Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The New Biology

Part 8:4F Bonobos evidence the whole love-indoctrination, self-selection of integrativeness through mate selection process

While these recent fossil discoveries are providing exciting confirmation that our ape ancestors completed the development of the love-indoctrination process, of the living primate species, only bonobos have not only developed love-indoctrination but appear to have come close to completing the love-indoctrination process to become a fully integrated Specie Individual; they are certainly by far the most cooperative/harmonious/gentle/loving/integrated of the non-human primates. It follows then, that although there is no suggestion that bonobos or chimpanzees are a living human ancestor, comparisons have been made between bonobos and our ancestors. For instance, the physical anthropologist Adrienne Zihlman first proposed in 1978 ‘that, among living species, the pygmy chimpanzee (P. paniscus) offers us the best prototype of the prehominid [pre-human] ancestor’ (Adrienne L. Zihlman et al, ‘Pygmy chimpanzee as a possible prototype for the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas’, Nature, 1978, Vol.275, No.5682), using the then earliest known early human, Australopithecus, to compare the two species’ physical characteristics, including their bipedality, canine teeth and sexual size dimorphism. In 1996 Zihlman refined her assessment to include similarities with the, at the time, newly discovered Ardipithecus. In a further example, the primatologist Frans de Waal notes the extraordinary similarity between our ape ancestor and bonobos, saying, ‘The bonobo’s body proportions—its long legs and narrow shoulders—seem to perfectly fit the descriptions of Ardi, as do its relatively small canines’ (The Bonobo and the Atheist, 2013, p.61 of 289). Yes, bonobos are physically extremely similar to our fossil ancestors, but beyond the physical similarities, scientists are suggesting bonobo behaviour also corresponds with that of our ancestors. In addition to the view expressed above, that, like bonobos, Ardipithecus were not male dominated, Zihlman has suggested that ‘the Pan paniscus model offers another way to view the social life of early hominids, given their sociability, lack of male dominance and the female-centric features of their society’ (‘Reconstructions reconsidered: chimpanzee models and human evolution’, Great Ape Societies, eds. William C. McGrew et al, 1996, p.301 of 352).

Further comparison between bonobos and common chimpanzees clearly evidences what has been said about the love-indoctrination, sexual or mate selection process, for the bonobos make visible the entire process.

As mentioned, chimpanzees are found in equatorial Africa, north and east of the Congo River. The social model of the chimpanzee is patriarchal or male-dominated. Although there is a focus on nurturing of the young by chimpanzee mothers, the climatically unstable and geographically challenging environments in which chimpanzees live means their social bonds are periodically subjected to stress, such as from food scarcities during drier times. This has meant that the environment in which the females live is often disturbed by males aggressively competing for mating opportunities. This pressured existence also results in fierce inter-group confrontation. To allay food pressures, chimpanzees also regularly hunt colobus monkeys as a source of protein.

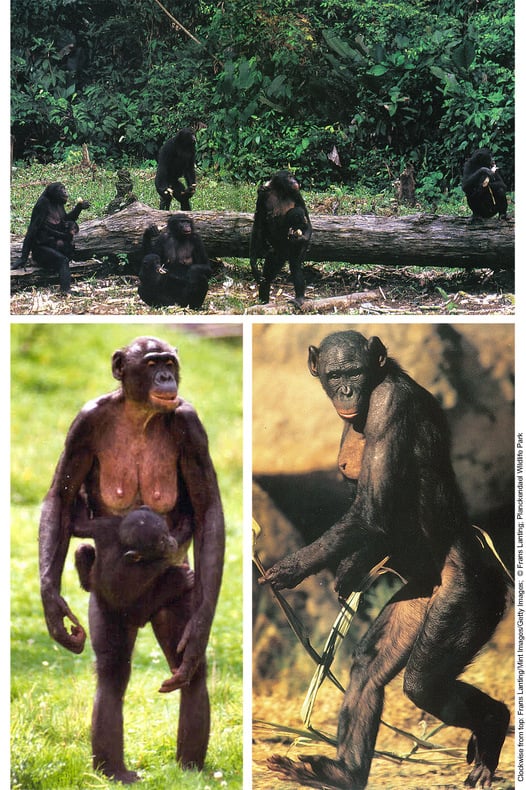

In contrast, bonobos live, as mentioned, in the ideal nursery conditions of the warm climate south of the Congo River, a stable environment that offers ample food and the sheltering safety of the jungle’s canopy for sleeping, eating and travelling. As a result, their social model is vastly different to that of chimpanzees. Firstly, as has been mentioned, the social dynamic of the bonobo society features a gender-role reversal to that of the chimpanzees in that bonobo females form alliances and dominate social groups, both of which are distinctly male activities in chimpanzee society. Bonobo societies are matriarchal, female-dominated, controlled and led, and the entire focus of the social group seems to be on the maternal or female role of nurturing infants. Bonobo females have, on average, one offspring every 5 to 6 years and provide better maternal care than chimpanzees. Bonobo infants are born small, develop more slowly than other ape species, and stay in a state of infancy and total dependence for a relatively long period of time—being weaned at about 5 years of age and remaining dependent on their mothers up until between 7 and 9 years of age. Chimpanzees are weaned at about 4 years of age and remain dependent for an average of 6 years. Not surprisingly, amongst the primates only bonobos have well-developed breasts similar to those of female humans—as the upcoming photos of bonobos show—presumably due to their emphasis on nursing.

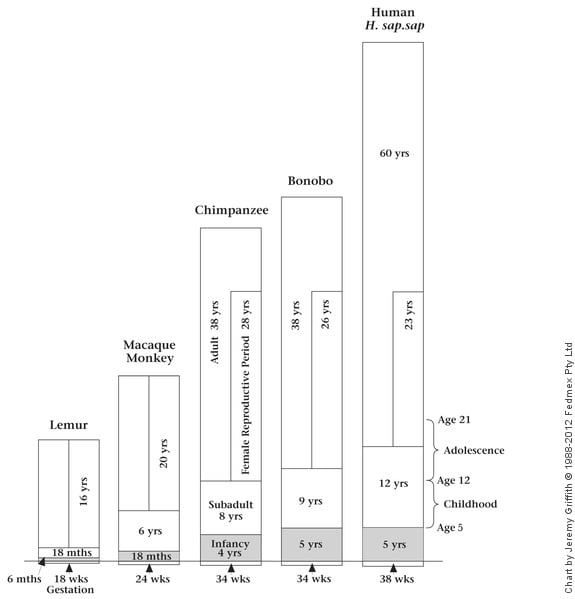

This chart shows the length of the infancy period for a number of primates. As indicated, lemurs have an infancy period of 6 months, whereas with macaque monkeys it is 18 months. In chimpanzees it is, as just mentioned, 3 to 4 years. Bonobos’ infancy period can last for up to 5 years, and in humans it does last 5 years. As mentioned, to develop love-indoctrination, selection has to occur for long infancies, for exceptionally maternal mothers and for females who have sufficiently strong characters to rein in male aggression. Also necessary are the exceptional nursery conditions of a peaceful and food-abundant environment, which the bonobos have had within the dense forests of the Congo basin in Africa (although the human race’s human-condition-afflicted, upset destructive behaviour is now threatening that haven). As explained, any breakdown in the nurturing process would result in a return to the pre-love-indoctrination, competitive state where male aggression from fighting for mating opportunities dominates.

It is possible that the selection for a longer infancy period had the side effect of lengthening all the stages of maturation—perhaps the stages are all linked genetically so that the extension of one stage results in the extension of all stages—because the age at which bonobos of both sexes reach sexual or reproductive maturity is 13 to 15 years, whereas in chimpanzees it is only 10 to 13 years for females and 12 to 15 years for males. This extension of all stages of maturation as a result of selecting for a longer infancy may explain how we humans acquired our comparatively long life span.

The primatologist Takayoshi Kano is one of the world’s leading experts on bonobos and since 1973 has led the long-running study of bonobos in their natural habitat, at a site in Wamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). In an interview conducted with Kano, his long-time collaborator Suehisa Kuroda contributed the following observation: ‘The long dependence of the son may be caused by the slow growth of the bonobo infant, which seems slower than in the chimpanzee. For example, even after one year of age, bonobo infants do not walk or climb much, and are very slow. The mothers keep them near. They start to play with others at about one and a half years, which is much later than in the chimpanzee. During this period, mothers are very attentive…Female juveniles gradually loosen their tie with the mother and travel further away from her than do her sons’ (Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, Frans de Waal & Frans Lanting, 1997, p.60 of 210). The bond between mother and son is of particular importance in bonobo society. The son will maintain his connection with his mother for life and will depend upon her for his social standing within the group. The son of the society’s dominant female, the strong matriarch that maintains social order, will rise in the ranks of the group, presumably to ensure the establishment and perpetuation of unaggressive, non-competitive, cooperative male characteristics, both learned and genetic, within the group. Again, historically, it is the male primates who have been particularly divisive in their aggressive competition to win mating opportunities and therefore the gender most needing of love-indoctrination—as this quote makes clear: ‘Patient observation over many years convinced [Takayoshi] Kano that male bonobos bonded with their mothers for life. That contrasts with chimpanzee males who rarely have close contact with their mothers after they grow up, instead joining other males in never-ending tussles for dominance’ (‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’ by Paul Raffaele, Last Tribes on Earth.com website).

The biologist and psychologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh is America’s leading ape-language researcher. In Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind (1994), she and co-author Roger Lewin offered this insight into bonobo society and its emphasis on nurturing: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among common chimps, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong. This high regard for infants gives bonobo females a status that is not shared by common chimpanzee females, who must bear the burden of child care all alone. Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group, with males invited in to the extent that they are cooperative and helpful. High-status males are those that are accepted by the females, and male aggression directed toward females is rare even though males are considerably stronger’ (p.108 of 299).

As mentioned, bonobos are much gentler than their chimpanzee cousins. They are relatively placid, peaceful and egalitarian, exhibiting a remarkable sensitivity to others—and not just sensitivity towards their own kind, as will be shown shortly when it is described how a bonobo cares for an injured bird. In fact, while physical violence is customary amongst chimpanzees it is rare among bonobos where, although the males are stronger, male aggression has been tamed and, unlike other great apes, there is actually little difference in size between the male and female of the species. Bonobos also have reduced canine teeth, another indication they are less aggressive. As mentioned, even sex has been employed by bonobos as an appeasement device for subsiding conflict and tension. The practice of infanticide, while not uncommon amongst chimpanzees, also appears to be non-existent within bonobo societies where even orphan bonobos are cared for by the group. In chimpanzee society orphans are occasionally adopted by a female but are not especially cared for by the group. Social groups of bonobos also have much greater stability than social groups of chimpanzees, with bonobos periodically coming together in large, harmonious, stable groups of up to 120 individuals. For instance, the anthropologist Barbara Fruth, who had spent many years studying bonobos in their natural habitat, observed that ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, 2003, Last Tribes on Earth.com).

Unlike chimpanzees, bonobos also regularly share their food and while the former restrict their plant-food intake to mainly fruit, bonobos eat leaves and plant pith as well as fruit, a diet more like that of gorillas. While bonobos have been known to capture and eat small game, they are not known to routinely hunt down and eat large animals such as monkeys, like chimpanzees do.

The following extract from the 1995 National Geographic documentary The New Chimpanzees provides a good example of the important role a strong matriarchy plays in the prevention of divisive selfish and aggressive behaviour. To quote from the narration: ‘An impressively stern [bonobo] female enters and snaps a young sapling. Once she picks herself up she does something entirely surprising for a female chimp, she displays [the female is shown assertively dragging the sapling through the group], and the males give her sway [a male is shown cowering out of her way]. For this is the confident stride of the group’s leader, its alpha female, whom [Takayoshi] Kano has named Harloo.’ As mentioned in Part 5:1, those who have studied primates will typically tell you of an extraordinarily self-assured, secure-in-self and strong-willed female in their study group. All primates are trying to develop the nurturing of integrativeness but only our ancestors and the bonobos have had the right conditions to achieve it. In that Part, when illustrating the strength of character that had to be developed to curtail male aggression and the centred security of self needed to be a good mother, it was mentioned how the American primatologist Dian Fossey, whose work will be further referred to shortly, studied gorillas in the mountain forests of Rwanda in Africa for some 18 years. In her 1983 book Gorillas in the Mist, Fossey wrote about a remarkably assured female gorilla named ‘Old Goat’ who was such ‘an exemplary parent’ (p.174 of 282) that her son ‘Tiger’ ‘was a contented and well-adjusted individual whose zest for living was almost contagious’ (p.186). During a trip to Kenya in 1992, my partner Annie Williams and I were invited to visit anthropologist Shirley Strum’s ‘Pumphouse Gang’ study troop of baboons, which had been made famous through numerous articles in National Geographic magazine. During our visit I noticed that Strum kept on her desk the skull of a baboon named Peggy. Displaying a skull is, as I said earlier, a bit macabre but Strum said she did so in memory of Peggy who was an extraordinarily confident, strong-willed, authoritative, charismatic individual who successfully led the Pumphouse Gang for many years. As Strum has written: ‘She [Peggy] was the highest-ranking female in the troop, and her presence often turned the tide in favor of the animal she sponsored. While every adult male outranked her by sheer size and physical strength, she exerted considerable social pressure on each member of the troop. Her family also outranked all the others…another reason for the contentment in this particular family was Peggy’s personality. She was a strong, calm, social animal, self-assured yet not pushy, forceful yet not tyrannical’ (Almost Human: a journey into the world of baboons, 1987, pp.38-39 of 294).

Physically, bonobos have more slender upper bodies than chimpanzees, are more arboreal and often walk upright; in fact, they are by far the most upright of the great apes. It has long been claimed that it was the move to savannah and the associated need to see over tall grass that led to bipedalism, yet the bonobos live in the jungle, so some other influence must be at work selecting for upright walking/bipedalism and, as described, the evidence indicates that influence was the need to develop nurturing.

Indeed, the integrative, neotenising effects of nurturing and its role in the emergence of bipedalism, together with the effect of exceptionally strong-willed females helping to rein in any aggression resulting from males’ competition for mating opportunities, is apparent in the pre-four-million-year-old fossil evidence that was referred to earlier: ‘The 4.4 million-year-old skeleton of a likely human ancestor known as Ardipithecus ramidus’, discovered in Ethiopia in 1994, shows ‘males lacked the daggerlike fangs of gorillas and chimps’, while other features showed they ‘walked upright on two legs’ (‘A Long-Lost Relative’, TIME mag. 12 Oct. 2009). Since reduced canines are a feature of the more juvenile state we can attribute such reduction in adults to the neotenising selection of less aggressive mates. I might mention that this TIME article erroneously suggested that ‘bipedality arose’ for ‘carrying food’. Again, as was pointed out earlier, and as will be elaborated upon in Part 8:5, the all-important role of nurturing in human origins that led to bipedalism has been too confronting to admit for us upset humans who have understandably been incapable of adequately nurturing our children while the battle of the human condition raged. It is only now that the human condition is explained that it becomes safe to confront and admit the significance of nurturing in both the maturation of our species and in the maturation of our individual lives.

These photographs show the aforementioned large breasts so characteristic of female bonobos as well as the species’ exceptionally upright stance—they are, as stated above, the most bipedal of all the non-human living primates. The longer our ape ancestors had to hold infants, the greater the need became to stand upright, so if we want to assess how much ‘love-indoctrination’ a primate species has been able to develop we only have to look at how bipedal they have become.

In addition to their remarkably neotenous physical appearance, there is also a marked variance in features between individual bonobos, suggesting the species is undergoing rapid change. This in turn suggests that the bonobo species has hit upon some opportunity that facilitates a rapid development, which evidence indicates is the ability to develop integration through love-indoctrination and mate selection.

We can see then that of all the non-human primates bonobos are by far the most integrated—that is, cooperative and thus peaceful. As has already been mentioned, bonobos are also exceptionally intelligent, almost certainly the most intelligent species after humans. As explained, nurturing liberated consciousness and with it insightful intelligence, so the fact that the bonobos have been able to develop such a high degree of nurturing and are also so intelligent evidences that explanation for the origin of consciousness.

This quote, part of which was included earlier in Part 8:4C, reveals how much more intelligent bonobos are than chimpanzees—as well as their nurtured happy disposition and greater psychological ‘room’: ‘Everything seems to indicate that [Prince] Chim [a bonobo] was extremely intelligent. His surprising alertness and interest in things about him bore fruit in action, for he was constantly imitating the acts of his human companions and testing all objects. He rapidly profited by his experiences…Never have I seen man or beast take greater satisfaction in showing off than did little Chim. The contrast in intellectual qualities between him and his female companion [a chimpanzee] may briefly, if not entirely adequately, be described by the term “opposites” [p.248 of 278]…Prince Chim seems to have been an intellectual genius. His remarkable alertness and quickness to learn were associated with a cheerful and happy disposition which made him the favorite of all [p.255]…Chim also was even-tempered and good-natured, always ready for a romp; he seldom resented by word or deed unintentional rough handling or mishap. Never was he known to exhibit jealousy…[By contrast] Panzee [the chimpanzee] could not be trusted in critical situations. Her resentment and anger were readily aroused and she was quick to give them expression with hands and teeth [p.246]’ (Almost Human, Robert M. Yerkes, 1925). It will be described shortly in Part 8:4H how this conscious intelligence that we can see rapidly emerging in the bonobos led to one variety of ape, or perhaps some varieties of apes, to develop into what we recognise in the fossil record as the australopithecines, and from the australopithecines into the upset, human-condition-afflicted genus Homo—us modern humans.

The following section of dialogue about bonobos, from a 1996 Discovery Channel documentary titled The Ultimate Guide: Great Apes, confirms some of the main points that have been made about the species thus far. The segment commences with this observation by the primatologist Jo Myers Thompson: ‘A female chimpanzee’s life is rugged. They have hardships just in daily activities. They are probably lower on the hierarchy, the social status, than males throughout the society and for instance males beat them up, chase them, bully them around and that doesn’t happen in bonobo society. The female bonobos are not bullied and chased. Although there can be some male aggression it’s very minor. Female bonobos are never raped as far as we know; they have first choice at feeding sites. Their life is much more peaceful.’ The program’s narrator then states: ‘The physical difference between chimps and bonobos are quite telling. Bonobos have shorter, smaller faces and a more slender physique retaining many of the features seen in juvenile chimps. They’re rather like chimps frozen inside adolescent bodies. Even their voices are high-pitched and child-like. The male aggression that is so common in chimps is much reduced in bonobos and even relations between neighbouring groups are often peaceful.’ Thompson concludes: ‘Why do they [bonobos] need to be aggressive? They don’t have to fight for food, they don’t have to fight for sex, they don’t have to fight for inter-relationships, they don’t have to fight for space. Why would they be aggressive?’ As has been pointed out, ideal nursery conditions alone aren’t enough to develop love-indoctrination—there also had to be the ability to hold a dependent infant and thus be able to select for the longer infancy period necessary for the love-indoctrination to take place. If all that was required to produce an integrated, fully cooperative species of large animal was the presence of ideal nursery conditions then it would have been developed many times over because such ideal nursery conditions would not have been that uncommon over the millions of years of biological evolution.

The following quotes offer further insight into how extraordinarily integratively orientated bonobos are and just how wonderful our species’ time in the innocent, cooperatively-behaved, loving, ‘Garden of Eden’, fully integrated, ‘heavenly’ ‘Golden Age’ must have been. In fact, I doubt you will find a better clue to our glorious past, and now future, than what you are about to read.

Firstly, this extract from an article titled ‘The Bonobo: “Newest” apes are teaching us about ourselves’ demonstrates how extraordinarily sensitive, cooperative, loving and intelligent bonobos are, as well as how few exist in captivity: ‘Barbara Bell…a keeper/trainer for the Milwaukee County Zoo…works daily with the largest group of bonobos (5 males and 4 females, ranging in age from 3 to 48 years) in North America, making it the second largest collection in the world (the largest can be found at the Dierenpark Planckendael, in Mechelen, Belgium). There are only 120 captive worldwide. “It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day,” she [Bell] says. “They’re extremely intelligent.”…“They understand a couple of hundred words,” she says. “They listen very attentively. And they’ll often eavesdrop. If I’m discussing with the staff which bonobos (to) separate into smaller groups, if they like the plan, they’ll line up in the order they just heard discussed. If they don’t like the plan, they’ll just line up the way they want.” “They also love to tease me a lot,” she says. “Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh. But what really blows me away is their ability to understand a situation entirely.” For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. “They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go,” says Bell. “That’s pretty amazing. Adults demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other.” The bonobo’s apparent ability to empathize, in contrast with the more hostile and aggressive bearing of the related chimpanzee, has some social scientists re-thinking our behavioral heritage’ (Anthony DeBartolo, Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998).

It should be explained that the reason the term ‘newest’ ape is used in the article above, and in the title of the documentary referred to earlier, is because bonobos were only identified as a species separate from chimpanzees in 1928. I might also mention that while they are an endangered species, rare both in the wild and in captivity, many zoos have been reluctant to exhibit bonobos because their overt sexual behaviour has been deemed too embarrassing for the public—surely a problem that can be managed with the right educational information and a sensitive presentation. Such censorship is also a very great shame because it denies the public the chance to view the species that more than any other throws light on the true, loving, soulful nature of our own human origins. Next to humans, bonobos are the most astonishing animals on Earth because, for a large animal, they are so extraordinarily loving and thus integrated. In fact, they are presently more loving than we are—which is obviously a contributing reason for the reluctance to put them on display: they have just been far too confronting for us upset humans!

In 1997 the primatologist Frans de Waal and photographer Frans Lanting released a book titled Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape that features another example from Barbara Bell of the truly extraordinary empathy and kindness that exists between bonobos. Fittingly, the extract comes from a chapter titled ‘Sensitivity’: ‘Kidogo, a twenty-one-year-old bonobo at the Milwaukee County Zoo suffers from a serious heart condition. He is feeble, lacking the normal stamina and self-confidence of a grown male. When first moved to Milwaukee Zoo, the keepers’ shifting commands in the unfamiliar building thoroughly confused him. He failed to understand where to go when people urged him to move from one place to another. Other apes in the group would step in, however, approach Kidogo, take him by the hand, and lead him in the right direction. Barbara Bell, a caretaker and animal trainer, observed many instances of such spontaneous assistance and learned to call upon other bonobos to move Kidogo. If lost, Kidogo would utter distress calls, whereupon others would calm him down or act as his guides’ (p.157 of 210).

The same book contains this description of the bonobo’s apparent sensitivity towards other creatures: ‘Betty Walsh, a seasoned animal caretaker, observed the following incident involving a seven-year-old female bonobo named Kuni at Twycross Zoo in England. One day, Kuni captured a starling. Out of fear that she might molest the stunned bird, which appeared undamaged, the keeper urged the ape to let it go. Perhaps because of this encouragement, Kuni took the bird outside and gently set it onto its feet, the right way up, where it stayed, looking petrified. When it didn’t move, Kuni threw it a little way, but it just fluttered. Not satisfied, Kuni picked up the starling with one hand and climbed to the highest point of the highest tree, where she wrapped her legs around the trunk, so that she had both hands free to hold the bird. She then carefully unfolded its wings and spread them wide open, one wing in each hand, before throwing the bird as hard as she could towards the barrier of the enclosure. Unfortunately, it fell short and landed onto the bank of the moat, where Kuni guarded it for a long time against a curious juvenile. By the end of the day, the bird was gone without a trace or feather. It is assumed that, recovered from its shock, it had flown away’ (p.156).

In the aforementioned book, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, Sue Savage-Rumbaugh recounts the extreme elation and affection shown by her famous bonobo research subject, the young adult male Kanzi, when reunited with his mother Matata after a number of months apart: ‘I sat down with him [Kanzi] and told him there was a surprise in the colony room. He began to vocalize in the way he does when expecting a favored food—“eeeh….eeeh….eeeh.” I said, No food surprise. Matata surprise; Matata in colony room. He looked stunned, stared at me intently, and then ran to the colony room door, gesturing urgently for me to open it. When mother and son saw each other, they emitted earsplitting shrieks of excitement and joy and rushed to the wire that separated them. They both pushed their hands through the wire, to touch the other as best they could. Witnessing this display of emotion, I hadn’t the heart to keep them apart any longer, and opened the connecting door. Kanzi leapt into Matata’s arms, and they screamed and hugged for fully five minutes, and then stepped back to gaze at each other in happiness. They then played like children, laughing all the time as only bonobos can. The laughter of a bonobo sounds like the laughter of someone who has laughed so hard that he has run out of air but can’t stop laughing anyway. Eventually, exhausted, Kanzi and Matata quieted down and began tenderly grooming each other’ (pp.143-144 of 299).

Further wonderful descriptions of the extraordinarily integrative behaviour of bonobos can be found in the Australian primatologist Vanessa Woods’ 2010 book, Bonobo Handshake.

To conclude this description of the incredible world of bonobos I should again emphasise their ability to nurture their infants, especially since this ability to nurture is the key to the whole love-indoctrination process. While some remarkable photographs of bonobo mothers with their infants were included earlier in Part 8:4B, the most revealing evidence I have seen of the ability of bonobos to nurture their infants and the wondrous effects such nurturing has on their offspring appears in the 2011 French documentary Bonobos, which was directed by Alain Tixier. A short segment from the documentary showing the tenderness of the bonobo mothers and the absolute joy and zest for life of their infants can be seen at www.wtmsources.com/107. Copies of the documentary are difficult to obtain, however, we managed to order one through <www.amazon.fr>. If you can’t understand the French commentary, it is a story about a young bonobo called Beny who is sold as a pet after his mother is killed by poachers and then rescued by Claudine André who takes him to her wonderful sanctuary called Lola Ya Bonobo before eventually releasing him back into the Congo forest. While the commentary is superficial, there are these two very revealing comments in the short film about the making of the documentary. Alain Tixier says to camera, ‘The choice to do a film about bonobos was because they’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man. They’re the only animals capable of creating the same “gaze” as a human. When you look at a bonobo you’re taken aback because you can see behind the eyes it’s not just curiosity, it’s understanding. We see human beings in the eyes of the bonobo.’ And the film’s animal advisor, Patrick Bleuzen, says to camera, ‘Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience.’