The Great Exodus

33. Middle Demonstrative Childhood

This is our Middle Demonstrative Childman stage, the time when the intellect becomes demonstrative of the power of free will and experiences its first encounter with the frustration of the human condition.

The species: Australopithecus africanus—3 to 2 million years ago

The individual: 7 and 8 years old

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © 1991 Fedmex Pty Ltd

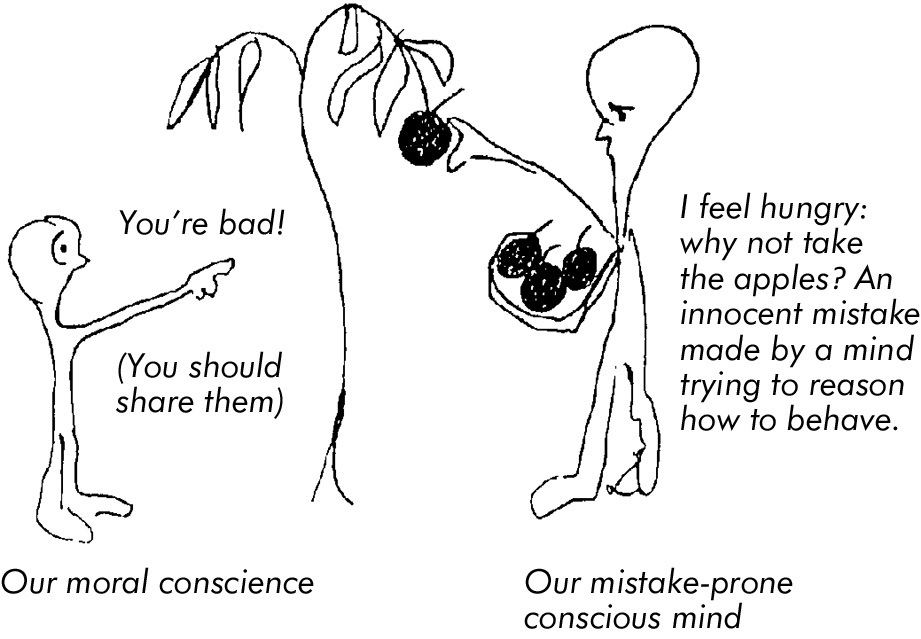

By mid-childhood consciousness is sufficiently able to make sense of experience to successfully manage and thus plan activities for not just minutes ahead but for hours and even days ahead. By mid-childhood consciousness’ ability to manage events had become sufficiently developed for an individual to be outwardly marvelling at, and demonstrative of its intellectual power. It is at this stage of active self-management that the outcomes of some experiments in self-adjustment begin to attract criticism from the instinctive self. ‘There are some apples; why shouldn’t I take them all for myself?’, an innocent mistake by a mind trying to reason how to behave, however the instinctive self orientated to behaving unconditionally selflessly makes the intellect aware that this is not the right way to behave. The emerging intellect has in effect been disobedient but the conscious self doesn’t know why it has ‘disobeyed’ the instincts, it isn’t able to understand and explain Page 143 of

PDF Version that it has become a conscious being. As well, the conscious self can’t stop ‘disobeying’ the instincts, it can’t stop thinking now that it is capable of it. While the conscious self can’t explain its actions it does know that what it is doing is not something it should stop doing, it is not something bad, it is not something deserving of this feeling of opposition coming from within itself. In fact the intellect is quite proud of its achievements in self-management as this demonstrative, middle childhood state is testimony to. Feeling frustrated the precursors of the defensive, retaliatory reactions of anger, egocentricity and alienation appear. Some aggressive ‘nastiness’ creeps into the conscious self’s behaviour. Also, in this situation of feeling unfairly criticised, any positive feedback reinforcement begins to be deliberately sought after, which is the beginning of egocentricity—the conscious thinking self or ego’s preoccupation with trying to defend its worth, assert that it is good and not bad. Further, the intellect begins experimenting in evading the unwarranted criticism. These early experiments in denial take the form of blatant lying. Lying is an art and to begin with we have little skill in it; we simply said, ‘but Mum, Billy told me to do it’. From being demonstrative of the power of free will the child has begun to feel the first real aggravations from the horror of the injustice of the human condition. Of course for children growing up during humanity’s australopithecine childhood, love would still have very much been the dominant influence in life overall and these defensive expressions of frustration would be restricted to feelings and actions rather than to words. In fact language wasn’t developed by our forebears until the early adolescent stage when alienation appeared and with it the need to somehow explain ourselves. As mentioned, Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin’s study of brain cases in fossil skulls for the imprint of Broca’s area (the word-organising centre of the brain) suggests ‘Homo had a greater need than the australopithecines for a rudimentary language’.