Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The Human Condition Explained

Part 3:11F Hollow Adolescentman

The Hollow Final Adulthood Stage of Adolescent Humanity

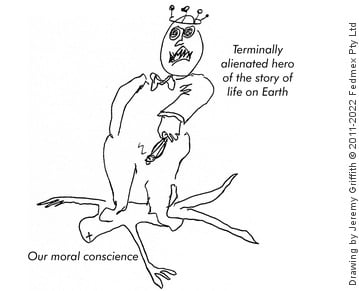

The Hollow Adolescentman stage represents the time when many post-40-year-olds became disillusioned with the treacherous, extremely dishonest and deluded born-again existence and returned to the upsetting battle to champion the ego over the condemning instincts. As a result, however, of this desperate turnaround was that they became even more upset and embattled—in fact, horrifically punch-drunk and soul-destroyed—hollow 50-year-old-plus people.

The species: the Born-again and Hollowman stages are both characteristic of Homo sapiens sapiens’ reign—0.05 million (50,000) years ago to the present day

The individual: 50 plus years old

Having succumbed to the born-again, pseudo idealistic, completely selfish, ‘do good to feel good’ way of coping with the, by now, extremely upset human condition, many in the 50-year-old-plus camp became so disillusioned with the extreme delusion, dishonesty and treachery of that way of coping that they returned to the upsetting battle of championing the ego over our ignorant instincts. But doing so could only mean becoming even more upset—that is, angry, egocentric and alienated—than they were when they were initially driven, through being so extremely upset, to adopt the pseudo idealistic way of living in the first place. In the context of that extraordinarily honest Japanese proverb included earlier, which described the stages of maturation under the duress of the human condition—‘At 10 man is an animal, at 20 a lunatic, at 30 a failure, at 40 a fraud and at 50 a criminal’—this was the 50-year-old ‘criminal’ stage where men in particular had become so angry, so punch-drunk, so bitter and vengeful that they brutally and completely repressed the condemning voice of their ideal-behaviour-demanding, cooperatively orientated soul and were now adrift in an empty, hollow, soul-less wilderness.

This ‘grumpy old man’, vengeful, burnt-out, empty, sad existence that men typically inhabited when they reached 50 and beyond was perfectly described by T.S. Eliot in his 1925 poem The Hollow Men: ‘We are the hollow men / We are the stuffed men / Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw. Alas! / Our dried voices, when / We whisper together / Are quiet and meaningless / As wind in dry grass / Or rats’ feet over broken glass / In our dry cellar // Shape without form, shade without colour / Paralysed force, gesture without motion //…This is the dead land / This is cactus land / Here the stone images / Are raised, here they receive / The supplication of a dead man’s hand / Under the twinkle of a fading star // Is it like this / In death’s other kingdom / Waking alone / At the hour when we are / Trembling with tenderness / Lips that would kiss / Form prayers to broken stone // The eyes are not here / There are no eyes here / In this valley of dying stars / In this hollow valley / This broken jaw of our lost kingdoms // In this last of meeting places / We grope together / And avoid speech / Gathered on this beach of the tumid river //…Between the desire / And the spasm / Between the potency / And the existence / Between the essence / And the descent / Falls the Shadow /…This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper’ (T.S. Eliot Selected Poems, 1954, pp.77-80 of 127).

For women, ageing during humanity’s adolescence was, in its own way, similarly horrific because it meant the loss of the image of innocence that they depended on for reinforcement, the loss of their sex-object ‘attractiveness’, and with it, the loss of their meaning in the world—a source of meaningfulness that all women’s magazines that focus entirely on how to be ‘attractive’ are testament to. When women are young their beauty is generally so empowering it is as if they own the world, but when they become older and their beauty/‘attractiveness’/innocence fades they discover that they have become invisible; when they walk down the street they are no longer noticed. This quote from the French beauty therapist Diane Delaheve describes how devastating it can be for women to lose their sex appeal: ‘Her eyes, the mirror of her soul, speak nothing but despair. Her face may have kept its beauty, but it has become a picture of affliction. For some women, the prospect of age is sheer tragedy, worse than death, which might be seen as an escape’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 4 Sept. 1988). So, while men become ‘hollow’, women become ‘invisible’; when observing older couples walking together in the park you can see how united they are by their comparable afflictions. (Again, the roles of men and women under the duress of the human condition will be fully explained later in Part 7:1.)

An added dimension to the situation faced by older women is that in not being as responsible for the main battle of having to champion the ego over ignorance as men were, women found that their role of living in support of the battle was limited. It has been observed that a woman’s life progressed from ‘bimbo, breeder, babysitter to burden’. Men, on the other hand, were directly participating in the battle of championing the ego and therefore didn’t face the prospect of one day feeling they were a ‘burden’ to the extent that women did. In his 1993 book The Fisher King & The Handless Maiden, the American Jungian analyst Robert A. Johnson relates the myth of the Handless Maiden, which tells of a miller who makes a deal with the devil in order to complete more work with less effort. The devil demands the miller’s daughter as payment: ‘The miller is desolate but unwilling to give up his much expanded mill, so he gives his daughter to the devil. The devil chops off her hands and carries them away’ (p.59 of 103). Waited on by her newly prosperous family, the handless maiden is content for a time, until her growing sense of desperation sends her out to the forest alone. Johnson explains that the cry of women, like that of the handless maiden, is ‘What can I do? I feel so useless or second-rate and inferior in this world that puts its women on the rubbish heap when they are through with courtship and childbearing!’ (p.56).

Later in Part 7:2 the following drawing by British cartoonist and caricaturist Ralph Steadman will be discussed in some detail because it depicts with such incredible honesty the horror of the human condition—indeed, I have used the main dragon in this cartoon as the inspiration for my drawing above of the 50-year-old-plus stage; his eyes show the hollowness that T.S. Eliot spoke of: ‘This is the dead land / This is cactus land.’ The desperately tragic, sickly state of older women is also apparent in this cartoon.