The Great Exodus

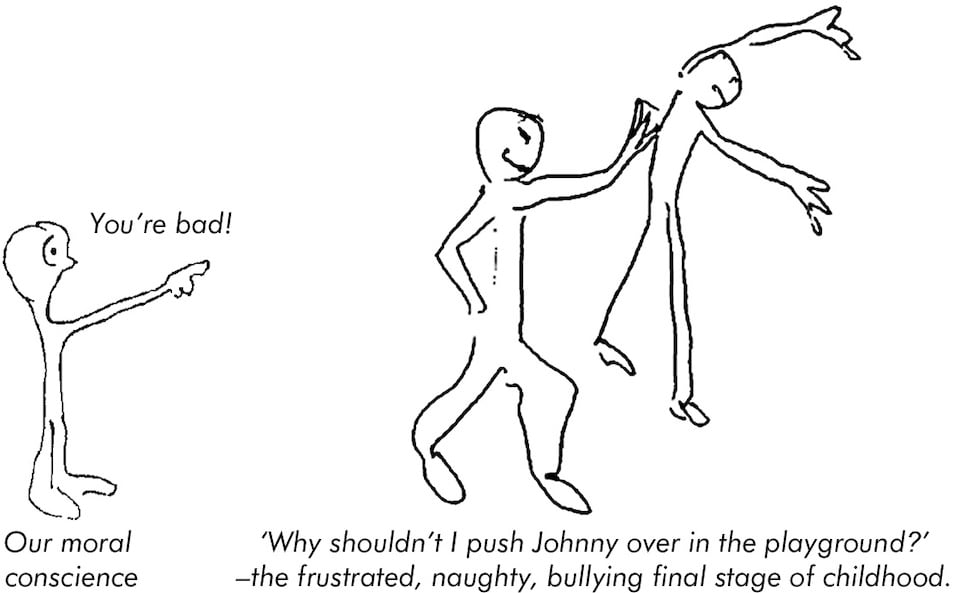

34. Late Naughty Childhood

This is our Late Naughty Childman stage, the time when the intellect naively lashes out at the unjust criticism it is experiencing from its first tentative experiments in self-adjustment.

The species: The robust australopithecines (A. robustus and A. boisei)—2.5 to 1 million years ago

The individual: 9, 10 and 11 years old

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © 1991-2011 Fedmex Pty Ltd

Page 144 of

PDF Version Since school teachers become very aware of the stages children go through, I asked a teacher to describe what she and her colleagues knew of the stages children and early adolescents go through. These are the main points from the response she collected: ‘Six and seven-year-olds are considered to be very compliant but by eight children are starting to test the waters and challenge the world a little.’ She said ‘the eight-year-olds can be annoying and a little naughty’, while ‘nine and ten-year-olds can be hard to handle as they seem to hit a phase of recklessness’ and ‘are considered naughty’. She said ‘Teachers love teaching 11 and 12-year-olds because it is during this stage that children become civilised.’ She commented that ‘Teachers consider years nine and ten, when students are 14, 15 and 16 years old, the most difficult to teach. The adolescents seem to be at complete odds with what is expected of them. Most teachers are terrified of these completely uncooperative mid-teenage ages’ (personal communication, 1997). What has been said here adds weight to the explanations being given of the stages of maturation of consciousness through childhood—and is confirming of the explanations that will shortly be given for the stages in early adolescence.

It was said earlier that the adjustments children have to make growing up in a world that is already upset are, to a large extent, going to be to the influences of that external upset rather than to the effects of the upset from the child’s own experiments in self-management. Clearly the greater the influence of external upset the less significant is the upset from the child’s own experiments in self-management. To see the effects from a child’s own experiments in self-management we would need to find a child who had no encounters with any existing upset in the world and clearly that is not possible. What we have to do is imagine what such a necessarily pristine environment would be like, and with understanding now of the human condition this is not difficult to do.

By eight years of age we can expect that in the pristine situation the child would justifiably feel resentful towards the ‘criticism’ emanating from its instinctive self of its tentative efforts to self-manage its life using understanding. Unable to adequately cope with this ‘criticism’ with understanding of it we can expect the child would begin to retaliate against the criticism as the only form of defence it has available to it. The problem then would be that these early, relatively mild experiments in retaliation of anger, selfishness and dishonest excuse-making in mid-childhood would have the alarming effect of greatly increasing the ‘criticism’ from the child’s integratively orientated instinctive self. From being mildly insecure we can expect the child to now feel guilty and that this drastic escalation in criticism and thus frustration would be a contributing factor to the turbulent, boisterous ‘naughty nines’ that parents and teachers have labelled this stage. By the end of childhood, at the ages of 10 and 11, we can expect the resentment and frustration to be such that it would express itself in the form of taunting and bullying the innocent soul, and, since the world was a friend of the soul—they had ‘grown up together’—by bullying and taunting the world in general. The child would be belligerently lashing out at the unjust world: ‘why shouldn’t I feel resentful and retaliate?’, ‘why shouldn’t I shove you around if I can, especially since I’m more powerful?’ and ‘what’s wrong with being selfish and aggressive anyway?’ Of course even during humanity’s relatively upset-free childhood it wasn’t just the child’s instinctive self or soul that criticised its intellect’s tentative experiments in self-adjustment, parents and the wider society also criticised and tried to orientate the early misadventures, so-called ‘misbehaviours’ of the child’s emerging intellect.

We now have to look at the influence upon the child of having to cope with an already upset world. We can expect that the child is experiencing all the frustrations Page 145 of

PDF Version with, and responses to its own experiments in self-management just described, however, depending on how much external upset it is encountering, that pristine process will also be influenced by the external upset in the child’s world. In the situation that exists today where the external upset is almost overwhelming in its scale and significance we can expect that almost all of the child’s upset will be a result of its encounter with external upset. In fact the influence of the upset that exists in the world today must be overwhelmingly significant for innocent children. Whatever upset is emerging in them from their own experiments in self-management must be insignificant compared to the adjustments the child is having to make to the horrifically upset world that they, in their unguarded innocence, can fully see and feel. The increasingly thoughtful child can see the whole horribly upset world and is totally bewildered and troubled by it. In fact anxiety about the state of the world has to be the main characteristic of late childhood for all children growing up in an already upset world. Eight year olds will only be beginning to be consciously aware of the horror of the state of the world they have been born into but by nine they will have become aware of that horror and be needing a lot of reassurance that everything ‘is going to be alright’. In fact nine year olds can be so troubled by the imperfection of the world that they go through a process of trying not to accept that it is true. They hate that the world is ‘not right’ to the extent that they can put their hands over their ears and eyes and refuse to move and just wait in the hope that the problems will all go away. On page 223 of A Species In Denial there is a short essay by Olive Schreiner in which she describes very clearly this utterly despairing stage when, as she said, ‘all the world seemed wrong to me’. By ten this despair about the state of the world reaches desperation levels with nightmares of distress for children. It is a very unhappy, lonely, needing-of-love time for them. By 11 in this horror world that children now encounter, they enter the ‘Peter Pan’ stage where they decide they don’t want to grow up, they decide they want to stay a child forever with all the things they love and not ever become part of the horror world they have discovered. It is no wonder ‘Teachers love teaching 11 and 12-year-olds’ who have ‘become civilised’, namely quietened right down compared to the ‘reckless’, ‘naughty’ ‘nine and ten-year-olds’.

There is evidence in the fossil record of the description that has been given of these stages of Childman. The early Australopithecus afarensis that have been described as being in the early happy, prime of innocence stage and the subsequent Australopithecus africanus who have been described as being in the middle demonstrative childhood stage are both finely built compared to the much more robustly built Australopithecus boisei and associated Australopithecus robustus that have been described here as Late Naughty Childman. Anthropologists have even placed the more robust late australopithecines on a separate, dead-end branch to Homo but that has to be impossible as there was only one major development going on and that was the psychological one. In biology for there to be branching there has to be deflecting influences such as Darwin’s finches gradually becoming adapted to different food niches on the Galápagos Islands. In a situation where there is only one all-dominant influence causing change there is no opportunity for divergence to develop. From infancy onwards humans have been under the all-dominant influence of what was going on in their heads, namely the development of consciousness and its psychological consequences. Any other influence was so secondary as to be ineffectual in causing branching on the path we were on. While we haven’t been able to explain the human condition we haven’t been able to attempt a psychological analysis of ourselves let alone our ancestors. As an Attorney-General of Massachusetts once said, ‘The Page 146 of

PDF Version art of psychiatry is just one step removed from black magic’ (The Australian, 19 July 1983), and as the title of a 1992 book by James Hillman and Michael Ventura reveals, ‘We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World’s Getting Worse’. Now that we can explain the human condition this hopeless situation changes and we can effectively look at and understand not only our own psychological state but that of our ancestors; we can understand what happened to cause these differences in our ancestors. If the robust australopithecines weren’t a branch then why was there such a big difference between them and the much more gracile or fine featured preceding A. afarensis and A. africanus, and also why was there such a big difference between the robust australopithecines and the variety of early humans that they gave rise to, the much more gracile Homo habilis? The answer has to lie in the psychological difference between the much quieter, love-immersed A. afarensis and A. africanus and the extrovert, boisterous bullying A. boisei and A. robustus and the introvert, sobered, quiet early adolescent H. habilis who will be described next.

Late Naughty Childman, A. robustus and A. boisei, had comparatively big frames with their skulls especially heavily built with very pronounced cranial and facial bone structures. Anthropologists know that these skull modifications were for the support of much stronger facial muscles used to work the heavy jaw and huge grinding teeth characteristic of these late australopithecines. The South African anthropologist Phillip Tobias describes them as having ‘their kitchen in their mouth’. Other anthropologists have described them as ‘the ultimate chewing machines’. We know from such evidence as the wear patterns on their teeth that the australopithecines were vegetarian but why did the later australopithecines need bigger grinding teeth? What change in diet occurred, and why? Being extrovert, increasingly naughty and roughly behaved they were like older children today who would rather be out playing than eating. Their problem was to fuel this extremely physically assertive and energetic lifestyle. Not being sufficiently conscious to attempt self-management all other animal species only exert enough energy to acquire their necessary food, space, shelter and a mate; energy wise they are conservative. With its rough play Late Naughty Childman was the first non-conservative energy user on Earth. To be able to ‘eat and run’ late childhood humans would have needed a readily available food source that they could eat quickly and, being vegetarian, they would have needed a lot of it because vegetables are not as efficient an energy source as meat for instance, which was not to appear on humanity’s dining table until upset developed. (While the australopithecines would have been capable of being rough, even possibly cruel at times to animals in their naughtiness they were not yet upset with innocence and thus practicing killing innocent animals regularly, which, as will be explained more fully shortly, is what so called ‘hunting’ was really all about for upset humans and what finally led to meat eating.) We can imagine certain edible varieties of nuts, hard-shelled fruits, fibrous roots and tubers best filling this need for a ready fuel supply, which explains the need for massive grinding teeth and accompanying facial structure. Compared to these late australopithecines H. habilis was an entirely different individual. An introspective deeply thoughtful and sobered person, no longer interested in physically intimidating the world H. habilis didn’t need great quantities of energy and thus food. Also no longer preoccupied with rough play there was much more time to gather what food was needed.

Another aspect of the fossil record of early humans is the overlap between the different varieties. For example in the biggest overlap by far there were still australopithecines in existence up to possibly 1.5 million years after H. habilis had appeared. Again this has been used as evidence that the late australopithecines branched Page 147 of

PDF Version away from the Homo line. Given we can now take into account what was happening psychologically, the overlapping becomes understandable. Just as there are very early models of cars still around today long after they have been superseded, so groups of early less intelligent varieties of humans carried on after they had been superseded. The best example of all of overlapping in the anthropological record is the existence today of remnants of our infant ape ancestors, namely the apes of today such as the gorillas and chimpanzees. Apes are not a branched development from the human line at all. They are on exactly the same development path but still at a much earlier stage. Even amongst these existing apes some are more advanced along the line of conscious development than others. The bonobos are far more neotenous and intelligent than the common chimpanzee or the gorilla.

Why overlap should be occurring especially between the different varieties of early humans is because to develop the next variety required the occurrence of a certain degree of intelligence for the next stage to take off. It takes a degree of intelligence, a degree of ability to understand the relationship between cause and effect, to challenge the instincts in the first place, which is when childhood emerges, and then it takes even more intelligence to begin to try to understand why we humans have not been ideally behaved, and then it takes further intelligence to accept that there isn’t any alternative other than resignation to living in denial of the human condition, and then, as will shortly be described, you have to be smart enough to turn the negative of resignation into a positive and get on with the corrupting task of searching for knowledge—and so on through all the stages. Without sufficient intelligence a child won’t be able to progress beyond childhood, or an adolescent progress beyond adolescence, etc. Certainly the human race has been stalled in adolescence but that wasn’t because the human race hadn’t become intelligent enough to progress beyond adolescence, rather, until science was developed, we lacked the insights with which to think of the explanation of the human condition.