The Great Exodus

Page 107 of

PDF Version 23. Nurturing now becomes a priority

We can now at last explain and understand why the nurturing of our children became so compromised and neglected during the last 2 million years during humanity’s insecure adolescence, desperately fighting to establish its goodness and worth against all the indications that it was an evil blight on the planet. Since fighting and loving are opposing forces nurturing was always going to suffer but, as emphasised in the last section, if humanity didn’t fight ignorance humanity would self-destroy from perpetual ignorance and resulting terminal upset, in particular ever-increasing and ultimately intolerable levels of alienation. The best strategy that was possible was to leave one of the sexes relatively free from having to carry out the upsetting fight so they could retain some innocence to nurture the next generation, but that left that sex, namely women, struggling to appreciate the upsetting consequences of carrying out the fight. Women have tended to be soul-sympathetic rather than ego-sympathetic which left men unjustly condemned by women with all the awful consequences that that condemnation entailed, as described in the last section. All the horrors that occurred during humanity’s last 2 million years’ struggle through its insecure adolescent stage have in truth been so dreadful they are unthinkable and unspeakable—but now that terrible existence can be brought to an end and the nurturing of our children can again be given the priority it once enjoyed.

As has been emphasised, the importance of nurturing in the maturation of humanity and in our own lives (for our own maturation follows or recapitulates the path our species is undergoing) has been one of those extremely confronting truths, like integrative meaning, that humans have had no choice but to live in denial of. With the immense importance of nurturing now explained we can see that failing to nurture our children was tantamount to killing them, and although we haven’t been able to explain or acknowledge the importance of nurturing the truth is all humans have intuitively known how important it is. Clearly, while we had no means of explaining to ourselves or others why we were unable to adequately nurture our offspring—why we were in effect killing them—we had no choice other than to deny the truth of the importance of nurturing. No wonder, as has been quoted before, ‘people would rather admit to being an axe murderer than being a bad father or mother’. Since we can now finally explain the reason why we haven’t been able to adequately nurture our children we can now finally admit how important nurturing is; moreover, as part of the rehabilitation of humanity, that can and must take place.

Despite our historic need to deny the importance of nurturing, a number of books and articles have come out over the years that have attempted to broach the truth of the extent of the damage we cause our children by not nurturing them as much as their instincts expect. Understandably these attempts have very often been met by a ‘deaf’ public, by parents unable to cope with the condemnation and guilt that that truth causes. However now that we can and have to acknowledge the truth of the importance of nurturing, quotes from these books and articles can serve to resurrect that truth.

One book that has met with some public acceptance is Jean Liedloff’s 1975 book The Continuum Concept. This partial acceptance is no doubt due to the fact that Liedloff largely avoids the morality issue associated with the ideal state of altruistic, integrative, cooperative love involved in nurturing, stating simply that we need to give infants the caring treatment ‘which is appropriate to the ancient continuum of our species inasmuch as it is suited to the tendencies and expectations with which we have evolved’ (p.35 of 168) in order for them to have ‘a natural state of self-assuredness, well-being and joy’ (www.continuum-concept.org).

Page 108 of

PDF Version It should be mentioned that in The Continuum Concept Liedloff does recognise how the ever-increasing levels of alienation/ psychosis/ neurosis in humans (an escalation that will be explained in some detail later in this book) have destroyed our natural instincts for nurturing, saying ‘We have had exquisitely precise instincts, expert in every detail of child care, since long before we became anything resembling Homo sapiens. But we have conspired to baffle this longstanding knowledge so utterly that we now employ researchers full time to puzzle out how we should behave toward children, one another and ourselves’ (p.34 of 168).

As alluded to earlier, one of the most truthful and courageous acknowledgments of the importance of nurturing can be found in an article titled ‘The Social Necessity of Nurturance’, written by journalist Betty McCollister and published in the January 2001 edition of the Humanist journal. Here is an extract from this right-thinking, yet extremely confronting article: ‘the United States—a nation with 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prison population. We can somehow find money for jails but not for measures that could give our babies and children a good start in life and thus drastically reduce the need for such institutions…Will the nation follow California’s lead, as it so often does, and ultimately spend more on jails than on education?…Is there no other option?

Of course, there is. To find it we must first learn two fundamental things about our species: how we evolved into the large-brained Homo sapiens we are; and the nature of a mother’s role as primary caregiver. Once we understand these two factors we will be better able to determine how best to support her during pregnancy and lactation and how to enable her to give more of herself to her infant at least during the crucial first year, when the child’s brain doubles in size, and preferably for the first five years, while the brain trebles in size to attain three-fourths of its final growth. How did we become human? What brought our ancestors to the threshold between our animal ancestors and our hominid selves, which we crossed about four million years ago? We can’t even begin to solve in any meaningful way our multiple, interlocking social pathologies except from the perspective of our evolution…evolution is the unifying principle that…explains how we descended from our ape ancestors. It offers us clues as to what is going amiss and why…

Our ancestors lived in closely-knit tribes in which cooperation and loyalty were essential. It was within that matrix—with devoted infant care and strong interpersonal links—that the brain enlarged from the size of a chimpanzee’s to double that in Homo erectus and quadruple that in… ourselves…Clearly, then, leaving mothers to cope entirely on their own flouts everything inherent to our nature and risks disastrous results.

A look at our hominid past helps us to understand our pathological present. About four million years ago, one line of apes assumed bipedal posture. This freed the hands, with their opposable thumbs, for grasping, which brought eye-hand coordination which led to larger brain development, for which nature selected. However, because the birth canal could dilate only so far and the pelvic girdle not at all in bipeds, the skull had to mature after birth. The hominid solution was to bear increasingly unfinished infants who required increasingly intensive and extensive care. Lacking instincts to make them self-sufficient, the young required assiduous nurture. This pattern continued with the resultant cycle of increased helplessness; need for more care, more social interaction, more communication; formation of more complex and larger brains; demand for even more nurture.’ This is a grand effort to get to the bottom of the fundamental question of how we became human; however the prolonged infancy and exceptional need for nurturing wasn’t a result of the increased brain size and birth canal limitations forcing infants to be born early, rather it was a result of the love-indoctrination process. The large brain didn’t develop until after the extended infancy and intense nurturing took place as evidenced by the bonobos, who don’t have a very large brain but are intensely nurturing and already neotenous. Also, as will be explained in Section 24, ‘What is consciousness?’, Page 109 of

PDF Version what promoted a conscious, intelligent, larger brain wasn’t the availability of hands to manipulate the world, but love-indoctrination training of the brain in selflessness.

McCollister continues: ‘Thus we became a species whose helpless newborns must have others on hand for them twenty-four hours a day, preeminently the mother due to her ability to breastfeed…the bonding between mother and child…lays the foundation for future growth…Our evolution has resulted in a species whose infants can’t thrive without continual, loving attention. Here, then, is the clue to raising fewer unhappy, alienated, violent youth for jail fodder…Every human infant must have unconditional love; without it, an infant’s health and growth will be stunted… Anthropologists, neurologists, child psychiatrists, and all other researchers into child development unequivocally agree and have sought for decades to alert society.

For example: …Ashley Montagu (anthropologist): “The prolonged period of infant dependency produces interactive behavior of a kind which in the first two years or so of the child’s life determines the primary pattern of his subsequent social development.” Alfred Adler (psychiatrist): “It may be readily accepted that contact with the mother is of the highest importance for the development of human social feeling…” Selma Fraiberg (child psychologist): A baby without solid nurturing “is in deadly peril, robbed of his humanity.”…George Wald (biologist): “We are no longer taking good care of our young…” Ian Suttie (psychoanalyst): “…The infant mind…is dominated from the beginning by the need to retain the mother—a need which, if thwarted, must produce the utmost extreme of terror and rage.”…James Prescott (neuropsychologist): Monkey juveniles “deprived of their mothers were at times apathetic, at times hyperactive and given to outbursts of violence [is this not the equivalent of attention deficit disorder?]…showed behavioral disturbances accompanied by brain damage…” Richard M. Restak (neurologist): “Scientists at several pediatric research centers across the country are now convinced that failure of some children to grow normally is related to disturbed patterns of parenting.” Sheila Kippley (La Leche League): “It is obvious that nature intended mother and baby to be one…”

In the face of such overwhelming, unanimous testimony, can we doubt that we are failing our children? The dismal truth is that, on the whole, babies received more and better care 25,000 years ago, 250,000 years ago, even 2.5 million years ago, than many do today…To correct this, we must first recognize that, while both parents play vital roles in an infant’s development, the mother—like it or not—is the primary caregiver. Biologically, that’s how the system works. And such an immeasurably important task cannot be sustainably carried out in her “spare time.”…Humanity was geared for females to cherish offspring in the womb, bond with them at birth, and lavish love on them at the breast. It isn’t sexist to esteem motherhood. It is sexist to trivialize it [as the feminist movement has frequently done]…Grasping the connection between negligent infant care and adolescent violence…we are obliged to act…Alienated, with low self-esteem, pessimistic about the future, in schools that don’t educate, the children who should be our hope for the future instead drink, smoke, take drugs, get pregnant, commit suicide, and commit crimes which land them in our awful jails.’

For all her exceptional sensibility and right-thinking, McCollister hasn’t delved to the bottom of the problem and asked the question screaming to be addressed: ‘But why have humans stopped loving their infants?’ There may be a legitimate reason for why and without that reason understood all efforts to properly nurture children may be futile. In fact, as has been emphasised, there is a legitimate reason why nurturing has been so compromised, and the understanding of that reason, namely the unavoidable and necessary battle between intellect and instinct that emerged during humanity’s adolescence, is the only way the disrupting battle can subside and nurturing can be given the consideration it requires. Over the years there have been numerous movements started that identify the lack of nurturing as the cause of society’s problems and which call for greater emphasis on nurturing, such as the Touch the Future organisation, the Leidloff Page 110 of

PDF Version Continuum Network and the Natural Child Project; however while the deeper issue of why humans have been unable to nurture was left unaddressed and unanswered it was impossible to bring about any real change to the problem of the inadequate nurturing of children.

Of course the imposition of the battle between our instinct and intellect had repercussions beyond that of impairing a mother’s ability to focus on the nurturing of her infants. Since this battle only emerged some 2 million years ago, and only became extreme towards the end of those 2 million years, the great majority of human history—from the australopithecines through to the advent of Homo sapiens sapiens—was spent living cooperatively. This means infants now enter the world firstly expecting it to be one of gentleness and love, and secondly with almost no instinctive expectation of encountering a massively upset, embattled world. It is the extreme contrast between our species’ instinctive memory of a harmonious, happy, secure, sane, all-loving and all-sensitive matriarchal world, and our species’ more recent massively embattled angry, egocentric and alienated patriarchal world, that makes the shock infants must experience entering the world now so psychologically damaging. We have been living in denial of both the truth that our ancestors lived in a state of total love and that we are currently living in a state of near complete corruption of that ideal instinctive world of our soul. As a result of these two denials we haven’t been aware of how devastating it must be for infants to encounter our world. The whole issue of the extreme innocence of children and extreme lack of it in adults needs to be taken into account when thinking about childhood. Playwright Samuel Beckett was only slightly exaggerating the brevity today of a truly soulful, happy, innocent, secure, sane, human-condition-free life when he wrote, ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’ (Waiting for Godot, 1955). To describe the shock effect of innocence’s encounter with our human-condition-afflicted, upset, corrupt, alienated, neurotic, selfish, angry, false world, R.D. Laing borrowed words from the 19th century French poet Stéphane Mallarmé: ‘L’enfant abdique son extase’, ‘To adapt to this world the child abdicates its ecstasy’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p.118 of 156). In Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, William Wordsworth spoke of ‘something that is gone / …Whither is fled the visionary gleam? / Where is it now, the glory and the dream? // Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting’. The contrast between what a child’s innocent, love-saturated instincts expect and what the child encounters in our human-condition-afflicted, massively upset, soul-butchered world is so great it is akin to a flower finding itself having to grow in a dark cesspit. No wonder as adults we turned out as gnarled thornbushes, ready to stunt the next generation—thank God the human condition can now end.

It should also be pointed out that except for one reference to ‘unconditional love’, McCollister’s account of the importance of nurturing makes no mention of the training in altruism and resulting morality that is the true purpose and significance of nurturing. The love-indoctrination process is not recognised; it is in fact being blatantly denied for it is an insight readily deduced from the information presented. Such is the extent of the denial/ alienation in the human make-up now. As novelist Aldous Huxley said about the insecurity of our human condition, ‘We don’t know because we don’t want to know’ (Ends and Means, 1937, p.270).

Again, without the understanding necessary to ameliorate that insecurity, it has been psychologically unsafe to acknowledge the importance of nurturing as both an instinctive expectation, and as the creator of our sense of morality. Admitting to our inability to adequately relate and be affectionate to our children, as McCollister bravely does, is in itself confronting enough, let alone having to face the truth of the integrative, cooperative ideal state that children’s instinctive selves expect. There is guilt enough in just attempting Page 111 of

PDF Version to be a loving parent without also having to face the truths of integrative meaning, our integratively-orientated, ideal-world-aware soul, and our own corrupted condition. The purity and innocence of children has the potential to expose us terribly. Referring to children as ‘kids’ was really a derogatory, retaliatory ‘put down’, a way of holding their confronting innocence at bay. The quotes included in this section about the importance of nurturing are amongst the bravest that exist on this subject and even they comply with this position of avoiding the real significance of nurturing, which is the training of altruism.

As mentioned, with the arrival of understanding of the human condition those brave books that did at least acknowledge the importance of nurturing will prove especially useful in learning as much as we can about nurturing. One particular example of a work that discusses the importance of nurturing and the psychological impact of the failure to do so is the 1996 book Thinking About Children, a posthumous publication of some of the papers of the renowned British paediatrician, child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, D.W. Winnicott, who is described on the book’s dust jacket as someone who is ‘increasingly recognized as one of the giants of psychoanalysis’. In this book Winnicott states: ‘There are certain difficulties that arise when primitive things are being experienced by the baby that depend not only on inherited personal tendencies but also on what happens to be provided by the mother. Here failure spells disaster of a particular kind for the baby. At the beginning the baby needs the mother’s full attention…in this period the basis for mental health is laid down [p.212 of 343] …the essential feature [in a baby’s development] is the mother’s capacity to adapt to the infant’s needs through her healthy ability to identify with the baby. With such a capacity she can, for instance, hold her baby, and without it she cannot hold her baby except in a way that disturbs the baby’s personal living process [p.222].’

In 1967 psychologist Bruno Bettelheim wrote an honest book about autism, titled The Empty Fortress in which he claimed autism resulted from overwhelmingly negative parents interacting with infants’ susceptibility during critical early stages in their psychological development. He coined the term ‘refrigerator mothers’ for the cold-heartedness of what we can now understand is essentially all humans’ unavoidable-after-2-million-years-of-struggle, human-condition-afflicted, immensely alienated, neurotic state. Of course while humanity hasn’t been able to explain upset denial has been the only way of coping, and the denial of choice for avoiding having to admit to our inability to nurture our offspring has been to blame genes, and sometimes chemicals, for the effects that inadequacy has on our offspring. It was mentioned in Section 13 that genes are being blamed for every kind of ailment. It is true, there are now said to be genes for depression, drug addiction, violence, obesity, delinquency, learning and sleep disorders, suicide, sex addiction, paedophilia, homosexuality, and almost every other human malaise and abnormality—including for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and for those more extreme forms of ADHD, namely autism and schizophrenia. Even though we haven’t been able to admit it, everyone intuitively knows that our malaise are, in the main, the result of the psychological struggles we humans have as a result of our variously upset, insecure, human-condition-afflicted upbringings and lives. The truth is our psychoses and their many physical manifestations are not about our genes but rather the death of our soul. In fact the word ‘psychiatry’ literally means ‘soul healing’, coming as it does from the Greek words psyche, meaning soul, and iatreia, meaning healing. In the case of autism, a 2006 Time magazine feature article about this particular childhood disorder acknowledged the rapidly increasing levels of autism in the western world in particular, quoting that ‘According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1 in 166 American children born today will fall somewhere on the autistic spectrum. That’s double the rate of 10 years ago and 10 times the estimated incidence a generation ago’ (Claudia Wallis, 15 May 2006). The article then said that ‘most researchers believe autism arises from a combination of genetic Page 112 of

PDF Version vulnerabilities and environmental triggers’. Nowhere in the feature article was lack of love cited as a possible cause, but again how could parents possibly cope with having to accept such an explanation—they ‘would rather admit to being an axe murderer than being a bad father or mother’. Blaming genes has been infinitely more bearable than blaming our alienation from our true, natural selves and our resulting inability to adequately nurture our offspring. The problem is this extreme dishonesty means there has been no analysis of what is really going on in our human world. We are not learning anything about ourselves. Lying is a form of madness, insanity, stupidity, ultimately of self-destruction. As Berdyaev was quoted as saying at the very beginning of this book, ‘knowledge requires great daring’. If we want to stop the ‘doubl[ing] rate’ every ‘10 years’ of the ‘incidence’ of childhood disorders and resulting adult dysfunction in the world we have to get real/ honest. What makes honesty possible for everyone now is that being able to explain the human condition means we can understand that being alienated/ neurotic was not a criminal state, something to be ashamed of, but rather an unavoidable end result of humanity’s necessary, heroic search for knowledge.

The truth about the spiralling increase in the incidence of ADHD, autism and schizophrenia in society, is that it is a direct result of the levels of alienation in society having increased to extreme levels. The exponential increase of upset and alienation in society will be explained and documented in some detail later in this book but the truth is the levels of alienation in society now are such that pretty well all humans are but cardboard cut-outs of what they would be like free of the human condition. While adults aren’t aware of their immensely embattled, upset, alienated—virtually dead—condition because they are living in denial of it, new generations of children arriving into the adult world who have yet to adopt adults’ strategy of denial can fully see the difference between the original, ideal, innocent instinctive state and the immensely upset alienated state and somehow have to cope with the distress it causes them. The ‘Resignation’ chapter in A Species In Denial describes how adolescents go through an agonising process of adopting humans’ historic strategy for coping with the human condition of resigning themselves to a life of living in denial of it and any truths that bring it into focus, but until a young person has adopted this defence they remain exposed to the full horror of the dilemma of the human condition. Having not yet adopted this denial children have always struggled mightily with the imperfection of the upset world they can see around them but with the gulf between humans’ original innocent state and our current immensely upset, alienated state being so great now, new generations find the gulf almost unbearable, and for increasing numbers of children actually unbearable. The truth is ADHD and its more extreme states of autism and schizophrenia are varieties of childhood madness. R.D. Laing got to the heart of the matter of madness when he famously said, ‘Insanity is a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world’. An unevasive analysis of autism is given by D.W. Winnicott in his book Thinking About Children: ‘Autism is a highly sophisticated defence organization. What we see is invulnerability…The child carries round the (lost) memory of unthinkable anxiety, and the illness is a complex mental structure insuring against recurrence of the conditions of the unthinkable anxiety [pp.220, 221 of 343]…It might be asked, what did I call these cases before the word autism turned up? The answer is…“infant or childhood schizophrenia” [p.200]’. Revealingly, the word schizophrenia literally means ‘broken soul’; to quote R.D. Laing again, ‘Perhaps we can still retain the now old name, and read into it its etymological meaning: Schiz—“broken”; Phrenos—“soul or heart”’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p107 of 156).

What has made it especially difficult for new generations trying to cope with our corrupted adult world is that adults have been unable to admit to being corrupted in soul, in fact, as pointed out, adults haven’t even been aware that they are corrupted—if Page 113 of

PDF Version adults were aware they were corrupted and alienated they wouldn’t be alienated, they wouldn’t have blocked out and thus protected themselves from the truth of their upset condition. With new generations able to clearly see the extent of the corruption and alienation in the world around them, this lack of any honesty by adults—in effect denial that there is anything wrong with them or their adult world—left children dangerously prone to blaming themselves. In encounters between the innocent and the alienated where the alienated say in effect there is nothing wrong with them or their world, in the innocents’ instinctive state of total trust and generosity they are left believing there must be something wrong with them, that in some way or other they must be at fault. In their immense naivety about the upset, alienated world, together with their great love, trust and generosity, innocents question their own view, not the view being presented by the alienated. The innocent do not know people lie because lying did not exist in our species’ original innocent instinctive world. The innocents’ trusting nature made them codependent to the alienated, susceptible to believing the alienated are right rather than accepting their own view of the situation. The destructive effects of lies upon others was once called ‘addiction via association’ but, as just mentioned, it is now known of as the problem of codependency, ‘the dependency on another to the extent that independent action or thought is no longer possible’. Children come from such an innocent, wholesome, trusting, loving, generous, integrative instinctive world that they all too readily blame themselves in situations where they are faced with a denial. Then, when they decide they must be at fault, their sense of self-worth and meaning is completely undermined and to cope with that ‘unthinkable anxiety’, as Winnicott accurately described it, they have no choice but to psychologically split themselves off from the perceived reality, adopt a state of ‘invulnerability’. This dialogue from the 1993 film House of Cards spoke the truth: ‘People say about the following categories that these kids have a problem or are disabled, or psychologically dumb, etc, but really they are children, through hurt or some kind of trauma, that have held onto soul, and not wanted to partake in reality—retarded, autistic, insane, schizophrenic, epileptic, brain-damaged, possessed by devils, crocked babies.’ We can see here another reason why the truth of an utterly integrated, loving, all-sensitive past and present instinctive soulful state in us was now such a confronting and exposing truth and why adults were so much more comfortable believing that our species’ instinctive past was a brutish and aggressive one. Again, the ‘Resignation’ chapter in A Species In Denial describes in some detail how much adults’ dishonesty and silence about the truth of their corrupted condition has devastated children. Thankfully the adult world can now tell children the truth about their immensely upset condition and that honesty alone is going to make an enormous difference to the psychological wellbeing of future generations.

One of the problems of not being able to be truthful about the real cause of childhood madness is that treatment of it can be dangerously misdirected. A 2006 report about the alarming increase in childhood disorders said, ‘Truly alarming evidence from pharmaceutical prescriptions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) drugs shows that in 2005 one in 25 children in many poorer areas of Australia suffer from ADHD’ (The Daily Telegraph, 13 June 2006); another article emphasised that, ‘Because it is so convenient and guilt-relieving to be able to attribute a child’s difficult behaviour to a neurochemical problem rather than a parenting or broader social one, there is a risk that this problem will become dangerously over-medicalised’ (The Australian, 8 Dec. 1997).

In his extremely brave 1970 book The Primal Scream, world leading psychologist Arthur Janov dealt head-on with the consequences of parents’ inability to love their children with anything like the amount of love children received before the intruding battle of the human condition emerged. Note the acknowledgment of the extent of the denial Page 114 of

PDF Version that sets in to cope with becoming extremely corrupted: ‘Anger is often sown by parents who see their children as a denial of their own lives. Marrying early and having to sacrifice themselves for years to demanding infants and young children are not readily accepted by those parents who never really had a chance to be free and happy [p.327 of 446] …neurotic parents are antifeeling, and how much of themselves they have had to cancel out in order to survive is a good index of how much they will attempt to cancel out in their children [p.77] …there is unspeakable tragedy in the world…each of us being in a mad scramble away from our personal horror. That is why neurotic parents cannot see the horror of what they are doing to their children, why they cannot comprehend that they are slowly killing a human being [p.389] …A young child cannot understand that it is his parents who are troubled…He does not know that it is not his job to make them stop fighting, to be happy, free or whatever…If he is ridiculed almost from birth, he must come to believe that something is wrong with him [p.60] …Neurosis begins as a means of appeasing neurotic parents by denying or covering certain feelings in hopes that “they” will finally love him [p.65] …a child shuts himself off in his earliest months and years because he usually has no other choice [p.59] …When patients [in primal therapy] finally get down to the early catastrophic feeling [the ‘primal scream’] of knowing they were unloved, hated, or never to be understood—that epiphanic feeling of ultimate aloneness—they understand perfectly why they shut off [p.97] …Some of us prefer the neurotic never-never land where nothing can be absolutely true [the postmodernist philosophy] because it can lead us away from other personal truths which hurt so much. The neurotic has a personal stake in the denial of truth [p.395]’.

It is worth including the following quote to illustrate how this extreme ‘personal stake in the denial of truth’ has manifested itself in mechanistic science. In his 1989 book Peacemaking Among Primates, Frans de Waal records: ‘For some scientists it was hard to accept that monkeys may have feelings. In [the 1979 book] The Human Model…[authors] [Harry F.] Harlow and [Clara E.] Mears describe the following strained meeting: “Harlow used the term ‘love’, at which the psychiatrist present countered with the word ‘proximity’. Harlow then shifted to the word ‘affection’, with the psychiatrist again countering with ‘proximity’. Harlow started to simmer, but relented when he realized that the closest the psychiatrist had probably ever come to love was proximity.”’

In his 2002 book They F*** You Up: How to Survive Family Life, child psychologist Oliver James acknowledges that ‘Our first six years play a critical role in shaping who we are as adults’, and says ‘One of our greatest problems is our reluctance to accept a relatively truthful account of ourselves and our childhoods, as the polemicist and psychoanalyst Alice Miller pointed out’ (Intro), and that ‘believing in genes [as the cause of psychoses] removes any possibility of “blame” falling on parents’ (ch.1).

The following dialogue from the 1989 film Parenthood uses humour to illustrate how our near total inability to be honest has impaired any advance in science: Counsellor: ‘He’s a very bright, very aware, extremely tense little boy who is only likely to get tenser in adolescence. He needs some special attention.’ Karen: ‘It’s because he was first.’ Counsellor: ‘Hm?’ Karen: ‘It’s because he was our first. I think we were very tense when Kevin was little. I mean, if he got a scratch, we were hysterical. By the third kid, you know, you let him juggle knives.’ Counsellor: ‘On the other hand, Kevin may have been like this in the womb. Recent studies indicate that these things are all chemical.’ Gil: ‘[points at Karen] She smoked grass.’ Karen: ‘Gil! I never smoked when I was pregnant…Will you give me a break?’ Gil: ‘But maybe it affected your chromosomes.’ Counsellor intervening: ‘You should not look on the fact that Kevin will be going to a special school as any kind of failure on your part.’ Gil: ‘Right, I’ll blame the dog.’

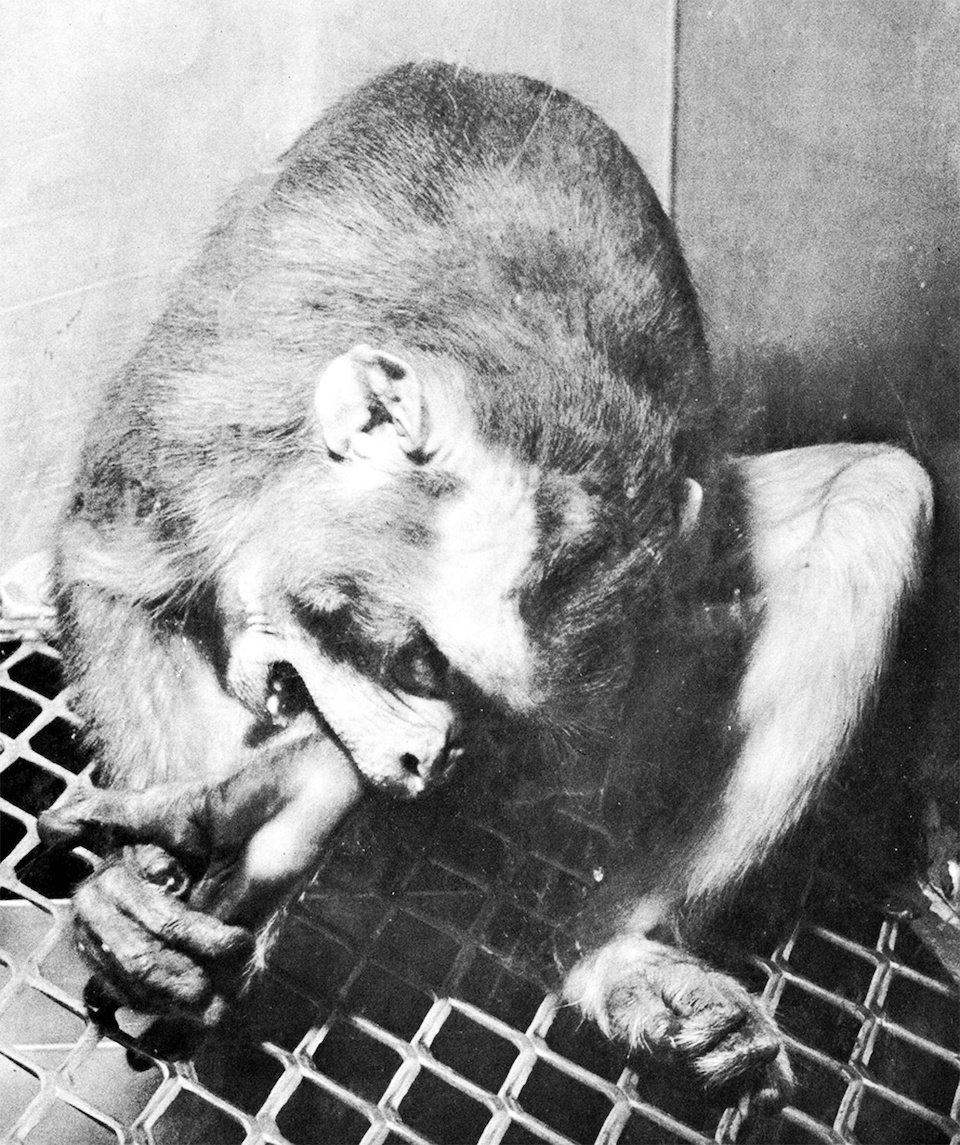

The quote from Frans de Waal mentioned the work of Harry F. Harlow, an American psychologist who in the 1950s studied the effects of isolation and touch deprivation on rhesus monkey infants using surrogate wire and cloth mothers. While these experiments did show the importance of affection and nurturance on psychological development they Page 115 of

PDF Version were unethical and if it wasn’t for our inability to confront and acknowledge truths that we all actually know, in this instance the critical importance of nurturing, there would never have been a need to find such stark evidence for the importance of nurturing. Harlow found that a new-born monkey raised on a bare, wire-mesh cage floor survived with difficulty, if at all, during its first five days of life. In an even more extreme experiment he found that monkeys raised in total isolation in a small metal chamber he called the ‘pit of despair’ developed the most extreme symptoms of what we recognise as human depression and schizophrenia and, as adults, were unable to raise offspring. At the same time a psychologist at Yerkes Primate Centre in America named Richard Davenport was rearing baby chimpanzees alone in small boxes for two years at a time. The isolated chimps soon developed stereotypies such as rocking and head banging. The photo below is of a monkey Harlow raised in partial isolation from birth to six months which developed severe behavioural abnormalities. The photo shows the fully-grown animal biting itself at the photographer’s approach.

In an address titled The Nature of Love, delivered by Harlow on 31 August 1958 on his election as President of the American Psychological Association, Harlow made this opening observation which reinforces what was said earlier about science’s inability to consider the issue of love: ‘Psychologists, at least psychologists who write textbooks, not only show no interest in the origin and development of love or affection, but they seem to be unaware of its very existence. The apparent repression of love by modern psychologists stands in sharp contrast with the attitude taken by many famous and normal people. The word “love” has the highest reference frequency of any word cited in Bartlett’s book of Familiar Quotations’ (first pub. in American Psychologist, 1958, 13, pp.573—685).

The last word on the importance of nurturing is best left to Olive Schreiner who, in The Story of an African Farm, wrote: ‘They say women have one great and noble work left them, and they do it ill…We bear the world, and we make it. The souls of little children are marvellously delicate and tender things, and keep for ever the shadow that first falls on them, and that is the mother’s or at best a woman’s. There was never a great man who had not a great mother—it is hardly an exaggeration. The first six years of our life make us; all that is added later is veneer…The Page 116 of

PDF Version mightiest and noblest of human work is given to us, and we do it ill’ (p.193 of 301). This quote calls to mind a line from the 1996 TV-movie An Unexpected Family, when the judge involved in the drama says, ‘every problem we have in this world is because a child wasn’t loved’. Like Schreiner’s quote, this comment lays all the blame for the ills of the world on the lack of nurturing children receive but the truth is the origin of ‘every problem we have in this world’ is the upsetting battle that broke out between our conscious self and instinctive self and that the ‘mightiest’, most important ‘human work’ has actually been to defeat the ignorance of our instinctive self as to the fact of our species’ fundamental goodness. It was this battle that men were largely responsible for that unavoidably relegated nurturing to a secondary position of importance in human endeavours. Not only were men preoccupied with their fight, women had to help men and also take on a role of inspiring them with their image of innocence, their object beauty. As emphasised in the previous section, women have had to inspire love when they were no longer innocent, ‘keep the ship afloat’ when men crumpled—all the while attempting to nurture a new generation while oppressed by men who could not explain why they were dominating, or why they were so upset and angry. This was an altogether impossible task, yet women have done it as best they could for 2 million years.

The hitherto unacknowledged, unexplained and all-important, guilt-lifting reason why women have only been able to ‘do’ the task of nurturing ‘ill’ is because of the unavoidable and necessary intrusion of the battle of the human condition. With the human condition now solved our species’ priority can return to the nurturing of our infants; in fact it now becomes a matter of great urgency that humanity does so.

To return to the story of the emergence of the upset state of our human condition. It has now been explained that, unlike birds, our original instinctive orientation was to behaving cooperatively. It will shortly be explained that this particular instinctive orientation had a dramatic compounding effect on the upset we humans felt from having defied our instincts. When we became upset that upset was itself at odds with the cooperative ideals that we had become orientated to, and this extra criticism greatly fuelled our upset. We weren’t out of step with some instinctive flight path, we appeared to be out of step with the cooperative meaning of life, with ‘God’ no less.

In order to explain the horror of this compounding effect our particular instinctive orientation had on our upset it first needs to be explained how and when humans managed to become the fully conscious beings that challenged their instincts and became upset in the first place.