Beyond The Human Condition

Page 101 of

Print Edition 8. How We Acquired Consciousness

Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum

William Blake’s frontispiece to Songs of Experience (1794) is an extraordinarily

prophetic image of nurturing or love-indoctrination liberating consciousness.

AN accidental by-product of love-indoctrination was the liberation of conscious thought. Most species have a block in their minds stopping conscious thought. Before explaining how this block developed and how love-indoctrination was able to overcome it, I should describe the conscious thinking process and explain why we have avoided describing it clearly in the past.

As already noted, the nerve-based learning system, able to remember past events, can compare them with current events and identify regularly occurring experiences. This knowledge of, or insight into, what has commonly occurred in the past enables the mind to predict what is likely to occur in the future and to adjust behaviour accordingly. The nerve-based learning system can associate information, reason how experiences are related, learn to understand and become conscious of the relationship of events that occur through time.

In the brain, nerve information recordings of experiences (memories) are examined for their relationship with each other. To understand how the brain makes the comparisons, Page 102 of

Print Edition we can think of the brain as a vast network of nerve pathways onto which incoming experiences are recorded or inscribed, each on a particular path within the network. Where different experiences share the same information, their pathways overlap. For example, long before we understood what the force of gravity was, we had learnt that if we let go of an object, it would usually drop to the ground. The value of recording information as a pathway in a network is that it allows related aspects of experience to be physically related. In fact the area in our brain where information is related is called the ‘association cortex’. Where parts of an experience are the same they share the same pathway and where they differ their pathways differ or diverge. All the nerve cells in the brain are interconnected, so with sufficient input of experiences onto a nerve network of sufficient size, similarities or consistencies in experience show up as well-used pathways that have become highways. (In the vast convolutions of our cortex there are about 8 billion nerve cells with 10 times that number of interconnecting dendrites which, if laid end to end, would stretch at least from Earth to the Moon and back.)

An ‘idea’ describes the moment information is associated in the brain. Incoming information could reinforce a highway, slightly modify it or add an association (an idea) between two highways, dramatically simplifying that particular network of developing consistencies to create a new and simpler interpretation of that information. For example, the most important relationship between different types of fruit is their edibility. Elsewhere the brain has recognised that the main relationship connecting experiences with living things is that they appear to try to stay alive. Suddenly it ‘sees’ or deduces (‘tumbles’ to the idea or association or abstraction, as we say) a possible connection between eating and staying alive which, with further experience and thought, becomes reinforced or ‘seems’ correct. ‘Eating’ is now channelled onto the ‘staying alive’ highway. Subsequent thought would try to deduce the significance of ‘staying alive’ and, beyondPage 103 of

Print Edition that, compare the importance of selfishness and selflessness. Ultimately the brain would arrive at the truth of integrative meaning.

Forgetting also plays a part in understanding (the relationship between experiences). Because duration of nerve memory is related to use, our strongest memories will be of those highways, those experiences of greatest relationship. Our experiences not only become related or associated in the brain, they also become concentrated because the brain gradually forgets or discards inconsistencies or irregularities between experiences. Forgetting serves to cleanse the network of less consistently occurring information, preventing it becoming cluttered with meaningless (non-insightful) information.

Our language development took the same path as the development of understanding. Commonly occurring arrangements of matter and commonly occurring events were identified (became clear or stood out). Eventually all the main objects and events became identified. In the case of language they were named. For example those regularly occurring arrangements of matter with wings we named ‘birds’ and what they often did we termed ‘flying’.

Once insights into the nature of change are put into effect, the self-modified behaviour starts to provide feedback, refining the insights further. Predictions are compared with outcomes leading all the way to the deduction of the meaning to all experience, which is to develop integration of matter.

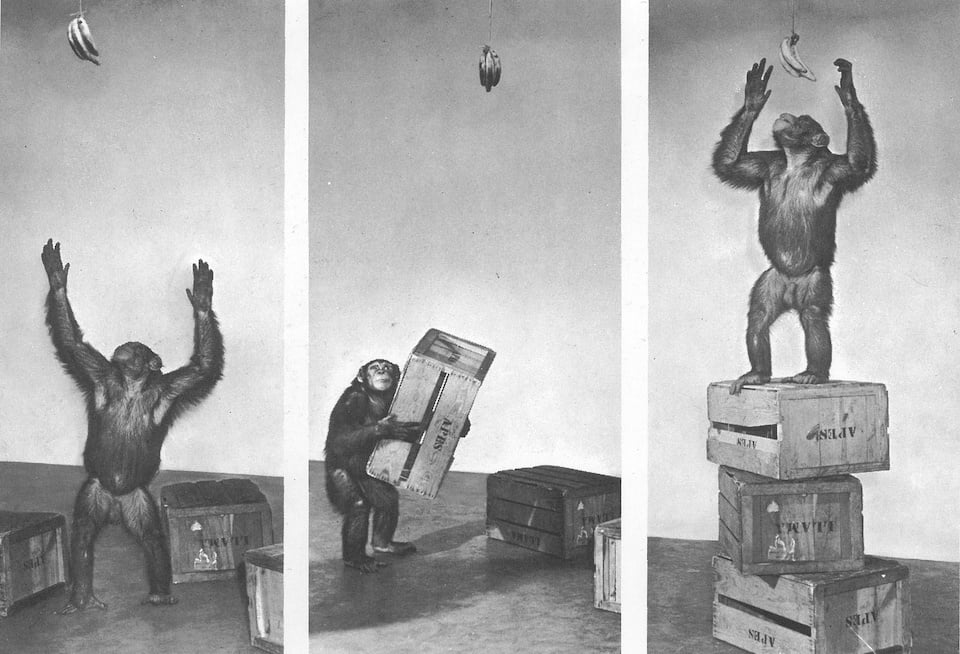

Consciousness is the ability to understand the relationship of events sufficiently well to be able to effectively/successfully manage and manipulate those events. For example chimpanzees demonstrate consciousness when they stack boxes and climb them to reach bananas tied to the roof of their cage. Consciousness is when the mind Page 104 of

Print Edition becomes effective, able to understand how experiences are related. It’s the point at which the confusion of incoming information clears, starts to fit together or make sense and the mind becomes master of change. (Note, it is one thing to be able to stack boxes to reach bananas — to manage immediate events — but quite another to manage events over the long term, to be secure managers of the world. Infancy is when we discover conscious free will, the power to manage events. Childhood is when we revel in free will and adolescence is when we encounter the sobering responsibility of free will.)

Photographs by Lilo Hess

Consciousness has been a difficult subject for humans to investigate, not because of practical difficulties in understanding how our brain works as we’re told but because we did not want to know how it worked. We have had to evade admitting too clearly how the brain worked because admitting information could be associated and simplified — admitting to insight — was only a short step away from realisingPage 105 of

Print Edition the ultimate insight, integrative meaning, immediately confronting ourselves with our inconsistency with that meaning. Better to evade the existence of purpose in the first place by avoiding the possibility that information could be associated. For the same reason we evaded the term ‘genetic refinement’ preferring instead the vaguer term genetics. We had to evade the possibility of the refinement of information in all its forms. Admitting that information could be simplified or refined was admitting to an ultimate refinement or law, again confronting us with our inconsistency with that law.

In fact we have avoided not only the idea of meaningfulness but deep, meaningful thinking, which would lead to confrontation with integrative meaning, against which we had no defence. By making deeper insights hard to reach we saved ourselves from exposure but in the process we buried the truth.

Illustrative of our evasion of the nature of consciousness we used the words ‘conscious’, ‘intelligent’, ‘understanding’, ‘reason’ and ‘insight’ regularly without ever saying what we are conscious of, being intelligent about, understanding, reasoning or having an insight into, which is how events or experiences are related. The conventional obscure, evasive definition of intelligence is ‘the ability to think abstractly’. It was a slip of our evasive guard to name the area of the brain that associates and simplifies information as the ‘association cortex’. Of course when we weren’t ‘on our guard’ against exposure few of us would deny that information can be associated, simplified and meaning found. In fact, most of us would say we do it every day of our lives. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t have a word for ‘insight’. But that is the amazing thing about our evasion. We can accept an idea up to a point and then without ‘batting an eyelid’ go on to pretend it doesn’t exist once it starts to lead to a dangerous conclusion.

Our evasion is often obviously false and yet because we have to, we believe it. Look at our evasion of integrative meaning. We are surrounded by integrativeness and yet wePage 106 of

Print Edition deny it. Every object we look at is a hierarchy of ordered matter — an example of the development of order of matter. Our body is composed of parts that are composed of smaller parts, etc. etc. In another example, science doesn’t even have a definition for ‘love’ which is one of our most used words/concepts. It takes time to become used to the extent of humanity’s evasions, our blindness.

In summation, ‘insight’ was the term given to the nerve highways, the correlation our brain made of the consistencies or regularities it found between events through time. Once we could deduce these insights, these laws governing events in time past, we were in a position to predict or anticipate the likely turn of events. We could learn to understand what happened through time. Our intellect can deduce or distil the purpose to existence or the design inherent in change in information; it can learn the predictable regularities or common features in experience.

Now that we can acknowledge the process of associating experiences that consciousness depends on, the significance of the roles of the left and right hemispheres of the brain become clear.

The right side of the brain specialises in general pattern recognition while the left specialises in specific sequence recognition. The right is lateral or creative or imaginative while the left is vertical or logical or sequential. The right stands off to ‘spot’ any overall emerging relationship while the left goes in and takes the heart of the matter to its conclusion. We need both because logic alone could lead the intellect into a dead-end. For example, we can imagine that at one point the most obvious association the brain attributed to fruit would have been that it was brightly coloured. However, with more experience the greatest relevance would have been attributed to their edibility. Similar processes occurred in genetic thinking. Dinosaurs seemed to be a successful idea at one stage but ultimately proved otherwise and ‘nature’ had to back off and take another approachPage 107 of

Print Edition towards integration, namely mammals. When one thought process leads to a dead-end the mind has to back off and find another way in. It goes from the general to the particular and back to the general, until our thinking finally breaks through to the correct association/understanding.

The first form of thinking to wither during alienation was the imagination, because wandering around freely in the mind soon brought us into contact with integrative meaning and its implied criticism. On the other hand if we got onto a logical train of thought that didn’t immediately attract criticism there was a much better chance it would stay safely non-critical. Children have wonderful imaginations that they lose before they become adults because they haven’t learnt to avoid free/open/adventurous/lateral thinking. Edward de Bono, who trains people to use their imagination again and who has popularised it as ‘lateral thinking’, once said often the pupil who is not considered bright will be the best thinker. (The Australian, March 3, 1975.) Figs. 2 and 3 (pages 130 — 131) show that under the human condition alienation increased with intelligence. (Note: these charts are only intended to approximate the developments they describe.) The truth is that in order to think imaginatively we had to remove the need for evasion/alienation. We had to end the human condition.

______________________

There must be a reason why other animals haven’t developed full mental consciousness; what is it?

One of the integrative limitations of genetic refinement is that it can’t reinforce selfless behaviour. In fact, it actively resists it.

Where I live, I can observe the behaviour of a group of kangaroos. Whenever a female comes into season, all the males pursue her relentlessly, attempting to mate with her. So exhausted do the female and the pursuing males become, eventually they are all almost falling with fatigue, yet still the chase goes on. It is easy to see how this behaviour developed.Page 108 of

Print Edition If a male relaxed his efforts he would lose his chances of producing offspring. Self-interest is fostered by natural selection (genetic refinement). Genetic selfishness is an extremely strong force in animals. It is clear that there would be no chance of a variety of kangaroo developing that considered others above itself. Unconditional selflessness disadvantages the individual that practises it and advantages the recipients of the selfless treatment (such is the meaning of selflessness). At this stage in development genetic refinement automatically acts against any inclination towards selfless behaviour.

In terms of the development of thought this means that genetic refinement was, in effect, totally against a brain thinking selflessness is meaningful. Genetic refinement resisted altruistic thinking in animals. In fact, it developed blocks in their minds against the emergence of such thinking.

In ‘visual cliff’ experiments newly born kittens crawl to the edge of a table but won’t venture over the edge. Presumably, they have an instinctive orientation against going over cliffs. Any kitten that crawled over a cliff fell to its death, leaving only those that happened to have an instinctive block against such self-destructive practices. Natural selection or genetic refinement develops blocks in the mind against behaviour that doesn’t tend to lead to the reproduction of the genes of the individuals who practise that behaviour.

Just as surely as kittens were eventually selected for their instinctive block against self-destruction, so were animals selected with an instinctive block against selfless thinking. The effect of this block was to stop the developing intellect from thinking truthfully and thus effectively.

As was explained in the chapter Science and Religion selflessness or love is the theme of existence, the essence of integration, the meaning of life. (Christ made the point when he said: Greater love has no-one than this, that one lay down his life for his friends [The Bible, John 15:13]). If you aren’t able to appreciate the significance of selflessness/integrativeness you can’t begin to make sense of experience. It is this blockPage 109 of

Print Edition against truthful, selflessness-recognising-thinking in most animals’ minds that prevents them from becoming conscious (of the true relationship/meaning of experience).

To elaborate, any animal able to associate information to the degree necessary to realise the importance of being selfless towards others would have been at a distinct disadvantage (in terms of its chances of reproducing its genes). Those that don’t perceive the importance of selflessness are genetically advantaged. Eventually a mental block would have been ‘naturally selected’ to stop the emergence of mental cleverness (at associating information). At this point in development, genetic refinement favoured individuals that were not able to recognise the significance of selflessness. The effect was to keep animals stupid, unconscious of the true meaning of life.

Having evaded integrative meaning and the importance of selflessness, it’s not easy for us to appreciate that conscious thought depends on the ability to acknowledge the significance of selflessness. The fact is, our own mental block or alienation is the perfect illustration of, and parallel for, this block in animals’ minds. Unable to think truthfully/straight we have been unable to think effectively. Alienation has rendered us almost stupid, incapable of deep, penetrating, meaningful thought. The human mind has been alienated from the truth twice in its history: once when we were like other animals, instinctively blocked from recognising the truth of selflessness, and again in our adolescence (which we are just leaving) when we became insecure about our divisive nature and evaded the significance of selflessness and the truth of integrative meaning.

Quite by accident, love-indoctrination breached the block against thinking truthfully by superimposing a new, truthful, selflessness-recognising mind over the older, blocked one. Since our ape ancestors could develop love-indoctrination they were also able to develop truly selfless integrative thinking. They were free to think properly, soundly, effectively andPage 110 of

Print Edition truthfully and so acquired consciousness (the essential characteristic of mental infancy). Chimpanzees are in mental infancy and demonstrate rudimentary consciousness, making sufficient sense of experience to recognise that they are at the centre of the changing array of events they experience. They are beginning to relate information or reason effectively. Experiments have shown they have an awareness of the concept of ‘I’ or self. Also, as mentioned earlier, they are capable of reasoning how events are related sufficiently well to know that by stacking boxes and climbing them they can reach a banana tied to the roof of their cage.

How did love-indoctrination overcome the instinctive blocks? What actually took place? At the outset the brain was small, with only a small amount of cortex (where information is associated). In this relatively small brain were instinctive blocks orientating the mind away from deep meaningful/truthful/selflessness-recognising perceptions. At this stage these small inhibited brains were then love-indoctrinated, so although there wasn’t much unfilled cortex available, what was there was being inscribed with a truthful, effective network of information-associating pathways. The mind was being taught the truth and given the opportunity to think clearly, over and in spite of the existing instinctive ‘lies’ or blocks. At first, with the brain so small, this truthful ‘wiring’ would not have been very significant but it could be developed.

So the mind was trained or ‘brain-washed’ with the ability to think in spite of the blocks against it. It had been stimulated by the truth at last. Of course it must be remembered that the emphasis in this early stage of the development of love-indoctrination was on training in love, not liberation of the ability to think, which was incidental to the need for integration.

The development of thought, which had been liberated accidentally, was only gradual. The association cortex didn’t develop strongly until thinking became a necessity inPage 111 of

Print Edition humanity’s adolescence (when we had to find understanding to defend ourselves against ignorance). The large association cortex is a characteristic of Adolescentman Homo.

Traditionally the long primate infancy is said to have developed so infants could be taught survival skills, but the evidence shows that learning wasn’t strongly promoted until adolescence — after the extended infancy. Now that we don’t have to be evasive we can admit the truth, that the long infancy was solely for the development of integration.

The ‘need to learn survival skills’ explanation implies that survival was a problem, but there had to be ideal nursery conditions for love-indoctrination to develop, which means an environment free of survival difficulties. For example, love-indoctrination and consciousness are more developed in the pygmy chimpanzee than in the common chimpanzee because of the extra comfort and security of the pygmy chimpanzee’s environment.

. . . we may say that the pygmy chimpanzees historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food. Pygmy chimpanzees appear conservative in their food habits and unlike common chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure and elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior. In contrast, common chimpanzees have gone further in developing their resource-exploiting techniques and strategy, and have the ability to survive in more varied environments. These differences suggest that the environments occupied by the two species since their separation by the Zaire River has differed for some time. The vegetation to the south of the Zaire River, where Pan paniscus [pygmy chimpanzee] is found, has been less influenced by changes in climate and geography than the range of the common chimpanzee to the north. Prior to the Bantu (Mongo) agriculturists’ invasion into the central Zaire basin, the pygmy chimpanzees may have led a carefree life in a comparatively stable environment.

The Pygmy Chimpanzee, Edited by Randall L. Susman, 1984, from Chapter 10: Feeding Ecology of the Pygmy Chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) of Wamba, by Dr Takayoshi Kano and Dr Mbangi Mulavwa.

Page 112 of

Print Edition The above would seem to indicate that having to live in more variable and less food-rich environments, common chimpanzees have the greater need for intelligence, but that can only be liberated by love-indoctrination and in fact the pygmy chimpanzee is the more conscious or intelligent of the two species.

Everything seems to indicate that [Prince] Chim [a pygmy chimpanzee] was extremely intelligent. His surprising alertness and interest in things about him bore fruit in action, for he was constantly imitating the acts of his human companions and testing all objects. He rapidly profited by his experiences. . . . Never have I seen man or beast take greater satisfaction in showing off than did little Chim. The contrast in intellectual qualities between him and his female companion [a common chimpanzee] may briefly, if not entirely adequately, be described by the term ‘opposites’.

Prince Chim seems to have been an intellectual genius. His remarkable alertness and quickness to learn were associated with a cheerful and happy disposition which made him the favorite of all . . .

Chim also was even-tempered and good-natured, always ready for a romp; he seldom resented by word or deed unintentional rough handling or mishap. Never was he known to exhibit jealousy. . . [By contrast] Panzee [the common chimpanzee] could not be trusted in critical situations. Her resentment and anger were readily aroused and she was quick to give them expression with hands and teeth.

Robert M. Yerkes (who has been described as the dean of American primatologists), Almost Human, 1925, from pages 248, 255 and 246 respectively.

Page 113 of

Print Edition

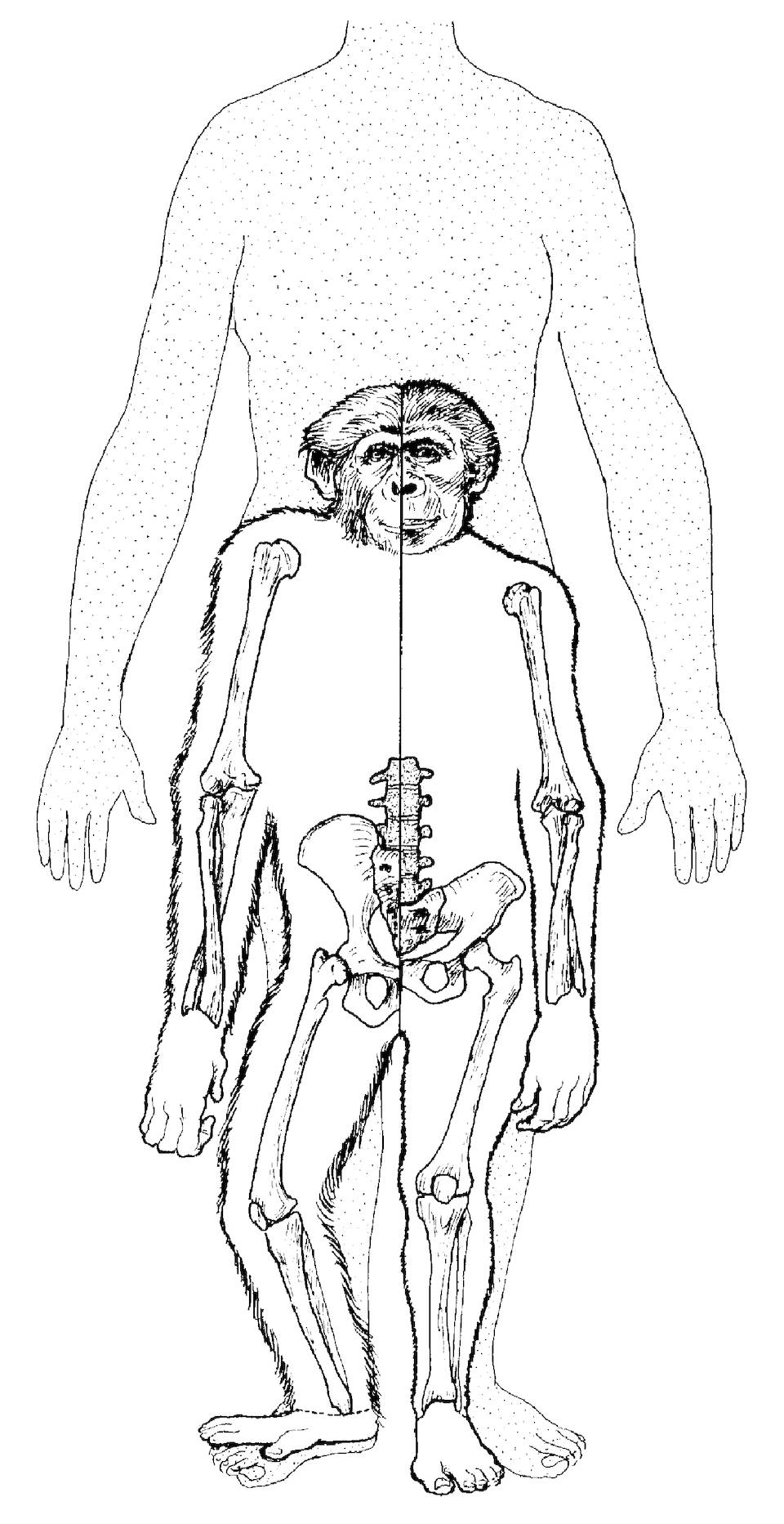

Fossil remains of Early Prime of Innocence Childman, Australopithecus afarensis (right) match up remarkably well with the skeleton of a pygmy chimpanzee. The main differences are that A. afarensis had a bipedal rather than quadrupedal pelvis, shorter limbs, larger molars and pre-molars and slightly smaller canine teeth. Pygmy chimpanzees have smaller canine teeth and molars than other apes. A modern human outlined at rear facilitates size comparison.

Drawing by Adrienne L. Zihlman (Professor of Anthropology UC

Santa Cruz) from her book. The Human Evolution Coloring Book, 1982.

Pygmy chimpanzees are exceptionally integrated and are on the threshold of childhood.

We saw above that Chim seldom resented by word or deed unintentional rough handling or mishap. The following Page 114 of

Print Edition account of Matata, a female pygmy chimpanzee captured in the ‘wild’, confirms this tolerance, but more importantly, also illustrates the exceptional mothering that love-indoctrination depends on.

Kanzi was stolen from his mother (without contest) 30 min after birth by Matata and has been reared by Matata as her son since that time . . .

Matata had conceived and borne one infant of her own, Akili . . . Matata cared very adroitly for both infants . . . When . . . 9 months of age, Akili was sent to the San Diego Zoo. Kanzi and Matata were assigned to the language project and remained together . . .

Matata and Kanzi are housed in a large six-room indoor-outdoor enclosure [at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center in Georgia, USA]. Even though Matata was wild-born, both she and Kanzi continually seek out and appear to enjoy and depend upon human companionship. Consequently, human teachers and caretakers are with them throughout the day. Mild distress is evidenced by Matata, even though she is an adult, at the departure of human teachers with whom she has formed close relationships. She seeks to maintain close proximity to these teachers as they work with her, often simply sitting with an arm or leg draped across them. When they stay until evening she pulls them into the large nest that she builds and goes to sleep next to them. Nesting with others, of all sex classes, has been reported in wild Pan paniscus and is peculiar to this species (Kuroda, 1980). [Note that while pygmy chimpanzees have been reported nesting together, my inquiries indicate that the usual practice is for each adult to have its own nest.]

Similar sorts of attachment behavior toward humans are rarely observed in adult apes of other species (Yerkes and Yerkes, 1929). In instances where attachment to humans does occur in other ape species it is invariably preceded by a long period of rearing in which a human becomes a parental surrogate for the ape at a very early age (Patterson and Linden, 1981; Temerlin, 1975). Since Matata came to the project fully adult, with her own offspring to care for, her attachment to the humans around her is clearly not a result of human upbringing.Page 115 of

Print Edition Likewise, observations of her social behavior toward other pygmy chimpanzees housed with her at the field station prior to her inclusion in the Language Research Project revealed that she was well integrated into that group. She was the highest ranking female, the male’s favorite partner, and a competent mother of two young infants. She was, in general, the focus of group attention and evidenced frequent affiliative behaviors toward all the other individuals in the group.

As a result of these affiliative behaviors, which are extremely similar in form and content to those of humans, it has been possible to introduce new individuals who have no previous experience working with apes to Matata and Kanzi. The ready extension of affiliative behaviors towards new individuals stands in marked contrast to the behaviors displayed by [common chimpanzees who typically] . . . display considerable aggressive behavior toward strangers [in] . . . both male and female, and in both captive and wild environments . . .

Kanzi, like Matata, is extremely affiliative and socially responsive to human interaction and contact. He enjoys being carried around by his teachers and he initiates frequent carrying. Matata not only permits this, but on occasion even encourages Kanzi to go to others by detaching his hands and shoving him in the direction of another individual. This is not a sign of lack of interest in Kanzi, nor a sign of atypical maternal behavior in Matata. While Matata was housed with other pygmies at the field station she also allowed them to carry, play with, and discipline both Akili and Kanzi. She also encouraged these infants to go to other pygmy chimpanzees and retrieved them only when they appeared quite distressed. By one and a half years of age, Akili spent most of his time playing with other individuals in the group, particularly the adult male. He returned to Matata when he was hungry, sleepy, hurt (bumped his head, tripped, etcetera) or when she was moving from one area to another. Kanzi is following a similar pattern of strong attraction to other individuals, though in his case these other individuals are not pygmy chimpanzees, they are humans . . .

Interaction with others appears to be initiated primarily (though not entirely) by the strong attraction of young infants toward other individuals. On numerous occasions Kanzi hasPage 116 of

Print Edition leaped directly from Matata’s ventral surface onto the body of an approaching person . . .

As an infant, Kanzi is interested in exploring everything . . . Although Matata seems to be quite content to have others carry and entertain Kanzi for long periods, she is always keenly aware of his location at every moment . . .

Matata is tolerant of a wide variety of interactions between Kanzi and the teachers . . . [When a knife an experimenter was using accidently nearly cut Kanzi he] became furious, screaming and lashing out at the experimenter in attempts to bite. The experimenter, fearful (not of Kanzi), but that an attack from Matata would result, looked at Matata with an expression of dismay and pulled the knife back. Matata, having closely observed the entire set of events, simply pulled Kanzi to her and tried to quiet him even though Kanzi kept threatening the teacher. When the teacher reached out toward Matata, Matata hugged her and again tried to quiet Kanzi. Kanzi tried to bite the teacher even as his mother was hugging her. He remained angry for about 20 minutes.

It is quite surprising that Matata did not bite the experimenter in response to Kanzi’s screams. The Pan troglodytes [common chimpanzees] females observed by Savage (1975) would have responded to such an event (intended or not) with instant aggression.

The Pygmy Chimpanzee, Edited by Randall L. Susman, 1984, from Chapter 16: Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes by Dr E.S. Savage-Rumbaugh.

We can see that Matata’s world is above all a secure one and that she is cultivating that security in Kanzi. As a mother she appears to be exceptional in her ability to reassure and to cultivate trust. What she is reassuring Kanzi of, and teaching him to trust, is love. She has extraordinary trust that love, not hate, will prevail. The certainty in her behaviour is of the presence of love. An infant growing up in the common chimpanzee environment, where resentment and anger [are] readily aroused would not trust that it was not going to be attacked by others. In such circumstances love or harmony orPage 117 of

Print Edition integration (evasively referred to in this mechanistic study as affiliation) within the group would be tenuous at best. Matata’s world is one of extraordinary trust — of belief in and certainty of love — of security of self — of soundness. She is not from a divisive world, but a loving, integrative world and she is cultivating/nurturing that appreciation of love in Kanzi. She is love-indoctrinating him. Note that he, like the common chimpanzee, has not yet acquired a full appreciation of love or conscience.

Matata’s security and resulting integrativeness or affiliative behaviour is what made her popular and the focus of group attention. The others were recognising and favouring integrativeness. This is an example of self-selection.

I might mention here that unlike common chimpanzees, pygmy chimpanzees at times mate face to face and are in general more sexually active than common chimpanzees. Given they are becoming conscious this is not surprising. Consciousness would have brought a greatly enhanced capacity to reflect upon, savour and therefore enjoy pleasant sensations. The point is the increased sexual activity is not due to upset; it is not ‘sex’ as we know it. The perversion of the act of procreation emerged in Adolescentman as is explained on page 138.

Matata didn’t steal Kanzi from his mother out of cruelty, but because of love-indoctrination, which selects for more maternal mothers. In the end it produces a maternal instinct so strong it can become uncontrollable.

The proverbial devotion of wild primates to their young is really exemplary in mothers with the accumulated experience gained from having raised previous infants. That this successful care has benefited also from opportunities to observe other mothers of the group, has been demonstrated by the inefficient maternal behaviour, ranging to completely ignoring or even killing of the newborn, of captive mothers raised in total isolation. The urge to hold an infant, even though not their own offspring,Page 118 of

Print Edition seems to be irresistible to many female monkeys, according to the common occurrence of ‘baby snatching’ and adoption among captive macaques and other species. Indeed, there appeared recently a remarkable report of a wild female spider monkey seen to carry an infant howler monkey for several days until the latter died of starvation.

Adolph Schultz, The Life of Primates, 1969.

The fact that nurturing requires practice indicates that, intense an instinct as it already is in primates, it is a relatively recent development. The longer a behaviour occurs the more instinctive it becomes. Breathing for example has been practised by animals since they first appeared and is now totally instinctive, automatic or reflex. The potential to love-indoctrinate their infants accompanied the emergence of the primates’ ‘arms-freed-from walking’ arboreal lifestyle.

We can see that pygmy chimpanzees are far more advanced along the love-indoctrination path than common chimpanzees. Gorillas are too, but — I think we will discover — not quite as far advanced as pygmy chimpanzees. Interestingly, while pygmy chimpanzees depended on the safety of trees for the secure, threat-free environment needed to develop love-indoctrination, gorillas ‘chose’ physical size and great strength for that purpose. To quote Schultz again, the adult male gorilla is a remarkably peaceful creature, using its incredible strength merely in self-defence. The following extracts from Dian Fossey’s Gorillas in the Mist (1983) reveal the strong relationship between nurturing and integrativeness that is love-indoctrination:

Like human mothers, gorilla mothers show a great variation in the treatment of their offspring. The contrasts were particularly marked between Old Goat and Flossie. Flossie was very casual in the handling, grooming, and support of both of her infants, whereas Old Goat was an exemplary parent.

from Chapter 9Page 119 of

Print Edition

The effect of Old Goat’s exemplary parenting on Tiger (her son) is apparent:

Like Digit, Tiger also was taking his place in Group 4’s growing cohesiveness. By the age of five, Tiger was surrounded by playmates his own age, a loving mother, and a protective group leader. He was a contented and well-adjusted individual whose zest for living was almost contagious for the other animals of his group. His sense of well-being was often expressed by a characteristic facial ‘grimace.’

from Chapter 10

The growing cohesiveness (developing integration) brought about by loving mothers and protective leaders is love-indoctrination.

Dian Fossey’s account of the love-indoctrinated Tiger later in his life illustrates how nurtured love is required to produce the integrated group. It describes how the secure, integrative or loving Tiger tried to maintain integration or love in the presence of an aggressive, divisive gorilla after the group’s integrative silverback leader, Uncle Bert, had been shot by poachers.

The newly orphaned Kweli, deprived of his mother, Macho, and his father, Uncle Bert, and bearing a bullet wound himself, came to rely only on Tiger for grooming the wound, cuddling, and sharing warmth in nightly nests. Wearing concerned facial expressions, Tiger stayed near the three-year-old, responding to his cries with comforting belch vocalizations. As Group 4’s new young leader, Tiger regulated the animals’ feeding and travel pace whenever Kweli fell behind. Despondency alone seemed to pose the most critical threat to Kweli’s survival during August 1978.

Beetsme . . . was a significant menace to what remained of Group 4’s solidarity. The immigrant, approximately two years older than Tiger and finding himself the oldest male within the group led by a younger animal, quickly developed an unrulyPage 120 of

Print Edition desire to dominate. Although still sexually immature, Beetsme took advantage of his age and size to begin severely tormenting old Flossie three days after Uncle Bert’s death. Beetsme’s aggression was particularly threatening to Uncle Bert’s last offspring, Frito [son of Flossie]. By killing Frito, Beetsme would be destroying an infant sired by a competitor, and Flossie would again become fertile.

Neither young Tiger nor the aging female was any match against Beetsme. Twenty-two days after Uncle Bert’s killing, Beetsme succeeded in killing fifty-four-day-old Frito even with the unfailing efforts of Tiger and the other Group 4 members to defend the mother and infant. . . . Frito’s death provided more evidence, however indirect, of the devastation poachers create by killing the leader of a gorilla group.

Two days after Frito’s death Flossie was observed soliciting copulations from Beetsme, not for sexual or even reproductive reasons — she had not yet returned to cyclicity and Beetsme still was sexually immature. Undoubtedly her invitations were conciliatory measures aimed at reducing his continuing physical harassment. I found myself strongly disliking Beetsme as I watched his discord destroy what remained of all that Uncle Bert had succeeded in creating and defending over the past ten years . . .

I also became increasingly concerned about Kweli, who had been, only a few months previously, Group 4’s most vivacious and frolicsome infant. The three-year-old’s lethargy and depression were increasing daily even though Tiger tried to be both mother and father to the orphan.

Three months following his gunshot wound and the loss of both parents, Kweli gave up the will to survive . . .

It was difficult to think of Beetsme as an integral member of Group 4 because of his continual abuse of the others in futile efforts to establish domination, particularly over the indomitable Tiger . . .

Tiger helped maintain cohesiveness by ‘mothering’ Titus and subduing Beetsme’s rowdiness. Because of Tiger’s influence and the immaturity of all three males, they remained together.

from Chapter 11

Page 121 of

Print Edition In all ape species there is still a residual amount of uncontained sexual opportunism, such as dominance hierarchy (which orders and thus, to a degree, contains competition for mating opportunities) and infanticide such as mentioned above in the story of Tiger. The newly dominant male will often kill the offspring of his predecessor, bringing the mother back into season earlier than would otherwise occur, allowing the killer to mate and reproduce his genes more frequently. As mentioned, love-indoctrination was not at all easy to develop. It had to overcome some deeply embedded divisive behaviour. Developing love-indoctrination was like trying to swim upstream against a strong current to reach an island. The island was childhood, where love-indoctrination was complete and love had become instinctive. While struggling to reach the island of childhood, Infantman was often swept back downstream. Any breakdown in nurturing would lead to the appearance of divisive adults who had reverted to pre-love-indoctrination competitive, sexually opportunistic practices.

Impasses and difficult stages are natural features of Development as anyone who has tried to develop something knows. Evasive, mechanistic science, unable to acknowledge the purpose in existence of developing order, didn’t recognise the occurrence of impasses. If nature is not going anywhere, as the evolution theory maintains, then there can’t be any impasses or breaking through them. Unable to recognise impasses, science has not been able to explain stops and starts in nature, the ‘punctuated equilibrium’ evident in the fossil record. In this instance, the impasse was in integrating primates. Ideal nursery conditions were needed for love-indoctrination to develop, which explains why many primate species are still stranded in infancy. It also explains the fossil void or ‘missing link’ in the anthropological record of our forebears. We have as yet found no fossil evidence of our ape ancestor, Infantman.

Page 122 of

Print Edition To explain the missing link — 20 million years ago in warm, lush conditions, the forest-dwelling dryopithecines (the prototype apes) emerged. They thrived on fruit, soft leaves and shoots, and were as numerous as monkeys are today. Then about 15 million years ago the world’s climate began to cool and the lush forests began to shrink. By then the dryopithecines had developed into the more refined ramapithecines, which flourished between 14 and 8 million years ago and were spread widely across Africa, Asia and Europe in small, medium and large varieties. It is thought that further global cooling and resulting loss of forest habitat around 8 million years ago (when the plains animals of Africa started to proliferate) began to eliminate them. Apparently they were now sufficiently adapted to arms-free walking to begin to develop love-indoctrination, because those that were left almost certainly gave rise to existing ape species and to our ape ancestor, all of whom, to varying degrees, have been able to develop love-indoctrination.

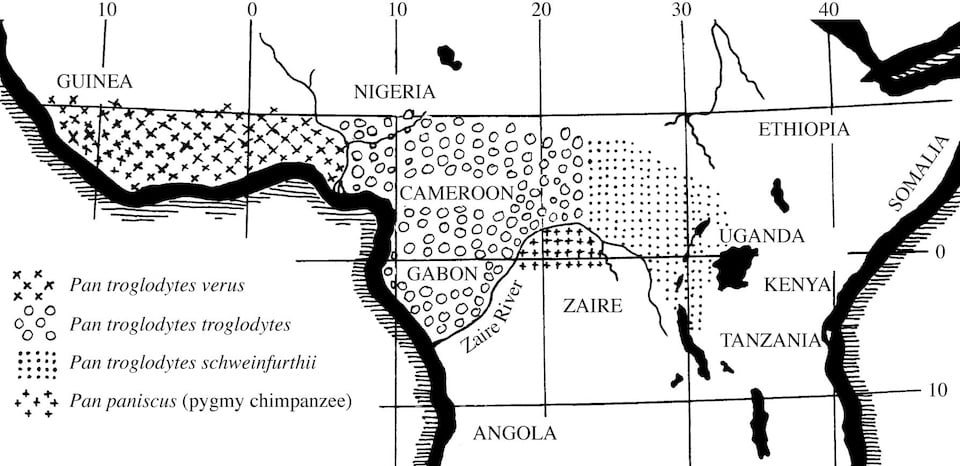

The fossil record from 8 to 4 million years ago is all but a blank for the apes and a complete blank for our ape ancestor. Ape species and numbers are few today, indicating that while they may be receptive to love-indoctrination they are not well adapted to current environmental conditions. Given their rarity today and (presumably) over the past 8 million years, it is not surprising that fossil evidence of them is scarce, but why is there nothing of our ape ancestor? Now that we know how ideal nursery conditions must be to support love-indoctrination, we can appreciate that evidence of our ape ancestor must be even scarcer than that of the other apes. Chimpanzees illustrate the predicament perfectly. Today we have only four varieties of chimpanzee, none of them numerous, with only one, the pygmy chimpanzee, living in an area — and it’s only a small area — well suited to developing love-indoctrination. We can imagine that in the far future, fossil evidence of chimpanzees will be even scarcer than it is today, and that of pygmy chimpanzees scarcest of all.

Page 123 of

Print Edition

Equatorial Africa,

showing distribution of the four varieties of chimpanzee.

After a drawing in Adolph Schultz’s, The Life of Primates, 1969.

After reading about nurturing among gorillas and chimpanzees, we can appreciate the difficulty we have had in acknowledging its importance in development. Many mothers will feel awkward as they read this material, because it confronts them with their inability to nurture their children as much as they would like. The truth is, no mother has ever been able to love her child as much as all mothers did before the human condition emerged. It bears repeating that now we can explain/justify our inadequate nurturing, we can safely confront the truth of the importance of nurturing. I should stress that the difference in nurturing ability among apes is due to incomplete love-indoctrination whereas in humans it was caused by our preoccupation with the battle to find understanding.

Page 124 of

Print Edition

Photograph by Manny Rubio

Matata with her adopted son, Kanzi

As mentioned earlier, the pygmy chimpanzee is on the threshold of childhood; in fact I think we could consider Matata a living example of what Childman was like. (Note: it is not of great significance whether pygmy chimpanzees are our genetically closest living relatives — humans and apes Page 125 of

Print Edition almost certainly all descended from the ramapithecines — what is of interest is that pygmy chimpanzees are our psychologically closest living relatives.) Given that pygmy chimpanzees are rare and endangered, that we can now appreciate how loving and conscious they are and see how much they can reveal about our own time in ‘the Garden of Eden’, a concerted effort must be made to protect them. I would like the World Transformation Movement to establish a fund to help protect them and to make an unevasive study of them.

It is appropriate to point out again that infancy, childhood and adolescence are the evasive terms we’ve used to describe the stages of the emergence of understanding. Infancy is characterised by self-awareness, childhood by self-confidence and adolescence by self-understanding or identity search. Adolescence was when the upset human condition developed, the stage humanity is about to leave for the adult stages of self-implementation, self-fulfilment and self-maturation.

Once a species has completed infancy, the other stages will follow naturally. While the rate of development may vary through childhood and adolescence, unlike what happened in infancy, development through these stages is inevitable and (overall) rapid, which is why there are no living examples of the australopithecines or the stages that preceded Homo sapiens sapiens. In adolescence, the first to descend the exhaustion curve (Fig.3) always replaced the less advanced. Upset has been replacing innocence for 2 million years, occasionally through physical conflict but mostly by the more innocent finding themselves unable to accept and cope with the new reality, the new level of compromise of the ideals.

Now Abel kept flocks, [stayed close to nature and innocence] and Cain worked the soil [became settled and began the discipline and drudge of searching for knowledge] . . . Cain [became] very angry, and his face was downcast [depressed] . . . [and] Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him.

The Bible, Genesis 4:2,5,8.

Page 126 of

Print Edition The dreadful journey through adolescence has made us more and more callous, which means dead in intellect and soul. Thankfully, it is over.

We can see that love-indoctrination has been the most important process in humanity’s development. It gave us our conscience and liberated conscious thought in us.

Another consequence of love-indoctrination was that it freed our hands to hold tools and implements and for an almost endless list of other applications. The more love-indoctrination developed and the longer infants were kept in infancy and the more they had to be held, the more we had to stay upright in order to hold them. This freedom of our hands from walking proved extremely useful later when the intellect needed to assert itself, because it could direct the Page 127 of

Print Edition hands to manipulate objects. A fully conscious mind in a whale or a dog would be frustrated by its inability to implement its understandings.

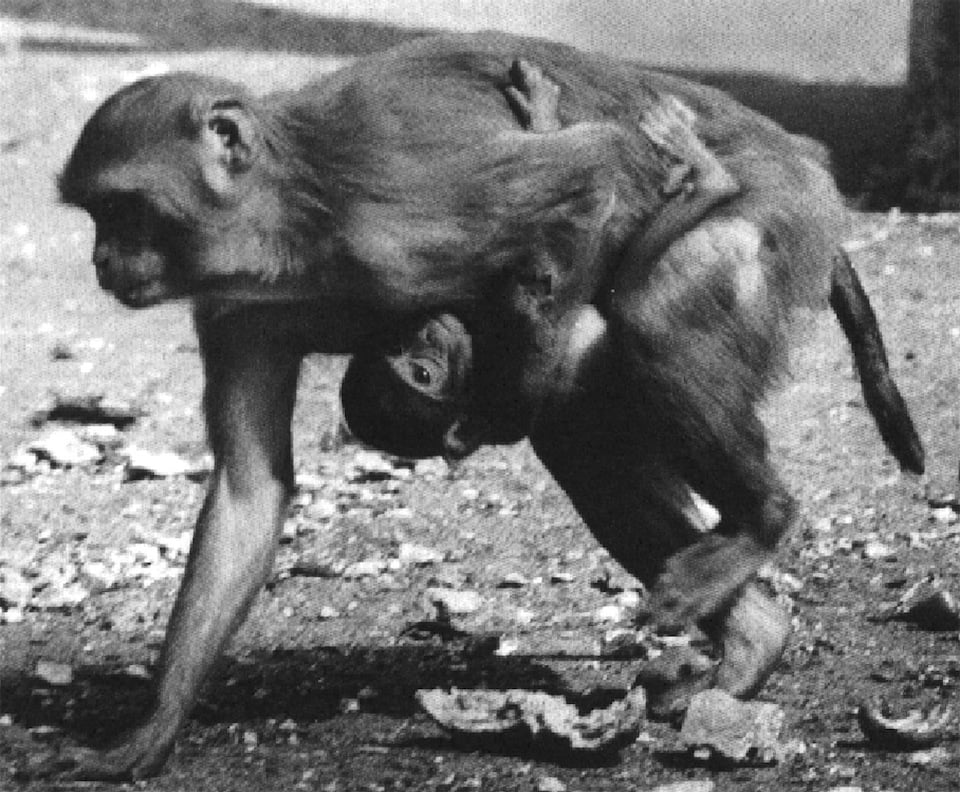

Photograph by Wolfgang Suschitzky

Rhesus monkey with infant. This picture illustrates the difficulty of

carrying an infant and suggests the reason for bipedalism.

The following transcript provides some indication of the leisure, fellowship and friendliness that existed among humans during humanity’s integrative childhood.

Q: What does your average study day involve?

A: We usually get up before dawn and go out to the nests where the pygmy chimpanzees have slept. We are then there when they get up in the morning. They usually get up very slowly and if it’s raining, they like to stay in bed for a long time, which I can understand. They will then often head for a fruit tree that’s nearby and they’ll have a big feeding bout first thing in the morning before they settle down for a long rest or play period [love-indoctrination period] in mid-morning to midday. They’ll then start to travel more, maybe to visit some other fruit trees and this is often when it becomes difficult to follow them. Although if they’re moving short distances they go through the trees, when they’re going to go a long way they come down to the ground and move very fast and we often end up losing the animals when trying to follow them, but we also know that they know that we’re there. The animals that we’re most used to following have now got to the stage where they’ll come to the ground and start moving off and we move off after them. But we lose them and don’t know which way to head, so we’ll sit down and wait for them to call and several times now I’ve been sitting waiting for the animals to call to know which way to go and I’ll turn around and there’s this face peering at me through the underbrush and it’s the pygmy chimps come to see why I’ve stopped following them.

Dr Frances White (interviewed by Miles Barton), BBC Science Magazine, 1990.