human Condition, which he went on to spend 13 years writing, it ‘grew out of my desperate need to reconcile my extreme idealism with reality’ (Back cover of Free: The End of the Human Condition, Jeremy Griffith, 1988). Jeremy ultimately turned all his love and energy to the plight of the human species and he has worked tirelessly, day and night, since the early 1970s to bring biological understanding to the human condition.

Jeremy’s 1967-1968 document titled What I Reckon!, which he wrote when he was 21, further evidences the idealism with which he conducted his search for the Tiger. He carried this document, his earliest thinking about the human condition, everywhere he went during his tiger search years. So important was it to him that he memorised it and kept a small piece of paper with only the first words of each sentence to remind him.

In a biography Jeremy put together in 1994 he says:

The philosophy I had when I was 21 reveals the incredible mystery the exhausted, silent, dead world of reality was to me. The best explanation I could find for all the suffering, oppressiveness and unhappiness in the world given I was totally unaware of the alienated human condition was that it was due to the pressures of survival. The extent of my desperation with trying to understand the mystery of the numbness in the world can be deduced from how much I valued this explanation I had thought of for it. Another statement I often made in my younger days was that ‘people lived with a compromised frame of reference’. They seemed to not see the world honestly or truthfully. This was my early recognition of the resigned mind.

The World of an Unresigned Mind

(You can read much more about Resignation in FREEDOM: The End Of The Human Condition)

To understand Jeremy’s mind, in fact to understand all this thinking and behaviour, you only have to understand the position of the unresigned mind because that has been Jeremy’s life-long situation. For instance, to understand Jeremy’s What I Reckon! document, consider this wonderful description of the way the unresigned person sees the world from that masterpiece of American literature, J.D. Salinger’s 1945 novel The Catcher in the Rye, which is all about a 16-year-old boy struggling against having to resign to the dishonest world of denial of the issue of the human condition.

The boy, Holden Caulfield, felt ‘surrounded by phonies’ (p.12 of 192) and ‘morons’ who ‘never want to discuss anything’ (p.39), and spoke of living on the ‘opposite sides of the pole’ (p.13) to most people, where he ‘just didn’t like anything that was happening’ (p.152), to wanting to escape to ‘somewhere with a brook…[where] I could chop all our own wood in the winter time and all’ (p.119). The 16-year-old knows he is supposed to resign—in the novel he talks about being told that ‘Life being a game…you should play it according to the rules’ (p.7), and to feeling ‘so damn lonesome’ (pp.42 & 134). As a result of all this disenchantment with the world he keeps ‘failing’ (p.9) all his subjects at school and had to leave four schools for ‘making absolutely no effort at all’ (p.167). He says about his behaviour, ‘I swear to God I’m a madman [from the resigned world’s point of view]’ (p.121) and ‘I know. I’m very hard to talk to [because he doesn’t talk about the phony things resigned people speak about on the opposite side of the pole to where he’s living]’ (p.168).

Finally, the boy Holden found some rare honesty from an adult who spoke of men who ‘at some time or other in their lives, were looking for something [answers to why the world wasn’t ideal that] their own environment couldn’t supply them with…So they gave up looking [they resigned]…[adding] you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior’ (pp.169-170).

The book concludes with the 16-year-old Holden Caulfield dreaming of a time when Resignation will end, saying, ‘I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be’ (p.156). This time that Holden Caulfield so yearned for when we will be able to ‘catch’ all children before ‘they start to go over the cliff’ of Resignation to a life of utter dishonest, ‘phony’ superficiality and silence in terms of ‘never want[ing] to discuss anything’ truthfully again, now finally comes about with Jeremy’s finding of the all-clarifying, redeeming, relieving and rehabilitating truthful explanation of the human condition. The real ‘catcher in the rye’ is the ability to explain ‘human behavior’ so that it is no longer ‘sicken[ing]’ but understandable, and, best of all, healable.

What is so revealing about this description is how the resigned adult admits that ‘human behavior’ is presently ‘confus[ing]’ and ‘sicken[ing]’, it is a world where you are ‘surrounded by phonies’ and ‘morons’ who ‘gave up looking’ and now ‘never want to discuss anything’. As Jeremy frequently says, once you’re resigned and living in denial of the human condition, that superficial, dishonest, silent state is a self-evident state; you understand it and practice it, it’s no mystery at all, in which case it is hard to imagine what the world looks like when you are looking at it in an unresigned, honest way. For an innocent, unresigned mind it is incredibly bewildering and confusing, as it was for the unresigned Holden Caulfield. Everyone was behaving in the most fraudulent and non-ideal way, and yet no one was admitting it, or even acknowledging there was a problem. Because virtually all humans don’t experience a deeply nurtured, loving upbringing—because virtually all parents are variously upset and embattled by the human condition—virtually all humans have to eventually resign to living in denial of the human condition because when you’re not sound the human condition is an unbearably confronting, condemning and depressing subject. However, very, very occasionally a human does receive uncompromised, unconditional love in their upbringing, and these very rare few don’t have to resign to living in denial of the human condition. Instead they go on looking at the world truthfully, and behaving soundly, which puts them in the unresigned mental state—that the teenager Holden Caulfield was living in—for all of their life. These sound, unresigned, truthful thinking individuals are what we have historically referred to as prophets—they are rare individuals who behave securely and soundly and think in a denial-free, exceptionally honest and thus effective way.

It is hard for resigned minds to appreciate the way an unresigned mind views the world, but the story of Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye gives the resigned mind some access to the way the unresigned mind views the world. Given the bewilderment caused by the resigned world’s silence about the incredibly ‘sicken[ing]’ state of humanity, it’s not surprising that Jeremy had to find some way to explain the madness of it all, some framework of accountability, some way to reconcile his ideality with the all-pervading reality, which his What I Reckon! essay was his earliest attempt at producing. Jeremy was 21 years old when he wrote What I Reckon!, which is many years after the time when most people resign and stop viewing the world truthfully. It’s further evidence that Jeremy is an exceptionally rare unresigned thinker, and gives us some access to the journey that such thinkers have to go on.

The following is some correspondence that Jeremy had in 2025 with a young Australian who spends a lot of time in expeditions on the West Coast of Tasmania, some of it looking for the Thylacine

Jeremy: I love your initiatives and gear and your fascinated mind. I spent a few years back in the 1960s and 70s trying to rediscover and save the Thylacine from extinction and at one stage I went down the Arthur River in a tractor tube tracking the sandbars for any Thylacine tracks. I think it was you who made a video about the Thylacine in which you included a photo of me outside an old boiler on the White River near the Savage River. The ABC made a documentary about my search [see above]. Anyway you can see a lot about it at this link, www.humancondition.com/tasmanian-tiger-search. These days I’m writing books about the human condition of all subjects, which you can see a lot more about at this website, www.humancondition.com. Again, love your exploring spirit.

Anyway the horse has bolted wherever you look in terms of dysfunction, which is what I realised after trying to save the Thylacine from extinction. Someone had to go deeper and get to the bottom of the problem of our distressed-and-devastated-everywhere-you-look human condition, and being a biologist that’s what I’ve done.

Response: G’day Jeremy. Thanks for reaching out mate!

I’m actually very familiar with the ABC documentary yourself and James [local dairy farmer and naturalist James Malley] were a part of. It’s a fantastic documentary and a real credit the effort that you lads went to back then, to try to save the tiger. I have also done a few tiger inspired trips…so it’s an honour to hear you found me…thanks so much for reaching out. Your work has inspired me along the way so it’s great to see it come full circle!

Jeremy: Lovely to hear back from you. Yeah, love watching your adventures, long time since I was in that wild country.

My close friend and supporter of my work, the first Aussie to climb Everest, Tim Macartney-Snape, has taken me out into the western desert of Western Australia, but there’s no Bauera [a wiry shrub that makes walking extremely difficult] out there! James and I actually found the remnants of an aboriginal settlement down on the south-west coast, I think maybe but I’m not at all sure that it was at the mouth of the XXX River. We told Bob Green at the Launceston Museum about it so they have the details, but he said not to publicise it because he couldn’t protect the site. I often wonder if any of those west-coast early miners’ and explorers’ articles you research report seeing tigers. I’ve just finished another book and potential video about the fu*king human condition. Stay bold and out there Mr Boys Own Adventure Man!

P.S. I once invented a fold-up alluvial gold mining contraption a person could carry into the bush, so, like you, I’ve been fascinated with prospecting.

The thing is a big predator like the Thylacine needs a reasonably big territory so there really isn’t any chance of a viable population of them surviving undetected out there. The Takahē bird was rediscovered in a remote part of the south island of NZ, but it isn’t a predator that has to range a pretty big area. And I invented what was really the first trail camera in the world, which you can see in that ABC documentary, and had them monitoring pretty well all the possible remote areas down there and they didn’t find any Thylacines. With regard to the south-west, as you know that is often such leached and glaciated morainal poor soil that any Thylacine there would very likely be living along the coast preying on the wallabies that have migrated there to live off the marram grass food there, and I tracked all the coast north of Macquarie Harbour, and James and I tracked all the coast south of Macquarie Harbour without finding any signs of Thylacines—we even tracked a wild dog that cray-fishermen told us they occasionally saw on the south coast, so we don’t think we were missing much. And god, we investigated so many fu*king sightings and accounted for many of them as being probably tiger cats which can get pretty big and impressive and when you quiz people they can’t actually remember whether it was stripes or spots that they saw, stuff like that over and over again. I write all the time about the human condition, which at base is humans’ incredible insecurity of self and resulting capacity for extraordinarily wishful and deluded thinking. Anyway, it’s excruciatingly sad, but I know from heaps of first-hand experience and in the field research that they’re extinct. Fu*k it, I hate it to the bottom of my toes that the tiger is no longer with us, but that’s why I work so hard on fixing the real problem us fu*ked up humans had to fix, which is the human fu*king condition, you really should have a look at this human condition stuff, even just watch the one-hour interview I did which is at the top of our website.

See also Jeremy Griffith’s artwork and Jeremy's Griffith Tablecraft furniture.

For insights into Jeremy’s ability to grapple with and solve the human condition,

see Freedom Essays 49 to 51.