Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The Human Condition Explained

Part 3:11 Stages of humanity’s journey to enlightenment

Before beginning this description of the stages that humanity has journeyed through to reach enlightenment, I should mention that while these stages are very briefly discussed towards the end of the 2009 Introductory Video, I have chosen to include that description here, which is relatively early in the transcript of that 2009 Introductory Video. The reason for this re-positioning is that in this written presentation I have now been able to introduce all the concepts necessary to explain the stages, and since the stages are so significant in terms of helping us to better understand ourselves they should be included as soon as possible.

Thus, in having explained the origins of our upset human condition (in Part 3:2), how nurturing led to the development of an unconditionally selfless, altruistic, cooperative, loving existence and moral instinctive self or soul in our ape ancestors (in Part 3:4), what the stages of Infancy, Childhood, Adolescence and Adulthood truly mean (in Part 3:8), and how ending the insecure, human-condition-afflicted Adolescent stage enables the human race to mature to secure, human-condition-free, TRANSFORMED Adulthood, we are now in a position to summarise the whole of our species’ conscious journey from innocent ignorance to enlightenment of our true worth and meaning. We can now explain the psychological journey that the human race has been involved in, and since the psychological journey is the real journey we fully conscious, human-condition-afflicted humans have been involved in, and since it has never before been able to be explained, the following pictures and text provide the first ever true summary of our species’ origins and development. While there have been mountains of books written about human origins, this is the first denial-free, truthful description of our species’ emergence from our ape ancestors. What follows then is the most amazing and epic journey of any species to have existed on Earth—and it’s our own story, the story of the human race.

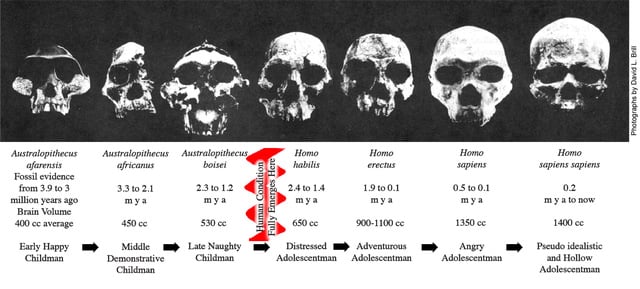

The above sequence of fossil hominid skulls, which date back to our ape ancestors, appeared in the November 1985 edition of National Geographic magazine. While anthropologists have since discovered more varieties of Australopithecus and Homo than those depicted here, these remain representative of the main varieties.

In examining this sequence we can see that a sudden increase in the size of the brain case, and by inference the brain’s volume, occurred around two million years ago. A larger brain case was needed to house a larger ‘association cortex’. As explained in Part 3:3, the ability to ‘associate’ information is what made it possible to reason how experiences are related, learn to understand and become conscious of, or aware of, or intelligent about, the relationship between events that occur through time. It follows that the development of a larger association cortex meant that a greatly increased need for understanding had emerged, which, as will be explained shortly, was a result of the emergence of the dilemma of the human condition. The inference we can take from this evidence then is that the human condition became a full blown problem some two million years ago.

To explain the descriptions of the psychological stages that appear under each of the fossil skulls I need to briefly describe the evolutionary journey we humans have been on since the time of our ape ancestors.

Our early pre-Australopithecine and pre-Homo ape ancestors lived in male-dominated, patriarchal societies in which males aggressively competed for mating opportunities. Then, as outlined in Part 3:4 and as will be fully explained in Part 8:4, through the females’ nurturing of their infants our ape ancestors were able to grow up trained to behave in an unconditionally selfless way, curtailing aggressive male behaviour and producing female-dominated, matriarchal, fully cooperative societies—a process the bonobos are presently in the final stages of developing.

I mentioned in Part 3:4 that this development of unconditionally selfless behaviour had the accidental side effect of liberating consciousness, but at that point in the presentation I wasn’t able to go beyond that to even briefly explain how this occurred, because I hadn’t yet explained Integrative Meaning or the process of Resignation—both of which were necessary to understand how the development of selflessness liberated consciousness. But having now provided those prerequisite explanations, I now can.

Towards the end of Part 3:4, I described how the meaning of existence is to develop the order of matter, and that the ‘glue’ that holds integrated wholes together is selflessness—and that selflessness is cooperative and integrative, while selfishness is divisive and disintegrative. Selflessness is the very theme of existence, so if you can’t acknowledge that central truth you are not in a position to think truthfully and therefore effectively. As was pointed out when Resignation was explained in Part 3:8, having to live in denial of both Integrative Meaning and the all-important theme of integrative behaviour of selflessness, as resigned adults have had to do, meant adopting a dishonest and thus ineffective way of thinking. You can’t build the truth from lies. As Arthur Schopenhauer said, ‘The discovery of truth is prevented most effectively…by prejudice, which…stands in the path of truth and is then like a contrary wind driving a ship away from land.’ Similarly, in her aforementioned Resignation poem Fiona Miller wrote that ‘you [will] spend the rest of life trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze.’ The alienated state that adolescents adopted when they resigned came at the loss of the ability to think truthfully and thus effectively. But how, you may be asking, does Resignation and the loss of our ability to think effectively relate to our ape ancestors who had become orientated to living selflessly? As was also explained in Part 3:4, the limitation of genetics is that it can’t normally develop unconditional selflessness, because such traits tend to self-eliminate. This means that if a species did begin to think truthfully and recognise that selflessness is meaningful and, as a result of this realisation, did begin to behave selflessly, the gene based learning system of natural selection would actively resist such selfless behaviour—it would not allow it to develop, essentially blocking the emergence of truthful, effective thinking and thus consciousness. However, once our ape ancestors were able to develop selflessness through nurturing this impasse was suddenly breached and truthful, selflessness-acknowledging, effective thinking and thus consciousness began to emerge—and sure enough bonobos, which are well on their way to developing the selflessness-dependent, fully integrated state, are fast developing consciousness; they are the most intelligent of all non-human primates. So it can be said that our human brain has been alienated from truthful, effective thinking twice in its history: once when we were like other animals living a competitive, aggressive and selfish existence, and more recently when we lived in fear and thus denial of Integrative Meaning and of the real importance of love and selflessness. (As was pointed out when describing the horrific alienating consequences of Resignation in Part 3:8, resigning to a life of denial of any truths that brought the issue of the human condition into focus meant that we died in soul and in mind: we killed off our instinctive self or soul and we stopped using our conscious mind to think truthfully and thus effectively.) This is an extremely abbreviated account of how we humans became conscious—a longer summary will be given in Part 8:4C, while the complete description will be provided in Part 8:7B.

The descriptions given below the picture of the various fossil hominid skulls document the stages humanity progressed through as this liberated consciousness developed. The names I’ve ascribed to each stage indicate parallels with our own human life-stages. This parallel occurs because the stages that we, as conscious individuals, progress through are the same stages our human ancestors progressed through—‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’: our individual consciousness necessarily charts the same course that our species’ consciousness has taken as a whole. Eugene Marais recognised this when he wrote that ‘The phyletic history of the primate soul can clearly be traced in the mental evolution of the human child’ (The Soul of the Ape, written between 1916-1936 and published posthumously in 1969, p.78 of 170). Wherever consciousness emerges it will first become self-aware, then it will start to experiment with its power to effectively understand and thus manage change, then it will seek to understand the meaning behind all change, and from there it will obviously try to comply with that meaning. In the case of consciousness developing in us individually and in our ancestors, that journey was disrupted by our necessary search for the understanding of why we did not comply with the integrative, cooperative meaning of existence. As described at the beginning of Part 3:8, adolescence is the stage in the development of consciousness where the search for identity takes place, where the search for understanding of the meaning behind change, and the conscious organism’s relationship to that meaning, occurs. In the case of our lives individually, and that of our species, the identity we needed to find understanding of was why we were behaving divisively when the meaning of existence was to behave cooperatively and lovingly. Until we could answer that question we, individually and collectively, were stuck in adolescence—we were stalled searching for our identity, for understanding of ourselves. Our individual and species’ development has been waylaid, or, as psychologists say, ‘arrested’ in adolescence by our inability to understand why we had become divisively behaved. Only with understanding of why we were less-than-ideally behaved could we individually and collectively mature from insecure adolescence to secure adulthood.

To go over this important point again (it was initially raised at the beginning of Part 3:8), since the human race as a whole has not—until now—been able to understand the dilemma of the human condition, humans haven’t been able to properly enter adulthood. When stages of maturation aren’t properly completed it doesn’t mean subsequent growth stages don’t take place, they do, but if a previous stage isn’t properly fulfilled those subsequent stages are greatly compromised by the incomplete preceding stages. People do grow up, but in a state of arrested development. Without the explanation of the human condition humans have been insecure, not properly developed—in fact, preoccupied with still trying to validate themselves, prove that they are good and not bad, find some relief from the insecurity of the human condition. It is only now with understanding of the human condition found that humans will be able to complete their adolescence properly and grow into secure adults, and the human race as a whole will be able to mature from insecure adolescence to secure adulthood.

In this journey through the stages involved in the development of consciousness that our species progressed, ‘Infantman’ was the ape ancestor who first developed the nurturing training in selflessness that produced the fully cooperative state and, in doing so, liberated consciousness. The various stages of ‘Childman’, who developed from ‘Infantman’, were, as summarised under the picture of the skulls above, the australopithecines who began to experiment with the power of conscious free will: ‘Early Happy Childman’ (Australopithecus afarensis), who evolved into ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’ (Australopithecus africanus), who then developed into ‘Late Naughty Childman’ (Australopithecus boisei). At each stage greater experimentation in conscious self-management was taking place—from demonstrating the power of free will in mid-childhood, to beginning to challenge the instincts for the right to manage events in late childhood.

When the conscious mind broke free of the influence of the instincts and took over management of events, the instincts began to, in effect, resist that takeover, a tension that resulted in the distressing, sobering upset state of the human condition. Indeed, in recognition of a significant change that took place around two million years ago, anthropologists actually changed the name of the genus at that point from Australopithecus to Homo; ‘Childman’, the australopithecines, changed to ‘Adolescentman’, Homo. As stated, adolescence is the stage when the search for identity takes place, and the identity that ‘Adolescentman’, Homo, particularly sought to understand was their lack of ideality—the reason why they were not ideally behaved. Once the march of upset began, its progression could only be brought to an end by finding sufficient knowledge to explain why the instincts’ ‘criticism’ was undeserved. Thus, there was an ever increasing need for mental cleverness to explain ourselves—in particular to find the liberating understanding of the human condition—hence the rapid increase in brain volume from two million years onwards.

After our species entered Adolescence, we necessarily went through the early sobered adolescentman stage (early Homo habilis), to the depressed adolescentman stage (late Homo habilis), through to the adventurous adolescentman stage (Homo erectus, who first left Africa), then to the embattled angry adolescentman stage (Homo sapiens), through to the pseudo idealistic adolescentman stage (Homo sapiens sapiens), through to the hollow adolescentman stage, and now finally, with the finding of understanding of why we have been divisively behaved, humans individually, and humanity collectively, can mature from insecure Adolescence to secure Adulthood: ‘Adolescentman’ becomes TRANSFORMED ‘Adultman’. (Note, ‘man’ is an abbreviation for ‘human’ or ‘humanity’, however, the use of ‘man’ also denotes a recognition that while humanity’s Infancy and Childhood was matriarchal or female-role-led, because that was when nurturing of infants was all-important, humanity’s Adolescence became patriarchal with the emergence of the egocentric, male-role-led need to defy the instincts, search for knowledge and defiantly prove we humans are good and not bad—a transition that will be more fully explained in this presentation. Since humanity’s adulthood will be neither female or male led—because our species’ maturation is complete—‘Adultman’ should more properly be described as ‘Adulthuman’. By the same logic, since Adolescence was originally female role-led, the description should have been Adolescentwoman not Adolescentman, but this is all getting too novel and complicated, so we will leave it all as ‘man’.)

We will now examine these various stages—from the perspective of both the individual and humanity—more closely.