Beyond The Human Condition

Africa — our soul’s home — the Garden of Eden.

Page 55 of

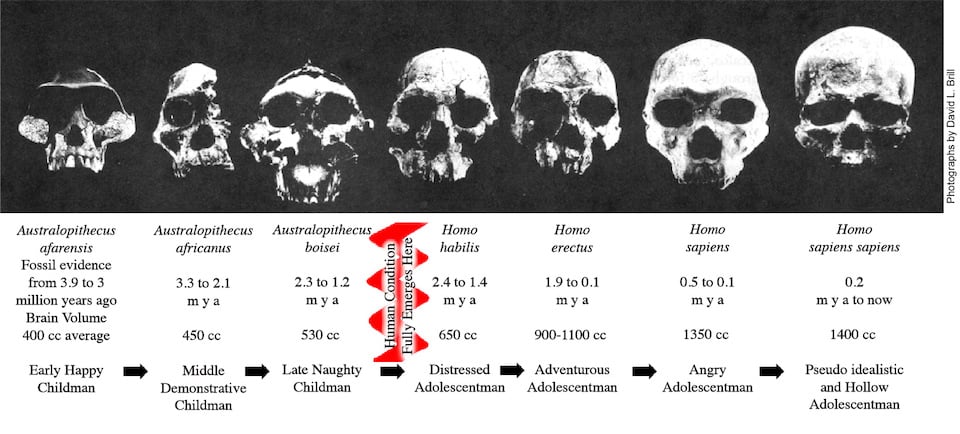

Print Edition 3. The Story of Homo

A question arising from the story of Adam Stork was ‘what was humanity’s instinctive orientation?’ To suggest an answer the picture of the gorillas was shown. Another question to arise is ‘when did the battle between our instinct and our intellect begin?’ To answer this consider the fossilised skulls of our ape ancestor Infantman’s successors, Childman and Adolescentman. This sequence appeared in The Search for Early Man in National Geographic, November, 1985. The psychological stages of childhood and adolescence beneath the skulls (my additions) are explained more fully later. For now, suffice to say that, as with the same stages in an individual human, in infancy we became conscious, in childhood we played with the power of free will that consciousness brought and in adolescence we discovered the responsibility of free will and sought the meaning of life so that we might comply with it. When we began the search for meaning the battle with our instinct broke out.

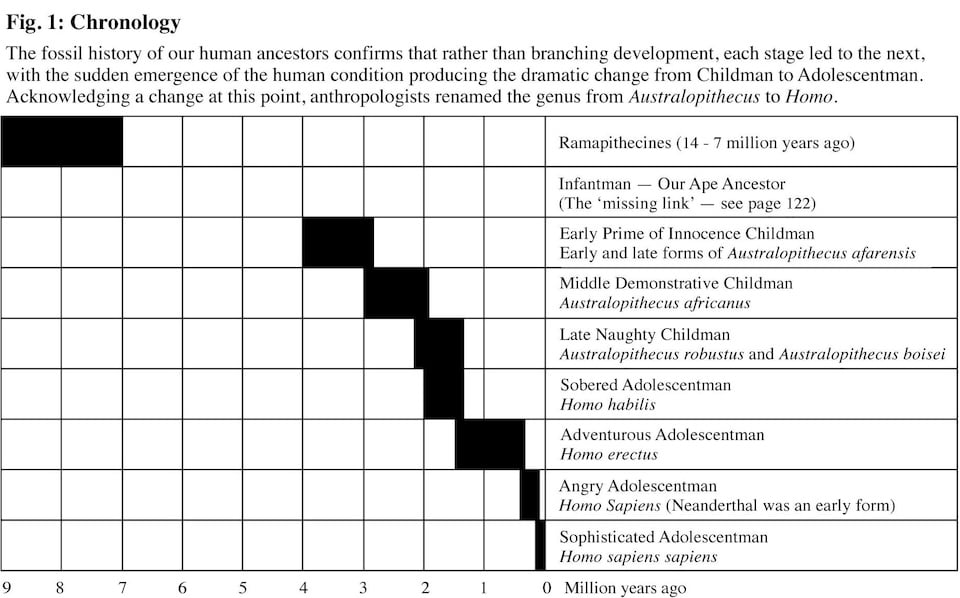

(Traditionally anthropologists have postulated various divergent or branching development in early man, but now we can see that there was no branching — that one stage led to the next. There was only one major development going on, that of the mind. We, unable to look at our psychological development, attributed all significance to everything but Page 56 of

Print Edition that. The prime mover or main influence in human development was surely not meat eating, tool use, language development or walking upright but what was happening in our minds.)

The chronological sequence of these fossils shows that large-domed skulls appeared 2 million years ago in the genus anthropologists call Homo.

Brain volume is probably no longer relevant to intelligence because brain efficiency has no doubt increased, but we may assume that the original emergence of large-domed skulls was to accommodate bigger, more intelligent brains. For example, the developed temporal lobes for remembering and parietal lobes for integrating information from the senses first became clearly evident in the imprint left on the Page 57 of

Print Edition walls of the brain cases of fossilised Homo skulls. As memory and information association form the basis of consciousness, this suggests that Adolescentman Homo emerged some 2 million years ago.

Chart by Jeremy Griffith © Fedmex Pty Ltd 1983

Let’s visualise what happened when consciousness, with its ability to understand, emerged. If our instinctive orientation was towards being integrative or loving, what happened when we had to understand love? What happened when our idealistic instinct met the intellect?

To see what happened we can use another analogy, similar to the stork story, but this time featuring humans.

On the ‘day’ of first contact between instinct and intellectPage 58 of

Print Edition (which in reality happened over many thousands of years), imagine a band of Australos, members of the australopithecines, wandering through the forest and coming upon an apple tree bearing fruit. All the members of this band are still obedient to and dependent on their instincts for management of their lives.

Non-rational creatures do not look before or after, but live in the animal eternity of a perpetual present; instinct is their animal grace and constant inspiration; and they are never tempted to live otherwise than in accord with their own . . . immanent law.

Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy, 1946.

All that is, except one, whom we’ll call Adam Homo. The first fully conscious, intelligent human, he has become sufficiently mentally developed to be able to reason effectively — sufficiently conscious (of how events that occur through time are related) to attempt to think for himself how to behave. For the first time he decides to attempt self-management of his life.

Being an understanding device, his conscious mind requires understanding. But there’s none available to help him make decisions. Feeling hungry and having to make a start somewhere on this process of thinking for himself, Adam Homo looks at the fruit and decides, ‘why not take all the apples and eat them?’

The rest of the tribe remain obedient to their instinctive training in cooperative or integrative selflessness. They are innocent, unaware or ignorant of the world associated with a search for understanding. Consequently, when Adam Homo takes the apples, they criticise him for not sharing them. (Mothers still witness this grand mistake of pure selfishness made by children when they first attempt to self-manage their lives.) Abused by the innocents and his conscience Adam Homo gets a nasty shock. He quickly puts the fruitPage 59 of

Print Edition down, determined to make no more attempts to self-manage his life.

But he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later, he has to defy the criticism and shoulder the responsibility of learning to master his intellect.

To stop the criticism, Adam Homo needs to know and explain to the innocents that, while his intellect needs to be guided by conscience, he doesn’t deserve its criticism. He needs to explain that he’s not bad, that he’s using his conscious mind which is a different learning tool from the one that gave them their perfect instinctive orientation to integration.

His mind requires understanding. He has to search for correct understandings by experimenting with different understandings. Any mistakes aren’t bad, they’re a necessary part of the learning process. But to come up with this explanation, Adam Homo needs 2 million years of investigation. He needs to discover the difference between the gene-based learning system and the nerve-based learning system. He’ll need to learn about the DNA molecule and nerves and many other mechanisms of our world before he can free himself from criticism.

We’ve lived with unfair criticism — on a daily basis and through millennia — and it’s upset us. This upset expressed itself as anger, egocentricity, alienation and superficiality.

When the innocents criticised him, Adam Homo’s first move was to try to defend his actions. He tried to explain that he didn’t deserve criticism, that he wasn’t bad. So he said, ‘The fruit just happened to fall into my lap’.

This apparently blatant misrepresentation wasn’t a lie. It was an inadequate attempt at explanation. Lacking the real excuse or explanation, it was at least an excuse. It was a contrived defence for his mistake. He was evading the false implication that his behaviour was bad. A ‘lie’ that said he wasn’t bad was less a ‘lie’ than a partial truth that said he was!

Page 60 of

Print Edition The contrived excuses for our divisive behaviour have been Social Darwinism (the need to compete for survival), B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning theory (that man is a slave to reward and punishment), Konrad Lorenz’s theory, which excuses our divisive behaviour by saying it is stereotyped and the product of past experiences (i.e. it’s instinctive), Robert Ardrey’s theory, which said our competitiveness was due to an imperative to defend our territory and Edward Wilson’s sociobiology theory, which argues that our selfishness is due to our need to perpetuate our genes.

The latest contrivance is the emphasis given to chaos rather than order in the label ‘Chaos’ Theory. As Stephen Jay Gould (Professor of Geology and Zoology at Harvard University) said, Chaos is fundamentally a deterministic theory (from a lecture in Sydney for the Australian Museum Society, June 15, 1991).

I would point out that each of these contrived excuses contains an element of truth. In fact they represent significant advances in knowledge, but the insight they contain is being presented in such a way as to protect humans from unjust criticism.

The dictionary defines ‘ego’ as ‘conscious thinking self’, so ego is another word for the intellect. Trying to find proof of his worthiness, Adam’s ego becomes increasingly embattled. It becomes focused or centred on trying to establish his worthiness. He becomes egocentric.

Having to attempt to explain himself also meant Adam Homo had to develop language. The Australos had nothing to explain. They were instinctively coordinated and controlled. Beyond contact calls they had no need for language.

Anthropological evidence supports the belief that language emerged with Homo. Study of brain cases in fossil skulls for the imprint of Broca’s area (the word-organising centre of the brain) suggests, according to Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin in their book Origins (1977), that Homo had a greater need than the australopithecines for a rudimentary language.

Page 61 of

Print Edition When Adam Homo found he couldn’t explain himself satisfactorily, he became frustrated and tried to demonstrate that he wasn’t ‘bad’ or ‘inferior’ or ‘worthless’. He picked up a stick and hurled it away, challenging the innocents to throw one as far. When this sad and desperate effort to demonstrate his worth failed to impress, he retaliated against the unfair criticism. He attacked innocence. He struck one of the innocents in a frustrated attempt to stop the unwarranted criticism. Violence, and in the extreme, war, began.

Our ape ancestor, Infantman, would have occasionally hunted animals to eat, as apes are known to do. Such hunting by apes was graphically illustrated in Sir David Attenborough’s 1990 documentary The Trials of Life with scenes of common chimpanzees hunting down and eating colobus monkeys.

While Infantman would have occasionally opportunistically hunted animals for food, Childman Australopithecus would have been exclusively vegetarian. The trend towards integrative friendliness, even towards other animal species, is clearly evident in the step from common chimpanzees to pygmy chimpanzees (see quotes on chimpanzee behaviour on pages 111 to 120). Unlike common chimpanzees pygmy chimpanzees have developed an instinctive appreciation of love. They have developed conscience. Other evidence, such as reduced canines and the wear pattern on the teeth of Australopithecus, indicates that they were vegetarian.

While Childman Australopithecus would have been exclusively vegetarian, hunting appears again in the life of Adolescentman Homo. However, unlike Infantman, who hunted because of the opportunity it offered of acquiring food, Adolescentman ‘hunted’ (actually attacked) animals because he was upset by their innocence. This will now be explained.

Contrary to accepted opinion, hunting in the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of Adolescentman Homo was not for food. In fact research shows that 80 per cent of the food of existing hunter-gatherers, such as the Bushmen of the Kalahari, is supplied by women’s gathering. If providing food were not the reason, why were men so preoccupied, as they were, with hunting?

Page 62 of

Print Edition Hunting was upset Adolescentman’s earliest ego outlet. Men, who have been more egotistical than women (see page 138) attacked animals because animals’ innocence (albeit unwittingly) unfairly criticised them. By attacking, killing and dominating animals men were demonstrating their power in a perverse assertion of their worth. If they couldn’t rebut the accusation that they were bad at least they could find some relief from the sense of guilt engendered by demonstrating their superiority over their accusers. The exhibition of power was a substitute for explanation. This ‘sport’ — attacking animals, which were once our closest friends — was the first great expression of our upset. Anthropological evidence suggests that large-scale big game hunting began during the time of Homo habilis and became well established early in the reign of Homo erectus. With it came meat eating, which would have revolted our instinctive self or soul since it involved eating our soul’s friends. But our spirit (or will to champion our intellect or ego) wasn’t to be put off and in time, as we developed our increasingly upset and driven (to find ego relief) lifestyle we became somewhat physically dependent on the high energy value of meat.

The ‘hunting for food’ explanation is the evasive contrived excuse insecure Adolescentman used for his attack on innocent animals.

As with the !Kung [Bushmen] and other contemporary hunter-gatherers, there was almost certainly more excitement about the men’s contribution than the women’s, even though the plant foods essentially kept everyone alive. There is a mystique about hunting: men pit their wits and skill against another animal, producing the silent tension of stalking, the burst of energy and adrenalin of the chase, and the elation of success at the kill. The challenge of a hunt is overt and visually impressive, the more so the bigger and fiercer the prey.

Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin, Origins, 1977.

Finally, Adam Homo tried to escape the unfair criticism. He ‘put his fingers in his ears’ to block it out and ‘ran away to hide from it’.Page 63 of

Print Edition

‘Early vegetarians returning from the kill’

(There is not the same ego satisfaction in

overwhelming a carrot. — J.G.)

Page 64 of

Print Edition Anthropological evidence shows that our first ‘migrations’ — self-distracting, escapist wanderings — from our ancestral Africa occurred about 1.25 million years ago. For example, the only fossils of pre-Homo erectus humanity have been found in the great Rift Valley of Africa. Revealingly, Africa, where humanity was nurtured and spent its innocent youth, is often called ‘the cradle of mankind’.

So when humanity went in search of meaning or understanding we became:

-

egotistical (forever trying to explain, prove or demonstrate our underlying ‘goodness’ and thereby maintaining our self-esteem),

-

competitive (against the implication that we are bad),

-

aggressive,

-

mentally ‘blocked out’ or evasive and thus alienated (paradoxically, we became especially evasive of the selfless ideal, the integrative meaning of life, because it unfairly criticised our selfish, divisive and apparently disintegrative behaviour),

-

escapist (superficial), and

-

very unhappy.

In short, we became upset.

Since Adam Homo’s aggression, competitiveness and preoccupation with self or selfishness were divisive behaviours, they attracted further criticism from his cooperative or integration-demanding conscience. This greatly compounded his war with his instinct and the other Australos. He now needed even more courage and determination to find understanding. Only understanding could free him from criticism. Suddenly there’s a desperate need for intelligence to find this understanding.

Anthropologists recognise a dramatic increase in the volume of the human brain beginning 2 million years ago.

Page 65 of

Print Edition Upset intensified quickly. In 2 million years of it we’ve come a long way from our original innocent state and have almost totally forgotten true happiness. Nevertheless we were once utterly integrative or loving. Our instinctive heritage is one of behaving lovingly towards others and being treated lovingly.

So our forebears were gentle, loving and cooperative, not aggressive, bloodthirsty brutes as has evasively been propounded by such anthropological commentators as Raymond Dart, Konrad Lorenz, Desmond Morris and Robert Ardrey.

From the objective, scientific viewpoint Richard Leakey, who studied and lived amongst the evidence of early man — in fact he and his parents discovered a lot of it — has this to say about the aggression thesis:

We emphatically reject this conventional wisdom [that war and violence are in our genes] . . . the clues that do impinge on the basic elements of human nature argue much more persuasively that we are a cooperative rather than an aggressive animal.

With the growth of agriculture and of materially-based societies, warfare has increased steadily in both ferocity and duration . . . We should not look to our genes for the seeds of war . . .

Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin, Origins, 1977, both quotes from Chapter 9.

Those who believe that man is innately aggressive are providing a convenient excuse for violence and organized warfare.

Richard Leakey, The Making of Mankind, 1981.

If the anthropological evidence indicates we weren’t aggressive, what might the evidence from the study of primates tell us? Later chapters explain that this evidence too indicates we were not aggressive.

From the subjective, introspective viewpoint our inner awareness of an idealistic, innocent, loving, cooperative past is overwhelming. There is our very deeply ingrainedPage 66 of

Print Edition cooperative-behaviour-insisting conscience itself, the idealism of our youth and our expectation to be loved. Where did these instincts come from? A brutish, savage, wild, aggressive, divisive past? Impossible! We even have an instinctive memory that crops up in all mythologies of a time when we were innocent of upset. The fact is our soul, with its undeniable expectations of love, exists in us. No one complains when they are loved! As well, we all know innocence accompanies youth. Anger, egocentricity and alienation came with age. Humanity started out innocent.

Every mythology remembers the innocence of the first state: Adam in the Garden, the peaceful Hyperboreans, the Uttarakurus or ‘the Men of Perfect Virtue’ of the Taoists. Pessimists often interpret the story of the Golden Age as a tendency to turn our backs on the ills of the present, and sigh for the happiness of youth. But nothing in Hesiod’s text exceeds the bounds of probability.

The real or half-real tribes which hover on the fringe of ancient geographies — Atavantes, Fenni, Parrossits or the dancing Spermatophagi — have their modern equivalents in the Bushman, the Shoshonean, the Eskimo and the Aboriginal.

Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines, 1987.

This shrill, brittle, self-important life of today is by comparison a graveyard where the living are dead and the dead are alive and talking in the still, small, clear voice of a love and trust in life that we have for the moment lost. . . . [there was a time when] . . . All on earth and in the universe were still members and family of the early race seeking comfort and warmth through the long, cold night before the dawning of individual consciousness in a togetherness which still gnaws like an unappeasable homesickness at the base of the human heart.

Laurens van der Post and Jane Taylor, Testament to the Bushmen, 1984.

Having battled ignorance for 2 million years humans have now almost spent their innocence. Innocence in human lifePage 67 of

Print Edition is now normally extremely brief. We have been immensely heroic in our search for understanding but it has left us extremely upset and exhausted in soul.

They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.

Samuel Beckett from his play Waiting for Godot, 1955.

‘Dear little swallow’, said the Prince. ‘You tell me of marvellous things. But more marvellous than anything is the suffering of men and women. There is no mystery so great as misery. Fly over my city, little swallow, and tell me what you see there’.

Oscar Wilde, The Happy Prince, 1888.

From Adam Homo’s first unknowing mistake developed what the innocents and his instinctive self saw as deliberate mistakes. They saw his upset as proof of his badness. As far as they were concerned, he had become ‘evil’ or ‘sinful’.

It was the instinctive self’s ignorance of the conscious mind’s need to search for understanding that led to this intolerable situation. Adam Homo was forced to live with a sense of guilt that was completely unjustified and unwarranted.

The human condition is our predicament of having to live with a sense of guilt. Understanding dissolves the guilt: the origin of all human upset was our instinctive self’s unjust criticism of our conscious mind’s necessary efforts to find understanding.