The Great Exodus

Page 161 of

PDF Version 38. Adventurous Early Adulthood Stage of Adolescent Humanity

This is our Adventurous Adolescentman stage, the time when we take up the battle to overthrow ignorance of our idealistic instinctive self or soul as to the fact of our fundamental goodness.

The species: Homo erectus—1.5 to 0.5 million years ago

The individual: 21 to 30 year old

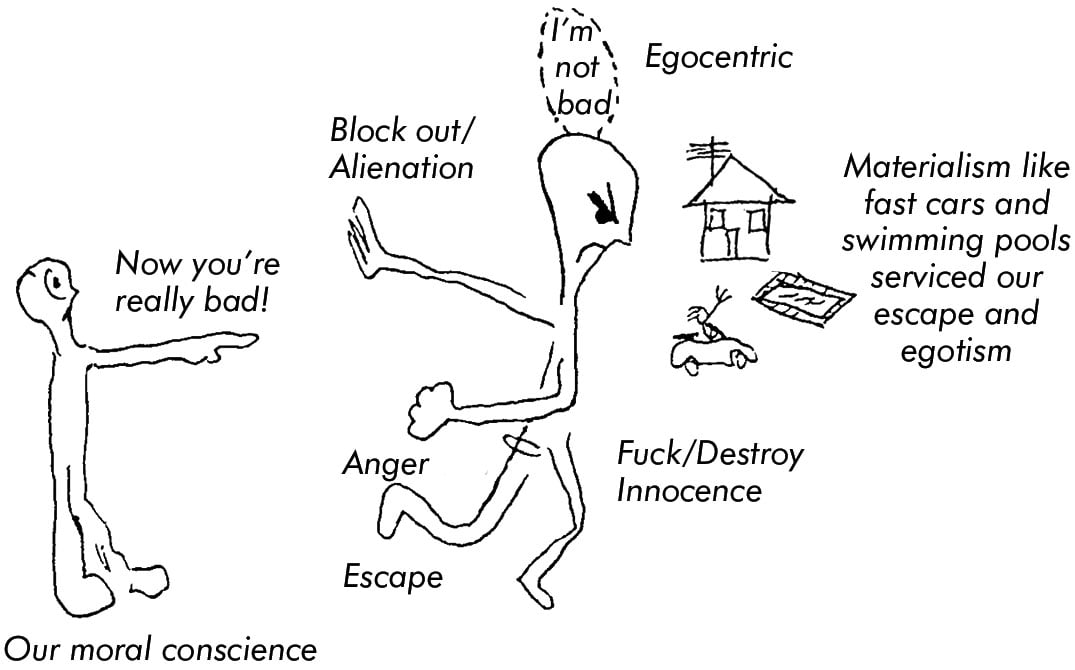

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © 1991-2011 Fedmex Pty Ltd

By 21 years of age, after six years of blocking out the negatives and focussing only on the tiny positives available to it, resigned humans finally adjusted to life in resignation. In the case of those who hadn’t resigned, by 21 years of age they had followed a similar path in that they had to adjust to the prospects of a life of ever-increasing upset in themselves and in humanity as a whole. Basically they realised there was no point dwelling on their and the world’s plight and that they could do no more about those situations other than get on with their life and hope to make some improvement to the overall situation the world was in along the way. Thus by 21 years of age both resigned and unresigned young adults had been able to arm themselves sufficiently well with a positive attitude to commit themselves to the battle that humanity as a whole was involved in of gradually, step by step, generation by generation working themselves towards one day accumulating sufficient knowledge to be able to explain the human condition and by so doing liberate humanity from the undeserved guilt that was so upsetting humans. In fact by 21 young adults had made sufficient adjustments to be raring to go. Twenty-one year old men in particular had become so focussed in their minds on the positive of the adventure of attempting to make a good fight of the battle to defeat our soul’s ignorance as to the fact of the true goodness of humans and to resist for as long as possible becoming completely corrupted in themselves, that they were cavalier and swashbuckling. Naive about just how quickly overwhelming the battle was going to become they had plenty of strength and resilience—plenty of ‘rock-n-roll’. For their part 21 year old women had also become firmly focussed on the few positives they had of the reinforcements they could receive from men for their physical beauty and of the satisfaction of being able to support men and nurture another generation of brave humans to carry on humanity’s heroic struggle. It has been a long-held tradition in western societies to hold a so-called ‘coming of age’ party for Page 162 of

PDF Version offspring when they turned 21. The 21 year old was traditionally given a key symbolising that they were at last ready to leave home and ‘face the world’. Thus, with a big kiss from Mum and a slap on the back from Dad the young adult left home ‘to see what life held for them’. Interestingly, the fact that they were considered sufficiently adapted to life under the duress under the human condition to become independent at 21 rather than at the round figure of 20 is an indication of just how precisely all these stages with ages that are being described really were.

Basically the 20s, during humanity’s adolescence, was the period during which we began refining all the techniques needed to cope with living with the horror of the human condition. During our teenage years we agonisingly adjusted to having to accept a life of living with upset and during our 20s we took up the challenge of living out that life. Our forebears who lived in humanity’s adventurous early adulthood stage throughout their lives was Adventurous Adolescentman, H. erectus. They lived from 1.5 million years ago to 0.5 million years ago. Consistent with the description that has been given for this stage, fossil evidence has revealed that it was H. erectus who adventured out from our ancestral home in Africa around 1.25 million years ago and migrated throughout the world.

As mentioned it was during the 1 million year reign of Adventurous Adolescentman that humanity perfected the many techniques for coping with the human condition, techniques that have been part of human life for so long now we tend to think of them as having always been part of our species’ make-up. We describe them now as simply ‘human nature’. In truth an immense transition took place in our nature—what we became was nothing at all like what we were. To clearly see the phenomenal transition we need to recall that we changed from living a totally integrated cooperative, loving existence to living in an immensely upset angry, egocentric and alienated state. In his poem Theogony, Hesiod gave a good description of the integrated existence: ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind / Nor e’er decrepit age misshaped their frame…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…Dying they sank in sleep, nor seemed to die / Theirs was each good; the life-sustaining soil / Yielded its copious fruits, unbribed by toil / They with abundant goods ‘midst quiet lands / All willing shared the gathering of their hands.’ By contrast, we became beings suffering from upset which the so-called seven deadly sins provide a useful description of, namely lust, anger, pride, envy, covetousness, gluttony and sloth. These upsets are really only another way of describing the specific upsets that came with the human condition of anger, egocentricity and alienation, as the following analysis makes clear.

In the case of anger, hunting down and killing animals was the first great expression of our upset anger and egocentricity. It has always been said that the hunting in the ‘hunter-gatherer’ lifestyle that characterised virtually all of the 2 million year period of humanity’s adolescence was primarily for food. This evasive belief has so far protected us from the condemning truth of the extreme aggression involved in hunting. In fact, research shows that 80 per cent of the food of existing hunter-gatherers, such as the Bushmen of the Kalahari, is supplied by the women’s gathering (Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers, eds. Richard B. Lee & Irven DeVore, 1976, p.115 of 408). If providing food were not the reason, why then were the men hunting? Hunting was men’s earliest ego outlet. Men attacked animals because their innocence, albeit unwittingly, unfairly criticised them. Also, by attacking, killing and dominating animals men were demonstrating their power, which was a perverse way of demonstrating their worth. If men could not rebut the accusation that they were bad at least they could find some relief from the guilt engendered by demonstrating their superiority over their accusers. The exhibition of power was a substitute for explanation. Page 163 of

PDF Version This ‘sport’ of attacking animals, which were once our closest friends, was, as mentioned, one of the earliest expressions of our upset. One of the definitions given for ‘sport’ in the Encylopedic World Dictionary is ‘the pastime of hunting, shooting, or fishing with reference to the pleasure achieved: “we had good sport today”’ (1971). The ‘pleasure’ of hunting was the perverse one of attacking animals for their innocence’s implied criticism of us. Anthropological evidence supports the notion that hunting is an aspect of fully conscious, upset Adolescentman because evidence of hunting first appears during this time. All the anthropological evidence indicates Childman was a vegetarian. With big game hunting came meat eating, which would have revolted our original instinctive self or soul since it involved eating our soul’s friends—in fact even today killing animals causes a reaction of deep revulsion within us. But we weren’t to be put off and in time, as we developed our increasingly upset and driven (to find ego relief) lifestyle, we became somewhat physically dependent on the high energy value of meat. Nevertheless, although using meat for food could justify the effort of hunting, the hunting was fundamentally about attacking innocence. It should be pointed out that the destruction of innocence, such as the destruction of animals has been going on at all levels. As will be explained next, men attacked and destroyed the innocence of women through sex. Humans also destroyed the innocent soul in themselves by repressing it. All forms of innocence unfairly criticised humans, so all forms of innocence were attacked by us. We not only attacked animals, we attacked nature in general because all of nature was a friend of our soul and not a friend of our apparently ‘bad’ mind. Chopping down a tree or setting fire to vegetation were often acts of aggression perpetrated upon nature for its implied criticism of us. The wearing of dark glasses ostensibly as sunshades was often an effort to alienate ourselves from the natural world that was alienating us—was an attack on the innocence of the daytime.

Attacking and killing and murdering each other and eventually outright warfare represented a dramatic escalation in our upset with the condemning innocence of the ideal world of our soul. As will be explained during the 40 year old stage, this extremely destructive behaviour didn’t emerge until the latter period of our 2 million years in adolescence.

Having turned on and attacked our innocent animal friends men next turned on the relative innocence of their partners in life, women, and attacked that. As was explained in Section 22, we can now understand that lust is also part of our upset anger. Men perverted the act of procreation, they invented sex as in ‘fucking’ or destroying or sullying the relative innocence of women. Prior to the perversion of ‘sex’ women weren’t viewed as sex objects and therefore nudity had none of the problems of attracting lust and there was no need to conceal our nakedness with clothes. To quote the Bible, when Adam and Eve took the fruit from the tree of knowledge—set out in search of understanding—‘the eyes of both of them were opened, and they realized that they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves’ (Gen. 3:7). Clothing was not originally to protect the body from cold as children have been evasively taught at school but to restrain lust. While the Bushmen of the Kalahari, who are a relatively innocent race and still living naturally as hunter-gatherers do, go about almost naked they do wear covering over their genitals. Once we became extremely upset even the sight of a women’s ankle or face became dangerously exciting to men, which is why in some societies women are completely draped. For example, in Islamic communities a veil is worn not out of respect for women, as is often evasively claimed, but out of disrespect for them. By repressing sex and sexual attraction, such as the custom of purdah for women in Islamic societies, the spread of sexual destruction could be restricted. The convention of marriage was invented as one way of containing this spread of upset. By confining sex to a life-long relationship, the Page 164 of

PDF Version souls of the couple could gradually make contact and be together in spite of the sexual destruction involved in their relationship. As stated in the Bible, in marriage ‘a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh. So they are no longer two, but one’ (Mark 10:7,8.). Brief relationships kept souls repressed and spread soul repression. It needs to be explained that the more upset, corrupted, insecure and alienated humans became the more they needed sexual distraction and reinforcement through sexual conquest (in the case of men) and sex-object attention (in the case of women), and thus the more difficult it became for them to be content in humans’ original monogamous relationships. The saying ‘the first cut is the deepest’ is an acknowledgment of the deep and total commitment humans make to their first love. It reveals that the original, relatively innocent relationship between a man and a woman was a monogamous relationship. Since sex killed innocence, ideally—although this was impractical for the majority of the human race who had to ensure the continuation of the species—if we wanted to free our soul from the hurt sex caused it we needed to be celibate. As Christ explained it, some priests ‘renounce marriage [for] the kingdom of heaven’ (Matt 19:12). Sex killed innocence, it was an act of aggression—but, as was explained in Section 22, on a nobler level it was also an act of love. While sex was an attack on innocence it was also one of the greatest distractions and releases of frustration and, on a higher level, an expression of sympathy, compassion and support—an act of love. As was explained earlier, the emotions involved in sexual relationships were also part of romance, part of the dream that the image of innocence could inspire of living ideally, free of the human condition. The lyrics of the song Somewhere, written by Stephen Sondheim for the blockbuster 1956 musical (and later film) West Side Story, perfectly describe the dream of the heavenly state of true togetherness that humans allow themselves to be transported to when they fall in love: ‘Somewhere / We’ll find a new way of living / We’ll find a way of forgiving / Somewhere // There’s a place for us / A time and place for us / Hold my hand and we’re halfway there / Hold my hand and I’ll take you there / Somehow / Some day / Somewhere!’ The 1928 song Let’s Fall In Love, written by Cole Porter, also has lyrics that reveal how falling in love is about allowing yourself to dream of the ideal state, of ‘paradise’: ‘Let’s fall in love / Why shouldn’t we fall in love? / Our hearts are made of it / Let’s take a chance / Why be afraid of it / Let’s close our eyes and make our own paradise’. The escape from the horror of a resigned world oppressed and upset by the human condition that falling in love is concerned with achieving is expressed in these lyrics from the 1977 Fleetwood Mac song Sara: ‘Drowning in the sea of love / Where everyone would love to drown’.

The effect of the ‘attraction’ of innocence for both dreaming through and for sexual destruction was that our physical features became increasingly neotenous throughout the 2 million year journey through our species’ adolescence, as the increasingly child-like features of the skulls of the varieties of our Homo ancestors evidence. The dramatic increase in neoteny from H. habilis to H. erectus reflects the dramatic increase in upset that took place once humanity set out on its search of understanding at the age-equivalent of 21, and the dramatic increase in neoteny from H. erectus to H. sapiens sapiens reflects the dramatic increase in upset that occurred when humanity entered the rapidly dis-integrating stage in the development of upset in the last quarter of the exponential growth of upset’s development. Throughout humanity’s infancy and childhood neotenous, childlike features of a domed forehead, large eyes, snub nose and hairless body were selected for because during the love-indoctrination process youthfulness was associated with integrativeness because the older the individual the more the training in love wore off. Throughout humanity’s adolescence this integrative purity continued to be sought after but for an entirely different reason, this time it was desired because of its power to inspire Page 165 of

PDF Version the dream of freedom from the human condition and because of its ‘attractiveness’ for sexual destruction. In fact the only form of innocence to be cultivated instead of destroyed throughout humanity’s adolescence was the image of innocence, especially in women. The extent that women have been exposed and therefore adapted to sexual destruction is evident in their more neotenous facial features and significantly less body hair. Just how adapted women have become to being sex objects is that women’s magazines are almost entirely dedicated to showing women how to be ‘attractive’, which means better able to imitate the image of innocence. Women are now codependent and habituated to the reinforcement that men over 2 million years have given their object self rather than their real self. They love to adorn themselves with beautiful objects, use make-up on their faces to increase their neotenous appearance and wear high-heel shoes to give themselves the leggy, youthful, almost pubescently ultra-innocent look.

It might be mentioned here that, along with neoteny, the increased brain volume in the skulls of our ancestors—as an indicator of increased intelligence— also evidences the psychological journey being described in this section. The whole development of upset was driven by increasing intelligence. The more intelligent we were the more we searched for understanding and the more upset we became and with each new level of upset a new psychological and accompanying physical existence and state emerged. While the brain size of Childman (the australopithecines) was not much bigger than Infantman (such as chimpanzees and bonobos), there is a sudden increase in brain size in the first Adolescentman, H. habilis. As depicted in the chart of the development of mental cleverness at the beginning of this section, this dramatic growth continued through Adventurous Adolescentman (H. erectus) and Angry Adolescentman (H. sapiens) before finally plateauing with Pseudo Idealistic Adolescentman (H. sapiens sapiens). Anthropologists have long wondered why this growth stopped. The reason is that in Pseudo Idealistic Adolescentman a balance was struck between the need for cleverness and the need for soundness. A balance had to be arrived at between answer-finding but corrupting mental cleverness and conscience-obedient but non-answer-finding lack of mental cleverness. The average IQ today is that amount which is relatively safely conscience-subordinate, although, as we will see, upset has finally managed to become excessive despite this restraint. The average IQ today has the right balance of soul and IQ, so by stressing the need for a high IQ, as our education institutions in particular have been doing, was unbalanced. Too much IQ and we diverged too quickly and too far from our soul and all the ideals and truths its knows and as a result became too in need of denial and thus too alienated; too little IQ and we were too conscience-obedient.

Pride and envy are expressions of egocentricity, of excessively needing reinforcement through success, power, fame, fortune, adulation and glory. As upset increased so too did our insecurity about being corrupted, and with it the need to combat that insecurity with whatever reinforcement we could find. As was explained in Section 22, since it was men, who, as the group protectors, had to especially take on the responsibility of championing the conscious-thinking self or ego over the ignorance of our original instinctive self, it was men who came to particularly seek out power, fame, fortune and glory. In the soundtrack of the 1986 African musical Ipi Tombi, the female narrator says, ‘The women had to do all the work because the men were so busy being big, strong and brave’ (Narration: Sesiya Hamba, Drinking Song, Thandi Lephelile). This quote acknowledges just how preoccupied men eventually became trying to prove their worth; defeat the implication that they weren’t worthy. Men became so insecure/ego-embattled that in the end it was a case of ‘give me liberty or give me death’, ‘no retreat, no surrender’, ‘death before dishonour’—they just stood there refusing to do anything except receive glorification and adulation, which meant someone else had to Page 166 of

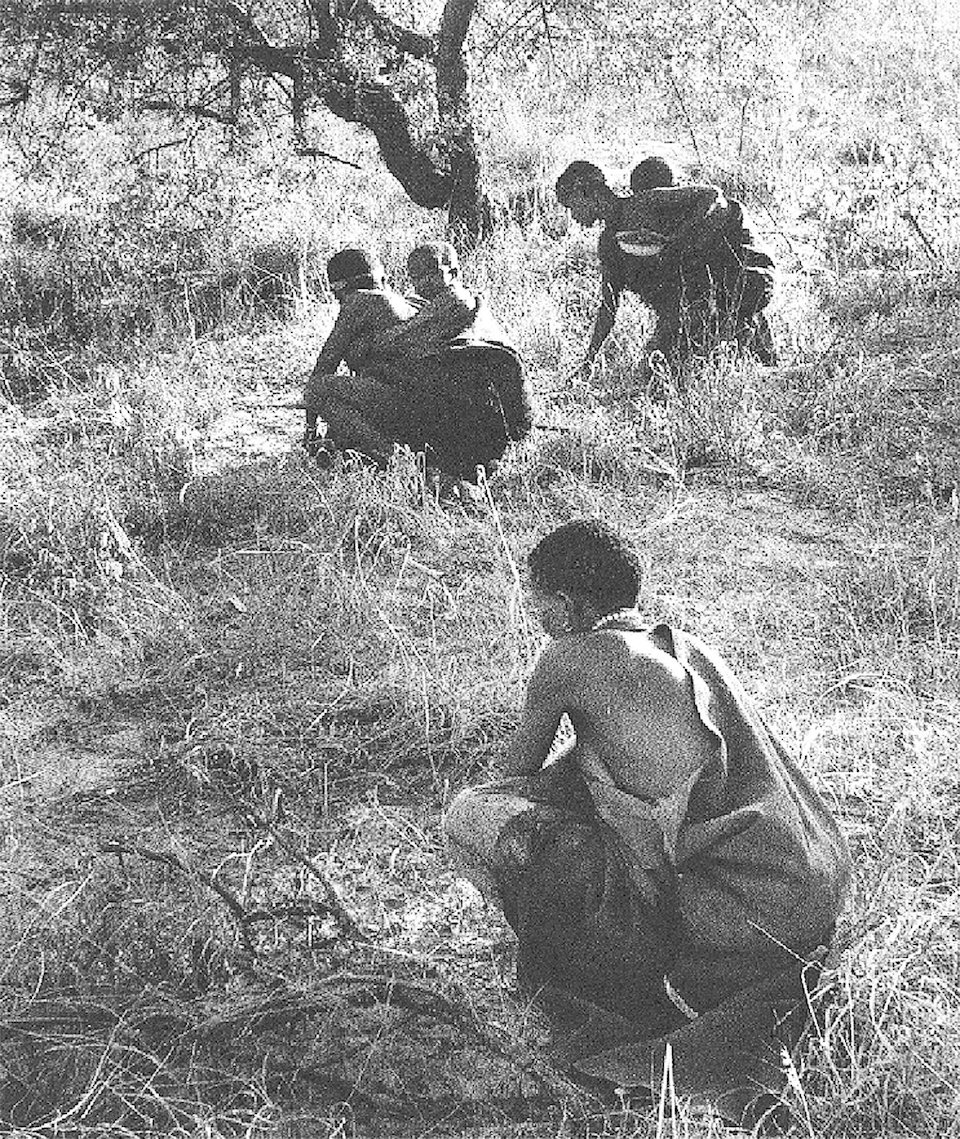

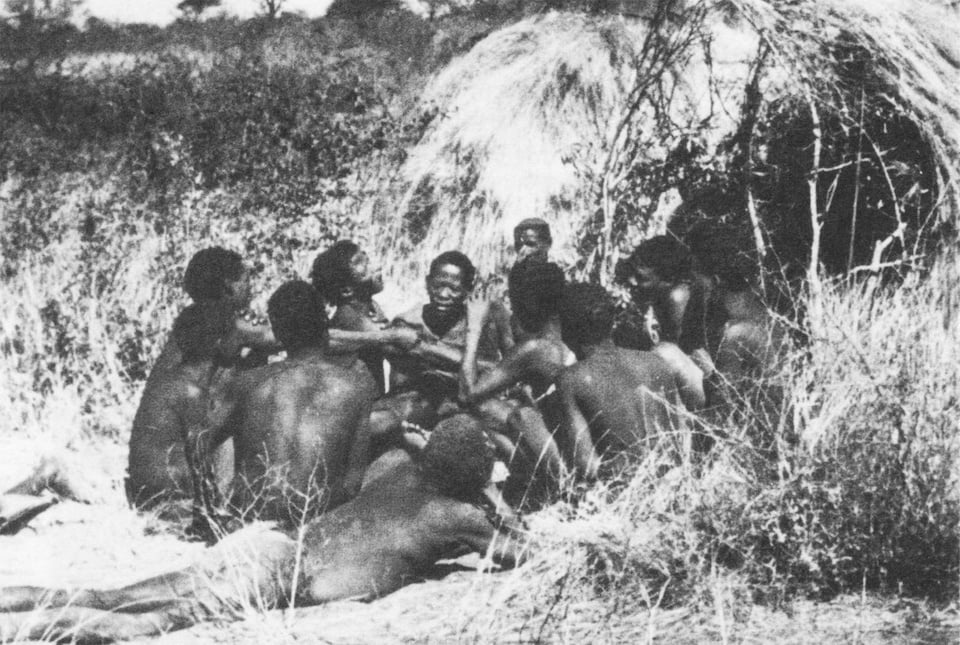

PDF Version do all the work if any was going to get done. The following two pictures of the relatively innocent, but nevertheless members of present 40 year old equivalent H. sapiens sapiens variety of humans, well illustrates the situation. In the first picture women are shown gathering the food, nurturing the children—basically doing all the work—while the other photograph, titled ‘Telling the Hunt’, shows the men sitting around together with their backs despisingly faced towards innocent nature, boldly telling of their heroic conquests over innocent animals.

Photographs by Marjorie Shostak/Anthro

Women with infants digging roots

Photographs by Marjorie Shostak/Anthro

Telling the Hunt

Page 167 of

PDF Version Covetousness, gluttony and sloth refer to the alienation aspect of the human condition. The more upset we became the more we needed ways of escaping and relieving the trauma of our condition. We coveted luxury and comfort; we sought material rewards for the high price we were having to pay of becoming corrupted. Later, when upset became extreme, materialism became one of the main driving forces or motivations for life. Glittering dresses, sparkling champagne, huge chandeliers, silver tea sets, big houses, swimming pools and shining, pretentious limousines gave us the fanfare and glory we knew was due us but the world in its ignorance would not give us. In the end we couldn’t consume enough, be it material goods, food, luxurious holidays, etc—we became gluttons. From being bold, challenging and confrontationalist the heroic 21 year old eventually became embattled and exhausted, much in need of escapism and relief and thus an increasingly superficial and artificial person. We abandoned any idealistic hope of winning the battle to overthrow ignorance as to the fact of our true goodness and became realists, concerned with only finding relief and bestowing glory upon ourselves. We adopted the axiom that ‘to live well is the best revenge’ (against the unjust condemnation of life).

Further, since we were having to live basically dead in intellect and soul there was little to motivate us and we became lazy. Sloth or laziness is lack of enthusiasm which is really alienation; that is, separation from our upset-free, uncorrupted, non-alienated, original innocent, untroubled, happy, ‘child-within’, instinctive self or soul. In fact, ‘enthusiasm’ derives from the Greek word ‘enthios’ which means ‘God within’. Within ourselves is an upset-free, Godlike-in-its-purity, innocent, uncorrupted self that tragically we, our conscious self, had to attack and repress—because it unjustly condemned us. In order to find knowledge, we had to be prepared to oppress our unjustly condemning, innocent, instinctive self or soul. The proverbs, ‘[we had] to hurt the ones we love’ and, ‘[we had] to be cruel to be kind’ sum up the horrible paradox of the human condition. The effects of all this focus on escapism and materialism as a direct alternative to self-confrontation and thinking was that we became extremely shallow, superficial and artificial beings.

As was explained in Section 25, while innocent Childmen were instinctively coordinated and connected, once upset and alienation from each other developed language became a necessity. With alienation differing from one person to another there was a need to try to explain ourselves, try to explain why we were behaving differently. In fact talking became the key vehicle for justifying ourselves in our minds. Since we couldn’t talk directly about the human condition, or about other people’s particular state of alienation without overly confronting and condemning them, stories became a way of passing on knowledge, or what we call wisdom about the subtleties of living under the duress of the human condition. Culture was basically the activity of passing on from one generation to the next the knowledge learnt about living under the duress of the human condition. The culture of Childman was instinctively imprinted in each generation so there was little to have to be passed on during an individual’s lifetime, but with the emergence of upset that situation changed dramatically. Much later, with the development of the written word at about 6,000 years ago, the fundamental quest for self-justification became greatly assisted because the thoughts of one generation’s thinking could be more accurately passed on to the next with the result that suddenly the accumulation of knowledge gained real impetus. Throughout the journey through humanity’s adolescence, the need to explain and justify ourselves with words became increasingly sophisticated with all kinds of excuses and lies being invented. The industry of denial became one of the main features of our behaviour. Page 168 of

PDF Version This book’s documentation of the extreme denials that are taking place in science bears stark witness to just how sophisticated the art of denial has become.

Other forms of self-expression such as art and music became particularly useful because, unlike words, their message wasn’t as clear and therefore as potentially confronting. Each person could derive as much meaning from the art or the music or even the dance and other cultural rituals as they could personally cope with. Even though the oldest known cave paintings are just 35,000 years old, archaeologists working in Zambia announced in 2000 that they had found pigments and paint grinding equipment believed to be between 350,000 and 400,000 years old. At the time of the discovery it was reported that the find showed that ‘Stone Age man’s first forays into art were taking place at the same time as the development of more efficient hunting equipment, including tools that combined both wooden handles and stone implements…[and that it was evidence of] the development of new technology, art and rituals’ (BBC World News, 2 May 2000). British archaeologist Dr Lawrence Barham, a member of the team in Zambia, described the find as the ‘earliest evidence of an aesthetic sense’ and said that ‘It also implies the use of language’ (ibid). The reference here would be to develop language because, as Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin were quoted as saying earlier, the study of brain cases in fossil skulls for the imprint of Broca’s area (the word-organising centre of the brain) suggested that ‘Homo had a greater need than the australopithecines for a rudimentary language’. The oldest musical instruments found so far, phalange whistles, show that Neanderthals, the early variety of H. sapiens sapiens, were making music around 80—100,000 years ago. A Neanderthal burial site at the Shanidar Cave in the Middle East, estimated to be around 50,000 years old, contained traces of pollen grains indicating that bouquets of flowers were buried with the corpses. The creative and aesthetic sense of our ancestors of nearly half a million years ago that the pigments and paint grinding equipment indicate suggests that the creative and spiritual sensitivities demonstrated by the Neanderthals were in existence long before their time.

Throughout humanity’s journey through its adolescence technology was also growing. Its rate of development mirrored the exponential increase in intelligence, with the dramatic improvements only occurring in the very final 14,000 year period of those 2 million years. Sharpened stones, choppers, hand axes and scrapers, cudgels, spears, harpoons and bone needles are found in the archaeological record from 3 million years to 12,000 . H. erectus made refined tear-drop shaped flint axe heads and there is strong evidence of hearths at Koobi Fora in Kenya that indicate even the earliest H. erectus were using fire. It is only after 12,000 that the bow and arrow, fish basket traps and crude boats appear. The practice of agriculture and the domestication of animals began around 9,000 and with it the production of earthenware pottery, looms, hoes, ploughs and reaping-hooks. At around 5,000 the Stone Age was replaced by the so-called Bronze Age which in turn was replaced by the Iron Age around 1,100 .