The Great Exodus

Page 150 of

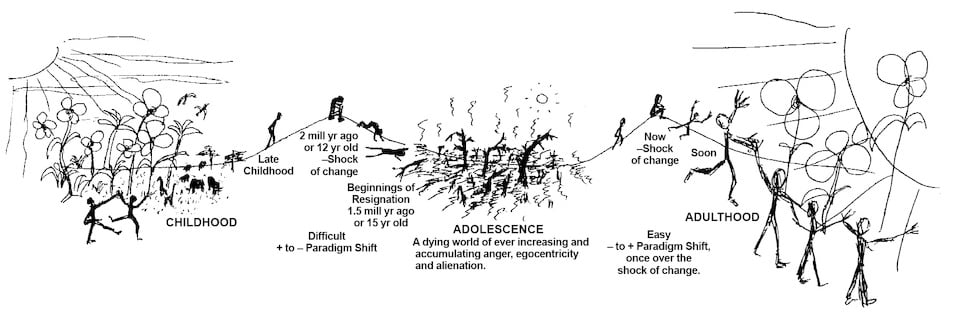

PDF Version 37. The Depressed Adolescent Stage of Adolescent Humanity

This is our Depressed Adolescentman stage, the time when we struggle with the depression that confronting the human condition causes and if necessary resign to living in denial of the issue of the human condition.

The species: the second half of Homo habilis’ reign—2 to 1.5 million years ago

The individual: 14 to 21 years old

Page 151 of

PDF Version By the age of 14 the desperate search for understanding of reality shifts from worrying about the ‘wrongness’ of the whole world to worrying about the horror of the adolescent’s own corrupted condition. The adolescent increasingly realises that the problem of the human condition exists within as well as without. The emerging anger, egocentricity and alienation from the child’s efforts to self-manage raises a serious philosophical question for the now deeply thinking, integrative-meaning-aware adolescent of how to justify that divisive behaviour. Further, children growing up in an already upset world carry the legacy of a love-deficient infancy and early childhood, and thus have the added soul-damaged, hurt, defensive angry divisive behaviours from that legacy to have to mentally, philosophically try to explain and justify. While looking at the wrongness of the world was distressing and depressing enough, confronting your own imperfection without the ability to understand it was unbearably depressing. In fact trying to hold onto the truth of cooperative ideality when you couldn’t explain and understand why the world and you were not ideal was an impossibility. The only solution was to block the whole issue of the human condition from your mind, resign yourself to a life of living in denial of the human condition and any truths and issues—in particular the truth of integrative meaning—that brought that terrifying issue into focus.

While resignation to a life of denial of the human condition was the only option, adolescents did try to resist it because it involved paying an extremely high price. Firstly, to block out the truth of integrative meaning and so many other truths meant that you were never going to be able to think truthfully and thus effectively again. As was emphasised in Section 25, living in denial, especially of the fundamental truth of integrative meaning, meant all your thinking was coming off a false base and was therefore effectively derailed from the outset from making sense of experience. Secondly, it meant blocking out and thus alienating yourself from the whole world of your beautiful, all-sensitive integratively orientated instinctive self or soul because to stay connected with it meant confronting the truth of integrative meaning which was far too hurtful. Aware that they were going to have to pay the price of becoming in effect dead in both intellect and soul, 15 year old adolescents resisted mightily having to resign to a life of denial however the near suicidal depression from trying to face down the issue of the human condition eventually forced them to adopt resignation.

Resignation has been the most important psychological event in a human’s life and yet it has never been able to be admitted until now because to admit it meant admitting that you were living in denial which would defeat the whole purpose of denial. Depression was the main feature of resignation and in fact the main feature of all of human life during our species’ 2 million years of adolescence, as has been its effects, namely the adoption of denial and thus a life in alienation. This book is witness to how much alienation has dominated all aspects of human life, including and in particular science. Not only has the resigned adult world not acknowledged the occurrence of resignation, the moment the adolescent resigns he or she determines never to revisit that terrifying situation again—to such an extent that only a few weeks after resignation adolescents typically find it difficult to recall the event. Evidence of the occurrence of resignation was that glandular fever commonly accompanied it, and many people can remember having had glandular fever in mid-adolescence. In fact glandular fever occurred so commonly at that time it was called ‘the kissing disease’ because puberty, with its first sexual encounters, occurred at the same time as resignation. In fact, just as the ‘terrible twos’ were blamed on teething by denial-committed adults, so glandular fever was blamed on puberty, referring to it as the ‘puberty blues’. The truth is for glandular fever to occur a person’s immune system has to be extremely rundown, yet at puberty the body is physically at its healthiest. Therefore Page 152 of

PDF Version for glandular fever to break out, adolescents must be under extraordinary psychological stress, much greater than the stresses that could possibly be associated with the physical adjustments to puberty. The stresses that cause glandular fever in young adolescents are those associated with having to resign.

While adolescents who have resigned can’t recall what has occurred, those who are still wrestling with having to resign do often write poetry expressing what they are going through. The following is an example of a resignation poem. It was sent to me in February 2000 by the then 27 year old Fiona Miller just after she had read Beyond. To accompany the poem Fiona had attached this comment that recognises how after resignation adolescents find it hard to recall the reasons for the state they were in at the time: ‘I dug out this poem I wrote in my diary when I was about 13 or 14 years old…It has always sounded very depressing to me whenever I have read it and so I have not shown anyone since leaving school…Maybe this was the “transition point” [you write about] for me when instead of trying to fight forever I just integrated very nicely!!??’ Fiona’s amazing poem, included here, reveals the full extent of the sacrifice adolescents make when they resign: ‘You will never have a home again / You’ll forget the bonds of family and family will become just family / Smiles will never bloom from your heart again, but be fake and you will speak fake words to fake people from your fake soul / What you do today you will do tomorrow and what you do tomorrow you will do for the rest of your life / From now on pressure, stress, pain and the past can never be forgotten / You have no heart or soul and there are no good memories / Your mind and thoughts rule your body that will hold all things inside it; bottled up, now impossible to be released / You are fake, you will be fake, you will be a supreme actor of happiness but never be happy / Time, joy and freedom will hardly come your way and never last as you well know / Others’ lives and the dreams of things that you can never have or be part of, will keep you alive / You will become like the rest of the world—a divine actor, trying to hide and suppress your fate, pretending it doesn’t exist / There is only one way to escape society and the world you help build, but that is impossible, for no one can ever become a baby again / Instead you spend the rest of life trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze.’

Being resigned themselves, and thus unable to allow themselves to look at the human condition, or even admit its existence, all parents or adult friends could do was offer sympathy to the resigning adolescent. Mothers could stroke their son’s or daughter’s brow but they couldn’t acknowledge or in any way talk about the struggle that their child was going through. Dying in intellect and soul, so you could live in the upset world, has been an inescapable horror for humans for at least the latter part of humanity’s 2 million years in adolescence.

In The Moral Intelligence of Children, Pulitzer prize-winning author Robert Coles provides a rare, remarkably honest description of the agony of resignation and the difficulty adults have had in helping adolescents during this period. He wrote: ‘I tell of the loneliness many young people feel, even if they have a good number of friends…It’s a loneliness that has to do with a self-imposed judgment of sorts: I am pushed and pulled by an array of urges, yearnings, worries, fears, that I can’t share with anyone, really…This sense of utter difference…makes for a certain moodiness well known among adolescents, who are, after all, constantly trying to figure out exactly how they ought to and might live…I remember…a young man of fifteen who engaged in light banter, only to shut down, shake his head, refuse to talk at all when his own life and troubles became the subject at hand. He had stopped going to school, begun using large amounts of pot; he sat in his room for hours listening to rock music, the door closed. To myself I called him a host of psychiatric names: withdrawn, depressed, possibly psychotic; finally I asked him about his head-shaking behavior: I wondered whom he was thereby addressing. He replied: “No one.” I hesitated, gulped a bit as I took a chance: “Not yourself?” He looked right at me now in a sustained stare, for the first time. “Why do you say that?”…I decided not to answer the question in the manner that I was Page 153 of

PDF Version trained to reply…an account of what I had surmised about him, what I thought was happening inside him…Instead, with some unease…I heard myself saying this: “I’ve been there; I remember being there—remember when I felt I couldn’t say a word to anyone”…I can still remember those words, still remember feeling that I ought not have spoken them: it was a breach in “technique.” The young man kept staring at me, didn’t speak, at least with his mouth. When he took out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes, I realized they had begun to fill’ (1996, pp.143—144 of 218). When Coles says that ‘I heard myself saying this: I’ve been there; I remember being there’, and that his acknowledgment was ‘a breach in technique’, he is admitting that resignation has been something so dark humans have had to forget it. The phrase ‘I’ve been there’ was also used by the Australian poet Henry Lawson in his 1897 poem The Voice from Over Yonder which is about the depression associated with trying to confront the issue of the human condition: ‘“Say it! think it, if you dare! / Have you ever thought or wondered / Why the Man and God were sundered? / Do you think the Maker blundered?” / And the voice in mocking accents, answered only: “I’ve been there.”’ The unsaid words in this final phrase are, ‘and I’m not going there again’; the ‘there’ and the ‘over yonder’ of the title being the state of depression.

Educators are well aware of the time in young people’s lives when they fall away in mid-adolescence. For example education reporter Luis M. Garcia wrote, ‘It is known as the “turn-off” syndrome, and it is the sort of problem most teachers and many parents know only too well. Bright and promising students who seem to have the world at their feet, turn 13 or 14 and stop dead in their tracks. They lose interest in schoolwork and start to fail examinations. Many cannot wait until they reach 15 so they can drop out’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1985). We are able to understand why, as mentioned earlier, ‘Teachers consider years nine and ten, when students are 14, 15 and 16 years old, the most difficult to teach. The adolescents seem to be at complete odds with what is expected of them. Most teachers are terrified of these completely uncooperative mid-teenage ages’. The Australian playwright Richard Tulloch even wrote a popular play about 14 and 15 year olds titled Year 9 Are Animals (1987).

The question is how exactly is denial of the human condition achieved? Essentially it involves two actions. Firstly you have to deny the existence of ideality. If there is no ideal state then there is no dilemma, no issue with not being ideal. However, it is not sufficient to merely deny the existence of cooperative, integrative ideality, it is also necessary to believe that selfish, aggressive competitiveness is a valid, meaningful way of behaving. Essentially, to deny the issue of the human condition the mind has to make an amazing switch from believing in cooperative, integrative ideality to believing in false excuses for humans’ upset, divisive behaviour. We need to look at what happens at the actual moment of resignation. Thinking increasingly deeply about the issue of their own lack of ideality, the adolescent eventually reaches a moment of perfect clarity on the matter where, on one hand, they can see perfectly clearly the truth of cooperative ideality, and, on the other hand, just how corrupted or non-ideal they are. At this moment they are thinking entirely truthfully and profoundly, delving right to the bottom of the dilemma of their condition and seeing the full implication of their apparent worthlessness. It is at this point that depression reaches its peak; in fact the depression at this moment is incredibly intense, as though their whole body is going to dissolve, disintegrate with agony and pain, and it is at this point that the adolescent becomes receptive to the option of adopting denial of the issue of the human condition, incredibly false as they know it to be. In fact he or she does not just welcome the lies they are going to have to adopt, they embrace them as if embracing their mother; such is their fear of revisiting the depression they have just experienced. The negatives of becoming a false person have no currency at that moment when the need for relief is so desperate. Once the mind resigns itself to blocking out the truth of cooperative, integrative meaning and becomes determined to Page 154 of

PDF Version believe that competitiveness is meaningful, it doesn’t take long to find contrived excuses for competitiveness. The mind sees that ‘virtually everyone else is behaving selfishly and competitively, so such behaviour must simply be human nature, an entirely permissible, natural way to behave’, and ‘humans are only animals and animals are always competing with, fighting and killing each other, so that’s why we humans are’. The journey of finding contrived excuses for our human condition that were described in Section 16 is underway.

From the moment of resignation onwards, maintaining the denial becomes a minute by minute growing preoccupation, until, as pointed out, after only a few days, recalling the truth of cooperative ideality and the question it raises of their corrupted condition becomes a forgotten issue. The resigned adolescent determines that the terrible ‘dark night of the soul’, as resignation has been aptly described—that awful moment when the issue of the human condition was seen starkly, will never occur again. Once the escape route is accepted, going back to confrontation with the human condition becomes an anathema—which is why it is initially so hard for people who are resigned to take in or ‘hear’ any of the analysis of the human condition in my books. It is a realm that resigned minds are absolutely determined never to allow themselves to go near again. Even though it has now at last become safe to confront the issue of the human condition because we have found understanding of it, resigned adults have such an extreme fear of the subject it is hard for their mind to reconsider their original resigned stand of never looking at the subject again. Christ was an unresigned, unevasive, denial-free thinker and he described the problem perfectly when he said, ‘why is my language not clear to you? Because you are unable to hear what I say…The reason you do not hear is that you do not belong to God [you live in denial of integrative meaning and the issue of the human condition it raises]’ (John 8:43-47).

After only a few days it is almost impossible for people who have become resigned to consider there is such a thing as a cooperative purpose to existence, or to consider humans were once instinctively orientated to living cooperatively. Resigned minds believe with a passion that humans were once brutish and aggressive ‘like other animals’. They will not allow themselves to believe that humans have an instinctive self or soul orientated to cooperative behaviour. And they believe with all their being that there is no such thing as integrative meaning and that the meaning of life is to be competitive, and that succeeding in competition with other humans is the way to achieve a secure sense of self-worth. They actually believe, and live out their belief, that ‘winning is everything’, that success in the form of power, fame, fortune and glory is meaningful. And it does sustain them, not because competition and winning is meaningful, but because it keeps their mind from the few steps of logic it would take to bring them back into contact with the depressing issue of the human condition. Their mind in effect says ‘I am going to believe in, live off, and enjoy this new way of viewing the world; I simply do not care if it is false’.

So this is how humans have made the absolutely amazing switch from being totally aware of and believing in a moral, cooperative, selfless, loving world, to believing in a competitive, selfish, aggressive, egocentric, must-win, power-fame-fortune-and-glory-obsessed existence. Of course the other aspect of the commitment to denial and evasion of the issue of the human condition is the extreme need for self-distraction and artificial forms of self-glorification which materialism services.

It needs to be emphasised that with understanding of the human condition now found, adolescents will no longer have to endure the horror of resignation. Not having to resign to a life of alienation and burial of the magic world of their soul, they will stay alive inside and be like a new variety of beings on Earth. Also, with understanding available of why we have been the way we have been, namely massively corrupted, that greatest of living Page 155 of

PDF Version horrors of depression will disappear from Earth—and people say to me ‘why do you persevere writing books about the human condition?’

For a full account of resignation read the ‘Resignation’ chapter in A Species In Denial which is available online at <www.worldtransformation.com/asid>.

In the case of humanity’s journey, the time when resignation became the feature of most adult lives would not have occurred in the lives of H. habilis, or even in the lives of the H. erectus representatives of the next adventurous early adulthood stage. This is because it is the upset from the lack of nurturing in infancy and early childhood that makes self-confrontation during the thoughtful early adolescent stage overwhelmingly depressing, and this lack of nurturing was not a feature of human life until the latter stages of humanity’s adolescence. The upset from a developing mind’s own efforts to self-adjust, while distressing and even depressing are not sufficient to cause the mind to have to block out the truth of cooperative ideality. Evidence for this is that even amongst the H. sapiens sapiens 40 year old plus equivalent varieties of humans living today there are adults who haven’t resigned. As has been explained earlier in this book, truthful, effective thinking prophets have to be unresigned individuals and while rare, there have always been some such individuals in society. Also quite a number of adults in relatively innocent representative races of H. sapiens sapiens, such as the Bushmen of the Kalahari, must not be resigned to be as happy and full of the zest and enthusiasm for life and as generous, selfless and free in spirit as numbers of them are, or at least were when they were still living as hunter gatherers. R.D. Laing summed up the situation that exists even today when he said, ‘Each child is a new beginning, a potential prophet’. With sufficient nurturing any human today is capable of remaining sufficiently innocent or free of upset to not have to resign to a life of living in denial of the issue of the human condition and, by not having resigned, be an honest, denial-free thinking adult—or what we historically refer to as a prophet. The human race is not so instinctively adapted to upset now that humans are no longer capable of being innocent enough to avoid resignation. The reality is that to have to live in such deep denial that the whole issue of the human condition becomes unacknowledgeable requires a great deal of hurt to have to confront. Bruce Chatwin acknowledged that ‘First man’ was an unresigned, denial-free thinking prophet like Christ when, in his 1989 book What Am I Doing Here?, he said ‘There is no contradiction between the Theory of Evolution and belief in God and His Son on earth. If Christ were the perfect instinctual specimen—and we have every reason to believe He was—He must be the Son of God. By the same token the First man was also Christ’ (p.65 of 367). We can expect that resignation has only become almost universal amongst adult humans since the advent of agriculture and the domestication of animals which allowed humans to live in close proximity, the effect of which was to rapidly spread and compound upset behaviour. The effect of the rapid increase in upset that came with the more sedentary and close-living existence that agriculture and the domestication of animals made possible will be referred to again shortly in this book and is described in more detail in the ‘Denial-Free History of the Human Race’ chapter in A Species In Denial. Even in the early days of Athens there must have been quite a number of unresigned, denial-free effective thinking prophets for that society to have been so extraordinarily innovative, laying down as it did in that ‘Golden Age’ so many of the foundation ideas for the western world, across politics, philosophy, science, psychology, astronomy, architecture and art. Certainly the early Athenians Socrates and Plato were prophets. Very early Athenian society must especially have been composed of relatively innocent people because they were sufficiently ego-free to seek out and tolerate having uncorrupted, innocent shepherds run Athens. Indeed the prophet Mohammed observed ‘that every prophet was a shepherd in his youth’ (Eastern Definitions, Edward Page 156 of

PDF Version Rice, 1978, p.260 of 433). Laurens van der Post noted that in the turbulent period of Plato’s time Pericles, a close friend of Plato’s stepfather, ‘urged the Athenians therefore to go back to their ancient rule of choosing men who lived on and off the land and were reluctant to spend their lives in towns, and prepared to serve them purely out of sense of public duty and not like their present rulers who did so uniquely for personal power and advancement’ (Foreword to Progress Without Loss of Soul, by Theodor Abt, 1983, p.xii of 389). It is the unnatural world of city living that is especially distressing to our original instinctive self or soul.

We now need to look at what happened in the years immediately following resignation, and also what happened in those same years from 15 to 21 years of age for humans who didn’t have to resign, in particular for our forebears who were members of the second half of H. habilis’ reign.

While adolescents who had to resign to living a life of denial did so at about the age of 15, it normally took them another six years of procrastination before they had made sufficient mental adjustments to embrace the extremely dishonest resigned way of living. It was not until they reached 21 that they finally managed to orientate themselves to living such a compromised life. There were two main adjustments the resigned adolescent had to make: firstly they had to block out the negative that living so falsely and thus so dead in soul and intellect had to eventually end in the disaster of a completely corrupted life; and secondly, they had to train their mind to block out all memory of their innocent childhood and focus on whatever meagre positives they could find in the journey ahead.

Even for those who hadn’t become so upset that they had to resign to a life of living in denial of the issue of the human condition, their lives followed a parallel path to the resigned path. While they hadn’t become so upset that cooperative ideality was unbearably depressing, they were accumulating upset angry, egocentric and alienated behaviour at a rapid rate and were thus increasingly having to cope with the distress of not being ideally behaved. Throughout humanity’s adolescence we can work out that upset was accumulating and therefore that the need for relief from the guilt of that condition would have also been increasing. The need for resignation to a life of total denial and with it a totally false and deluded existence would occur at a certain point in the escalation of guilt but up to that point there would still be ever-increasing worry and insecurity about being divisively behaved and having to live in an upset world. Resignation simply means a switch to a totally evasive, dishonest and deluded existence. Basically resignation means the mind stops worrying and decides to block the whole issue of the human condition out and live in a totally fabricated, artificial world. Resignation is essentially a form of autism—the behaviour matches perfectly the description Winnicott gave earlier for the behaviour associated with autism: ‘Autism is a highly sophisticated defence organization. What we see is invulnerability…The child carries round the (lost) memory of unthinkable anxiety, and the illness is a complex mental structure insuring against recurrence of the conditions of the unthinkable anxiety.’ Someone who is upset but not resigned is still living with the worry of their and the upset human race’s imperfection whereas someone who has become resigned is living preoccupied with making sure they don’t allow their mind to confront the issue of the human condition, the issue of their imperfection. The unresigned need relief and distraction from their worrying about the human condition and the resigned need relief and distraction to maintain their denial of the human condition, so they both need relief and distraction even though their reasons are different. As the journey of ever-increasing upset progressed eventually, towards the very end of that horrible 2 million years’ journey, only the consumption of drugs and alcohol and partying long into the night could relieve the adolescent’s agony of having to accept life under the duress of the human condition.Page 157 of

PDF Version

Drawing by Jeremy Griffith © 1996 Fedmex Pty Ltd

The period of procrastinating about taking up adulthood that took place from 15 to 21 years of age in the case of the individual, or during the second half of H. habilis’ reign in the case of humanity, can be visualised as standing on a ridge between two valleys. Behind us lay the valley of our enchanted childhood, the ‘Garden of Eden’ where we all lived happily, extremely sensitively in a non-upset, cooperative state. Before us lay a hell of smouldering wasteland of devastation and destruction, the wilderness of terrible upset and alienation. Of course we did not want to go forward into that wasteland but retreat was also impossible. How could we leave all that happiness, laughter and togetherness behind, but turn our back on it we had to. We couldn’t throw away our conscious mind. We couldn’t stop thinking and while we practiced thinking upset was an inescapable by-product that could only be ameliorated by finding understanding of our corrupted state—and that understanding lay at the other side of that terrible wilderness of devastation, aloneness and alienation.

Fiona Miller described very clearly the consequences of resignation in her resignation poem: ‘Smiles will never bloom from your heart again, but be fake and you will speak fake words to fake people from your fake soul…From now on pressure, stress, pain and the past can never be forgotten / You have no heart or soul and there are no good memories…You are fake, you will be fake, you will be a supreme actor of happiness but never be happy…You will become like the rest of the world—a divine actor, trying to hide and suppress your fate, pretending it doesn’t exist / There is only one way to escape society and the world you help build, but that is impossible, for no one can ever become a baby again / Instead you spend the rest of life trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze.’

For a long time we sat on that ridge procrastinating, trying to resist the inevitable. Gradually we taught ourselves to avoid looking back at our lost, happy innocent world because looking at it only made the journey before us impossible. Instead of looking back we forced ourselves to focus ahead and try and find something in that wasteland that would bring us some happiness to make the unavoidable journey through it bearable. There were only two tiny positives that existed in that journey ahead. These positives were ‘tiny’ because the happiness humans could derive from them was in truth no comparison to the happiness we had while we were living in the magic state of our soul’s true world.

The first tiny positive was that at least there was the adventure to look forward to of trying to avoid the inevitable disaster of complete self-corruption as much, and for as long as possible. We may be going to ‘go under’—become totally corrupted—but at least we could hope to make a good fight of it. In fact, as will be described in the next 21-year-old-plus stage, by the age of 21, young resigned adult men in particular could have so blocked Page 158 of

PDF Version out the fact they had resigned and resignation’s corrupting consequences that they could delude themselves that they might even be able to win their resigned egocentric struggle to prove their worth through winning power, fame, fortune and glory. The second, in truth tiny, positive in the resigned existence was romance, the hope of ‘falling in love’, which can be now understood as the hope of escaping reality through the dream of ideality that could be inspired by the neotenous image of innocence in women. Men could dream that women were actually innocent and that they could share in that innocent state. For their part, women could use the fact that men were inspired by their image of innocence to delude themselves that they were actually innocent. As was explained in Section 22, sex became used as an expression of this dream of being ‘in love’.

Although these two positives were only tiny, resigned adolescents gradually built them up in their mind so they appeared as big positives. They had to mentally posture themselves in such a way as to be able to leave that ridge and take up that journey to find the greater liberating understanding of their upset, corrupted condition. There is a very famous story that describes exactly the journey they had to undertake. Its origins are said to be from the Hottentot indigenous peoples of Southern Africa. In this story the search for the greater liberating understanding is described as the bird of truth. Instead of a valley of wasteland that had to be crossed to reach the liberating truth this story talks of a mountain that had to be climbed. Each generation cut another step up that mountain. Laurens van der Post often refers to this story in his famous books about the Kalahari Bushmen people, a people closely related to the Hottentots; in fact his 1994 book is titled Feather Fall in recognition of this famous story in which each generation, in cutting its step in the accumulation of knowledge, is rewarded with its feather of enlightenment towards that final enlightenment of the human condition humanity sought.

Olive Schreiner presents a version of the story in her 1883 book, The Story of an African Farm. The passage is eleven pages long so I will only include the very beginning and the very end: ‘In certain valleys there was a hunter…Day by day he went to hunt for wild-fowl in the woods; and it chanced that once he stood on the shores of a large lake. While he stood waiting in the rushes for the coming of the birds, a great shadow fell on him, and in the water he saw a reflection. He looked up to the sky; but the thing was gone. Then a burning desire came over him to see once again that reflection in the water, and all day he watched and waited; but night came, and it had not returned. Then he went home with his empty bag, moody and silent. His comrades came questioning about him to know the reason, but he answered them nothing; he sat alone and brooded. Then his friend came to him, and to him he spoke. “I have seen today,” he said, “that which I never saw before—a vast white bird, with silver wings outstretched, sailing in the everlasting blue. And now it is as though a great fire burnt within my breast. It was but a sheen, a shimmer, a reflection in the water; but now I desire nothing more on earth than to hold her.” His friend laughed. “It was but a beam playing on the water, or the shadow of your own head. Tomorrow you will forget her,” he said. But tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow the hunter walked alone. He sought in the forest and in the woods, by the lakes and among the rushes, but he could not find her. He shot no more wild-fowl; what were they to him? “What ails him?” said his comrades. “He is mad,” said one. “No; but he is worse,” said another; “he would see that which none of us have seen, and make himself a wonder.” “Come, let us forswear his company,” said all. So the hunter walked alone. One night, as he wandered in the shade, very heart-sore and weeping, an old man stood before him, grander and taller than the sons of men. “Who are you?” asked the hunter. “I am Wisdom,” answered the old man; “but some men called me Knowledge. All my life I have grown in these valleys; but no man sees me till he has Page 159 of

PDF Version sorrowed much. The eyes must be washed with tears that are to behold me; and, according as a man has suffered, I speak.” And the hunter cried: “Oh, you who have lived here so long, tell me, what is that great wild bird I have seen sailing in the blue? They would have me believe she is a dream; the shadow of my own head.” The old man smiled. “Her name is Truth. He who has once seen her never rests again. Till death he desires her.” And the hunter cried: “Oh, tell me where I may find her.” But the man said: “You have not suffered enough,” and went. Then the hunter took from his breast the shuttle of Imagination, and wound on it the thread of his Wishes and all night he sat and wove a net” (pp.159—161 of 301).

In this net the hunter catches these particular birds: ‘A human-God’, ‘Immortality’ and ‘Reward after Death’, but these proved to be a ‘brood of Lies’. He then goes down the valley of ‘Absolute Negation and Denial’ to the mountain of the Truth where Wisdom tells him if enough white, silver feathers from the wing of Truth are gathered by men and woven into a cord for a net then that net can capture Truth. Wisdom says ‘Nothing but Truth can hold Truth’ (author’s emphasis). He is told after leaving the valley he can never return even though he should weep tears of blood to try and return: ‘Who goes; goes freely—for the great love that is in him. The work is his reward’. On setting out ‘the child of The-Accumulated-Knowledge-of-Ages’ joins him but the child can only walk where many men have trodden. On the way he is tempted by ‘the twins Sensuality’, whose father is ‘Human-Nature’ and whose mother is ‘Excess’. He then goes through ‘Dry-facts’, ‘Realities’ and ‘False Hopes’ till he can look back over the ‘valley of superstition’. Finally he climbs up the mountain of Truth until the path ends at a wall of rock into which he starts cutting steps: ‘And the years rolled on: he counted them by the steps he had cut—a few for each year—only a few. He sang no more; he said no more, “I will do this or that”—he only worked. And at night, when the twilight settled down, there looked out at him from the holes and crevices in the rocks strange wild faces. “Stop your work, you lonely man, and speak to us,” they cried. “My salvation is in work. If I should stop but for one moment you would creep down upon me,” he replied. And they put out their long necks further. “Look down into the crevice at your feet,” they said. “See what lie there—white bones! As brave and strong a man as you climbed to these rocks. And he looked up. He saw there was no use in striving; he would never hold Truth, never see her, never find her. So he lay down here, for he was very tired. He went to sleep for ever. He put himself to sleep. Sleep is very tranquil. You are not lonely when you are asleep, neither do your hands ache, nor your heart.” And the hunter laughed between his teeth. “Have I torn from my heart all that was dearest; have I wandered alone in the land of night; have I resisted temptation; have I dwelt where the voice of my kind is never heard, and laboured alone, to lie down and be food for you, ye harpies?” He laughed fiercely; and the Echoes of Despair slunk away, for the laugh of a brave, strong heart is as a death-blow to them. Nevertheless they crept out again and looked at him. “Do you know that your hair is white?” they said, “that your hands begin to tremble like a child’s? Do you see that the point of your shuttle is gone?—it is cracked already. If you should ever climb this stair,” they said, “it will be your last. You will never climb another.” And he answered, “I know it!” and worked on. The old, thin hands cut the stones ill and jaggedly for the fingers were stiff and bent. The beauty and the strength of the man was gone. At last, an old, wizened, shrunken face looked out above the rocks. It saw the eternal mountains rise with walls to the white clouds; but its work was done. The old hunter folded his tired hands and lay down by the precipice where he had worked away his life. It was the sleeping time at last. Below him over the valleys rolled the thick white mist. Once it broke; and through the gap the dying eyes looked down on the trees and fields of their childhood. From afar seemed borne to him the cry of his own wild birds, and he heard the noise of people singing as they danced. And he thought he heard among Page 160 of

PDF Version them the voices of his old comrades; and he saw far off the sunlight shine on his early home. And great tears gathered in the hunter’s eyes. “Ah! they who die there do not die alone,” he cried. Then the mists rolled together again; and he turned his eyes away. “I have sought,” he said, “for long years I have laboured; but I have not found her. I have not rested, I have not repined, and I have not seen her; now my strength is gone. Where I lie down worn out other men will stand, young and fresh. By the steps that I have cut they will climb; by the stairs that I have built they will mount. They will never know the name of the man who made them. At the clumsy work they will laugh; when the stones roll they will curse me. But they will mount, and on my work; they will climb, and by my stair! They will find her, and through me! And no man liveth to himself, and no man dieth to himself.” The tears rolled from beneath the shrivelled eyelids. If Truth had appeared above him in the clouds now he could not have seen her, the mist of death was in his eyes. “My soul hears their glad step coming,” he said; “ and they shall mount! they shall mount!” He raised his shrivelled hand to his eyes. Then slowly from the white sky above, through the still air, came something falling, falling, falling. Softly it fluttered down, and dropped on to the breast of the dying man. He felt it with his hands. It was a feather. He died holding it’ (pp.167—169).

While all the deadening escapism, evasion and denial that humans have had to practice throughout humanity’s journey to find liberating understanding of the human condition have been necessary, the process was going to eventually lead to almost complete estrangement or alienation from our soul’s happy, loving and all-sensitive world. Humans would be left as waifs wandering in a terrible wilderness of the darkness of denial and its alienation. The book of Genesis in the Bible contains this accurate description of our species’ unhappy banishment from our original Godly, soulful, Garden of Eden state: ‘Today you are driving me from the land, and I will be hidden from your presence, I will be a restless wanderer on the earth’ (4:14).

The courage of all humans who have lived during humanity’s heroic 2 million years in adolescence where they had to face the inevitable total self-corruption by the end of their lives has been so immense it is something that is, and possibly will be for all time, out of reach of appreciation. Like the story of the feather fall, Joe Darian’s 1965 song, The Impossible Dream, from the play The Man of La Mancha, contains this wonderful description of the courage needed by humans to accept their horrific destiny while they painstakingly contributed their little bit to humanity’s long term goal of finding understanding of the human condition and by so doing achieve the seemingly ‘impossible dream’ of liberating humanity from its paradoxical condition of appearing to be bad when in fact it was good: ‘To dream the impossible dream, to fight the unbeatable foe / To bear the unbearable sorrow, to run where the brave dare not go / To right the unrightable wrong, to love pure and chaste from afar / To try when your arms are too weary, to reach the unreachable star / This is my quest, to follow that star / No matter how hopeless, no matter how far / To fight for the right without question or pause / To be willing to march into hell for a heavenly cause / And I know if I will only be true, to this glorious quest / That my heart will lie peaceful and calm, when I’m laid to my rest / And the world will be better for this, that one man scorned and covered with scars / Still strove with his last ounce of courage, to reach the unreachable star.’