Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The New Biology

Part 8:4 How humans acquired our moral soul and conscience — our original instinctive orientation to behaving unconditionally selflessly

Part 8:4A Introduction

While a description of how we humans acquired our unconditionally selfless moral instinctive self or soul and conscience was very briefly presented in Parts 3:4 and 4:4D, a comprehensive description now needs to be provided.

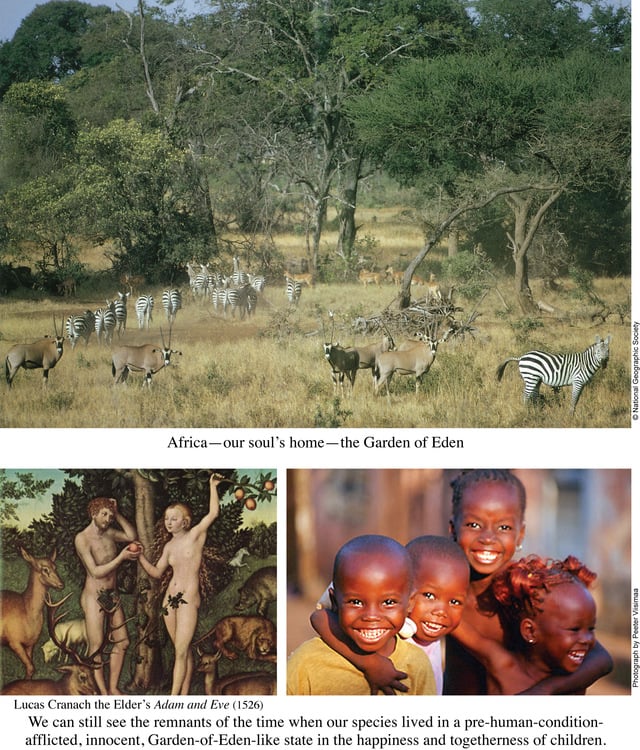

As has previously been described in Parts 4:6 and 5:2, our mythologies and most profound thinkers have recognised that our distant ancestors lived in a pre-conscious, pre-human-condition-afflicted, innocent, unconditionally selfless, genuinely altruistic, fully cooperative, universally loving, peaceful state. As Richard Heinberg’s summary of his research into the subject of our memory of a ‘Garden of Eden’ ‘Golden Age’ in our species’ past states, ‘Every religion begins with the recognition that human consciousness has been separated from the divine Source, that a former sense of oneness…has been lost…everywhere in religion and myth there is an acknowledgment that we have departed from an original…innocence’ (Memories & Visions of Paradise, 1990, pp.81-82 of 282). The eighth century Greek poet Hesiod also referred to this ‘Golden Age’ in our species’ past in his poem Works and Days: ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind / Nor e’er decrepit age misshaped their frame…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…Dying they sank in sleep, nor seemed to die / Theirs was each good; the life-sustaining soil / Yielded its copious fruits, unbribed by toil / They with abundant goods ’midst quiet lands / All willing shared the gathering of their hands.’

Even the meaning and origin of the words associated with our moral nature reveal our awareness of the extraordinarily loving, ideal-behaviour-expecting, ‘good-and-evil’-differentiating, sound nature of our instinctive self or ‘psyche’ or ‘soul’, the ‘voice’ or expression of which is our ‘conscience’. The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines our ‘conscience’ as our ‘moral sense of right and wrong’, and our ‘soul’ as the ‘moral and emotional part of man’, and as the ‘animating or essential part’ of us. And the Penguin Dictionary of Psychology says: ‘psyche: The oldest and most general use of this term is by the early Greeks, who envisioned the psyche as the soul or the very essence of life’ (1985). Indeed, the ‘early Greek’ philosopher Plato said about our born-with, instinctive self or soul’s ideal or ‘Godly’ behaviour-expecting moral nature, that we humans have ‘knowledge, both before and at the moment of birth…of all absolute standards…[of] beauty, goodness, uprightness, holiness…our souls exist before our birth’ (Phaedo, tr. H. Tredennick). He went on to write that ‘the soul is in every possible way more like the invariable’, which he described as ‘the pure and everlasting and immortal and changeless…realm of the absolute…[our] soul resembles the divine’ (ibid).

The philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev also truthfully acknowledged the recognition within us all of a past innocent, uncorrupted instinctive self or soul when he wrote that ‘The memory of a lost paradise, of a Golden Age, is very deep in man’ (The Destiny of Man, 1931, tr. N. Duddington, 1960, p.36 of 310); while the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau also expressed what we all intuitively do know is the truth about our species’ past innocent existence when he wrote that ‘nothing is more gentle than man in his primitive state’ (On The Origin of Inequality, 1755; The Social Contract and Discourses, tr. G.D.H. Cole, 1913, p.198 of 269).

Yes, as philosopher John Fiske wrote about our moral nature: ‘We approve of certain actions and disapprove of certain actions quite instinctively. We shrink from stealing or lying as we shrink from burning our fingers’ (Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy, 1874, Vol. IV, Part II, p.126). And our moral instinctive self or soul is not only concerned with not ill-treating others, it is also deeply concerned with their welfare. When Joe Delaney, a professional footballer, acknowledged that ‘I can’t swim good, but I’ve got to save those kids’, just moments before plunging into a Louisiana pond and drowning in an attempt to rescue three boys (‘Sometimes The Good Die Young’, Sports Illustrated, 7 Nov. 1983), he was considering others above his own welfare. The truth is everywhere we look we see examples of humans behaving unconditionally selflessly, such as those who sacrifice their lives for moral or ethical principles, or show charity to the less fortunate. Indeed, now that we can explain the human condition it becomes clear that since the human condition emerged when we became conscious some two million years ago, every generation of humans has suffered becoming self-corrupted in an unconditionally selfless effort to add to the accumulation of knowledge that might one day liberate humanity from the human condition—to again use the words from The Man of La Mancha, every generation has altruistically ‘march[ed] into hell for a heavenly cause’ (The Impossible Dream, Joe Darion, 1965).

Our species’ unconditionally selfless moral nature is indeed a wonderful phenomenon. The philosopher Immanuel Kant was so impressed with it he had these words inscribed on his tomb: ‘there are two things which fill me with awe: the starry heavens above us, and the moral law within us’ (Critique of Practical Reason, 1788). Charles Darwin was similarly awed by the existence of our moral instincts, writing that ‘the moral sense affords the best and highest distinction between man and the lower animals’ (The Descent of Man, 1871, ch.4).

The poet Alexander Pope, however, was not so impressed by our ‘divine’-like, ‘absolute standards…[of] beauty, goodness, uprightness, holiness’-expecting, ‘animating’, ‘very essence of life’, ‘awe’-inspiring, ‘best and highest distinction’-deserving, ‘moral and emotional’, ‘essential part’ of us, pointing out that ‘our nature [is]…A sharp accuser, but a helpless friend!’ (An Essay on Man, Epistle II, 1733). And he was right in the sense that, as has been made very clear, our conscience has been ‘a sharp accuser, but a helpless friend’; it has criticised us aplenty when what we needed was redeeming understanding of our ‘good-and-evil’-afflicted, corrupted or ‘fallen’ present human condition—which, thank goodness, we now at last have.

Yes, paradoxically we couldn’t afford to face the truth that our ‘awe’-inspiring, ‘best and highest distinction’-deserving, moral soul is our instinctive memory of an unconditionally selfless, all-loving past until we could explain our present ‘sharp accus[ation]’-from-our-conscience-deserving, soul-devastated, innocence-destroyed, angry, egocentric and alienated condition—as the psychologist Ronald Conway noted about our human-condition-avoiding, mechanistic attitude to the subject of our soul: ‘Soul is customarily suspected in empirical psychology and analytical philosophy as a disreputable entity’ (The Australian, 10 May 2000). But now that we have the fully accountable, human psychosis-addressing-and-solving, truthful explanation of the human condition we can acknowledge what our soul is, and, most significantly, heal our species’ psychosis or ‘soul-illness’. Yes, since psyche means ‘soul’ and osis, according to Dictionary.com, means ‘abnormal state or condition’, we can at last ameliorate or heal our species’ psychosis, its alienated, psychologically ‘ill’, ‘abnormal state or condition’.

While we can now heal our species’ psychosis, and while our mythologies, profound thinkers and the meanings behind some of the most used words recognise that we humans did once live in an unconditionally selfless, all-loving, moral instinctive state, a very great mystery remains, which is how could we humans have possibly acquired such a ‘distinct’ from other ‘animals’, ‘awe’-inspiring but ‘sharp accus[ing]’ instinctive orientation?

To look at the biology involved in the question of the origin of our species’ extraordinary moral nature. As was explained in Parts 8:2 and 8:3, while the gene-based system for developing the order of matter on Earth is powerfully effective—it developed the great variety of life we see on Earth—it has one very significant limitation, which arises from the fact that each sexually reproducing individual organism has to struggle and compete selfishly for the available resources of food, shelter, territory and a mate it requires if it is to successfully reproduce its genes. What this means is that integration, and the unconditionally selfless cooperation that it depends upon, cannot normally develop between one sexually reproducing individual and another; which then means that integration beyond the level of the sexually reproducing individual—that is, the coming together or integration of sexually reproducing individuals to form a new larger and more stable whole of sexually reproducing individuals, the Species Individual—can also not normally develop. Thus, it appeared that Negative Entropy’s, or ‘God’s’, development of order of matter on Earth had come to a stop at the level of the sexually reproducing individual. The integration of the members of a species into the larger whole of the Specie Individual could seemingly not be developed.

What all this means is that only a degree of cooperation and thus integration could be developed between the sexually reproducing individual members of a species before the competition between them became so intense that a dominance hierarchy had to be employed to contain the divisive competition; and, in fact, that is where most animal species are stalled in their ability to integrate. They could become to a degree integrated (what has been termed ‘social’), but not completely integrated into one new larger organism or whole. Certainly each sexually reproducing individual could be either temporarily (in the case of large animals like wolves) or permanently (in the case of small animals like ants and bees) ‘elaborated’, made larger, thus allowing greater integration of matter to develop within the sexually reproducing individual, but the sexually reproducing individuals (the wolf packs or the ant/bee colonies) of such species were still engaged in competition with each other. It seemed that the integration of sexually reproducing members of a species and thus the full integration of the members of a species into a Specie Individual could not be achieved; Negative Entropy, or ‘God’, had seemingly developed as much order of matter on Earth as it could.

HOWEVER, the integration of matter hadn’t come to an end because a way was found by Negative Entropy, or ‘God’, to integrate the members of a species into the larger whole of the Specie Individual, AND it was our ape ancestors who achieved this extraordinary step. As it says in Genesis in the Bible, we humans once lived ‘in the image of God’ (1:27), we were once a fully cooperative, unconditionally selflessly behaved, completely integrated species; we did once live in ‘the Garden of Eden’ (3:23) state of original cooperative, loving, innocent togetherness, then we became conscious, took the ‘fruit’ ‘from the tree of…knowledge’ (3:3, 2:17), and, as a result, ‘fell from grace’ (derived from the title of Gen. 3, ‘The Fall of Man’) because we became divisively behaved sufferers of the human condition, supposedly deserving of being ‘banished…from the Garden of Eden’ (3:23) of original innocent togetherness, and left ‘a restless wanderer on the earth’ (4:14); left in our present, immensely upset, psychologically distressed condition, a state we can now at last emerge from because we can finally explain and thus compassionately understand why we had to search for ‘knowledge’ and suffer becoming corrupted. We can explain that we upset humans are not ‘unGodly’ after all; that we had to master our conscious mind in order to be able to securely manage the development of order of matter from our knowing, understanding position.

In his wonderful 1807 poem Intimations of Immortality, William Wordsworth gave this rare honest description of our species’ tragic journey from its original soulful, innocent, instinctive, moral state to its present soul-devastated, often-immoral, apparently—but, as has now been explained, not actually—non-ideal or, to use religious terminology, ‘unGodly’ state: ‘The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star…cometh from afar…trailing clouds of glory do we come / From God, who is our home.’ In the poem Wordsworth described how quickly this ‘life’s Star’ of our ideal, moral, ‘God[ly]’ ‘Soul’ that is ‘with us’ when we are born becomes corrupted as we grow up in the human-condition-afflicted world of today: ‘There was a time when meadow, grove, and streams / The earth, and every common sight / To me did seem / Apparelled in celestial light / The glory and the freshness of a dream / It is not now as it hath been of yore / Turn wheresoe’er I may / By night or day / The things which I have seen I now can see no more… I know, where’er I go / That there hath past away a glory from the earth…Thou Child of Joy / Shout round me, let me hear thy shouts, thou happy Shepherd-boy! // Ye blessed Creatures…Whither is fled the visionary gleam? / Where is it now, the glory and the dream? // Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting… Heaven lies about us in our infancy! / Shades of the prison-house begin to close / Upon the growing Boy…Forget the glories he hath known / And that imperial palace whence he came.’

So THE GREAT QUESTION is, how did Negative Entropy, or ‘God’, achieve the amazing integration of our human forebears into the Specie Individual? How did our human ancestors develop the fully integrated state, the instinctive memory of which is our unconditionally selfless, genuinely altruistic, moral self or ‘soul’, the ‘voice’ or expression of which in us is our conscience? What is the biological origin of our species’ extraordinary moral nature?