‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 8 The Greatest, Most Heroic Story Ever Told

Chapter 8:9 Early Sobered Adolescentman

The species: the first half of Homo habilis’ reign — 2.4 to 1.4 million years ago

The individual now: 12 and 13 years old

The Early Sobered Adolescent Stage (of Humanity’s Adolescence) signals the end of childhood and represents the time when we fully encounter the sobering imperfections of life under the duress of the human condition.

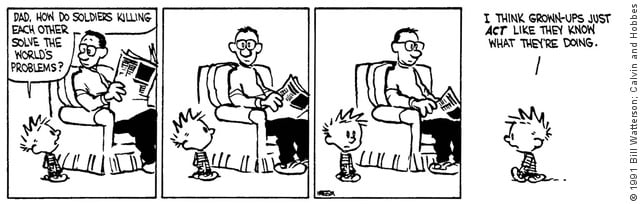

Throughout childhood we saw how the frustration with being criticised for searching for knowledge continued to increase until, in late childhood, the child’s exasperation and resentment caused him to angrily lash out at the ‘injustice of the world’. What happens at the end of childhood is that the child realises that physical retaliation doesn’t make any difference and that the only possible way to solve the frustration is to find the reconciling understanding of why the criticism he is experiencing is not deserved. Of course, as just pointed out in par. 731, the more upset developed in the human race as a whole, the more children also became worried by the upset in the world around them. While resigned adults became accomplished at overlooking the hypocrisy of human life because of its human-condition-confronting implications, children in their naivety could still see it. They asked: ‘Mum, why do you and Dad argue all the time?’ and ‘Why are we always worried about having enough money?’ and ‘Why are we going to a big, expensive party when the family down the road is so poor?’ and ‘Why is everyone so lonely, unhappy and preoccupied?’ and ‘Why are people so fake and artificial?’ and ‘Why is the only thing people talk about when they meet each other is such superficial things as the weather or the football?’ and ‘What is religion?’ and ‘Why do people pray?’ and ‘Who is God?’ and ‘Why do people make awful jokes?’ and ‘Why are there wars?’ (as the following cartoon by Bill Watterson poignantly depicts) and ‘Why are there pictures about sex everywhere?’ and ‘Why did those people fly those planes into those buildings?’ And the truth is, these are the real questions about human life, as this quote by the Nobel Prize-winning biologist George Wald acknowledges: ‘The great questions are those an intelligent child asks and, getting no answers, stops asking’ (Introduction to The Fitness of the Environment, Lawrence J. Henderson, 1958, p.xvii). Children ‘stop[ped] asking’ the real questions—stopped trying to point out the all-important and obvious-if-you-are-still-looking-at-the-world-truthfully, yet almost totally unacknowledged proverbial ‘elephant in the living room’ issue of the human condition—because they eventually realised that adults couldn’t answer their questions; and, more to the point, they were made distinctly uncomfortable by them. The novelist George Eliot (the pen-name of Mary Ann Evans) wrote that ‘Childhood is only the beautiful and happy time in contemplation and retrospect: to the child, it is full of deep sorrows, the meaning of which is unknown’ (1844; George Eliot’s Life, as Related in Her Letters and Journals, 2010, p.126 of 518). The only reason ‘the meaning of’ the ‘deep sorrows’ of children was ‘unknown’ to adults was because adults live in denial of the human condition. A Newsweek article that discussed childhood stress was bordering on this truth when it said, ‘Parents are frequently wrong about the sources of stress in their children’s lives, according to surveys by Georgia Witkin of Mount Sinai Medical School; they think children worry most about friendships and popularity, but they’re actually fretting about the grown-ups [and their world]’ (‘Stress’, Jerry Adler, May 1999; see <www.wtmsources.com/177>). The author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry articulated the child’s point of view beautifully in his celebrated 1945 book The Little Prince, when he had the Little Prince say, ‘grown-ups are certainly very, very odd’ (p.41 of 91). Resigned and unresigned minds have lived in two completely different worlds; they have been like different species, each almost invisible to the other. The renowned writer Robert Louis Stevenson described the situation thus: ‘And so it happens that although the paths of children cross with those of adults in one hundred places every day, they never go in the same direction; nor do they even rest on the same foundations’ (Child’s Play, 1878; as quoted at the beginning of the 1997 film The Colour of the Clouds). So in the final stages of childhood it was not only the issue of the imperfections of their own behaviour that so troubled children, but also the issue of the imperfections of the human-condition-afflicted world around them—a psychological collusion that sees children mature from frustrated, extroverted protestors into sobered, deeply thoughtful, introverted adolescents. It’s a very significant transition in our psychological journey, from the relatively human-condition-free state to the very human-condition-aware state, that is actually recognised by the fact that we separate those stages into childhood and adolescence—a demarcation even our schooling system reflects by having children graduate from what is generally called primary school into secondary school at 12 to 13 years of age. As mentioned earlier, this critical juncture in our species’ development was also recognised by anthropologists when they changed the name of the genus from Australopithecus (meaning ‘southern ape’) to Homo (meaning ‘man’); ‘Childman’, the australopithecines, became ‘Adolescentman’, Homo. And so it was in the lives of the earliest Homo, Homo habilis, that this deeply introspective, thoughtful and sobered state of mind would have existed.