Beyond The Human Condition

Page 27 of

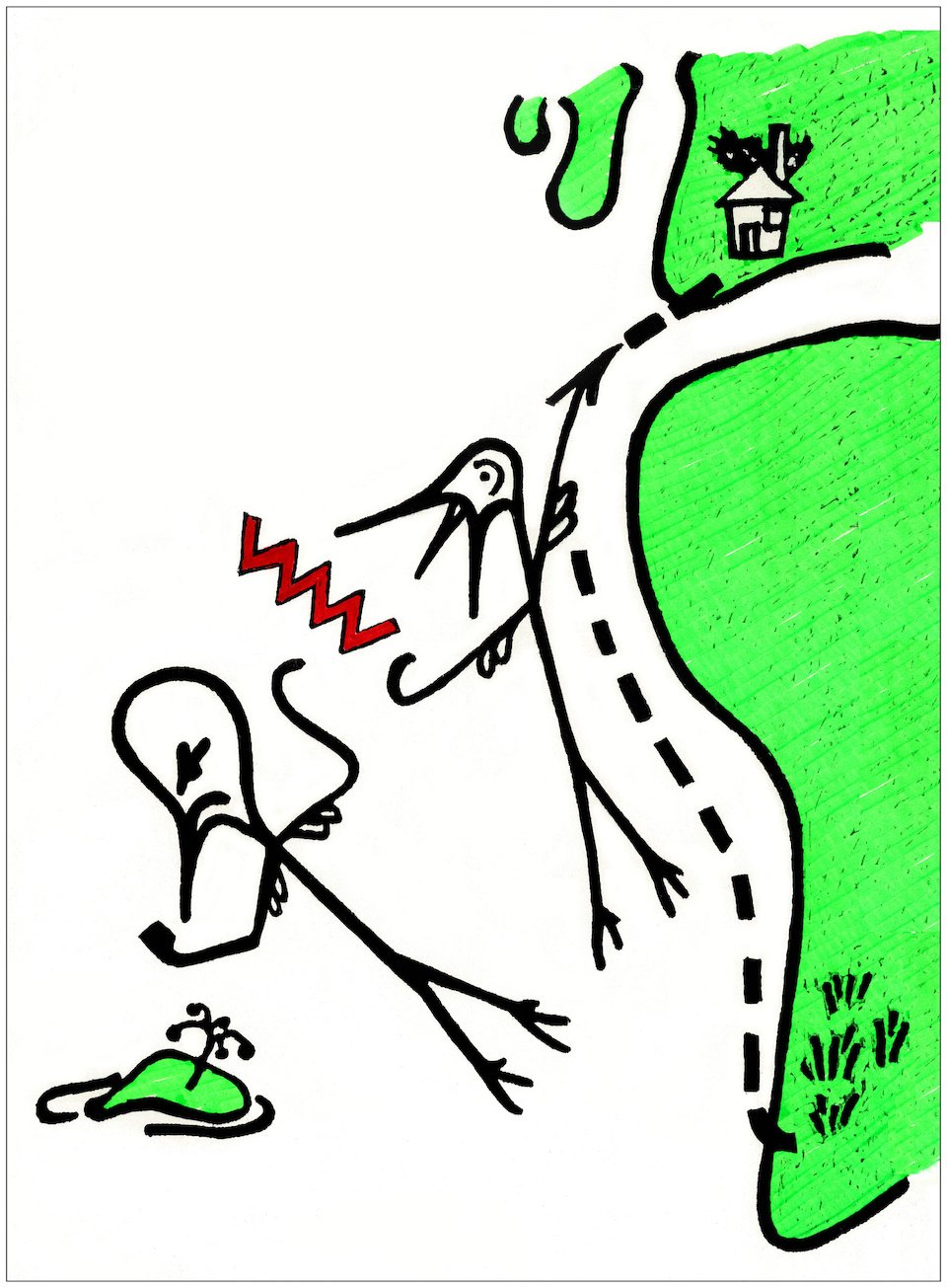

Print Edition 1. The Story of Adam Stork

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © Fedmex Pty Ltd 1991

MANY bird species are perfectly orientated to instinctive migratory flight paths. Every winter, without ever ‘learning’ where to go and without knowing why, they fly to warmer feeding grounds and return in summer to breed.

Consider a flock of migrating storks returning from southern Africa to their summer breeding places on the roof-tops in Europe.

Suppose that in the instinct-controlled brain of one of them (let’s call him Adam) we place a fully conscious mind. As he flies northwards, he sees an island off to the left with apple trees laden with ripe fruit.

Using his newly acquired conscious mind, Adam thinks, ‘I should fly down and munch on some apples’. It seems reasonable but he can’t know if it is a good decision or not until he’s tried it. He’s breezed along, all his stork life, on instinct. Being the only stork with a conscious mind, he can’t consult the others and, having just acquired a conscious mind himself, he has as yet no knowledge of what are correct and incorrect understandings.

For his new thinking mind to make sense of the world, he has to learn by trial and error. Having to start somewhere, he decides to carry out his first grand experiment in self-management by flying down to the island and eating some of those delicious apples.

Page 28 of

Print Edition But it’s not that simple. As soon as he deviates from his migratory course and heads down towards the island, his instinctive self tries to pull him back on course. In effect, it criticises him for going off course and doesn’t want him to search for understanding.

Adam is in a dilemma. If he obeys his instinctive self and flies back on course, he will be perfectly orientated but he’ll miss out on the apples. And he’ll never learn if it was the right thing to do or not.

All the messages he’s receiving from within tell him that to obey his instincts is good. But there’s a new message of disobedience, a defiance of instinct. Going to the island will bring him apples and understanding, but it will also make him feel bad.

Uncomfortable with the criticism his conscious mind or intellect receives from his instinctive self, Adam’s first response is to ignore the apples and fly back on course. This makes his instinctive self happy and wins approval from the other storks. Not having conscious minds, they are innocent, unaware or ignorant of a conscious mind’s need to search for knowledge. They are obeying their instinctive selves by following the flight path past the island.

But, flying on, Adam realises he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later he has to find the courage to master his conscious mind by carrying out experiments in understanding. (It is only by trial and error or by learning from others’ experiences that any of us learn to understand.)

So Adam decides to continue with his experiments in self-management. This time he thinks, ‘Why not fly down to the island and have a rest?’ Not knowing any reason why he shouldn’t, he goes ahead with the experiment. But again his instinctive self criticises him for going off course.

This time he defies the criticism and perseveres with his experiments in self-management. But it means he has to live with the criticism. Immediately he is condemned to a state of upset. A battle has broken out between his instinctive self, Page 29 of

Print Edition perfectly orientated to the flight path, and his emerging conscious mind, which needs to understand why it’s the correct path to follow. His instinctive self is perfectly orientated, but he doesn’t understand that orientation.

What Adam needs to do is appease his innocent, instinctive self with some vital information. He could begin with the difference between a gene-based learning system and a nerve-based learning system. He should explain that the genetic learning system, which gave him his instinctive orientation, is a powerful learning tool. Over generations it is able to adapt species to new circumstances. But he should also explain that only the nerve-based learning system can learn to understand cause and effect. The problem is that he knows none of this. It is going to take humanity 2 million years to achieve that understanding. In the meantime the battle within him continues at a furious pitch.

______________________

To see how instincts are only orientations and not understandings we could consider how instincts are acquired.

The genetic make-up of birds includes a response to the Earth’s magnetic field and other factors useful in direction finding. And though they are all similar, their response varies slightly just as they vary slightly in their looks.

Suppose that while the storks were in Africa a volcano erupted in their flight path off the coast of Africa, forming a large island mountain too high to fly over.

When the storks reach the island on their migration, their differing genetic make-up causes some to fly east around it and others to fly west. The latter perish because that route happens to take them too far around the inhospitable island. The others survive and perpetuate the genetic make-up that makes them fly east around the island.

Species can be genetically adapted, or oriented to new circumstances but orientation is not understanding.

Page 30 of

Print Edition Adam Stork needed to be able to explain that a nerve-based learning system, being memory-based, can understand cause and effect. Once you can remember past events, you can compare them with current events and identify common or regularly occurring experiences. This knowledge of, or insight into, what has commonly occurred in the past enables you to predict what is likely to occur in the future and to adjust your behaviour accordingly.

A nerve-based learning system can associate information, it can reason how experiences are related. It can learn to understand and become conscious of the relationship of events through time. A genetic learning system on the other hand can’t become conscious.

______________________

When the fully conscious mind emerged, it wasn’t enough for it to be orientated by instincts. It had to find understanding to operate effectively and fulfil its great potential to manage life. Tragically the instinctive self didn’t ‘appreciate’ that need and ‘tried to stop’ the mind’s necessary search for knowledge, that is, its experiments in self-management. A battle between instinct and intellect developed.

(All underlinings in quotes and text are my emphasis.)

I spoke to you earlier on of this dark child of nature, this other primitive man within each one of us with whom we are at war in our spirit.

Laurens van der Post, The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955.

[Origen argued that] at the beginning of human history, men were under supernatural protection, so there was no division between their divine and human natures: or, to rephrase the passage, there was no contradiction between a man’s instinctual life and his reason.

Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines, 1987.

Page 31 of

Print Edition To refute the criticism from his instinctive self, Adam Stork needed to know the difference in the way genes and nerves process information. But when he diverted to the apple tree, he was only taking the first tentative steps in the search for knowledge. He was in a catch 22 situation. In order to explain himself, he needed the understanding he was setting out to find. He had to search for understanding without the ability to explain why. He couldn’t defend his actions. He had to live with criticism from his instinctive self. Without defence, he was insecure in its presence. He had to live with a sense of guilt that wasn’t justified.

What could he do? If he abandoned the search he’d get short-term relief, but the search still had to be undertaken.

All he could do was retaliate against the criticism, try to prove it wrong or simply ignore it, and he did all of those things. He became angry towards the criticism. In every way he could he tried to demonstrate his worth — to prove that he was good and not bad. And he tried to block out the criticism. He became angry, egocentric and alienated or, in a word, upset.

London, 1970: At a public lecture I listened to Arthur Koestler airing his opinion that the human species was mad. He claimed that, as a result of an inadequate co-ordination between two areas of the brain — the ‘rational’ neocortex and the ‘instinctual’ hypothalamus — Man had somehow acquired the ‘unique, murderous, delusional streak’ that propelled him, inevitably, to murder, to torture and to war.

Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines, 1987.

Arthur Koestler explains his ‘inadequate co-ordination’ theory more fully in his prologue to Janus: a summing up, 1978, in which he also says Thus the brain explosion gave rise to a mentally unbalanced species in which old brain and new brain, emotion and intellect, faith and reason, were at loggerheads.

Page 32 of

Print Edition Adam was in an extremely unpleasant position. He had to endure being upset until he found the defence or reason for his mistakes. Suffering upset was the price of his heroic search for understanding.

A sadder and a wiser man . . .

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of The Ancient Mariner, 1797.

Consequently, we can see that he was good while he appeared to be bad. Upset was inescapable in the transition from an instinct-controlled state to an intellect-controlled state. His uncooperative or divisive aggression and his egocentric efforts to prove his worth and evade criticism became an unavoidable part of his personality. Such was his predicament, and such has been the human condition.

The paradox of the human condition was that while we appeared bad we always believed that we were good. Our hope and faith was that one day we would be able to explain this contradiction, liberating ourselves from our sense of guilt.

______________________

OK, so the only way that most of us humans can fly is by making a booking with an airline. We don’t have a great deal in common with storks, but the point is that all animals, including humans, have an instinctive self. Carl Jung called our common, or shared by all, instincts ‘the collective unconscious’.

Jung regards the unconscious mind as not only the repository of forgotten or repressed memories, but also of racial memories. This is reasonable enough when we remember the definition of instinct as racial memory.

International University Society’s Reading Course and Biographical Studies, Volume 6, c 1940.

Page 33 of

Print Edition The Tao acts through Natural Law . . .

From ancient times to the present,

Its name ever remains,

Through the experience of the Collective Origin.

From the 21st passage of Tao Te Ching, attributed to Lao Tzu (604—531 BC), as translated by R.L. Wing.

While humanity wasn’t orientated to migratory flight paths, we still must have had instinctive orientations to guide us before we acquired consciousness. Importantly, then, what was our main instinctive orientation? Perhaps the answer can be found in the photograph below.

Page 50-51 of

Print Edition

Do you get the feeling you are looking at a single entity rather than 16 individual gorillas? (Yes, there are 16.) There’s no distrustful personal space between them; they’re harmonious, in fact so secure in each other’s presence that there are no furtive sideways glances, they are all looking outward. In their oneness they take each other for granted. Ants in their cooperative or integrated nests and bees in their hives do the same. There’s no insecurity or divisiveness.

Certainly studies have shown that there is still some uncooperative or divisive behaviour among gorillas, but having lived with unjust criticism of our own divisive behaviour, aren’t we likely to stress any divisiveness in other animals (dumb and innocent as they are) to make us feel better? The films King Kong (1933) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) seem to wildly exaggerate aggression in gorillas. One way Adam Stork coped with unjust criticism was by evading it. It’s understandable that we would evade recognition of cooperative integrative behaviour in other animals if it represented unjust criticism of our own divisive nature.

I confess freely to you, I could never look long upon a monkey without very mortifying reflections.

William Congreve in a letter to Jean Baptiste Denis, 1695. Mentioned in Shirley C. Strum’s book (about baboons), Almost Human, 1987.

Page 34 of

Print Edition The ‘aggressive’ label belongs to humans rather than gorillas. In the 1979 BBC television series Life on Earth, David Attenborough is seen on a hillside in Rwanda embraced by a band of gorillas. In the only instance in 13 episodes that he brings humans into the dialogue, he says: If there was any possibility of escaping the human condition and living another animal’s life it must be as a gorilla . . . It seems very unfair that man should have chosen the gorillas to represent all that is violent, which is not what the gorilla is — but we are.

Dian Fossey (who wrote Gorillas in the Mist, 1983) was impressed and inspired by their cooperative harmony, their sheer unity or love.

[After being approached and touched by a male silverback mountain gorilla in Rwanda’s Volcano Park forest] I felt a kind of unspecified glow, something within that was very much like love, and it came to me then that for the past fourteen years Dian Fossey had literally lived in that glow.

Tim Cahill, A Wolverine is Eating My Leg, 1990.

If gorillas are similar to our ape ancestors, perhaps this photograph suggests a time before upset, when there was no anger, egocentricity or alienation.

The great frontier between the two types of mentality is the line which separates non-primate mammals from apes and monkeys. On one side of that line behaviour is dominated by hereditary memory, and on the other by individual causal memory . . . The phyletic history of the primate soul can clearly be traced in the mental evolution of the human child. The highest primate, man, is born an instinctive animal. All its behaviour for a long period after birth is dominated by the instinctive mentality. . . . As the . . . individual memory slowly emerges, the instinctive soul becomes just as slowly submerged . . . For a time it is almost as though there were a struggle between the two.

Eugène Marais, The Soul of the Ape, written in the 1930s, published in 1969.

Page 35 of

Print Edition In the chapter How We Acquired Our Conscience it will be explained how humanity acquired a perfect instinctive orientation to cooperative or integrative behaviour. Before introducing that explanation it is necessary to remove our need to evade certain truths. At this point the objective is to examine the possibility (as suggested by the photo of the gorillas) that humans have a cooperative past.

If our original instinctive self or soul, the voice of which is our conscience, was perfectly orientated to the ideals of being cooperative or integrative when our fully conscious intellect emerged, our intellect would have had to know why cooperative, integrative behaviour was important. But tragically, when our intellect began its search for understanding, our conscience unjustly criticised it.

. . . our nature [conscience — is] . . .

A sharp accuser, but a helpless friend!

Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, Epistle II, 1733.

[can] innocence, the moment it begins to act . . . avoid committing murder [?]

Albert Camus, L’Homme Révolté, 1951 (Published in English as The Rebel, 1953).

Our instinct had no sympathy for the search for knowledge. If it had had its way the search would have stopped. We had no choice but to defy our conscience and suffer its unjust, and thus upsetting, criticism.

It’s an explanation that parallels the story of Adam and Eve. Genesis (1:27) tells us that we were created . . . in the image of God. We were once perfectly orientated to cooperative, selfless, loving ideals. Then Adam and Eve ate the fruit of the tree of knowledge in order to be like God knowing (Genesis 3:5). In short, we went in search of understanding.

Having eaten the forbidden fruit Adam and Eve were in deep trouble. We’re told they were evil and cast out of Eden. When we went in search of understanding, our upset naturePage 36 of

Print Edition emerged. Life was no longer a Garden of Eden, but a quest for conscious understanding of our purpose.

Take the wonderful story of Adam and Eve, the Garden, the apple, and the snake . . . Is it a story of our fall from grace and alienation from our environment? Or is it a story of our evolution into self-consciousness . . . ? Or both? It is also a story of human greed and fear and arrogance and laziness and disobedience in response to the call to be the best we can be.

M. Scott Peck, The Different Drum, 1987.

One semi-plausible theory [to explain our loss of sensitivity] is Julian Jaynes’s idea of the bicameral mind [see Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, 1976]. According to Jaynes, humankind was once possessed of a mystical, intuitive kind of consciousness, the kind we today would call ‘possessed’; modern consciousness as we know it simply did not exist. This prelogical mind was ruled by, and dwelled in, the right side of the brain, the side of the brain that is now subordinate. The two sides of the brain switched roles, the left becoming dominant, about three thousand years ago, according to Jaynes; he refers to the biblical passage (Genesis 3:5) in which the serpent promises Eve that ‘ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil’. Knowing good and evil killed the old radiantly innocent self; this old self reappears from time to time in the form of oracles, divine visitations, visions, etc. — see Muir, Lindbergh, etc. — but for the most part it is buried deep beneath the problem-solving, prosaic self of the brain’s left hemisphere. Jaynes believes that if we could integrate the two, the ‘god-run’ self of the right hemisphere and the linear self of the left, we would be truly superior beings.

Rob Schultheis, Bone Games, 1985.

The demise of the imaginative right side of our brain is explained on page 106.

Throughout our history, theologians, writers, poets and artists have described and represented our predicament (asPage 37 of

Print Edition the story of the Garden of Eden does so well), but they couldn’t explain it. And only explanation could clarify the question of our guilt. We needed clear biological understanding.

The discipline of science had to be developed. With it came all the details, or mechanisms, of our world. Science made possible a clarifying, biological explanation of why we became upset. It was only in this century that science achieved understanding of the gene and nerve based learning systems, with which we at last have the means to resolve the riddle of human nature. We can explain that there were two different learning systems, each of which needed to learn about integration in its own way. The result was our upset state or condition. Knowing that genes can orientate but only nerves can understand explains our ‘mistakes’. We can now see that we weren’t bad or guilty after all, which frees us from our sense of guilt and ends the human condition.

. . . how can there ever be any real beginning without forgiveness?

Laurens van der Post, Venture to the Interior, 1952.

At last we can answer the question of questions that William Blake asked in such simple words in The Tyger, quoted in the Introduction. Yes, he who made the lamb did make thee. We are not evil beings. We are part of God’s plan after all. We are relevant/meaningful/worthy. We can love ourselves and each other now.

Compassion leaves an indelible blueprint of the recognition that life so sorely needs between one individual and another; one nation and another; one culture and another. It is also valid for the road which our spirit should be building now for crossing the historical abyss that still separates us from a truly contemporary vision of life, and the increase of life and meaning that awaits us in the future.

Laurens van der Post, Jung and The Story of Our Time, 1976.

Page 38 of

Print Edition To find understanding of our instinctive ideals, we had to battle with the ignorance of our instinctive self or soul. Upset was unavoidable. Our predicament was summed up in The Man of La Mancha. We had to be prepared To march into Hell for a Heavenly cause. We had to lose ourselves to find ourselves. Christ asked, What good is it for a man to . . . forfeit his soul? (The Bible, Mark 8:36). The answer is we had to forfeit our soul to find knowledge.

Unable to explain why we had to make mistakes, we became aggressive towards the unjust criticism. We tried to prove it wrong and to block it out of our minds. We became angry, egocentric and alienated. Upset or ‘sin’ was born. As well we sought material comfort and self-aggrandisement to give ourselves the glory we knew we deserved, glory denied us by our soul’s ignorance of our true or greater goodness.

Having become upset because we couldn’t defend our actions, it follows that finding the defence eliminates upset. Understanding our true goodness is the key to real peace on Earth. Adam and Eve were heroes, not villains. Humanity was unjustly banished from the Garden of Eden. We lost innocence because we appeared bad and couldn’t explain that we weren’t.

While our instinctive self or soul became perfectly orientated to the cooperative ideals it didn’t understand those ideals. When our conscious mind went in search of understanding of those ideals our instinctive self criticised the search which made us angry, egocentric and alienated. This divisive behaviour attracted further criticism from our soul because it expected us to behave cooperatively or integratively. But we can now see that our divisive, ‘corrupt’, ‘evil’, ‘unsound’, upset state was unavoidable. Our soul’s unjust criticism caused our so-called ‘fall from grace’.

Oh wearisome Condition of Humanity!

Borne under one Law, to another bound:

Vainely begot, and yet forbidden vanity,

Created sicke, commanded to be sound:Page 39 of

Print Edition

What meaneth Nature by these diverse Lawes?

Passion and Reason, selfe-division cause:

Fulke Greville, from his play Mustapha, c 1594—96.

Explanation of our fundamental goodness brings with it the possibility of our return to the ideal state. Our upset can subside now that we know we are good and not bad. Our soul’s criticism no longer upsets us. We are secure now. We can return to the non-upset ideal state we’ve longed for, be it called Heaven, Paradise, Eden, Nirvana or Utopia. The difference is we’ll arrive in a knowing state. We will be like God knowing.

Originally, we were instinctive participants in the ideals. Now we will participate in them consciously and be like gods, knowing, non-upset managers of the world.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets, from Part 5 of Little Gidding, 1942.

Humanity’s journey has been astonishing. The greatest story ever told is our own.

We no longer need to block out our instinct’s criticism of our intellect. For example we no longer need to avoid criticism by emphasising divisiveness in other animals. We no longer need to evade the significance of integration. Now we can acknowledge that evasion of integrative or cooperative ideals has happened on an overwhelming scale. The happy irony is that it has all been for the ultimate strengthening of those ideals.

Humanity has had to cope this far by being evasive but now this evasion can end and many hidden truths can be revealed.

I will utter things hidden since the creation of the [upset] world.

The Bible, Matt. 13:35.