The Great Exodus

9. What then is the biological explanation for the human condition?

What then is the answer to this question of questions, this problem of good and evil in the human make-up, this dilemma of the human condition? What is the ‘origin of sin’? What caused us to become divisively behaved and how is this divisive behaviour brought to an end?

In the aforementioned sonnet No Worst, There is None, Gerard Manley Hopkins summarised the suicidally deep depression that faced virtually anyone crazy enough to dare attempt to plumb the terrifying depths of the issue of the human condition with the words, ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed’. It is true that until now the great riddle of all riddles of the existence of good and evil in our human make-up hasn’t been able to be understood, or ‘fathomed’, and that as a result near total denial of the subject has been the only means to cope with it. What has happened to change all this is that science has finally made it possible to explain and unravel the riddle; it has enabled us to understand that when humans became fully conscious and able to wrest management of our lives from our instincts, our instincts resisted this takeover and that it was this opposition that unavoidably led to the ‘corrupted’, upset angry, egocentric and alienated state of our human condition. Further, it is this ability now to understand how we became upset that allows that upset state to subside.

As will be explained much more fully in Section 24, ‘What is Consciousness?’, what distinguishes humans from other animals is our fully conscious state, our ability to understand and thus manage the relationship between cause and effect. However prior to becoming fully conscious and able to self-manage—consciously decide how to behave—humans were controlled by and obedient to our instincts, as other animals still are. As novelist Aldous Huxley acknowledged, ‘Non-rational creatures do not look before or after, but live in the animal eternity of a perpetual present; instinct is their animal grace and constant inspiration; and they are never tempted to live otherwise than in accord with their own…immanent law’ (The Perennial Philosophy, 1946).

It was science’s discovery of the existence of nerves and genes and how they work that enabled us to understand that, unlike the gene-based learning system, the nerve-based learning system can associate information, reason how experiences are related and learn to understand and become conscious of the relationship of events that occur through time. The gene-based learning system, on the other hand, can orientate species to situations but is incapable of insight into the nature of change. Genetic selection of one reproducing individual over another reproducing individual (in effect, one idea over another idea, or one piece of information over another piece of information) gives species adaptations or orientations—instinctive programming—for managing life, but those genetic orientations, those instincts, are not understandings.

It follows then that when our conscious mind emerged it was neither suitable nor sustainable to be orientated by instincts. It had to find understanding to operate effectively and fulfil its great potential to manage life. However, when the conscious mind began to Page 29 of

PDF Version exert itself and experiment in the management of life from a basis of understanding in the presence of already established instinctive behavioural orientations, a battle broke out between the two.

Our intellect began to experiment in understanding as the only means of finding out the correct and incorrect understandings for managing existence, yet the instincts, being in effect ‘unaware’ or ‘ignorant’ of the intellect’s need to carry out these experiments, ‘opposed’ any understanding-produced deviations from the established instinctive orientations. The instincts in effect ‘criticised’ and ‘tried to stop’ the conscious mind’s necessary search for knowledge. Unable to understand and thus explain why these experiments in self-adjustment were necessary, the intellect was unable to refute this implicit criticism from the instincts. The unjust criticism from the instincts ‘upset’ the intellect and left it with no choice other than to simply defy ‘opposition’ from the instincts.

The intellect’s defiance expressed itself in three ways: it attacked the instincts’ unjust criticism, tried to deny or block from its mind the instincts’ unjust criticism, and attempted to prove the instincts’ unjust criticism wrong. Humans’ upset angry, alienated and egocentric state—precisely the divisive condition we suffer from—appeared. (Note, the Concise Oxford Dictionary defines ‘ego’ as ‘the conscious thinking self’, so ego is another word for the intellect. Thus the word ‘egocentric’ means the intellect became centred or focused on trying to prove the instincts’ criticism wrong; it became focused on trying to prove its worth, prove that it was good and not bad.)

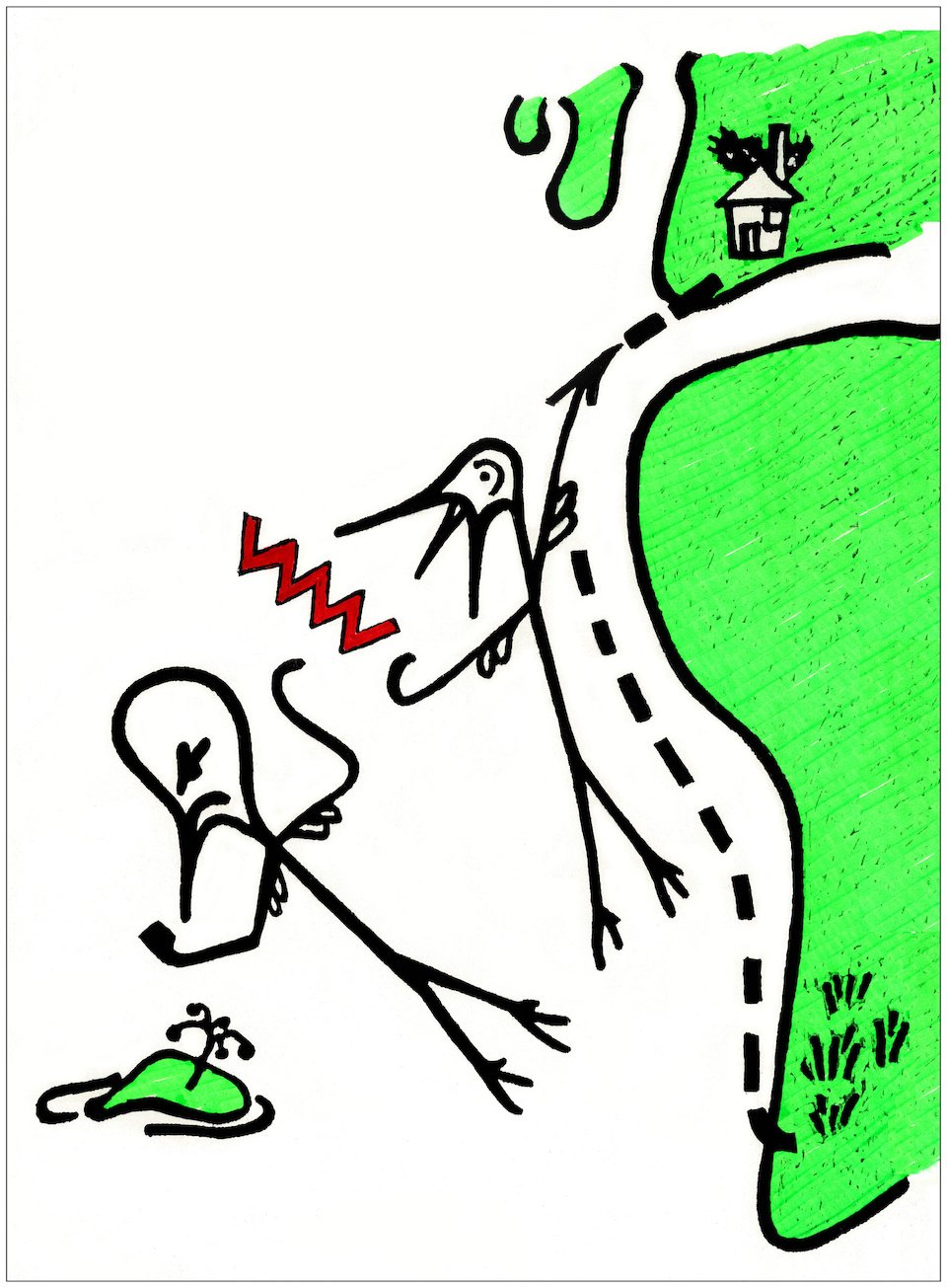

The following analogy serves to clarify what took place.

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © Fedmex Pty Ltd 1991

Many bird species are perfectly orientated to instinctive migratory flight paths. Each winter, without ever ‘learning’ where to go and without knowing why, they quit their established breeding grounds and migrate to warmer feeding grounds. They then return Page 30 of

PDF Version each summer and so the cycle continues. Over the course of thousands of generations and migratory movements, only those birds that happened to have a genetic make-up that inclined them to follow the right route survived. Thus, through natural selection, they acquired their instinctive orientation.

Consider a flock of migrating storks returning to their summer breeding places on the rooftops of Europe from their winter feeding grounds in southern Africa. Suppose that in the instinct-controlled brain of one of them (we will call him Adam) we place a fully conscious mind. As Adam flies north, he sees an island off to the left laden with apple trees.

Using his newly acquired conscious mind Adam thinks, ‘I should fly down and eat some apples’. It seems a reasonable thought but he can’t know if it is a good decision or not until he acts on it. For his new thinking mind to make sense of the world he has to learn by trial and error and decides to carry out his first grand experiment in self-management by flying down to the island and sampling the apples.

But it’s not that simple. As soon as he deviates from his established migratory path, his instinctive self tries to pull him back on course. In effect it criticises him for veering off course, condemns his search for understanding. Adam is in a dilemma. If he obeys his instinctive self and flies back on course, he will be perfectly orientated but he’ll never learn if his deviation was the right decision or not. All the messages he’s receiving from within tell him that obeying his instincts is good, is right. But there’s also a new message of disobedience, a defiance of instinct. Going to the island will bring him apples and understanding, yet he already sees that doing so will also make him feel bad.

Uncomfortable with the criticism his conscious mind or intellect is receiving from his instinctive self, Adam’s first response is to ignore the apples and fly back on course. This makes his instinctive self happy and wins the approval of his fellow storks, for not having conscious minds they are innocent, unaware or ignorant of the conscious mind’s need to search for knowledge. They are obeying their instinctive selves by following the flight path past the island.

Flying on however, Adam realises he can’t deny his intellect. Sooner or later he must find the courage to master his conscious mind by carrying out experiments in understanding. This time he thinks, ‘Why not fly down to an island and have a rest?’ Not knowing any reason as to why he shouldn’t, he proceeds with his experiment. Again his instinctive self criticises him for going off course.

This time he defies the criticism and perseveres with his experimentation in self-management. But it means he has to live with the criticism and is immediately condemned to a state of upset. A battle has broken out between his instinctive self, perfectly orientated to the flight path, and his emerging conscious mind, which needs to understand why that is the correct path to follow. His instinctive self is perfectly orientated, but he doesn’t understand that orientation.

As mentioned earlier, when the fully conscious mind emerged it wasn’t enough for it to be orientated by instincts. It had to find understanding to operate effectively and fulfil its great potential to manage life. Tragically, the instinctive self didn’t ‘appreciate’ that need and ‘tried to stop’ the mind’s necessary search for knowledge, as represented by the latter’s experiments in self-management. Hence the ensuing battle between instinct and intellect.

To refute the criticism from his instinctive self, Adam needed to understand the difference in the way genes and nerves process information, yet he had only just taken the first steps in the search for knowledge. It was a catch-22 situation for the fledgling thinker. In order to explain himself, he needed the very understanding he was setting out to find. He had to search for understanding, ultimately self-understanding, understanding Page 31 of

PDF Version of why he had to ‘fly off course’, without the ability to explain why. He couldn’t defend his actions. He had to live with the criticism from his instinctive self and, without that defence, was insecure in its presence.

But what could he do? If he abandoned the search he’d gain some momentary relief, but the search would nevertheless remain to be undertaken. All he could do was retaliate against the criticism, try to prove it wrong or simply ignore it, and he did all of those things. He became angry towards the criticism. In every way he could he tried to demonstrate his worth—to prove that he was good and not bad. And he tried to block out the criticism. He became angry, egocentric and alienated or, in a word, upset.

Adam found himself in an extremely difficult position. We can see that while Adam was good he appeared to be bad and had to endure the associated upset until he found the defence or reason for his mistakes. Suffering upset was the price of his heroic search for understanding; it was an inevitable outcome in the transition from an instinct-controlled state to an intellect-controlled state. His uncooperative, divisive aggression and his selfish, egocentric efforts to prove his worth and his need to deny and evade criticism became an unavoidable part of his personality. Such was his predicament, and such has been the human condition.

This analogy is similar to the Biblical account presented in Genesis of the Garden of Eden where Adam and Eve ‘eat [the fruit] from the tree of knowledge’ (2:17) that was ‘desirable for gaining wisdom’ (3:6)—go in search of understanding—and as a result were demonised and ‘banished…from the Garden’ (3:23). In short, when we went in search of understanding our upset, corrupted, ‘fallen’, supposedly ‘guilty’ state emerged. In this presentation however Adam and Eve are not the banishment-deserving, evil, worthless, guilty villains they are portrayed as in Genesis but immense HEROES. They had to go in search of knowledge and defy ignorance. Our instincts had in effect no sympathy for the pursuit of knowledge and would have stopped the search if they could. Defiance of our instincts and the resulting upset was the price we had to pay to find understanding.

The great paradox of the human condition was encapsulated in Joe Darian’s lyrics to the 1965 song The Impossible Dream, from the play The Man of La Mancha, in which he wrote that we had to be prepared ‘to march into hell for a heavenly cause’. We had to lose ourselves to find ourselves. Upset was the price of our heroic search for knowledge. In Greek mythology Prometheus stole fire from the Gods and gave it to humans for their use, an act that enraged the Gods, and the God Zeus in particular because he saw that it heralded an era of enlightenment for humans. As punishment Zeus had Prometheus strapped to the top of a mountain where he was forced to suffer having his innards eaten out. We can understand that in this story fire is the metaphor for the conscious intellect and the consequences of humans having it was terrible upset which explains the real reason why Prometheus deserved to be punished by the Gods: he was responsible for humans’ corruption, for their falling out with the Godly ideals. Samuel Taylor Coleridge recognised the suffering that came with our conscious search for understanding, ultimately self-understanding, understanding of our corrupted human condition, when he wrote of becoming a ‘sadder and a wiser man [people]’ (The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, 1797) as a result of our journey.

The origin of so-called ‘sin’ has finally been explained and in the process the fearfully depressing so-called ‘burden of guilt’ has been lifted from the human race forever. And it is science that has made this possible because, after centuries of discovery, science is now able to reveal that while the gene-based learning system can give species orientations only the nerve-based learning system is capable of insightful reasoning, and therein lies the explanation of the human condition.

Page 32 of

PDF Version Most importantly, finding the understanding of the fundamental goodness of humans ends the unjust criticism that has so upset us. Our anger, egocentricity and alienation can now subside. To draw on the analogy once more, our conscious bird Adam Stork would not have become upset if he could have explained why he was not bad to fly off course. It is explanation that is key: understanding is the basis for compassion.

The real need on Earth has been to find the means to love the dark side of ourselves, to bring understanding to that aspect of our make-up. As psychoanalyst Carl Jung emphasised, ‘wholeness’ for humans depended on the ability to ‘own their own shadow’—or as philosopher Laurens van der Post said, ‘True love is love of the difficult and unlovable’ (Journey Into Russia, 1964, p.145). Real compassion is ultimately the only means by which peace and love can come to our planet and it can only be achieved through understanding. It is appropriate to re-include here this earlier quote from van der Post: ‘Compassion leaves an indelible blueprint of the recognition that life so sorely needs between one individual and another; one nation and another; one culture and another. It is also valid for the road which our spirit should be building now for crossing the historical abyss that still separates us from a truly contemporary vision of life, and the increase of life and meaning that awaits us in the future.’ This ‘future’ that van der Post could see, and Berdyaev anticipated, of finding understanding of our human condition has now, thanks to the discoveries of science, finally arrived.

Now that we humans can explain and understand that we are fundamentally good and not bad after all, the insecure, horrifically depressing state of our apparently contradictory nature—our human condition—is reconciled and can thus be ameliorated and brought to an end. As the euphemisms assert, ‘understanding is compassion’, ‘the truth will set you free’ (The Bible, John 8:32) (Note, all biblical references are taken from the 1978 New International Version translation of the Bible), ‘honesty is therapy’ and ‘in repentance lies salvation’—but humans have never before been able to ‘understand’ themselves, know ‘the truth’ about themselves, be ‘honest’ about their condition, explain why they have been upset and in so doing end their insecurity and redeem themselves from upset with honesty.

Humans’ divisive nature is not the unchangeable or immutable state as many people have come to believe, rather it is the result of the human condition, the inability to understand ourselves, and therefore it disappears when that understanding is found—as it now is.

Importantly this understanding of why we became upset as a species doesn’t condone or sanction ‘evil’, rather, through bringing understanding to humans’ upset behaviour, it ameliorates and thus subsides and ultimately eliminates it. With our ego or sense of self-worth satisfied at the most fundamental level our anger can cool and all our denials and resulting alienation can be dismantled. From having lived in a dark cave-like depressed state of condemnation and resulting repressed, hidden state of denial of our true selves, we can now at last, as the song from that immensely optimistic 1960s rock musical Hair says, ‘Let the sunshine in’ (Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In lyrics by James Rado & Gerome Ragni). The psychological rehabilitation of humanity can begin.

At this point it should be emphasised that while the arrival of the dignifying and thus liberating biological understanding of our human condition is the ultimate breakthrough in the human journey to enlightenment—in fact it is the Holy Grail of the whole Darwinian revolution—and our rehabilitation from our upset state can at last begin, there remains one extremely difficult hurdle to be overcome before we are actually free of our upset condition. That hurdle is the difficulty of having to face the truth about ourselves. While our upset state is at last defended we have lived with so much denial of it that the exposure to the truth about ourselves that the breakthrough understanding brings will, for virtually all humans, be overwhelming. The main subject of this book is in fact how we are to cope Page 33 of

PDF Version with the naked truth about ourselves. As has already been mentioned, there is a way and it’s not difficult, in fact it’s an extremely effective, exciting and satisfying way of coping.