‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 5 The Origin of Humans’ Moral Instinctive Self or Soul

Chapter 5:6 Bonobos provide living evidence of the love-indoctrination process

While these recent fossil discoveries are providing exciting confirmation that our ape ancestors completed the development of the love-indoctrination process, of the living primate species, only Pan paniscus, the bonobos (or pygmy chimpanzees as they were once called because of their comparatively gracile bodies), have not only developed love-indoctrination, they appear to have come close to completing the love-indoctrination process to become a fully integrated Specie Individual; they are certainly by far the most cooperative/harmonious/gentle/loving/integrated of the non-human primates. It follows then that although there is no suggestion that bonobos or chimpanzees are a living human ancestor, comparisons have been made between bonobos and our ancestors. For instance, the physical anthropologist Adrienne Zihlman first proposed in 1978 ‘that, among living species, the pygmy chimpanzee (P. paniscus) offers us the best prototype of the prehominid ancestor’ (Adrienne L. Zihlman et al., ‘Pygmy chimpanzee as a possible prototype for the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas’, Nature, 1978, Vol.275, No.5682), using the then earliest known human ancestor, Australopithecus, to compare the two species’ physical characteristics, including their bipedality, canine teeth and lack of sexual size dimorphism. In 1996 Zihlman refined her assessment to include similarities with the (at the time) newly discovered Ardipithecus. In a further example, the primatologist Frans de Waal has noted the extraordinary similarity between Ardipithecus and the bonobo, saying, ‘The bonobo’s body proportions—its long legs and narrow shoulders—seem to perfectly fit the descriptions of Ardi, as do its relatively small canines’ (The Bonobo and the Atheist, 2013, p.61 of 289). (Note, although the bonobo male ‘possesses smaller canines than any other [male] hominoid [apes and their ancestors]’ (J. Michael Plavcan et al., ‘Competition, coalitions and canine size in primates’, Journal of Human Evolution, 1995, Vol.28, No.3), which, as explained in par. 406 above, is in itself a marker of low levels of aggression between males and thus a sign the love-indoctrination process is well underway in bonobo society, their canines do feature a sharp cutting edge that is absent in Ardipithecus, which suggests competitive fighting hasn’t been completely eliminated within bonobo society and that the process is not as advanced in bonobos as it was in Ardipithecus.) So bonobos (who, along with their chimpanzee cousins, share 98.7 percent of their DNA with humans) are physiologically extremely similar to our fossil ancestors, but beyond the physical similarities, some scientists are suggesting bonobo behaviour also corresponds with that of our ancestors. In addition to the view expressed above by Gen Suwa, that, like bonobos, Ardipithecus were not male dominated, Zihlman has suggested that ‘the Pan paniscus model offers another way to view the social life of early hominids, given their sociability, lack of male dominance and the female-centric features of their society’ (‘Reconstructions reconsidered: chimpanzee models and human evolution’, Great Ape Societies, eds William C. McGrew et al., 1996, p.301 of 352).

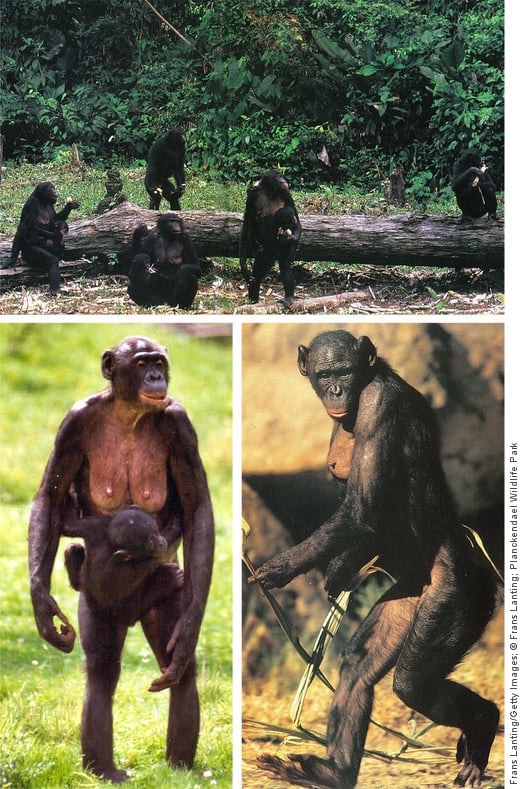

So given the exceptionally cooperatively behaved, matriarchal bonobo species has developed the love-indoctrination process, we should expect that they provide living evidence of the three elements previously identified as being required for that process to occur: bipedalism, ideal nursery conditions, and selection for more maternal mothers.

A bonobo rests in a nest of compacted branches and leaves high in the

forest canopy at the LuiKotale Study Site, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

With her infant beside her, Kame shares provisioned sugar cane with Senta, a non-related

juvenile, at the Wamba bonobo research station, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1987.

In relation to bipedalism, research confirms that bonobos are extremely well-adapted to upright walking; in fact, they are ‘the most bipedal of all the extant [living] apes’ (Roberto Macchiarelli et al., ‘Comparative analysis of the iliac trabecular architecture in extant and fossil primates by means of digital image processing techniques’, Hominoid Evolution and Climate Change in Europe: Vol.2, eds Louis de Bonis et al., 2001, p.71 of 372). As was explained earlier, we can now account for this bipedality, along with bonobos’ peaceful cooperative nature: the longer infancy is delayed, the more and longer infants had to be held, thus the greater need and, therefore, selection for arms-freed, upright walking.

Upright Bonobos. Note the well-developed breasts (similar to those of female humans) for suckling

their young—another indication of how important a role nurturing is playing in bonobo society.

As mentioned, ideal nursery conditions are the second requirement for establishing love-indoctrination—and bonobos have certainly benefited from a comfortable environment in the food-rich, relatively predator-and-competitor-free, ideal nursery conditions of the rainforests south of the Congo River. (Bonobos, for example, don’t have to compete with gorillas, who have a diet similar to that of the bonobo but who live north of the Congo River.) This fortuitous geographic situation is thought to have been created about 2 million years ago after the formation of the Congo River divided an ancestral population of what became, some 1 million years ago, the two distinct species of bonobos and chimpanzees, with the bonobos, Pan paniscus, as mentioned, living south of the river, while the chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes, found themselves confined to areas north and east of the river.

The ideality of these nursery conditions, which have been so conducive to their successful development of the love-indoctrination process, and the resulting love-indoctrinated cooperativeness of the bonobos compared with that of their chimpanzee cousins, is apparent in this quote: ‘we may say that the pygmy chimpanzees historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food. Pygmy chimpanzees appear conservative in their food habits and unlike common chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure and elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior…Prior to the Bantu (Mongo) agriculturists’ invasion into the central Zaire basin, the pygmy chimpanzees may have led a carefree life in a comparatively stable environment’ (Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, ‘Feeding ecology of the pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus)’; The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, p.271 of 435). Indeed, it is an indication of how difficult it is to develop love-indoctrination that even bonobos, living as they do in their ideal conditions, and who ‘have developed a more cohesive social structure’ than chimpanzees, still find it necessary to employ sex as an appeasement device to help subside residual tension and aggression between individuals; this is the ‘elaborate inventory of sociosexual behavior’ referred to in this quote. As Frans de Waal has written, ‘For these animals [bonobos], sexual behavior is indistinguishable from social behavior. Given its peacemaking and appeasement functions, it is not surprising that sex among bonobos occurs in so many different partner combinations, including between juveniles and adults. The need for peaceful coexistence is obviously not restricted to adult heterosexual pairs’ (‘Bonobo Sex and Society’, Scientific American, Mar. 1995). Clearly, sex amongst bonobos is like the ‘naked and they felt no shame’ (Gen. 2:25) sex that Moses described our innocent Adam and Eve/bonobo stage-equivalent ancestors as practising, not the anti-‘social’ sex that humans currently practise, where, as will be explained in chapter 8:11B, it is used to attack/fuck innocence and, as a result, we have become self-consciously ‘shame[ful]’ and had to put on clothes to dampen our destructive lust—as Moses said, we ‘realised that’ we ‘were naked; so’ we ‘made coverings for’ ourselves (Gen. 3:7). Bonobos also use a rich and constant array of vocalisations to assist the developing ‘cohesive social structure’ of the group. Indeed, ‘Bonobos are the most vocal of the great apes’ (‘What is a Bonobo?’, Bonobo Conservation Initiative; see <www.wtmsources.com/119>), and ‘are excitable creatures who frequently “comment” on minor events around them through high-pitched peeps and barks. Even if most of these vocalizations are noticeable only at close range, one definitely hears more vocal exchange in a group of bonobos than in a group of chimpanzees’ (Frans de Waal & Frans Lanting, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, 1997, p.10 of 210). But just how extraordinarily ‘cohesive’ or integrated the bonobo species has become through their development of the love-indoctrination process is apparent in the following quote from the primatologist Barbara Fruth, who has spent many years studying bonobos in their natural habitat: ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, Last Tribes on Earth.com, 2003; see <www.wtmsources.com/143>). So there is relatively little conflict between individual bonobos or even between groups of bonobos, which is another indication that this species is well on its way to integrating its members into the Specie Individual—a feat that all evidence indicates is what our ape ancestors succeeded in achieving.

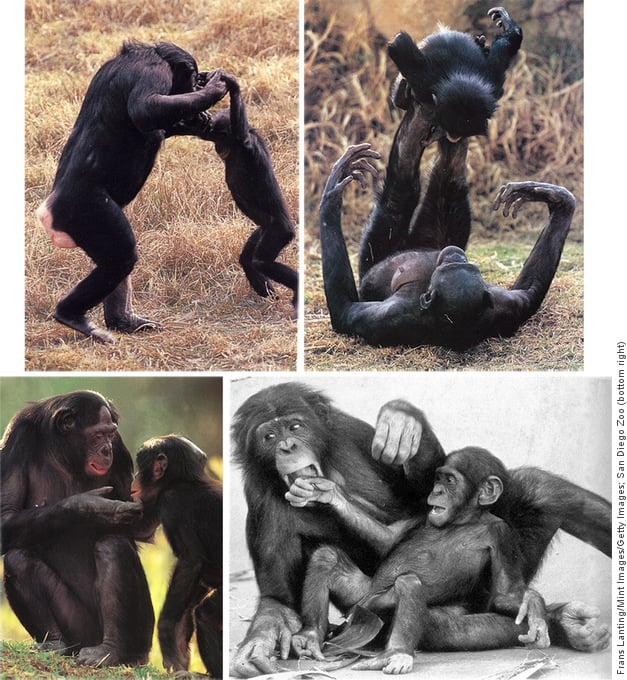

However, while a situation conducive to the development of integration of sufficient food, shelter and territory can be reached, from a genetic point of view there can never usually be enough of that other key resource—mates—simply because the more successfully an individual can breed, the more their genes can carry on and multiply. Since females are limited in how often they can reproduce due to pregnancy—and, in the case of mammals, lactation—it is the males who have the opportunity to breed continuously, and so it is the competition for mating opportunities amongst males that is the most difficult form of genetic selfishness to overcome. Whilst bonobos haven’t been able to fully develop love-indoctrination and thus integration, as evidenced by the fact that they have to use sex to quell residual tension and vocal communication to support their social cohesion, they have been able to develop it sufficiently to bring to an end this most difficult of all forms of selfish competitiveness, male competition for mating opportunities, as the fossil evidence now suggests our ape ancestors did. (With sex engaged in so frequently, males who generate more sperm will be more likely to reproduce, and so bonobos have developed relatively large testes; however, this ‘sperm competition’ is not evidence that males are actively competing for mating opportunities, it just indicates the strength of the underlying genetic imperative. The genes are still trying to find a way to ensure their reproduction even though the love-indoctrination process has overcome the competitive behaviour amongst males.) In fact, bonobos have been so successful at reining in male competition for mating opportunities that within their society there has been what could be described as a gender-role reversal, with bonobo females forming alliances and dominating social groups, both of which are distinctly male behaviours in chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and other non-human primate societies. Bonobo society is matriarchal, female-dominated, controlled and led. Further, in bonobo society, the entire focus of the social group does appear to be on the maternal, or female, role of nurturing infants, as this observation by America’s leading ape-language researcher, the biologist and psychologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh evidences: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among common chimps, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong…Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group’ (Sue Savage-Rumbaugh & writer Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, 1994, p.108 of 299). It is just such circumstances one would expect in a society that exhibits the third element necessary for love-indoctrination, selection for more maternal mothers.

The following photographs of bonobos with infants reveal something of just how exceptionally nurturing bonobo females are—and even males, because the bottom right photo is of a male lovingly playing with an infant. Bonobos have clearly had the environmental comfort and the freedom from fighting and tension in their world needed to develop the ability to love their infants.

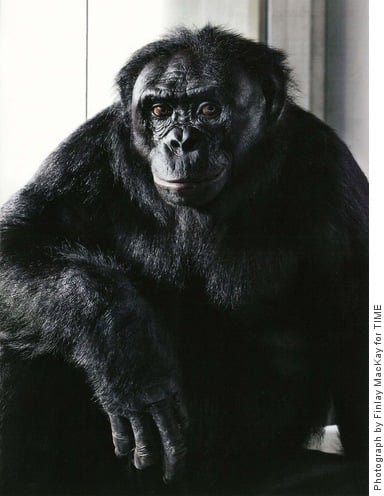

The 2011 French documentary Bonobos, which was directed by Alain Tixier, contains marvellous footage evidencing the ability of bonobos to nurture their infants and the wondrous effect such nurturing has on their offspring. A short segment from the documentary showing the tenderness of the bonobo mothers and the absolute joy and zest for life of their infants can be seen in a YouTube clip at <www.wtmsources.com/107>. The documentary is about a young bonobo called Beny who was sold as a pet after his mother was killed by poachers. Fortunately, he was rescued by the Belgian conservationist Claudine André, who took him to her wonderful bonobo sanctuary, Lola Ya Bonobo in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and later released him back into the Congo forest. While the documentary’s commentary is superficial, the short accompanying film that discusses its production contains two very revealing comments. The first comment was made by Tixier, who said that ‘The choice to do a film about bonobos was because they’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man. They’re the only animals capable of creating the same “gaze” as a human. When you look at a bonobo you’re taken aback because you can see behind the eyes it’s not just curiosity, it’s understanding. We see human beings in the eyes of the bonobo.’ The second was provided by the film’s animal advisor, Patrick Bleuzen, who remarked that ‘Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience.’

This revealing photograph captures the human-like gaze of the bonobo Kanzi