Part 5

Our Denials Exposed

Part 5:1 How understanding of the human condition was found

The Adam Stork story reveals that we humans became upset when we became conscious. Our pre-conscious, instinct-controlled ancestors weren’t the ‘savage’, ‘barbaric’, ‘primitive’ (in the sense of being divisively behaved), ‘wild-animal’, ‘beast-like’ ‘brutes’ they have been portrayed as in every documentary and movie about early humans—rather, we immensely upset modern humans are all of those things. But without the explanation of the human condition the upset human race had to defend itself somehow, and so the contrived excuse we came up with was to blame our present-day angry, egocentric and aggressive behaviour on supposed savage competitive and aggressive animal instincts from our pre-conscious past. This contrivance didn’t admit that there is a psychosis involved in our human behaviour, even though so many of the words we use to describe our behaviour acknowledge this underlying influence, such as ‘alienated’, ‘psychotic’, ‘depressed’, ‘deluded’ and ‘artificial’. Nor did this ‘genes are selfish and that is why we are’ defence recognise the obvious influence consciousness—a uniquely human feature—has on our behaviour. It also ignored what all our mythologies recognised—that our ancient ancestors lived in a Garden-of-Eden-like state of gentle and cooperative innocence, the instinctive ‘voice’ of which is our moral conscience. But despite the fact that blaming our upset on our instincts is such a flawed and transparently false excuse, upset humans had to believe in it because it was all that was holding at bay the suicidal depression that thinking about their immensely corrupted state caused. Facing the issue of the human condition has been impossible for the upset human race.

The quote that the pre-eminent philosopher of the twentieth century, Sir Laurens van der Post (1906-1996), most frequently cited in his writing is one I mentioned earlier, by the esteemed English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins: ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed’ (from the sonnet No Worst, There Is None, 1885). As his writings reveal, Sir Laurens’ great interest was the human condition and this passage obviously summarised for him the essence of the problem of the suicidal depression—the ‘cliffs of fall’—that was preventing upset humans from confronting the human condition and thus enabling it to be understood or ‘fathomed’.

Unless you were exceptionally well-nurtured in your infancy and childhood and therefore free of upset, the issue of the human condition was an impossible subject to go near. Having looked into and found the understanding of the human condition, I necessarily had to have been exceptionally well-nurtured. Within the spectrum of upset that has naturally existed across the human race since upset first emerged, with its degrees of denial and alienation, there have always been some denial-free, alienation-free, unresigned, truthful thinkers. While in earlier, pre-scientific times, religions were sometimes formed around the sound, truthful lives and words of these rare unresigned, denial-free thinkers or prophets, in contemporary times they simply represent another variety of thinker. Once mechanistic science found sufficient insights into the mechanisms and workings of our world for the truth about the human condition to finally be able to be assembled, these denial-free thinkers were needed to undertake that task. All that I have done to find the understanding of the human condition is assemble the relevant clues about the mechanisms and workings of our world that mechanistic science found through centuries of painstaking enquiry. It follows that to have done this—and I was assisted in the assemblage of that truth by the work of other denial-free thinkers—I had to be an unevasive, denial-free thinker.

Most importantly, the fundamental truth that emerges from the biological understanding of the human condition is that all humans are equally good, just differently upset from their various encounters with the heroic battle that the human race has been engaged in. In a nutshell, all humans are variously embattled but we are all equally good. We no longer have to rely on a dogmatic assertion that ‘all men are created equal’, purely on the basis that it is a ‘self-evident’ truth, as the United States’ Declaration of Independence proclaims—because we can now explain, understand and know that that is a fundamental truth. Human upset is a result of humans’ unavoidable and necessary heroic struggle against ignorance. Understanding the cause of the upset state of the human condition eliminates the possibility of the prejudicial views of some people being good and therefore superior and others being bad, evil, ungodly and therefore inferior and unworthy. Now that we have understanding of the great and necessary battle that humanity has been waging, the whole concept of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, of superior and inferior, disappears from our conceptualisation of ourselves. So, those who have been lucky enough to not have been caught up in the most intense part of the battle that humanity has been waging, and who are thus relatively free of upset or innocent, are no better or superior or more worthy than anyone else—they simply represent just one of the innumerable, different states of upset that humanity can and had to draw on to complete its heroic journey to find the liberating understanding of the human condition. All humans can now talk freely about all the different states of upset without there being any implication of either superiority or inferiority, worthiness or unworthiness; more to the point, we need to talk about those different states now in order to make sense of the world in which we have all been living. Alienation is the subject that makes sense of human behaviour, so to understand human behaviour, which is what we have to do to understand ourselves, alienation has to be acknowledged. As mentioned earlier, the great Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing acknowledged this when he wrote that ‘Our alienation goes to the roots. The realization of this is the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life.’

The simple truth is that to have been able to look into and explain the human condition I had to have been exceptionally sheltered from all the upset in the world—and I was. I grew up in this historically extremely isolated country of Australia, probably the last place of innocence in the world, and I grew up in the Australian countryside or bush, which is even further removed from all the upset that concentrates in towns and cities. I also benefited very greatly from being born immediately after the Second World War, on 1 December 1945, seven months after Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945 and four months after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 respectively—acts that brought the Second World War to an end. As previously mentioned, after such terrible bloodletting as occurred in the Second World War, which amount to a valving off of upset, there is always a period of enormous relief and freshness, especially among those on the side of victory against such tyranny. In fact, there can’t have been any other period in modern history where there was as much innocent idealism and optimism as the ‘flower power’, ‘Age of Aquarius’ era of the 1960s when the post-war ‘baby boom’ generation was growing up. Science, the organised and systemised pursuit of knowledge, was sufficiently developed for the biological explanation of the human condition to be found, and there also seemed to be—and, as it turned out, was—enough sound innocence in the population for that explanation to be truthfully and thus effectively assembled by someone exceptionally innocent and thus exceptionally free of denial.

I was also fortunate to have attended two of the best schools in the world, both of which were also situated in rural Australia: Tudor House school at Moss Vale in New South Wales for my junior schooling, and Geelong Grammar School (GGS) in Victoria for my senior education. The ethos of GGS, which was established by Australia’s greatest ever educator, Sir James Darling, focused on fostering the souls of students, rather than their intellect (virtually all schools focus on academic achievement and egocentric competition in sport). For example, as part of GGS’ curriculum students spend a year in the Victorian mountains at a campus called ‘Timbertop’, where everyone goes bushwalking every weekend. I absolutely thrived at Timbertop, winning the Natural History Prize and being judged runner-up for Best Boy of The Year even though I performed very poorly in my academic studies. I had all kinds of collections, even of all the different animal droppings. I will talk more about Sir James Darling and GGS shortly. Of course, the most important factor by far in my ability to confront the issue of the human condition was the nurturing I received from my mother. As I will describe shortly, it was her soul strength that cultivated and strengthened my soul sufficiently to be able to defy the false world of denial.

I might include this comment about the significance of being conceived towards the very end of the Second World War. I have been involved with a number of adults undergoing primal therapy who, bit by bit, are helped by supportive, encouraging and delving questioning to go back into their memories to therapeutically relive their childhood traumas and to hear the extreme anguish that many of them express from their time in the womb there can be no denying how acutely aware the foetus is of its environment. Unlike most denial-complying mechanistic scientists, practitioners of primal therapy, such as the American Arthur Janov (1924-) (see his many books), know all too well the sensitivity of the foetus to the human-condition-afflicted state of mothers today. An article in TIME magazine (4 Oct. 2010) titled ‘How the first nine months shape the rest of your life: The new science of fetal origins’ recorded this evidence of the sensitivity of the foetus: ‘a study of the health records of more than 88,000 people born in Jerusalem between 1964 and 1976 found that the offspring of women who were in their second month of pregnancy in June 1967—the time of the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War—were significantly more likely to develop schizophrenia as young adults.’ With the upset state of the human condition now explained/understood/defended we can at last safely admit that our ape ancestors lived in an utterly cooperative, harmonious, loving state, and that as a result of that heritage human infants still expect to encounter such an ideal state. In light of this expectation, we can admit therefore how utterly devastating it must be for the foetus to encounter the extreme opposite of that happy, secure, nurturing, loving state—as it was for those developing in the womb of mothers traumatised by the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War. Conversely, it follows that if someone is conceived and raised at a time when there is extraordinary relief and happiness in their society, as I was at the conclusion of the Second World War, that their instinctive self or soul will be exceptionally content, secure and well-adjusted. As I say, the whole post-war 1960s generation was relatively extraordinarily secure and happy and, as a result, idealistic and sound in its thinking and thus visionary—anticipating, as the 1967 ‘Summer of Love’ song Aquarius described, a time of ‘Harmony and understanding, sympathy and trust abounding. No more falsehoods or derisions, golden living dreams of visions…And the mind’s true liberation …We dance unto the dawn of day’ (from the rock musical Hair that premiered in 1967, lyrics by James Rado & Gerome Ragni).

I had an idyllic upbringing that enabled me to look at this subject of the human condition when no one else would. My great fascination and interest is with wildlife, what all the birds and the other animals are doing. As Tim Macartney-Snape mentioned in his Introduction, prior to and after finishing university I spent six years looking for the Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, in the wilds of Tasmania—you can read more about my search at <www.humancondition.com/tasmanian-tiger-search>. I never wanted to be a biologist who sat writing at a desk all day; actually, I don’t at all enjoy writing all day, but I kept finding I could make sense of biological questions. The problem, however, was that the issues that seemed so obvious and important to me—in particular, that there is something extremely wrong with the way humans behave—didn’t seem to bother anyone else. In fact, everyone was carrying on as if the way humans behaved was the way they have always behaved and should behave. As I now understand, adults have lived in a resigned state of denial of the truth of the extreme imperfection of human behaviour today.

Throughout not only my adolescent years but my entire life, I have been consumed with all the issues that denial-free, pre-resigned adolescents struggled with about the apparent wrongness of human behaviour. As I described in Part 3:8, when adolescents started thinking about the issue of the human condition, which is the imperfection of human behaviour today, they almost invariably found they had to resign themselves to living in denial of the subject because their thinking about it eventually brought them into contact with the issue of their own imperfections that arose from their encounters with the upset world during their own infancy and childhood. In my case, while I was consumed with the issue of the human condition like all pre-resigned adolescents have been, unlike other adolescents I didn’t encounter the depressing issue of the human condition within myself and so never had to resign to a life of living in denial of it. Unlike virtually everyone else, I have confronted the issue of the human condition and sought to understand it all my life—the result being the explanation of it that I have presented.

Not having resigned to living in denial of the issue of the human condition, the thoughts that have consumed my mind throughout my life have been vastly different to those of resigned humans who have been practicing all manner of denial, to which they never admit. I was continually running into views that seemed totally wrong to me, and yet everyone except me was upholding those views as true and right. As I have mentioned before, for all those living in denial it is self-evident why denial is such a universal practice but for the relatively innocent who are not yet resigned it is a total mystery—an extremely bewildering situation that, in my case, was only relieved when in my late teenage years my mother gave me a copy of a book by the exceptionally innocent and sound, denial-free thinker, Sir Laurens van der Post (I think it was his 1952 book Venture to the Interior). It was this book, and then Sir Laurens’ two main books about the relatively innocent Bushmen, The Lost World of the Kalahari (1958) and Heart of the Hunter (1961), which I sought out soon after reading the first book, that saved my life—well, saved my soul’s life. These books saved my soul’s life because through Sir Laurens’ depiction of the relatively innocent Bushmen they told me the truth that humans were once, before the emergence of the human condition, totally innocent and free of upset and that the way humans behave now is extremely distorted or corrupted. Sir Laurens’ writings gave me the confirmation I needed to know that my very different unresigned, denial-free way of thinking wasn’t some form of madness. He gave my unresigned, denial-free, innocent instinctive self or soul the strength to carry on and defy the world of denial. When your soul is full of enthusiasm for another true world—a number of my report cards from Tudor House school, which I still have, said I was ‘filled with a great zest for life’—you don’t need a lot of help in life but at some stage you do need someone to reassure you that your view of the world isn’t wrong.

As Tim described in his Introduction, my idealistic, quixotic (labels I was often given as a young man), truthful view of the world first expressed itself in my desire to save the Tasmanian Tiger from extinction. I then switched my focus from the effects of humans’ mad behaviour, such as our destruction of the natural world, to the issue of human behaviour itself. I thought that what was needed was to create a world for humans that was free of extravagant artificiality, so I went off into the bush and built a massive pole-framed workshop and then designed and built a range of furniture that was devoid of that artificiality and ornamentation. In time, however, I realised that there was a deeper issue behind humans’ extravagant way of living and that was the issue of the human condition. Thus in 1975 I began to think and write about that issue, a practice I have carried out every day since then. Typically I write in the early hours of the morning when everyone else is asleep and the air is free of angst and my soul can run free and tell me all the truths and give me all the guidance I need to plumb the depths of the human condition. From the beginning I have trusted my soul and not the world around me; it is the only thing that has never disappointed me.

Hopkins wrote, ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer.’ We can now understand exactly what he meant—if you try to plumb the depths of the human condition you are going to face suicidal depression, unless you go in a state of innocence. Sir Laurens emphasised this fact that only those free of upset can safely investigate the human condition when he wrote that ‘He who tries to go down into the labyrinthine pit of himself, to travel the swirling, misty netherlands below sea-level through which the harsh road to heaven and wholeness runs, is doomed to fail and never see the light where night joins day unless he goes out of love in search of love’ (The Face Beside the Fire, 1953, p.290 of 311). The need to live in denial of truth obviously stops access to truth, that being its purpose—as this amazingly honest posting on a Christian website that was included in Part 4:12J recognised: ‘if there really is hope beyond the human condition, then the Truth that leads to it has to have been established by someone beyond the human condition. Us [denial-complying] humans are way too good at rationalizing truth into any shape that pleases us’ (Jonathan Wise, The Emerging Church, 29 Mar. 2009, accessed 4 Jul. 2009 at: <https://www.jonandnic.com/2009/03/29/the-emerging-church/>). You can’t look into the human condition if you suffer from the human condition.

As described in Section 4:1 of Freedom Expanded: Book 2, Australia’s most celebrated poem is Banjo Paterson’s 1895 The Man From Snowy River. While Australia has an ancient mythology that is grounded in the Dreamtime stories of the Aborigines, it also has a powerful contemporary mythology and The Man From Snowy River is at the centre of them. In fact, Australia’s $10 note (see following image) features Paterson’s image and, in microprint, all the words to The Man From Snowy River.

Mythologies only develop and endure if they contain a resonating deep truth and The Man From Snowy River certainly does. Ostensibly the poem is about a great and potentially dangerous ride undertaken by mountain horsemen to recapture an escaped thoroughbred that joined the brumbies (wild horses) in the mountain ranges, but what the poem is really recognising is that Australia is where the answers about the human condition would finally be found. In the poem the character Clancy of the Overflow persuades the station owner Harrison to let a ‘stripling’ ‘lad’—a boy—on his hardy mountain pony join their expedition to retrieve the escaped thoroughbred; he argues, ‘I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end.’ A boy is the embodiment of the innocence that is needed by mechanistic science ‘at the end’ of its search for understanding of the mechanisms and workings of our world to assemble, from those hard-won but evasively presented insights, the liberating explanation of the human condition. So in the poem that ‘stripling’ ‘lad’ goes beyond where the rest of the horsemen (the alienated adults) dare to go, following the brumbies down the ‘terrible descent’ of a steep mountainside (note the same imagery as Hopkins’ ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer’), where (if you weren’t sufficiently innocent and thus sound enough) ‘any slip was death’ (to confront the unconfrontable issue of the human condition), to recapture the thoroughbred from the impenetrable mountain ranges (retrieves the all-precious escaped truth from the depths of denial/alienation). The poem describes how the boy ‘ran [the brumbies]…till their sides were white with foam / He followed like a bloodhound on their track / Till they halted, cowed and beaten—then he turned their heads for home’ and ‘brought them back’ (he fought all the denial and its alienation that has been enslaving the world to a standstill until it finally gave up the truth).

Whilst innocence was unbearably confronting during the search for understanding and was therefore often persecuted, it was needed ‘at the end’ to synthesise the denial-free explanation of the human condition from mechanistic science’s hard-won but evasively presented insights.

The Biblical story of David and Goliath contains the same recognition of innocence eventually slaying the giant, which is our species’ alienated state of denial.

In the great European legend of King Arthur, the wounded (alienated) Fisher King whose realm was devastated (humans unavoidably made their world an expression of their own madnesses) could only have his wound healed, and his realm restored, by the arrival in his kingdom of a simple, naive boy. The boy’s name is Parsifal, which, according to the legend, means ‘guileless fool’. To the alienated only a naive, ‘guileless fool’ would dare approach and grapple with the confronting truths about our divisive condition. The American Jungian analyst Robert A. Johnson gave an interpretation of this legend in his 1974 book He, Understanding Masculine Psychology. Johnson said firstly that ‘Alienation is the current term for it [the state of humans today]. We are an alienated people, an existentially lonely people; we have the Fisher King wound’ (p.12 of 97). He then described how ‘The court fool had prophesied that the Fisher King would be healed when a wholly innocent fool arrives in the court. In an isolated country a boy lives with his widowed mother [as I will explain later it is the male ego that can be especially oppressive of the souls of children—fortunately my father was saint-like in the degree to which he avoided imposing his ego on others]…His mother had taken him to this faraway country and raised him in primitive [innocent] circumstances. He wears homespun clothes, has no schooling, asks no questions. He is a simple, naive youth’ (p.90). Johnson went on to recount that in the myth it is this boy, Parsifal, who, when he becomes an adult, is able to heal the Fisher King’s wound of alienation, so that ‘the land and all its people can live in peace and joy’ (p.94).

The Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen’s 1837 fable The Emperor’s New Clothes contains the same resonating truth that it would take a small boy to break the spell of the denial that has enslaved the human race.

While these and other mythologies have recognised the truth about innocence leading humanity home from its lost state of alienation, they were not the central mythology of their civilisations that The Man From Snowy River has been for Australia. I think that deep in their bones all humans know that Australia is the last place in the world where there is sufficient innocence to explain the human condition, and, not only that, I think they know that this great breakthrough would occur here. As I mention in Section 1:14 of Freedom Expanded: Book 2, in an interview with the Australian television presenter Andrew Denton, Bono, the prophetic lead singer of the rock band U2, said, ‘You do get the feeling in Australia that there’s…something going on down here, a new society being dreamt up…[that in Australia there is] the opportunity to lead the world…to actually just take some moral high ground’, to which Denton joked, ‘You say this to every country you visit.’ Bono responded, ‘The only other country I think has the chance in leadership in terms of creating a new model as Australia would be Canada’ (Enough Rope, ABC-TV, episode 97, 13 Mar. 2006).

Another relevant factor has to be my ancestry. As will be explained in Part 7:4, just as innocence is eroded in individuals through exposure to the upset state of the human condition, so races of humans have had their innocence eroded through exposure to the upset state of the human condition. This means that those races that have been most isolated from all the upset in the world will be the most innocent. Thus the Celts who have lived on the fringes of Europe in Ireland, Scotland, Scandinavia and England (where the Angles and Saxons from Denmark in southern Scandinavia, and the Normans originally from Norway, settled) have to be amongst the most innocent of European races. It makes sense, therefore, that the fact that my father’s great, great, great grandfather was a protestant from County Cavan in Ireland, and presumably his ancestors originally came from Wales where Griffith was originally called Gruffydd, while my mother’s ancestors came from England and Scotland, must have played a part in my ability to look into the human condition. (You can read more about the Celts in my 2003 book A Species In Denial in the section titled ‘The denial-free history of the human race’, which you can go directly to at <www.humancondition.com/asid-the-denial-free-history-of-the-human-race>.)

In truth, you could sit down and work out exactly where these understandings of the human condition were going to come from—you would ask ‘What is a relatively innocent race, what is the most innocent country now, what is the most innocent region of that country, what was the most fortunate period in that country’s recent history, what are the most innocence-cultivating-and-preserving schools in that country?’, and you would come up with the answer. (A Species In Denial contains a section titled ‘Australia’s role in the world’ that talks about this awareness, which you can go directly to at <www.humancondition.com/asid-australias-role>.)

Sir Laurens van der Post, whose deeply influential work I refer to throughout this presentation, grew up in Africa before the human situation there descended into such turmoil—when it was still a place where innocence could survive. Not only that, since Africa was our species’ instinctive self or soul’s original home, it was a place that was exceptionally nourishing of our soul. Interestingly, Sir Laurens was struck by the physical similarity between Africa and the Australian outback or bush, where I grew up, observing: ‘When I first went to Australia…my senses told me at once that here, beyond rational explanation, was a land physically akin to Africa’ (The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955, p.35 of 159). Australia is physically similar to Africa, but without its teeming megafauna. Sir Laurens came out of the innocent realm of natural Africa and that is partly why his soul was still alive and he could write with so much honesty about the human condition.

In his books about the relatively innocent Bushmen race, Sir Laurens acknowledged that we humans do have an innocent, loving soul within us and that we weren’t once brutal savages. I have mentioned how valuable Sir Laurens’ honest writing about the innocence of original humans has been for me—as some indication of just how precious his writing has been to me, my original copies of The Lost World of the Kalahari and Heart of the Hunter are now so tattered from use they are held together by lots of tape and some string.

As I mentioned earlier, Geelong Grammar School was another soul-fostering influence in my life. GGS played down competition in all activities and especially so in sport. It encouraged any talent or interest a boy might have and kept students close to nature by sending them to its wilderness campus, Timbertop, for a whole year of their education, where everyone, including the masters, went on long bushwalks every weekend. Basically GGS was like a supportive, loving, functional parent rather than an indifferent, stand-offish, brutal, tough dysfunctional one. Astonishing as it may sound, Sir James Darling (1899-1995), whose vision made GGS into such a special school, came out to Australia from England at the age of 30 specifically to foster the soundness needed to solve the human condition. Part 10:5, titled ‘Sir James Darling’s Vision of Fostering the Ability to Undertake the ‘Paramount’ Task of Solving the Human Condition in Order to ‘Save the World’, documents in some detail Sir James’ absolutely extraordinary vision, and there is also a longer essay about Darling’s vision available at <www.humancondition.com/darling-longer-essay>. The longer essay describes how Sir James was influenced by the attitude of Kurt Hahn who created Gordonstoun school in Scotland. Kurt Hahn, in turn, was influenced by Plato who, in his great work The Republic, said that the object of education should be to cultivate ‘philosopher guardians’ or ‘philosopher rulers’, who he described as ‘the true philosophers, those whose passion is to see the truth’ (Plato The Republic, tr. H.D.P. Lee, 1955, p.238 of 405). Plato explained: ‘But suppose…that such natures were cut loose, when they were still children, from the dead weight of worldliness, fastened on them by sensual indulgences like gluttony, which distorts their minds’ vision to lower things, and suppose that when so freed [during their upbringing] they were turned towards the truth [during their education], then the same faculty in them would have as keen a vision of truth as it has of the objects on which it is at present turned’ (p.284). He argued, ‘isn’t it obvious whether it’s better for a blind man [an alienated person] or a clear-sighted one [a relatively innocent, ego-unembattled, denial-free person] to keep an eye on anything’ (p.244), adding that ‘If you get, in public affairs, men who are so morally impoverished that they have nothing they can contribute themselves, but who hope to snatch some compensation for their own inadequacy from a political career, there can never be good government. They start fighting for power…[whereas those who pursue a life] of true philosophy which looks down on political power…[should be] the only men to get power…men who do not love it [who are well-nurtured with unconditional love in their upbringing and encouraged during their education to be enterprising and who are thus not insecure and egocentric, excessively in need of reinforcement]…rulers [who] come to their duties with least enthusiasm’ (p.286). It was this Platonic attitude of preserving and fostering the sound, loving, cooperatively orientated, original instinctive self or soul in students that Sir James followed at GGS.

I have been told that the despair Sir James felt after losing so many gifted contemporaries in the First World War, in which he served as an artillery officer, led him to decide that the only way that he could live with the fact that he survived while they did not was to try to live the life of 10 men. So he came here at the age of 30, knowing that Australia was a last refuge for innocence, to take up the headmastership of this small school that drew most of its boys from the rich farming countryside of Victoria and over 30 years he built it up to be one of the most esteemed schools in the world—HRH The Prince of Wales was sent there from the other side of the world for part of his education, which, incidentally, also included Hahn’s Gordonstoun.

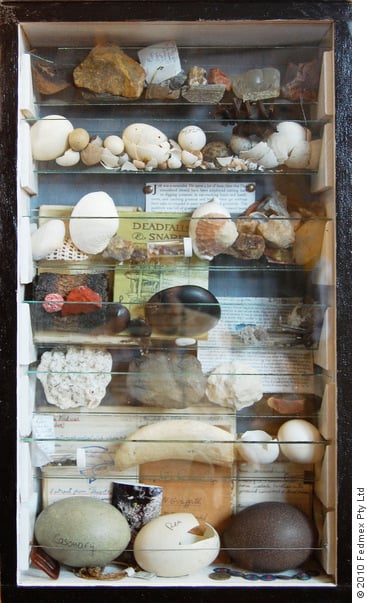

I mentioned how I thrived at Timbertop where I kept all kinds of collections. On the wall of this theatre we have put up an old glass case of mine that holds, amongst other personal treasures, what is left of my egg collection from when I was a boy. These mementos help preserve my soul that still has to fight against a world that is so habituated to living in denial that it is afraid of the truth when it arrives and determinedly resists it.

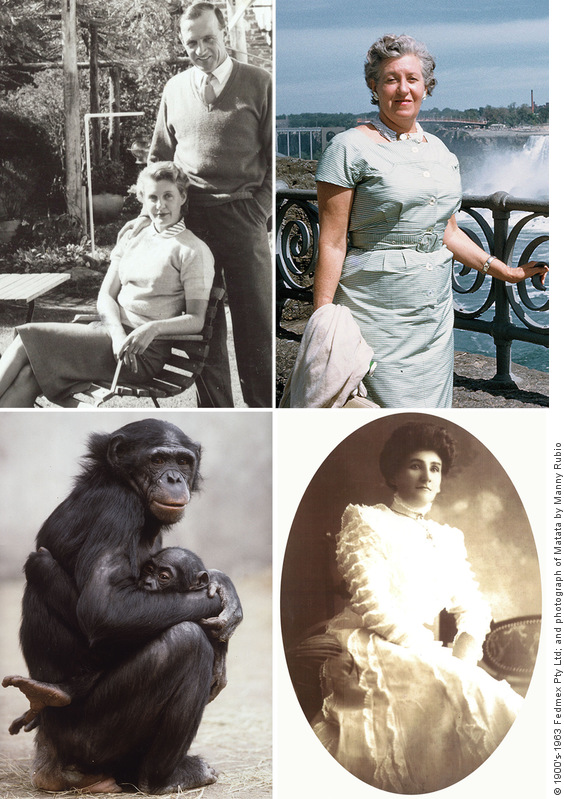

As emphasised, above all else it was my mother’s strength of character and nurturing that made these understandings of the human condition possible, which is why her photograph and that of her mother and grandmother hang on our theatre wall. My mother’s family tree comprises a line of extraordinarily strong women and the following photographs pay tribute to their strength. In the WTM we call such remarkable strength ‘Matata strength’ (after an exceptionally secure, centred and brilliant-at-nurturing-infants female bonobo named Matata, who I will introduce in a moment and whose photo appears alongside the three matriarchs) because, as will be explained in Part 8:4, it dates from when humanity’s female ape ancestors had to have sufficient force of character to bring male aggression from competing for mating opportunities under control.

Clockwise from top left – Norman and Jill Griffith in 1959;

Enid Rush in 1963; Mackie McPherson in the early 1900s; and Matata and Kanzi

The top left photograph is of my mother and father, Jill and Norman Griffith. The photo was taken in 1959 at our sheep station, ‘Totnes’, near the town of Mumbil in the Central West of New South Wales. I would have been 14 years old when this photo was taken. The top right photograph is of my maternal grandmother, Enid Pountney (later Rush), and on the bottom right is my maternal great grandmother, Emily ‘Mackie’ McPherson. You can see in their bearing an indication of their strength of character. As I have said before, the only reason I am able to think about this issue of the human condition is because of my mother’s strength of character. She was so defiant and dismissive of the corrupt ways of our human-condition-afflicted world that she taught me not to believe in it either and instead to believe in another true world, the world of our soul. People would come to our house when I was a boy and my mother was so centred and secure and believing in another true world that they could sense that their alienated state was being dismissed as inconsequential, even irrelevant, even though my mother was never ever rude in her treatment of people. She simply had no time for the frailties of the alienated world. She lived in another true world in which the alienated world had no relevance; it had no meaning for her, as it hasn’t had for me, except for the mystery of it. As I said, you can see in the photographs of my mother and her mother and grandmother the same core strength, the same uprightness, the same defiance and dismissal of all the falseness of this upset, alienated, human-condition-afflicted world. Tim Macartney-Snape’s mother had the same core strength.

The bottom left photograph is of the bonobo Matata with her adopted infant Kanzi. The importance of nurturing and of strong-willed matriarchs in developing a cooperative, integrative society will be explained in Part 8:4, however, to touch upon it briefly now, in matriarchal bonobo society we have living evidence of how important secure and centred females have been in the nurturing of offspring and how strong-willed females have brought the male’s aggressive competition for mating opportunities under control. In common chimpanzee societies there is not the same focus on nurturing, males still dominate and their societies are patriarchal. Matata’s picture is included here in recognition of this strength in women that can be traced right back to our ape ancestors and which Matata, who is an exceptionally centred and secure individual, exemplifies. Those who have studied primates will typically tell you of an extraordinarily secure and strong-willed female in their study group. All primates are trying to develop the nurturing of integrativeness but it is only our ancestors and the bonobos who had the right conditions to achieve it.

The American primatologist Dian Fossey studied gorillas in the mountain forests of Rwanda in Africa for some 18 years. In her 1983 book Gorillas in the Mist, Fossey wrote about a remarkable female gorilla named ‘Old Goat’ who was such ‘an exemplary parent’ (p.174 of 282) that her son ‘Tiger’ ‘was a contented and well-adjusted individual whose zest for living was almost contagious’ (p.186). Fossey is eulogised as a gorilla conservationist but that label presents completely the wrong emphasis. People can’t deal with the true significance of her work, which was that she recognised how social and cooperative gorillas are. Fossey is buried in a grave alongside Digit, a male gorilla who gave his life defending his group against poachers.

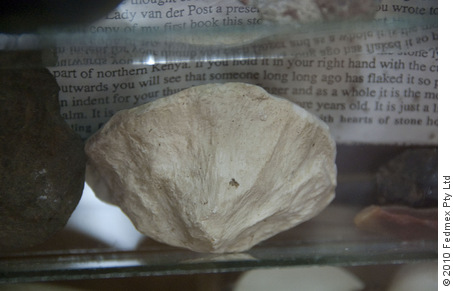

In 1992 my partner Annie Williams and I went to Africa and while there the primatologist Dr Shirley Strum invited us to visit the Pumphouse Gang, a group of baboons she was studying in northern Kenya and about which National Geographic magazine had been writing regular features. (Incidentally, in my egg box on the theatre wall there is a plaster cast of a stone axe, the original of which I found when I was walking across the savannah with the Pumphouse Gang to their night time roost on a huge boulder. As an actual item from the lives of our African ancestors, the original axe head was my most treasured possession and, as such, I sent it to Sir Laurens van der Post as a gift in recognition of how important his life’s work had been to me—he later thanked me, mentioning that he had put it amongst his collection of hundreds of stone axes from Africa!) During our visit I noticed that Strum had on her desk the skull of a baboon named Peggy. Keeping a skull is a bit macabre but she did so in memory of Peggy because she was such an extraordinarily self-assured, strong-willed, authoritative, charismatic individual who led the Pumphouse Gang successfully for many years. In Strum’s words: ‘She [Peggy] was the highest-ranking female in the troop, and her presence often turned the tide in favor of the animal she sponsored. While every adult male outranked her by sheer size and physical strength, she exerted considerable social pressure on each member of the troop. Her family also outranked all the others…another reason for the contentment in this particular family was Peggy’s personality. She was a strong, calm, social animal, self-assured yet not pushy, forceful yet not tyrannical’ (Almost Human: a journey into the world of baboons, Shirley C. Strum, 1987, pp.38-39 of 294). As will be explained in Part 7:1, this ancient strength that was developed in females has sadly had to be oppressed by men for two million years because of its ignorant defiance of men’s corrupt state, and, as a result, is rare amongst women today—but the fact that it is still present in some is a measure of just how strong it must have originally been to have survived this long. It is this exceptional strength in some women, which is so defiant of the upset, false, alienated world, that they can encourage a male child to so believe in another true world that when that boy grows up he is so imbued with awareness of how the world should and could be that he can defy the false world of upset humans. As I say, the importance of my mother’s strength of character and sound, loving, nurturing influence in my life has been so great that this breakthrough understanding of the human condition that I have found has to be almost entirely attributed to her.

In summary, I owe my ability to look into, find and assemble the explanation of the human condition to the relative innocence of my Celtic ancestors and relative innocence of Australia, together with the relative innocence of the 1960s for the presence of a strong soul in the first place; to my mother for nurturing that soul; to Sir James Darling for fostering it; and finally to Sir Laurens van der Post for giving it the confirmation it needed to take on and finally overthrow the alienated world of denial and bring out the truth about the human condition.