Beyond The Human Condition

Page 19 of

Print Edition Introduction

HERE on Earth, some of the most complex arrangements of matter in the known universe have come into existence. Life with its incredible diversity and richness developed.

By virtue of our mind, the human species must surely be the culmination of this grand experiment of nature that we call life. As far as we can detect, we are the first organism to have developed the ability to think and reflect upon itself. In this world, ravaged as it is by strife, it is easy to lose sight of the utter magnificence of what we are. The human mind must be nature’s most astonishing creation.

One of the greatest demonstrations of our intellectual brilliance was sending three of our kind, in a machine of our own invention, to the Moon and back.

How far we have come!

But what a mess our world is in!

Despite the tremendous successes science has brought us, our plight only seems to be worsening in terms of human happiness and the Earth’s well-being. Better forms of management such as better laws, better politics, better economics and better self-management such as new ways of disciplining, organising, or even transcending our upset natures have all Page 20 of

Print Edition failed to end our destructiveness and bring us peace and happiness. The recent war in the Persian Gulf, with its real threat of nuclear and chemical devastation, its scenes of torture, massacre and environmental destruction, has convinced many that nothing has changed for the better.

As we approach the twenty-first century man is starting to realise that the underlying problem is psychological. We are beginning to suspect that war, overpopulation, environmental degradation, resource depletion, species extinction, drugs, starving millions, crime, family breakdown, despair and even sickness are merely symptoms of a deeper problem: our often destructive, insensitive, egotistical and aggressive nature.

Environmental issues dominate our concern but surely we are focusing on the symptoms not the cause of the problem. The real issue is ourselves, our upset state or nature or condition. The real frontier, challenge and adventure before us now is not outer space, as we tend to believe, but inner space — the human condition no less.

. . . we need a new kind of explorer, a new kind of pathfinder, human beings who, now that the physical world is spread out before us like an open book . . . are ready to turn and explore in a new dimension.

Laurens van der Post, The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955.

The time has come — and it is now a matter of urgency — to switch our attention from the physical to the psychological and to grapple with the crux problem, that greatest of all paradoxes, the riddle of human nature. If the universally accepted ideals are to be cooperative, loving and selfless — they have been accepted by the great civilisations as the basis for their constitutions and laws and by the founders of all the great religions as the basis of their teachings — why are we competitive, aggressive and selfish? What is the reason for our divisive nature?

Page 21 of

Print Edition

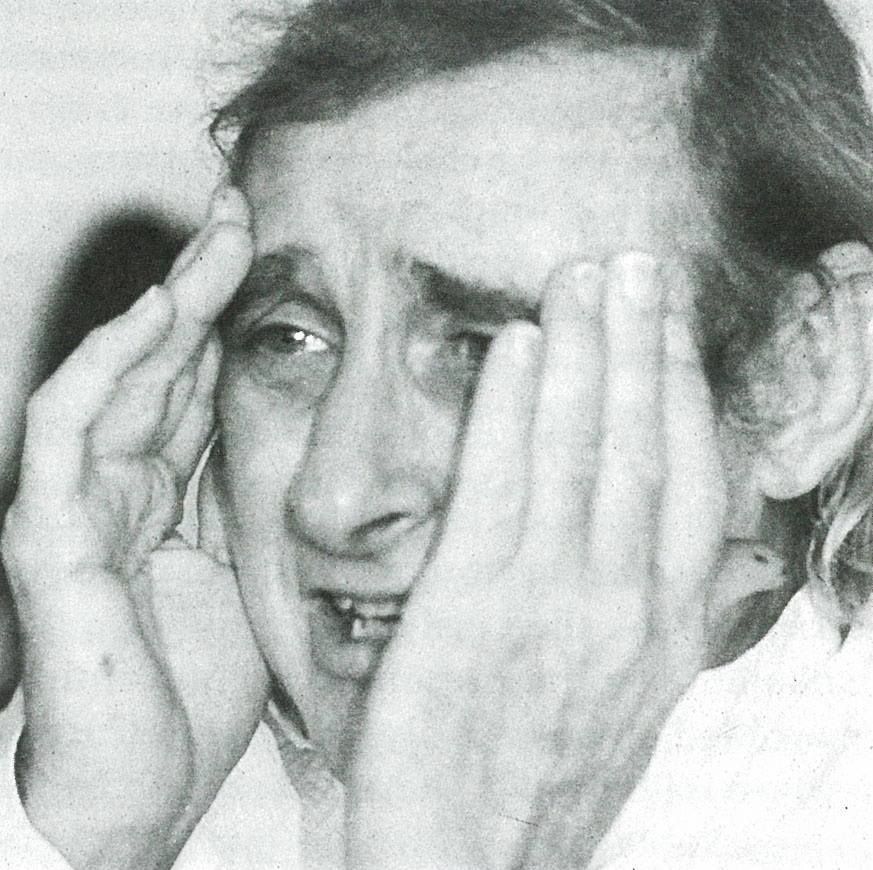

Comedian Spike Milligan, interviewed by John Newton.

Newton: Bob Ellis — the Australian playwright — once said ‘humour is the sparkle on the deep river’.

Milligan: That’s quite beautiful . . . the sparkle on the deep river, yes!

Newton: That being the case, can we use humour to clean up the deep river? Or must the poor clown, as you said earlier, stand by and watch as the human race rushes towards annihilation?

Milligan: Tell ‘em jokes as they go by. That’s the awful part of it. I don’t think laughter can save us, not at all. It is a serious business. We can laugh during it, at it. The world has never reached this hour before. The politicians are totally unprophetic. They run the world politically, believing it to be the right thing, and it’s turned out to be a total disaster. And they don’t know what to do.

Text and Photo: The Bulletin, December 26, 1989.

Page 22 of

Print Edition The world is hurtling to catastrophe: from nuclear horrors, a wrecked ecosystem, 20 million dead each year from malnutrition, 600 million chronically hungry . . . All these crises are man made, their causes are psychological. The cures must come from this same source; which means the planet needs psychological maturity . . . fast. We are locked in a race between self destruction and self discovery.

Australian journalist and author Richard Neville, The Sydney Morning Herald, Good Weekend supplement, October 14, 1986.

The purpose of this book is to unlock the riddle of human nature; to answer this question of questions of the origin of, or reason for, our so-called evil side.

The explanation to be presented is confronting — that cannot be avoided — but it is also liberating. Paradoxically, and this is why it is liberating, the answer dignifies humans in the most remarkable way. It lifts the burden of guilt from humanity. It exonerates us and restores our love of ourselves, our kind and all creation. It allows us to heal the wounds we have inflicted on the planet, on one another and on ourselves. It provides us with the key to freedom from our upset state or condition. It brings us understanding of ourselves.

Human nature is not the immutable state we have often considered it to be; rather it is the symptom of a condition — the human condition — that will disappear now that the condition is relieved.

______________________

The eternal question has been why ‘evil’? Why are we humans capable of extreme greed, hatred, brutality, rape, murder, war? Are we essentially good, and if so, what is the cause of our evil, destructive, insensitive and cruel side? Does our inconsistency with the universally accepted ideals of love, cooperation and selflessness mean we are essentially bad? Are we a flawed species, a mistake — or are we possibly divine beings? Life has always been a constant struggle to understand the conflicting forces within us.

Page 23 of

Print Edition Insecure in our goodness and aware of our badness, humanity has through the ages searched for a clear understanding of this great paradox. Neither philosophy nor science has been able to give a clarifying explanation. Religious assurances such as ‘God loves you’ don’t explain why we are lovable. Lacking clear understanding, we still carry a burden of unhappiness within ourselves.

When the stars threw down their spears

And watered heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

William Blake, The Tyger, c 1789—93.

If we call the embodiment of the ideals that sustain our society ‘God’ then we’re a ‘God fearing’ species, condemned by the ideals, in fear and insecurity. Our human predicament, or condition, is that we have had to live with an undeserved sense of guilt.

Whenever we have tried to understand why there was evil in the world and indeed in ourselves we couldn’t find an answer and eventually had to put the question out of our minds. We have coped with our sense of guilt by blocking it out, sensibly avoiding the whole depressing issue of our inconsistency with the ideals.

So skilled are we at overlooking the hypocrisy of human life and blocking out the question it raises of our guilt or otherwise, when the hypocrisy does appear we often fail to recognise it or the question it raises. In fact we couldn’t afford to mention the human condition until it could be solved. While ‘human nature’ appears in dictionaries, ‘human condition’ doesn’t.

Where adults now fail to recognise the paradox of human behaviour, children in their naivety still do. They ask, ‘Mummy why do you and Daddy shout at each other?’ and ‘why are we going to a lavish party when that family down the road is poor?’ and ‘why do men kill one another?’ and ‘why isPage 24 of

Print Edition everyone unhappy and preoccupied?’ and ‘why are people so artificial and false?’.

The truth is the hypocrisy of human behaviour is all about us. Two-thirds of the people in the world are starving while the rest bathe in material security and go on seeking still more wealth and luxury.

With regard to the hypocrisy of life, in 1969 in the southern states of the USA there was a problem with busing — negroes weren’t allowed on buses designated for whites — and I remember at that time someone saying: ‘We can get a man on the moon, but we still can’t get a negro on a bus!’

Bob Smith, a supporter of the World Transformation Movement.

Humans can be heartbroken when they lose a loved one but are also capable of shooting one of their own family. We have dived into raging torrents to help others without thought of self but have also molested children. We have tortured one another but have also been so loving we regularly gave our lives for others. A community will pool their efforts to save a kitten stranded up a tree and yet humans will also eat elaborately prepared dishes featuring endangered animals (Time magazine, April 8, 1991). They have been sensitive enough to create the beauty of the Sistine Chapel, yet so insensitive as to pollute their planet to the point of threatening their own existence.

Good or bad, loving or hateful, angels or devils, constructive or destructive, sensitive or insensitive, what are we? Throughout our history, we’ve struggled to find meaning in the awesome contradictions of the human condition. We desperately need a clear biological understanding of ourselves, understanding that will liberate us from criticism, lift the burden of guilt, give us meaning, bring peace to our minds and lead us to achieving our psychological maturity as a species. Catch-phrases like ‘self-esteem’ and ‘human potential’ stress this yearning for self-justification and self-realisation. To adapt a famous expression of Benjamin Disraeli’s,Page 25 of

Print Edition stalled halfway between ape and angel is no place to stop.

What then is the answer to this question of questions; this problem of good and evil that defies us, or is there no answer?

The problem of the origin and universality of sin . . . is probably one of those problems which the human mind can never satisfactorily answer.

The Bible Reader’s Encyclopedia and Concordance (under ‘sin’).

[In his book Grist for the Mill (1977), Ram Das, when asked] why did we [fall from grace] in the first place? [replied] that is the question which is the ultimate question [and that] your subject-object mind can’t know the answer to that question.

Before Darwin, the origin of the variety of life on Earth seemed inexplicable. And yet his idea of natural selection was so simple that a contemporary, Thomas Henry Huxley, responded, How extremely stupid of me not to have thought of that!

While the crux question of our time of good and evil has always seemed inexplicable, in fact it too has an amazingly simple answer.

______________________

What follows is a journey that explores the biology of the human condition from a beginning that preceded conscious thought. It traces human development through to the twentieth century and looks at the source of our current distress. Though the ideas are in essence quite simple, their challenging nature can make them difficult to grasp. To aid understanding, analogies and illustrations have been used, which though simplistic, have already proved effective.

We begin with an analogy using migrating birds, which helps us to understand the essence of the human condition. Don’t worry about whether storks eat apples or talk — that is irrelevant — the purpose of this little story is to consider what happened when two conflicting forms of thinking had to share the same brain.