The following two-page feature story about Jeremy Griffith (/jeremygriffith) and the

FHA (now WTM) appeared in the 21 April 1998 edition of The Bulletin,

incorporating Newsweek, a national weekly magazine in Australia.

Story by Lenore Nicklin

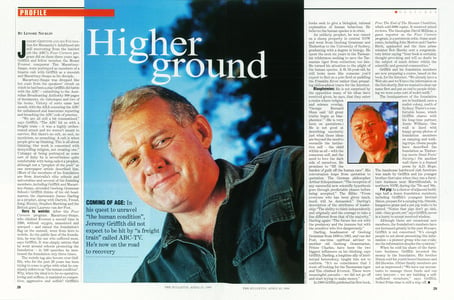

Higher Ground

COMING OF AGE : In his quest to unravel “the human condition”, Jeremy Griffith did not expect to be hit by “a freight train” called ABC-TV. He’s now on the road to recovery.

Jeremy Griffith and his Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood are still recovering from the hatchet job the ABC’s Four Corners program did on them three years ago. Griffith and fellow member, the Mount Everest conqueror Tim Macartney-Snape, were portrayed as members of a bizarre cυlt with Griffith as a messiah and Macartney-Snape as his disciple.

Macartney-Snape was dropped like hot coals from the speakers’ circuit on which he had been a star. Griffith did battle with the ABC – submitting to the Australian Broadcasting Authority 900 pages of documents, six videotapes and two of his books. Victory of sorts came last month, with the ABA censuring the ABC for unbalanced and inaccurate reporting and breaching the ABC code of practice.

“We are still a bit traumatised,” says Griffith. “The ABC hit us with a freight train—it was a highly orchestrated attack and we weren’t meant to survive. But there’s no cυlt, no sect, no mysticism, no preaching. A cυlt is when people give up thinking. This is all about thinking. Our work is concerned with demystifying religion, not creating one.” Unhappy at being portrayed as some sort of deity he is nevertheless quite comfortable with being called a prophet, although not a “prophet of the posh” as one newspaper article described him. (Most of the members of his foundation are from Australia’s elite schools and universities and several of the founding members, including Griffith and Macartney-Snape, attended Geelong Grammar School.) Griffith thinks of his old headmaster, the charismatic James Darling as a prophet, along with Darwin, Freud, Jung, Huxley, Stephen Hawking and the British guru Laurens van der Post.

Hero to weirdo: After the Four Corners program Macartney-Snape, who climbed Everest a second time in 1990, without oxygen, unassisted and unroped—and raised the foundation’s flag on the summit, went from hero to weirdo. As the public face of the foundation, he was the one who suffered most, says Griffith. It was simply untrue that he went around schools promoting the foundation—in 100 speeches he mentioned the foundation only three times.

The weirdo tag also hovers over Griffith, who for the past 20 years has been trying to come to grips with what he constantly refers to as “the human condition”. Why, when the ideal is to be co-operative, loving and selfless, is mankind so competitive, aggressive and selfish? Griffith’s books seek to give a biological, rational explanation of human behaviour. He believes the human species is in crisis.

An unlikely prophet, he was raised on a sheep property in central NSW and went from Geelong Grammar and Timbertop to the University of Sydney, graduating with a degree in biology. He spent the next six years in the Tasmanian wilderness seeking to save the Tasmanian tiger from extinction; too late. He turned his attention to the plight of the human species. A fit 53-year-old, he still looks more like someone you’d expect to find on a polo field or paddling the Franklin River rather than preparing philosophical tracts for the Internet.

Blasphemies: He is not surprised by the opposition many of his ideas have received given, he says, that they enter a realm where religion and science overlap. “George Bernard Shaw said ‘All great truths begin as blasphemies’.” (He is very keen on quotations.) He is not good at describing succinctly just what those ideas are beyond the need to reconcile the instinctive self—the child within us all—with the conscious self, and the need to love the dark side of ourselves. He promises to “lift the burden of guilt off the human race”. His conversation leaps from quotation to quotation. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: “The reception of any successful new scientific hypothesis goes through predictable phases before being accepted.” The Bible: “From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded.” Darling’s description of the attributes of leadership: “The ability to think independently and originally and the courage to take a line different from that of the majority.” Darling again: “The future lies not with the predatory and the immune but with the sensitive who live dangerously.”

Darling, headmaster of Geelong Grammar from 1930 to 1961, and van der Post, one-time spiritual adviser to another old Geelong Grammarian, Prince Charles, have been the two biggest influences on his thinking, says Griffith. Darling, a longtime ally of intellectual heterodoxy, taught him not to conform. “It’s no coincidence that I went off looking for the Tasmanian tiger and Tim climbed Everest. These were meaningful pursuits—we did not go off and start trying to make money.”

In 1988 Griffith published his first book, Free: The End of The Human Condition, which sold 6000 copies. It received mixed reviews. The theologian David Millikan, a guest reporter on the Four Corners program, is a persistent critic. Some academics, including John Morton and Charles Birch, applauded and the then prime minister Bob Hawke sent a congratulatory letter saying “Your book is certainly thought-provoking and will no doubt be the subject of much debate within the scientific and general communities.”

Griffith and his foundation members are now preparing a course, based on the book, for the Internet. “We already have a website and we’ll have the information on the Net shortly. But we wanted to clear our name first and put an end to people thinking we were some sort of weird outfit.”

The headquarters of the foundation are in bushland, once a nudist colony, north of Sydney. There’s a comfortable house, which Griffith shares with his long-time partner, Annie Williams. One wall is lined with happy group photos of foundation members on camping and walking trips. (Some people have described the foundation as Timbertop meets Dead Poets’ Society.) On another wall there is a framed poem by A.D. Hope. The handsome hardwood slab furniture was made by Griffith and his younger brother Gervaise when they ran a furniture business near Murwillumbah, in northern NSW, during the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Pet pig: In a cluster of adjacent buildings half a dozen foundation members, including Griffith’s youngest brother Simon, prepare for a camping trip. Outside, kangaroos graze and a pet pig waits to be patted. “Notice that pigs don’t go oink, oink—they go err, err,” says Griffith, never in a hurry to accept received wisdom.

Although there are occasional new members, the foundation’s numbers have not increased greatly in the past 10 years. Griffith is not concerned: “It’s enough people to set about presenting this information—a pioneer group who can evaluate the information despite the cynicism.”

When he sold his share of the furniture business, Griffith invested the money in the foundation. His brother Simon sold his youth hostel business and did likewise. (Other family members are not as impressed.) “We have our accountants to manage those funds and our own lawyers—we are building a self-sufficient structure,” says Griffith. Nobel Prize time is still a way off.

Published : THE BULLETIN, APRIL 21, 1998, Pages 28 & 29.