The fall of a mountaineer

Having climbed Everest twice, Tim Macartney-Snape

thought he had faced his ultimate test. He was wrong.

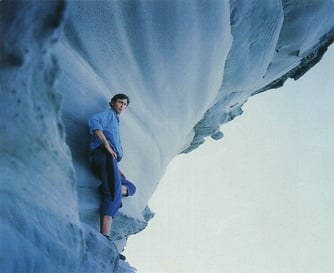

Tim Macartney-Snape: ‘There are even higher

mountains, deeper gorges, more frightening terrain

inside our heads than in the physical world.’

Rape is the metaphor elite mountaineer Tim Macartney-Snape uses to describe what happened to him three years ago when ABC television’s Four Corners portrayed him as the possibly deluded disciple of a virtually unknown philosopher, Jeremy Griffith [in fact a significant number of eminent scientists and philosophers in the world have written impressive commendations for the work of Jeremy Griffith - TM-S]. More than that, it said he used his position as a national hero - he has climbed Mt Everest twice - and popular school speech night guest to recruit young people to Griffith’s Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood [FHA], traumatising their families and jeopardising their future.

The foundation’s teachings came across as bizarre, and Griffith himself as obsessed, cutting an alarming and excitable figure. The foundation complained to the Australian Broadcasting Authority [ABA] soon after the program went to air. In February this year the ABA found heavily against Four Corners, saying the program was unbalanced because it left out relevant viewpoints about the issue of family turmoil; inaccurately reported the merit of Griffith’s work [the program’s presentation of the merit of Griffith’s work was originally found to be inaccurate by the ABA but later a breach wasn’t found on this issue - TM-S]; alleged inaccurately that Griffith saw himself as a figure equivalent in stature and eminence to Jesus Christ; and failed to give relevant viewpoints about Macartney-Snape’s role as a guest speaker. The latest word is the ABC may challenge the ruling. [In late May the ABC told the ABA that they are not going to challenge the ruling. On the 10th July the ABA wrote to the ABC asking them to apologise to the FHA. To date the ABC have not apologised, and the FHA has been told by media experts that it is typical of the ABC these days to not apologise to those they have aggrieved. The FHA has written to the ABC describing this culture as ‘arrogant’ and ‘dysfunctional’. - TM-S]

Contacted by The Australian Magazine about a month prior to the finding, Macartney-Snape was keen no profile of him should appear before the ABA report: “You could liken this to a situation where a woman claims she has been raped and there is an inquiry into it and until that inquiry puts forward its findings [there is a question over]...whether or not the claims...are true.” It was a confronting allusion, given what he was really trying to say was simply that mud sticks.

So a first impression of Macartney-Snape is as a victim, a voice on the phone, hesitant and wary, negotiating rules of engagement. Distinctly at odds with everything read about or seen of him, in which he had seemed a true and confident adventurer, open and assured.

After the program went to air, Macartney-Snape’s income, on his own estimate, fell from $55,000-$60,000 to between $10,000 and $15,000, as corporate speaking engagements dried up. So did invitations to address schools and service clubs, for which he makes no charge. It cemented his estrangements from millionaire businessman Dick Smith, who had been a staunch backer, and from his friend Howard Whelan who, with wife Rosie, gave an interview to Four Corners about the apparently insidious nature of the Griffith’s philosophy and practice.

The aggrieved parents in the Four Corners report, of which only one set went on air, believed adherents were prioritising their commitment to the foundation at the expense of other relationships and activities. Macartney-Snape points out there were only five people whose parents - he calls them “the irate fathers” - felt that way, in contrast to the 30 or so who signed a letter in support of the foundation and the effect its work was having on their children.

Whelan appeared as a disgruntled spouse (his wife used to work for the foundation) but his credibility was apparently enhanced because of his long association with Macartney-Snape, both personally and as editor of Australian Geographic, the magazine set up by Smith in 1985, published by the Australian Geographic Society. The society sponsored Macartney-Snape’s second ascent of Everest in 1990, dubbed “Sea to Summit”, which began on the coast in the Bay of Bengal, and from which a book and film of that name were produced.

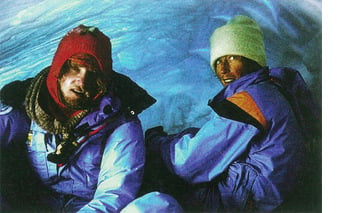

Smith and his family had been trekking with Macartney-Snape in the past and spent time at base camp with him and his then wife, Dr Ann Ward. In 1990 the foundation was already a bone of contention between Smith and his protege; nevertheless its flag was carried to the summit along with the Australian, Nepalese and Australian Geographic flags, and the book, peppered with references to the philosophy, contains a potted version of it in an appendix.

By the time the journey was over, Macartney-Snape’s marriage was in strife. He records in his book Ward’s ill-concealed anxiety about her husband of less than a year tackling the world’s tallest peak alone and without oxygen, after walking more than 1000km to get to its base. He was clearly disappointed at what he construed as her lack of faith, that he would “do something silly and get himself killed”. Further pressure was applied when the issue of children arose, and the couple split at the beginning of 1992. Looking back, he says, it was rash to get married in the same year he dissolved his business partnership with Steve Colman (in trekking company Wilderness Expeditions) as well as selling up with his family in Victoria to buy 16ha in the southern highlands of NSW.

As 1995 wore on, without much work or public reputation, the man twice honoured with Orders of Australia had plenty of time to contemplate the wisdom of his decision. “It was devastating,” Macartney-Snape says of the effect of the television program. “I was basically living hand to mouth. Still am.”

Writer and climber Lincoln Hall, a close friend since university days, went from his Blue Mountains home down to see him soon after the program aired, and recalls how dark those days were. “Tim and I went climbing,” he says. “He said if he had not survived all that he had been through in the mountains this probably would have destroyed him.”

Colman, another mate from university days as well as his ex-business partner, says Macartney-Snape went from introspective to introverted, but adds, “A lot of this is washed off both by where he lives, in the bush, and by spending time in the mountains, which are his spiritual heartland.”

These days Colman is a leadership consultant with his own company, Global Learning. He and Macartney-Snape had shared a platform many times before corporate audiences. “I actually find myself defending him in my sort of work...they would query me about it as if he had lost the plot,” he says.

According to Macartney-Snape, the report followed attempts to talk him out of his commitment to the foundation. He says former mentor Smith had asked him to see a deprogrammer, the irate fathers lectured him about his responsibility to be a good example to their children, and rumours had been circulated about his personal life.

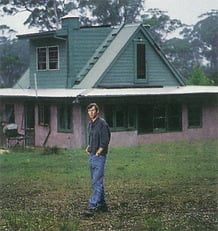

Detailing these events, Macartney-Snape, now 42, is mostly dispassionate, apart from an occasional grim tone, ironic laugh and mildly emphatic word. He seems sad, hurt and indignant. In the aftermath of Four Corners, he built his sturdy wooden house, low-set and comfortable, a stone’s throw from where his mother now lives and where his three sisters stay when they are in Australia.

On the day The Australian Magazine interviewed him for the first time, his partner, Stacy Rodger, was busily establishing a garden bed at the back, supervised on and off by the four dogs. Tweedie the ancient labrador and Honey the blue heeler followed as Macartney-Snape set off through the bush carrying chairs and coats (against a fresh breeze), towards a clearing where a fire was waiting to be lit. It was 9am on a Sunday and the conversation was going to take place on his ground.

At 187cm (6ft 3 inches) and 72kg he is a thin giant with a sensitive, freckled face and fly-away hair. The question “why climb?” is quickly part-answered by his physique, which seems custom-designed to find toe and fingerholds in crevices, and with spider-like stretches to work up surfaces and slopes impossible for those of more ordinary dimensions. Macartney-Snape sat down, disposing himself with remarkable grace, tucked one leg under the other and thereafter spent a lot of time holding the proffered paw of the labrador sprawled at his feet.

Up to the moment Four Corners went to air, his life had been a succession of victories as his childhood passion for “getting to the top of the hill and seeing what was on the other side” found expression in ever more complex and demanding forays into mountain wilderness. He has described the allure thus: “The extreme, potentially life-threatening situations of this kind of frontier battle employ to the full faculties that lie wasted, and unearth qualities that lie dormant in normal life. You develop an intensity of perception that tinges every experience with a feeling of magic.”

Up to the moment Four Corners went to air, Tim’s life

had been a succession of victories as his childhood passion

for getting to the top of the hill found expression.

That he should be at home with that is understandable, given he was born in a magic land, Africa, and partly raised there in southern Tanzania, then known as Tanganyika, on a farm 140km from the nearest town, with no radio, telephone or electricity. He fell out of trees and became confident operating in isolated environments. Packed off to boarding school in the north of the country when he was eight, he learned his lessons within sight of the 4500m volcano Mt Meru and, close by, Mt Kilimanjaro.

His Australian father, Jack, 60 when Macartney-Snape was born, brought the family to rural Victoria in 1967, when his sight began to fail and the troubles which followed Tanzanian independence began to mount. Macartney-Snape concedes his father was a maverick who survived a ruptured aorta at the Battle of the Somme by being in the right place at the right moment: next to a medical post and close enough to someone else with the same blood group for a just-in-time transfusion. He became an organic farmer in Africa in the twenties after a plan to go gold prospecting in Papua New Guinea was shelved. “I think he was quite proud that I had the right sort of qualities he would have liked in a son: I could discipline myself and I was obviously fairly tough, therefore I could probably do all right in life; I could make do,” Macartney-Snape says.

Jack died in 1978, six years before his son climbed Everest for the first time. By then, Macartney-Snape had had the benefit of a discount private education at Geelong Grammar, offered because of the family’s long association with the school. He turned from enthusiast hiker to devotee climber as his bushcraft improved and chose to study biology at the Australian National University to be closer to the Snowy Mountains. Lincoln Hall remembers him as “fairly unassuming”, being known as the “Minister for High Alpine Transport” because of his bush skills. “People are amazed when they meet him for the first time - with his Prince Charles ears and Twiggy legs - but what a lot of people don’t see because it’s not on display is his extraordinary drive,” Hall says.

In 1978 he reached the 7000m summit of Dunagiri, his first Himalayan peak, with Hall. Everest didn’t even rate as a dream. “I thought it was not a climber’s mountain; it was just a mountain people climb to become famous. I wasn’t into that.” He laughs at his youthful snobbery. His feelings changed in 1981, when he climbed the 6800m Ama Dablam, south of Everest, which meant spending a couple of months with the bigger mountain just over his shoulder. “Seeing Everest and experiencing how progressively difficult [climbing is] as you get to altitude, I thought it would be a hell of an experience and especially if we were to do it by the so-called fairer means of not using oxygen and not using a big back-up team of Sherpas.”

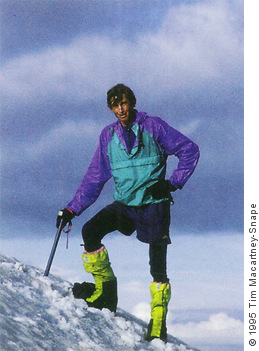

Macartney-Snape and Greg Mortimer became the first Australians to climb Everest, on October 3, 1984, and they did do it without oxygen, which magnified the achievement considerably. Macartney-Snape had been making a living guiding treks to fund his serious climbs since 1980. Highlights of the next decade were 7300m Trisul (which he didn’t summit) and 7960m Annapurna II in the Himalayas; Gasherbrum IV, also just under 8000m, in the Karakoram Range in Pakistan; and 6000m Anyemaqen in China. A planned attempt on K2 (the world’s second-highest peak at 8610m) in 1987 was aborted because of foul weather.

The extremity of the conditions on these climbs is enough to give ordinary earthbound mortals nightmares. At 5000m breathing becomes difficult and anything beyond that involves risks that can only sometimes be calculated. Cerebral and pulmonary oedema, frostbite and hypothermia are common. Macartney-Snape’s ability to perform at such heights (Everest is 8848m) is probably a combination of his low weight and big lung capacity, as well as his tenacity, skill and fitness.

Somewhere in this period - particularly after the 1984 ascent of Everest - Macartney-Snape became well known. He began dealing with the media on a regular basis, and honed writing and speaking skills. Painfully aware he had failed matriculation English the first time he sat for it, he knows he is no Hemingway. Nevertheless, he writes with honesty and occasional eloquence about climbing and about India in his book, Everest From Sea to Summit.

IT IS CLEAR THE MANY JOURNEYS THROUGH UNTRAMMELLED territory, encounters with indigenous people and in particular with the Sherpas, together with near-death experiences in unimaginably beautiful and terrible places set him thinking about the human condition. Depending on your point of view, this is where Macartney-Snape, Everest hero, begins the transformation to nutter.

“Definitely one of the aims of the expedition was to give me a better opportunity to help Jeremy [Griffith],” he says of the 1990 adventure. In 1987 Smith had introduced him to Griffith, a creator and maker of designer wooden furniture. As the two got talking, Macartney-Snape was taken by Griffith’s ideas. “I think the reason he managed to get across to me is that he totally and utterly lives for getting to the bottom of things,” he says.

Thus the philosopher acquired a priceless asset: a bona fide celebrity keen to learn and spread the word. After the second Everest climb it was clear things could not go on as they had been. For one thing there were, in effect, no more mountains left to climb, although Macartney-Snape is impatient of the view that after Everest all else is an anti-climax. “Not at all,” he says. “It just gives you more confidence that you can do what you want to do and it opens up new horizons. As far as climbing is concerned there are a million things one can do to push the barriers of what’s possible.”

Hall agrees there was an Everest “effect”. “He felt very strong and that he could go on and climb anything,” he says. “Then he got involved in the foundation and it took his energy in a different direction.”

Macartney-Snape was also very wary of being trapped, as some other brilliant adventurers are, into seeing no other bearable future than pitting themselves against worse and worse odds, a losing battle for an ageing body, no matter how experienced in the wilderness or inured to its hardships.

In short, he stopped focusing on the next mountain and began to conceive of a life built around exploring humanity and its future. “I suppose as I’ve grown up I’ve come to realise for those who are fortunate there are responsibilities,” he says. “Y’know I’d love to be out in the Snowy Mountains all the time, but I just feel that at the end of my life if I looked back and saw that there was an opportunity there for me to make a difference and I didn’t take it, that I would have wasted my life.

“There are even higher mountains, deeper gorges, more frightening terrain inside our heads than there are out there in the physical world. It’s a matter of shifting focus from the unreal arena to the real one-and it’s actually the opposite of what you first think. Although it’s real out there in the physical sense, in terms of the journey what’s really happening is inside and the exploration that has to be done is inside.”

Colman confirms this: “The physical risk is less challenge than the psychological/ emotional risk he’s now engaged in.”

On a more prosaic level, Macartney-Snape had counted on a living as public speaker, as well as guiding treks and eventually reaping some reward for a small investment in an outdoor clothing company in Perth. Spreading the foundation’s word was imperative and together with Griffith and other senior members of the group he had mapped out a strategy involving newsletters, meetings and courses. Significantly, it did not include open “sales pitches” at school functions. Macartney-Snape says he can recall three occasions on which he mentioned Griffith or the foundation in such settings. One was at Geelong Grammar, of which Griffith is also an old boy; one was at a school in Albury, Griffith’s hometown; and the third was at Concord High School in Sydney, at the express request of Four Corners, so it could be filmed. By the time he left on a private trip to climb Cerro Sarmiento in Tierra del Fuego in April 1995, he feared the program would be negative.

Part of Macartney-Snape’s talent has always been devising and carrying through controlled responses in tight spots. It has kept him alive on the edges of crevasses, in storms and through icy strandings. As he talks about what he calls the Four Corners “saga”, the unspoken thought behind many sentences is “how could I have planned this better? Anticipated disaster? Managed the fallout?”

“Tim excels at giving his utmost and I think the thing about the Four Corners thing is that there is no utmost to give,” says Hall, explaining the difficulty of grappling with an abstract enemy. “It’s completely out of his control…what that’s done to him I don’t know.”

AT MACARTNEY-SNAPE’S SECOND MEETING WITH THE Australian Magazine - indoors ensconced in sofas arranged around a fireplace with a mantelpiece covered in photos and bric-a-brac - he is more relaxed. What had at first seemed like a possibly characteristic anxiety is revealed to have been mere nerves. The dogs are outside, and it is he who is sprawled, in casual leather loafers, longish khaki shorts and a collarless blue and white cotton shirt.

He manages to laugh over the fact that his most recent speaking engagement has been for World Expeditions, where he works. “I’m reduced to giving talks to mates,” he says, ruefully. Constraint gone, it seems an ideal moment to ask how depressed he was after the Four Corners program went to air.

Looking back, he says, it took some time for the enormity of the damage to his reputation to sink in. Although expert in the complicated science of unknown territory, this first big challenge of his new life at first left him battered and subdued. “When I saw it [the program] I thought, ‘oh well, it could have been worse’. And then after a couple of weeks I started to think, ‘Jesus, that was bad, you know,’ and as time went on it began to sink in just how damaging it was. I’m angry with myself that I wasn’t more angry. I suppose it’s to my detriment in many ways that I have a very forgiving nature.”

It is a classic description of shock, and in its wake comes a kind of half-revelation, that he felt let down by some of those from whom he might have expected support. “Maybe it’s my own fault, that I haven’t sort of stood them up and said, ‘You should realise what those guys have done.’ ”

Macartney-Snape at home with two of his dogs.

His former business partner says he went

from introspective to introverted after the

airing of the Four Corners program

Colman, however, has seen no real signs of anger. “I take my hat off to him - I’m angry,” he says. “I have found it really disappointing that someone who had achieved so much was harmed so much. I was disappointed that people who I thought were quite close to Tim abandoned him a bit.”

And he sees the loss of Macartney-Snape from the corporate world as a serious one. “A lot of people who have had the unique experience of being with Tim in a small group setting talking about Everest and spending some time with him in the mountains have got significant benefit from it,” Colman says.

It was a stunning blow for the erstwhile media darling. If he ever lacked awareness about the deal with the devil made by people who allow themselves to become public figures, he is alive to all its difficulties now. The young man who needed television, radio and press interest to get climbs funded is now a wary operator whose calculations about such things have become fiendishly complicated by full knowledge of the price the unguarded pay. Although it hardly seems possible, he asserts: “I knew what I was putting on the line.”

The public disapproval and revulsion when someone of apparent good sense appears to do something flaky was compounded when it seemed Macartney-Snape had broken taboo of preying on young minds by indoctrinating them with the foundation’s beliefs. This was so particularly given the foundation’s view it is mostly young people who are open to the information it is offering; older ones being too set in their ways.

“Me being involved would just add substance, add kudos, add respect to the foundation, there’s no doubt about that,” Macartney-Snape says. He sees himself in the tradition of Thomas Huxley, 19th century biologist and champion of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

MACARTNEY-SNAPE’S LEGENDARY COOL HEAD WILL NEED TO serve him well as he works to reconstruct his reputation, and searches for the least threatening way possible to generate interest in the foundation’s work. Recently, in an attempt to publicise it once more, he mailed out to 90 opinion leaders an essay and a covering letter about the foundation’s philosophy. All he wants, Macartney-Snape says, is a hearing for the ideas, a debate about their validity.

The ramifications of the Four Corners program became an important test of his philosophy, which emphasises controlling the fundamentally competitive and destructive male ego always wanting to score goals (climb mountains) and generally make its presence felt. Asked for an example of a challenge to his own ego he says: “I suppose one, although it was much milder than it might have been, is the sort of damage my reputation suffered from Four Corners, not being able to earn a better living, all that sort of thing.

[Note: Jill Rowbotham’s emphasis here on ‘controlling’ the ego needs correction. The work the FHA supports brings reconciling understanding to the human condition. It explains why we humans have not been ideally behaved. It dignifies humans, resolves the underlying insecurity in our makeup. The effect of digesting the understanding therefore is that the egocentricity in human nature subsides. It is a natural effect, not some enforced or manufactured restraint of ego. Most significantly, ‘control’ is not needed. Control is what we humans had to use when we lacked the ability to understand ourselves. Reconciliation of the human condition means that humans will naturally change from being egocentric, or preoccupied asserting self-worth, or selfish, to being ego-satisfied, and thus no longer selfishly preoccupied - TM-S.]

“I’m not going to say it was an easy time, it was certainly tough and I guess no-one likes to be viewed as being a weirdo. Someone once asked me what I feared most and I came up with ‘being misunderstood’.”

‘I guess no-one likes to be viewed as being a weirdo.

Someone asked me what I feared most

and I came up with “being misunderstood”.’

So, how does it feel to have confronted the worst? ‘It makes life harder, there’s no doubt about it…but you have to do what you think is right and stick to it.”

And has his philosophy steered him away from seeking wealth and fame? “Yes, that’s not as important to me now as it was.” So it was important once? “Oh yeah, there was a tendency there, for sure.”

So he bought the “fame thing”? “Yeah, definitely.”

Hall’s reflections on fame are interesting in this context, given he climbed almost to the top of Everest with Macartney-Snape in 1984 but turned back before the summit.

“I think the best thing that ever happened to me was not getting there,” Hall says. “The ramifications were that I was not a hero and everyone else was. Being a hero is a drag and I realise now Tim was a victim of that and everyone thought he had the answers because he had climbed Everest.”

It’s been a long time since Macartney-Snape climbed a big mountain, although such peaks are often on his mind, judging by the frequent references to that imagery. He is tough-minded and unsentimental about it. “Although I cannot get rid of it, it actually is a sort of delusion, this desire to look over the horizon. You should be, I suppose I could be content with the borders of where I live because there is an equal if not greater degree of exploration to be done within your home environment-in your head-than there is out there.”

He adds: “But the experiences I have had climbing have certainly been good training: I could not have set myself up in a better way, really. When your life is on the line and you are having to deal constantly for days on end with decisions which dictate whether you live or die, it puts other problems in life into perspective and makes you realise that what people think are really big problems are not really big problems.”

Asked if there is a mountain he wants to climb, he says: “Not with the passion I had, no there isn’t. So I suppose in that way I have changed. It’s such a demanding environment on a big mountain that unless you 110 per cent want to be there, are driven to it…it’s much more dangerous if you are not really, really wanting to be there and focused.”

Yet, when pressed, some of the desire remains, and is specifically directed. His hands trace in the air a mountain, Annapurna IV, about 7000m. Not a tough climb from the north side, but hard indeed from the south, where it can only be scaled by starting from its base, set in the subtropical plain. His fingers indicate a route to the top and the explanation flows until, remembering his listener, he pulls himself up with a jolt to ask: “Have you been to Nepal?”

At The Foundation

The Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood was established in 1988 [actually 1983 - T-MS] by Jeremy Griffith, who has a science degree (zoology major) and spent five years searching for the Tasmanian Tiger (now believed to be extinct) before establishing a successful furniture design and manufacturing business with his brother. He sold his half of the business to his brother in 1991 for $2 million.

Since 1975 he has worked on the ideas the foundation promotes. It holds that the human condition - the paradox of how individuals can be so good and so bad - is explicable in terms of evolution. When humans developed a self-conscious mind they began to act contrary to their cooperative instinct and this set up conflict which they have lived with ever since. Hence the psychological trauma which plays itself out in violence, selfishness, competitiveness and other ego-driven behaviour.

Coping mechanisms include religions and philosophies. The good news, the foundation says, is that now humans are sufficiently evolved to understand how this happened, and can work towards their destiny, which is to return voluntarily to their original cooperative state, acting for the communal good. The bad news? Time is running out because people may end up too “psychologically buggered”, as Tim Macartney-Snape says, to do anything about it.

While the outcome of these ideas - selflessness - seems innocuous enough, Macartney-Snape insists that applying biological explanations has implications for the way the whole of society functions and is deeply challenging to most people because it supersedes all existing beliefs and creeds, including Christianity.

Griffith’s book, Beyond the Human Condition, published by the foundation in 1991 with a foreword by Macartney-Snape, sets out his ideas. The traumatised state in which humanity currently exists is characterised as “upset”; the kind of thinking that is reluctant to face the threatening truths about ourselves is referred to as “evasive”.

The foundation on human personality: “Since our various personalities are in the main our various states of upset, in the upset-free future we will all have similar personalities.”

On who runs the world: “Now that the largely male-dominated battle to champion the intellect or ego is won, we can return to a matriarchal (female-dominated) world where nurturing or love is all important.”

On politics: “There is no longer a left and right wing in politics, only a new form of left wing, completely free of pseudo-idealism.”

On revolution: “Revolution is not necessary. All we need to do to overcome resistance and suffering is spread the understanding.”

On cities: “The truth is cities were not functional centres as we evasively claimed, they were hideouts for alienation and places that perpetuated/ bred alienation. We will begin to close our cities down.”

The goal: “We can now repair and then savour the world.”

The number of people actively involved with the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood sits at about 100, with more than half aged between 20 and 30 [and the balance are over 30 - there are no members under 21 and no member became involved while they were at school, apart from 5 who were introduced to the FHA through older siblings or close family friends involved in the FHA - TM-S]. ---

Jill Rowbotham

[Important Correction: Again, Jill Rowbotham’s comment that understanding the human condition means people ‘return voluntarily’ to a cooperative state needs correction. Understanding the human condition resolves the dilemma that was the source of our egocentric natures. The understanding subsides our competitiveness, egocentricity and alienation and by so doing removes the need for self-control.

This is why religions, and other self-management strategies, where we ‘voluntarily’ chose to self-control our upset human natures are ‘superseded’ when understanding of our upset natures arrives. With biological understanding of why we humans became ‘upset’, the upset itself is dissolved, leaving no upset to be controlled. Of course the digestion of the understanding and resulting subsidence of our species’ historic upset is a process that takes time.

The difficulty with the arrival of understanding of the human condition is that it raises issues we humans have traditionally coped with by evading and blocking out from our mind. While the truth about ourselves has been made compassionate our historic fear of the truth about ourselves makes it difficult for us to access the liberating knowledge. This was the point I was making to Jill when I talked about the danger of humans being too ‘psychologically buggered’ now to confront the truth about ourselves.- TM-S.]