Freedom Expanded: Book 1—The Human Condition Explained

Part 3:8 The anguish of Resignation

The terms ‘Infancy’, ‘Childhood’, ‘Adolescence’ and ‘Adulthood’ are commonly used to describe phases of human maturation, however, having never before been able to explain the battle that humans have been involved in of our conscious intellect against our ignorant instincts, it has not been possible to properly interpret these stages that we as individuals have been going through—and indeed humanity as a whole has traversed—but now we can. What follows then is an explanation of these stages of maturation, in the context of the human condition being understood.

To begin, ‘Infancy’ is the time when consciousness first appears and we become self-aware, able to recognise our existence, become aware of ‘I’. It is not possible to have a sense of self-awareness until such time as the swirling array of experiences steadies enough in our mind, makes sufficient sense to realise that we are at the centre of those changing experiences. It is during ‘infancy’ that we become sufficiently able to understand the relationship between cause and effect to realise that we are at the centre of all the events we are experiencing.

So, the ability to make sense of experience, to understand change sufficiently to be aware or ‘conscious’ of how experiences are related, first demonstrates itself in our infancy when we become self-aware. While some other higher primates are sufficiently able to understand cause and effect to become self-aware, only humans have been able to progress beyond that point and become so able to understand the relationship between events, to make sense of change, that we are able to confidently start manipulating the world around us, which brings about the next stage in the development of conscious thought—childhood.

‘Childhood’ is the stage when humans develop the ability to understand the relationship between cause and effect sufficiently to experiment or ‘play’ with the power of conscious free will. This ability to understand cause and effect meant there was going to come a time when we became sufficiently confident in managing events to carry out experiments in managing events over a brief time and then across increasingly longer periods. Childhood is the ‘Look at me Dad, I can jump puddles!’ stage where we start to confidently manage our lives.

The next stage of ‘Adolescence’ occurs when we become sufficiently adept in our ability to understand cause and effect to want to better understand not just the relationship of events over a brief period of time but over all of time. It is when humans try to make sense of life itself, understand the meaning of all changing events, the meaning of the world we are living in so that we can adjust our lives in accordance with that meaning. Adolescence is when we become philosophical, ‘philosophy’ being ‘the study of the truths underlying all reality’ (Macquarie Dict. 3rd edn, 1998).

It was during this stage of thinking deeply about the meaning of life that we historically encountered the problem of the human condition, the issue of the imperfection of human behaviour generally—and, since we were a product of all the upset that we inevitably encountered during our upbringing, we also tried to understand the upset, the imperfection, the lack of ideality, that was becoming increasingly apparent in our own behaviour.

The problem was that it didn’t take much thinking about what the meaning of existence is before we realised that it is to be cooperative, loving and selfless—a realisation that confronted us with the issue of why aren’t humans cooperative, loving and selfless, which is the issue of the human condition. As was outlined in Part 3:4 and will be more fully introduced in Part 4:4B, the meaning of existence is to develop the order of matter, to integrate matter into ever larger and more stable wholes. While the upset human race has learnt to live in denial of this truth of Integrative Meaning, the fact is, we are surrounded by examples of ordered matter, by arrangements of matter where the parts of the arrangement behave cooperatively. A tree’s leaves, branches, trunk, roots and bark, and indeed all the cells of all those parts of the tree, exist in a state of harmonious cooperation—even behaving selflessly, such as when leaves fall (in effect, give their life) in autumn so that the tree as a whole can better survive through winter. Our body is a similar collection of cooperating parts. Almost everywhere we look we see arrangements of ordered matter and we see how well those arrangements benefit from all their parts cooperating in a selfless fashion. In fact, in the instances where there isn’t such cooperation, such as where we see competition and fighting between organisms, we realise how destabilising and divisive such behaviour is. As such, we deduce very quickly that selfishness and aggression are not consistent with creating order and stability. Moreover, from what we deduce from our surroundings and from what we are taught about the nature of matter at school, we also very quickly realise that there is a tendency of matter to develop ever larger and more stable arrangements of matter; for instance, atoms have come together to form molecules, and in turn molecules have come together to form compounds, which in turn have come together or integrated to form virus-like organisms, which in turn have come together to form single-celled organisms. We are able to observe that single-celled organisms have formed multicellular organisms and, in turn, multicellular organisms have come together or integrated to form societies of multicellular organisms. Clearly there is a hierarchy of ordered matter in the world around us, that ever larger and more stable arrangements of matter are being developed, and that selfless cooperation is the glue that makes those arrangements of matter stay together in a stable state. In essence, we are able to recognise that the meaning of existence is to develop order—to integrate matter into ever larger and more stable wholes. But, as mentioned in Part 3:4, the inherent problem with this obvious truth of Integrative Meaning is that it is unbearably confronting because it begs the question of why do we behave so divisively—so competitively, aggressively and selfishly?

So, when young adolescents realised this obvious truth of Integrative Meaning and the horrifically confronting and unbearably depressing issue it raises of the human condition they soon learnt that, unable to explain it, they had no choice but to resign themselves to living in denial of both the issue itself, and the truth of selfless-cooperation-based Integrative Meaning that confronted them with that issue.

Furthermore, not only have young adolescents been able to reason that the meaning of existence is to be cooperative, loving and selfless, we humans also have unconditionally altruistic instincts—our moral conscience—informing us that is the way we should behave. As was briefly explained in Part 3:4 and will be more fully explained in Part 4:4D, these moral instincts were acquired during a time in our species’ past when our ape ancestors lived in a matriarchal, nurturing, fully cooperative, all-loving, pre-conscious, human-condition-free, upset-free, harmonious, innocent state—a time that is recognised in all our mythologies, such as in the story of the Garden of Eden.

So, from both their own power of reasoning and the ‘voice’ of their own conscience, young adolescents have historically been confronted by the issue of the human condition—the issue of why aren’t we humans ideally behaved now—and the more they tried to think about the question without the explanation of the human condition, the more depressed they became, because the only conclusion they could come to was that humans were a flawed, unworthy, destructive, defiling, bad, awful species. In fact, trying to face down the issue of the human condition, especially the issue of the lack of ideality within yourself, eventually became so depressing—indeed, suicidally depressing—that there was, as mentioned, no option but to resign yourself to adopting a strategy of block-out or avoidance or denial of Integrative Meaning, and of your unbearably condemning cooperative, loving and selfless instinctive self or soul, and with it the whole depressing issue that is raised of your own and the human race’s seemingly immensely flawed condition. Having to resign yourself to blocking out your unbearably condemning, all-sensitive and all-loving instinctive self or soul was a truly terrible decision to have to make, and certainly one adolescents didn’t make easily, because it meant becoming such a false/superficial/fake, empty, effectively dead person, but without the explanation of the human condition there was no other way—the alternative of living in a state of suicidal depression was not an option. The fact that humans have had to resign to living such a horrifically fraudulent and destitute existence is witness to the absolutely extraordinary courage that the human race has exhibited for the last two million years!

This deeper philosophical thought journey that brought humans into contact with the issue of the human condition began when we were around 10 or 11 years of age and deepened until Resignation became unavoidable at about 14 or 15 years of age. In fact, moving children from primary school to secondary school when they were around 12 years old and on the cusp of adolescence was at base a recognition that children had, at this age, undergone this fundamental change from idealistic extravert to sobered introvert.

The final stage of ‘Adulthood’ occurs when humans leave the insecurity of an adolescence spent attempting to understand the meaning of existence, for having succeeded in understanding themselves and their world they are, at last, able to mature to secure adulthood. Since the human race as a whole has not, until now, been able to understand the context, meaning and worth of human life, in particular understand the dilemma of the human condition, humans haven’t been able to properly enter adulthood. That’s not to say that when stages of maturation aren’t properly completed it doesn’t mean subsequent growth stages don’t take place, they do—but if a previous stage isn’t properly fulfilled those subsequent stages are greatly compromised by the incomplete preceding stages. People do grow up, but in a state of arrested development. Without the explanation of the human condition humans have been insecure, they have not properly developed—in fact, they have been preoccupied with still trying to validate themselves, prove that they are good and not bad, find some relief from the insecurity of the human condition. It is only now with understanding of the human condition found that humans will be able to complete their adolescence properly and grow into secure adults, and the human race as a whole will be able to mature from insecure adolescence to secure adulthood. (Incidentally, I initially called our organisation the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood because humanity has been stalled in insecure adolescence searching for the understanding of the human condition that matures humanity to secure adulthood, and since we are presenting that understanding we are laying the Foundation for Humanity’s Adulthood.)

In summary, infancy is ‘I am’, childhood is ‘I can’, adolescence is ‘but who am I?’ and adulthood is ‘I know who I am’.

A much more detailed description of all these stages of maturation will be given shortly in Part 3:11, however, since the Resignation that has been occurring in adolescence is such an important element in understanding our species’ current behaviour it is necessary to provide the following more detailed description of it. (The full description of the process of Resignation appears in the ‘Resignation’ chapter of my book A Species In Denial, which can be accessed at <www.humancondition.com/asid-resignation>.)

______________________

Resignation to living a life of denial of the issue of the human condition and any truths that brought it into focus (which, as we will see as this whole presentation about the human condition unfolds, have been many, many, many truths) has been a feature of human life since our conscious, self-managing mind fully developed some two million years ago and we became sufferers of the agony of the human condition. Indeed, it has been the most important psychological event to occur in human life and yet it has never been explained and only very rarely acknowledged before now. This is because you could not admit to living in denial and at the same time be in denial—you can’t effectively lie if you admit you are lying. To admit to the process of Resignation meant admitting that the resigned adult world was an artificial, superficial, fraudulent, virtually dead world of terrible lies, and to admit that when we couldn’t understand and thus do anything about being so incredibly fake was obviously untenable. It is only now that we can explain—> and thus defend—> and thus leave behind—> and thus ultimately heal the extremely upset, denial-based, alienated world we have been living in that we can afford to admit and talk about all that upset and all the denial and resulting alienation from all that is true and meaningful in our lives. Clearly, an understanding of the process of Resignation is key to understanding why our lives have been so incredibly distressed, lost, empty and weird.

As has been described, the issue of the human condition was first encountered in late childhood. As I will talk more about shortly, having already resigned to living in denial of the issue of the human condition, adults have become highly adept at overlooking the utter wrongness and hypocrisy of human life and blocking out the question it raised as to their own badness/guilt or otherwise, but children in their naivety still recognised that hypocrisy. Children are both able to know (from listening to their instinctive moral conscience) and to reason that the ideal way to behave is to be cooperative, selfless and loving and, as such, are able to recognise that there is something terribly amiss with the way humans are behaving now. They ask, ‘Mum, why do you and Dad argue all the time?’ and ‘Why are we always worried about having enough money?’ and ‘Why are we going to a big, expensive party when the family down the road is so poor?’ and ‘Why is everyone so lonely, unhappy and preoccupied?’ and ‘Why are people so fake; so artificial and false?’ and ‘Why is it that the only thing people talk about when they meet each other is such incredibly superficial things as the weather or the football?’ and ‘What is religion?’ and ‘Why do people go to church?’ and ‘Why do they pray?’ and ‘Who is God?’ and ‘Why do people make awful jokes?’ and ‘why do men kill each other?’ and ‘Why are there wars?’ and ‘Why do we allow pictures of dead people in the paper?’ and ‘Why are there pictures about sex everywhere?’ and ‘Why did those people fly those planes into those buildings?’ And the truth is, these are the real questions about human life, as this quote by the Nobel Prize-winning biologist George Wald acknowledges: ‘The great questions are those an intelligent child asks and, getting no answers, stops asking’ (Introduction by George Wald to The Fitness of the Environment, Lawrence J. Henderson, 1958, p.xvii). The reason children ‘stopped asking’ the real questions—stopped trying to point out the all-important and immensely-obvious-if-you-are-looking-at-the-world-truthfully, yet almost totally unacknowledged proverbial ‘elephant in the living room’ issue of the human condition—was because they eventually realised that adults couldn’t answer their questions; and, more to the point, they were made distinctly uncomfortable by them.

The truth is, the hypocrisy of human behaviour—which is the difference between what our cooperatively-orientated, all-loving, pre-human-condition-afflicted, innocent, original instinctive moral self or soul expects of human behaviour and what our present immensely upset, human-condition-afflicted, denial-committed behaviour is actually like—surrounds us. Two-thirds of the world’s population live in poverty while the rest bathe in material security and continually seek more wealth and luxury. Everywhere there is extreme inequality between individuals, sexes, races and even generations. When a woman pointed out on a radio talk-back program that ‘we can get a man to walk on the moon, but a woman is still not safe walking down the street at night on her own’, she was acknowledging the absurd hypocrisy of human life. Yes, humans can be heartbroken when they lose a loved one, but are also capable of shooting one of their own family. We will dive into raging torrents to help strangers without thought of self, but are also capable of molesting children. We are so loving we will give our life for another and yet we routinely torture others. A community will pool its efforts to save a kitten stranded up a tree and yet humans will ‘eat elaborately prepared dishes featuring endangered animals’ (TIME mag. 8 Apr. 1991). We have been sensitive enough to create the beauty of the Sistine Chapel, yet so insensitive as to pollute our planet to the point of threatening our own existence.

For a child entering adolescence, which has historically occurred around the beginning of their teenage years, this deeper philosophical questioning about the extraordinary inconsistency of human behaviour with what their reasoning and their moral instincts—their mind and their soul—expect of human behaviour leads them to thinking about the inconsistency of their own behaviour with the ideals. So, it was not only the issue of the human condition without—the lack of ideality in the world around them—that has been unbearably depressing for adolescents, it was also the issue of the human condition within, their own lack of ideality from the upset they encountered having to be born into and raised in an upset world.

The result of encountering the issue of the human condition both without and within meant that between the ages of 13 and 15 adolescents struggled to hold on to their innocent, instinctive, born-with awareness of another magic, true, all-loving, utterly cooperative and all-sensitive world free of the human condition. Trying to hold on to the last vestiges of ideality in their lives before they had to resign, young girls, if they were lucky, had their ponies, their last true friend before they died in soul from being used as sex objects, while young boys, if they were lucky, had a dog, their soul’s companion before they undertook their initiation into the war zone of the world of men. (As mentioned, the immensely tragic roles of men and women under the duress of the human condition will be explained in Part 7:1.)

Eventually, however, trying to think about the issue of the human condition both without and within became overwhelming, unbearably—in fact, suicidally—depressing, at which point it became necessary for adolescents to resign themselves to a strategy of living in mental denial of their unbearably condemning instinctive self or soul and the whole depressing issue it raised of the human condition.

Adolescents didn’t resign easily because it meant separating themselves from all the wonder, beauty and excitement of existence that our species’ instinctive self or soul has access to. In fact, denial and the resulting alienation from our true self was a form of death—in resigning you were adopting such a false, dishonest state that you were, in effect, becoming ‘dead’ inside. After Resignation all access to the wonderful world of our species’ soul was going to be blocked out because it raised too many unbearably depressing questions about our current immensely upset, compromised, corrupted life and world. But, by this stage, the ‘voice’ of our conscience was becoming unbearable, leaving us no choice but to repress and ignore it. The English poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744) acknowledged the pain of the criticism emanating from our conscience when he wrote, ‘our nature [our primary instinctive state, which is our cooperatively orientated moral soul, the voice of which is our conscience—is]…A sharp accuser, but a helpless friend!’ (An Essay on Man, Epistle II, 1733). His compatriot, the poet laureate William Wordsworth (1770-1850), was also pointing out the unbearable condemnation from our instinctive conscience when, in his great poem Intimations of Immortality, he wrote about our ‘High instincts before which our mortal Nature / Did tremble like a guilty thing surprised.’ And the exceptionally honest French Algerian author, philosopher and Nobel Prize winner for Literature, Albert Camus (1913-1960), was similarly voicing the murderous pain of the criticism coming from our naive, ignorant, innocent instinctive self when he wrote, ‘[can] innocence, the moment it begins to act…avoid committing murder [?]’ (L’Homme Révolté, 1951, [pub. in English as The Rebel, 1953]).

And so, struggling mightily to resist Resignation, adolescents typically locked themselves in their room and surrounded themselves with loud, head-banging music, just trying to lose themselves, escape the pain of what they were thinking and feeling about the wrongness of the world and of their own imperfections—and about the terrible, deadening consequences of giving in and resigning themselves to blocking out their soul and stopping themselves from thinking about anything that brought the issue into focus, which is, of course, nearly everything.

Yes, Resignation brought with it both denial of soul (soul-repression, soul-death or ‘psychosis’) and fear of thinking (the inability to think, conscious denials or ‘neurosis’). Revealingly, ‘psychosis’ literally means ‘soul-illness’, derived as it is from psyche, which according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary comes from the Greek word psukhe meaning ‘breath, life, soul’, and which, according to The Encyclopedic World Dictionary, ‘Homer identified with life itself’ (and ‘Plato as immortal and akin to the gods’ and ‘neoplatonism as the animating principle of the body’), and osis which, according to Dictionary.com, is of Greek origin and means ‘abnormal state or condition’. ‘Neurosis’ similarly means ‘nerve-illness’, derived as it is, according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary, from the Greek word neuro meaning ‘neuron or nerve’, and osis which, as just mentioned, means ‘abnormal state or condition’. Thus, the two elements involved in producing the upset state of the human condition of our gene-based instinctive soul and our newer nerve-based fully conscious thinking mind both suffered when humans resigned. In essence, we died in soul and in mind, we killed off our instinctive self or soul and we stopped using our conscious mind to think truthfully and thus effectively—what an extraordinarily high price to have to pay!

(Just to complete the description-by-definition of our soul-and-mind-destroyed upset state and the psychological healing of our upset state that understanding of the human condition finally makes possible, the word ‘psychiatry’—a discipline that can now finally be practiced in earnest—literally means ‘soul-healing’, coming as it does from psyche, the meaning and source of which has already been described, and the Greek word iatreia, which, according to The Encyclopedic World Dictionary, means ‘healing’. Similarly, ‘psychology’, which literally means the ‘study of the soul’, derived as it is, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, from psyche, meaning ‘soul’, and the Greek word logia meaning ‘study of’, is another field that can now, at last, be truthfully and thus properly studied. Also, while talking about these two elements of our gene-based instinctive self or soul and our newer nerve-based fully conscious thinking mind, I should point out that our instinctive self or soul did involve natural selection of nerves or neural pathways, so there was some nerve-based refinement involved in our gene-based instinctive self or soul, and similarly, our newer nerve-based fully conscious thinking mind did also develop by the gene-based process of natural selection, so our newer nerve-based fully conscious thinking mind also involved some gene-based natural selection. While I seem to talk about our gene-based instinctive self as being distinct or separate from our nerve-based conscious thinking self, there was obviously some of the two information refinement systems involved in each of the two conflicting aspects of ourselves. In a way there is some ‘mind’ involved in our ‘soul’, and some ‘instincts’ involved in our ‘intellect’. Some definitions of ‘psyche’ have referred to it as ‘the human soul, spirit or mind’, and this acknowledgement of some ‘mind’ involved in our ‘soul’ is not inaccurate.)

Tragically, because of our soul’s unbearable criticism, upset humans have been ruthlessly repressing that idealistic part of themselves and, in the process, repressing all the beauty and truth that our soul knows of and has access to—to such an extent that resigned humans have now lost almost all memory of that original, innocent, ideal, true world that our species grew up in. And without that memory humans walk in meaningless darkness. The word ‘enthusiasm’ is derived from the Greek word enthios, which means ‘God within’. Without some knowledge of the heavenly, integrative, unconditionally loving state that our soul has already experienced, without some knowledge of ‘the God within’, life lost its richness and value. Resignation to a life of living in denial of the issue of the human condition came at a very high price indeed.

Since we can now understand why such extreme alienation emerged in us humans, it is worth including here the following incredibly honest collection of quotes from the great Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing (1927-1989), who bravely defied the tradition of denial when he wrote that ‘Our alienation goes to the roots. The realization of this is the essential springboard for any serious reflection on any aspect of present inter-human life…We are born into a world where alienation awaits us. We are potentially men, but are in an alienated state [p.12 of 156] …the ordinary person is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be. As adults, we have forgotten most of our childhood, not only its contents but its flavour; as men of the world, we hardly know of the existence of the inner world [p.22] …The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man [p.24] …between us and It [our true self or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete. Deus absconditus. Or we have absconded [p.118] …The outer divorced from any illumination from the inner is in a state of darkness. We are in an age of darkness. The state of outer darkness is a state of sin—i.e. alienation or estrangement from the inner light [p.116]’ …We are all murderers and prostitutes—no matter to what culture, society, class, nation one belongs…We are bemused and crazed creatures, strangers to our true selves, to one another, and to the spiritual and material world [pp.11-12]’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967). ‘We are dead, but think we are alive. We are asleep, but think we are awake. We are dreaming, but take our dreams to be reality. We are the halt, lame, blind, deaf, the sick. But we are doubly unconscious. We are so ill that we no longer feel ill, as in many terminal illnesses. We are mad, but have no insight [into the fact of our madness]’ (Self and Others, 1961, p.38 of 192).

It is no wonder adolescents fought so hard to resist Resignation! Indeed, if we need any further proof of the struggles faced by resigning teenagers, consider the agonising poems that adolescents in the throes of Resignation quite often wrote as one way of expressing their great struggle to someone—if only on a piece of paper—because adults, who were already resigned to living in denial of the whole issue of the human condition, were unable to recall and empathise with what they were going through. The following is an example of such a poem. Sent to the WTM in February 2000 by Fiona Miller after she read my first book Free: The End Of The Human Condition, it fully expresses the torture of accepting the consequences of Resignation that Laing so honestly described, namely the death of our soul’s true world and the adoption of a false, all-but-dead, deluded, alienated world. Significantly, it was accompanied by a note that also illustrates the fact that once resigned, adolescents typically (like all resigned adults before them) very quickly forget or, more specifically, block-out the whole horrific episode: ‘I dug out this poem I wrote in my diary when I was about 13 or 14 years old…It has always sounded very depressing to me whenever I have read it and so I have not shown anyone since leaving school…Maybe this was the “transition point” [a term I had used about Resignation in writings I had given Fiona] for me when instead of trying to fight forever I just integrated very nicely!!??’

This is Fiona’s incredible Resignation poem: ‘You will never have a home again / You’ll forget the bonds of family and family will become just family / Smiles will never bloom from your heart again, but be fake and you will speak fake words to fake people from your fake soul / What you do today you will do tomorrow and what you do tomorrow you will do for the rest of your life / From now on pressure, stress, pain and the past can never be forgotten / You have no heart or soul and there are no good memories / Your mind and thoughts rule your body that will hold all things inside it; bottled up, now impossible to be released / You are fake, you will be fake, you will be a supreme actor of happiness but never be happy / Time, joy and freedom will hardly come your way and never last as you well know / Others’ lives and the dreams of things that you can never have or be part of, will keep you alive / You will become like the rest of the world—a divine actor, trying to hide and suppress your fate, pretending it doesn’t exist / There is only one way to escape society and the world you help build, but that is impossible, for no one can ever become a baby again / Instead you spend the rest of life trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze.’ (Other incredibly honest poems are included in the aforementioned ‘Resignation’ chapter in A Species In Denial at <www.humancondition.com/asid-resignation>.)

Fiona was right, stopping thinking truthfully meant condemning yourself to a life ‘trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze’. The fact is, Resignation was a state of extremely prejudiced falseness and thus futility when it came to thinking effectively. The resigned state is not interested in the truth, it is interested only in evading the truth. As the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) recognised, ‘The discovery of truth is prevented most effectively…by prejudice, which…stands in the path of truth and is then like a contrary wind driving a ship away from land’ (Essays and Aphorisms, tr. R.J. Hollingdale, 1970, p.120 of 237). Aldous Huxley, who was introduced earlier, also courageously recognised why the resigned mind is incapable of penetrating thought when he wrote, ‘We don’t know because we don’t want to know’ (Ends and Means, 1937, p.270). T.S. Eliot was also acknowledging this truth when he wrote that ‘human kind cannot bear very much reality’ (Burnt Norton, 1936).

But while the consequences of Resignation were horrific, the alternative of continuing to try to think truthfully was an even worse option, as the Australian comedian Rod Quantock once said, ‘Thinking can get you into terrible downwards spirals of doubt’ (‘Sayings of the Week’, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 1986); and Albert Camus wrote that ‘Beginning to think is beginning to be undermined’ (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1942); and another Nobel Prize winner for literature, Bertrand Russell, similarly said, ‘Many people would sooner die than think’ (Antony Flew, Thinking About Thinking, 1975, p.5 of 127).

So yes, going through Resignation has been a truly horrific experience. A friend and I were walking in bushland past a school one day when we came across a boy, who would have been about 14 years old, sitting by the track in an hunched, foetal position. When I asked him if he was okay he looked up with such deep despair in his eyes that it was clear he didn’t want to be disturbed and so we left him alone. It was very apparent that he was trying to wrestle with the issue of the human condition, but without understanding of the human condition it hasn’t been possible for humans to do so without becoming so hideously condemned and thus depressed that they had no choice but to eventually surrender and take up denial of the issue of the human condition as the only way to cope with it—even though doing so meant adopting a completely dishonest and superficial, effectively dead, existence.

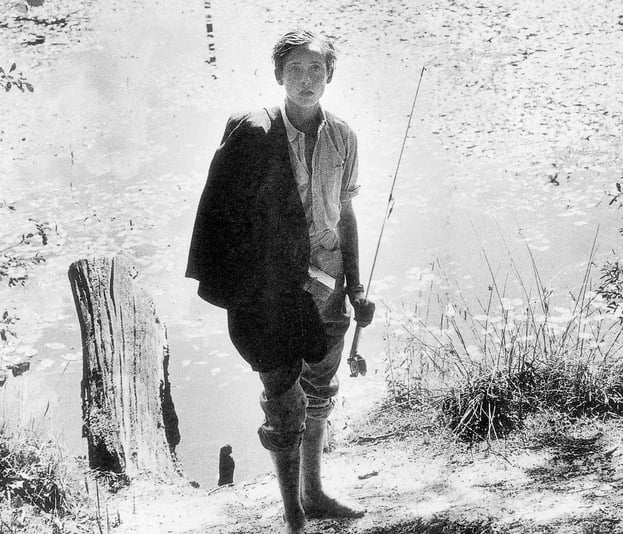

I haven’t as yet come across a photograph of an adolescent in the midst of Resignation, however, in my picture collection I do have the following haunting image of a boy who had, the previous day, lost all his classmates in a plane crash, and his expression is exactly the same deeply sobered, drained pale, all-pretences-and-facades-stripped-away, pained, tragic, stunned, human-condition-laid-bare expression I have seen on the faces of adolescents going through Resignation. We can see in this boy’s face that all the artificialities of human life have been rendered meaningless and ineffectual by the horror of losing all his friends, leaving bare only the sad, painful awareness of a world devoid of any real love or truth.

‘Too poor to go on school trip, boy fishes the day after classmates perish in plane crash’

Photo by Harry Benson; published in the Fall Special 1991 edition of LIFE magazine

As mentioned above, one of the greatest agonies for resigning adolescents was that the whole adult world, having already resigned themselves, could not acknowledge the Resignation process and only rarely recall having gone through it, which meant adolescents were essentially alone in what they were going through. Tragically there has been virtually no dialogue between resigning adolescents and resigned adults. Indeed, when adults read the ‘Resignation’ chapter in my book A Species In Denial they typically feel unnerved because in doing so they are prompted to remember being there, they are awakened to the memory of having made that terrible transition to the resigned state. Remember, it was only on very rare occasions that adults even acknowledged the existence of the issue of the human condition, let alone having been through Resignation—which makes the following acknowledgements very special indeed.

In his 1996 book The Moral Intelligence of Children, the renowned child psychiatrist Robert Coles provided a rare account by an adult of a teenager in the midst of Resignation. Coles is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, which is not surprising given the degree of honesty he managed to get up in this book about what adolescents go through—it is a fact that a little bit of truth has been lauded while a lot of truth has been loathed. In commencing his recollection, Coles wrote: ‘I tell of the loneliness many young people feel, even if they have a good number of friends…It’s a loneliness that has to do with a self-imposed judgment of sorts: I am pushed and pulled by an array of urges, yearnings, worries, fears, that I can’t share with anyone, really.’ As emphasised, it has been difficult enough for adolescents to look at the human condition without, namely the imperfection of the world around them, but it is when they looked at the human condition within themselves that they became overwhelmed with depression. The fact is, no child has received the amount of nurturing all children received before the upset state of the human condition emerged, and when this upset within adolescents became apparent it did result in a ‘self-imposed judgment’. Coles went on to describe his encounter with the teenager and the effect of this judgment of self that adolescents typically experienced: ‘This sense of utter difference…makes for a certain moodiness well known among adolescents, who are, after all, constantly trying to figure out exactly how they ought to and might live…I remember…a young man of fifteen who engaged in light banter, only to shut down, shake his head, refuse to talk at all when his own life and troubles became the subject at hand. He had stopped going to school, begun using large amounts of pot; he sat in his room for hours listening to rock music, the door closed. To myself I called him a host of psychiatric names: withdrawn, depressed, possibly psychotic; finally I asked him about his head-shaking behavior: I wondered whom he was thereby addressing. He replied: “No one.” I hesitated, gulped a bit as I took a chance: “Not yourself?” He looked right at me now in a sustained stare, for the first time. “Why do you say that?” [he asked]…I decided not to answer the question in the manner that I was trained [as a denial-complying psychiatrist] to reply…an account of what I had surmised about him, what I thought was happening inside him…Instead, with some unease…I heard myself saying this: “I’ve been there; I remember being there—remember when I felt I couldn’t say a word to anyone”…I can still remember those words, still remember feeling that I ought not to have spoken them: it was a breach in “technique”. The young man kept staring at me, didn’t speak, at least with his mouth. When he took out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes, I realized they had begun to fill’ (pp.143-144 of 218).

The boy was in tears because Coles had reached him with some recognition and acknowledgement of what he was wrestling with. Coles had shown some honesty about what the boy could see and was struggling with, namely the horror of the utter hypocrisy of human behaviour—which all those who had already resigned to living in denial of the human condition had determinedly committed their minds to avoiding. It has been very hard to grow up in a world that is so full of bullshit/denial/dishonesty, most especially its silence about the truth of the human condition.

The words Coles used in his admission that he too had once grappled with the issue of the human condition, ‘I’ve been there’, are exactly those used by one of Australia’s greatest poets, Henry Lawson, in his exceptionally honest poem about the human condition, about the unbearable depression that has resulted from trying to confront the question of why human behaviour is so at odds with the cooperative, loving Godly ideals of life. In his 1897 poem The Voice from Over Yonder Lawson wrote: ‘“Say it! think it, if you dare! / Have you ever thought or wondered / Why the Man and God were sundered [torn apart]? / Do you think the Maker blundered?” [Do you think humans are evil and a mistake?] / And the voice in mocking accents, answered only: “I’ve been there.”’ The unsaid words in the final phrase, ‘I’ve been there’, are ‘and I’m not going there again!’—the ‘there’ and the ‘over yonder’ of the title being the state of deepest, darkest depression.

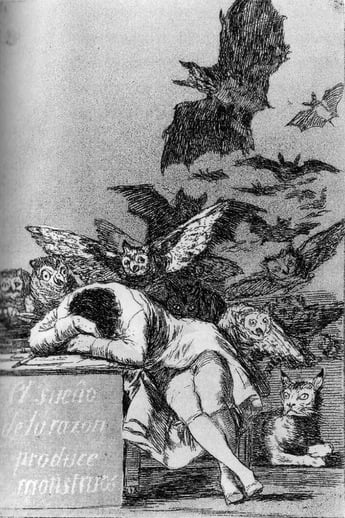

Interestingly, in his best-selling 2003 book Goya, about the great Spanish artist Francisco Goya, the Australian Robert Hughes, who for many years was TIME magazine’s art critic, described how he ‘had been thinking about Goya…[since] I was a high school student in Australia…[with] the first work of art I ever bought…[being] a poor second state of Capricho 43…The sleep of reason brings forth monsters… [Goya’s most famous etching reproduced above] of the intellectual beset with doubts and night terrors, slumped on his desk with owls gyring around his poor perplexed head…And I [then] got to know him a little better, through reproductions in books…all those decades ago…[when I was] fourteen.’ Hughes then commented that, ‘glimpsing The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was a fluke’ (pp.3, 4). A little further on, Hughes wrote of this experience that ‘At fifteen, to find this voice [of Goya’s]—so finely wrought [in The sleep of reason brings forth monsters] and yet so raw, public and yet strangely private—speaking to me with such insistence and urgency…was no small thing. It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it’ (p.5). Again, while the process of Resignation is such a horrific experience that adolescents determined never to revisit it, or even recall it, Hughes’ attraction to The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was not the ‘fluke’ he thought it was. The person slumped at the table with owls and bats gyrating around his head perfectly depicts the bottomless depression that occurs in humans just prior to resigning to a life of denial of the issue of the human condition, and someone in that situation would have recognised that meaning instantly, almost wilfully drawing such a perfect representation of their state out of the world around them. Even the title is accurate: ‘The sleep of reason’—namely reasoning at a very deep level—does ‘bring forth monsters’; what did the comedian Rod Quantock say? ‘Thinking can get you into terrible downwards spirals of doubt’! While Hughes hasn’t recognised that what he was negotiating ‘At fifteen’ was Resignation, he has accurately recalled how strong his recognition was of what was being portrayed in the etching: ‘It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it.’ Hughes’ words, ‘I have been through it’, are almost identical to Coles and Lawson’s words ‘I’ve been there.’

Carl Jung gave this deadly accurate description of the human condition: ‘When it [our shadow] appears…it is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience for him to gaze into the face of absolute evil’ (Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, 1959, tr. R.F.C. Hull; in The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 9/2, p.10). Yes, it was ‘a rare and shattering experience’ for resigned adults to allow their minds to confront the question of why their behaviour is so diabolically at odds with what soulful, cooperative ideal behaviour would be like—despite it being the stark staring obvious question that had to be addressed and explained if we humans were to ever understand ourselves.

In Part 2:3 I also included Olive Schreiner’s extraordinarily honest recollection, on her death bed, of having grappled with the issue of the human condition as a child—when in her ‘darkest hour’ she ‘tried to wear no blinkers…tried to look nakedly in the face those facts which make most against all hope’. Those ‘facts’ being the ones that caused her to exclaim, ‘All the world seemed wrong to me…Why did everyone press on everyone and try to make them do what they wanted? Why did the strong always crush the weak? Why did we hate and kill and torture? Why was it all as it was? Why had the world ever been made?’

These are rare acknowledgements by adults of Resignation, because on the whole the resigned adult world has been incapable of speaking the truth to resigning adolescents. If I was to give this talk to young people aged between 12 and 14 years of age they would hear what I had to say clearly because they have not yet resigned to a life of denial of truth. Older adolescents who have already resigned just talk bullshit—saying such things as, ‘You’ve got to go out and buy yourself the latest gear, get yourself lost at parties, just escape, rave on and rage’; just get distracted because ‘There are no answers to those questions you are wrestling with, so give up trying to think about them.’ (Note, it is a measure of the extent of the denial in the world that there is no everyday word for all the denial that resigned humans practice, except for the swear words ‘bullshit’ or ‘crap’.)

For their part, parents did the best they could from their resigned position. Mothers gave their troubled adolescent a hug and uttered such empty reassurances as ‘Sweetheart, you’ll be alright, you know the world is just the way it is’, while fathers typically turned their backs because being so egocentric men especially didn’t want to be reminded of a lost innocent state and the issue it raised of the human condition. So, locked in their room playing loud, head-banging music to try to stop the pain in their brain and with nobody to talk to truthfully, the adolescent was dying inside—their desire to think and their true self or soul was dying.

The response from the larger world in general to the honest questioning of children and to the agony of young adolescents struggling with the horrific imperfection of human life was to say something in keeping with the tradition of denial, like, ‘It’s just our animal instincts to be brutally aggressive, mean and selfish, it’s not a perfect world, you’ll get over it.’ But adolescents, who hadn’t yet adopted all the lies, knew full well that the way humans behave now is not the way humans should or once did behave—they did not buy the false excuses sprouted by mechanistic science. Their truthful mind and truthful instinctive moral soul was still alive inside of them and the way humans behave now simply terrorised them. For those who are already resigned and living in denial it is self-evident why everyone is lying and being so silent about the incredible wrongness of human behaviour, but to unresigned innocents it has been an extraordinary and inexplicable mystery.

From the young adolescent’s point of view, adults have been ‘full of shit’; full of denial; using all manner of false excuses and not even admitting that there is a very real and serious problem with human behaviour. Resigned adults certainly didn’t admit that humans once lived in an upset-free, innocent state because by not admitting that they were eliminating the possibility in their mind of there being any basis for any question that needed to be asked about present human behaviour. And it is only adults who have resigned to living in denial of the issue of the human condition who advance the argument that our current aggressive nature is due to savage animal instincts in us and, as such, that there is no fundamental dilemma or underlying psychosis and neurosis involved in human behaviour—that there is no issue of the human condition to have to be explained. Resigned adults also denied there was any integrative, cooperative meaning and purpose to existence, maintaining instead that change is random. The resigned adult world has been ‘God-fearing’ not ‘God-confronting’, but those who are unresigned know these excuses are completely false.

So how then have resigned adults rationalised the agonies that adolescents have been going through during Resignation? Unable to talk about the Resignation that has taken place in the lives of humans when they were teenagers, resigned, denial-complying, mechanistic, reductionist scientists simply blamed the well known struggles of adolescence on the hormonal upheaval that accompanies puberty, the so-called ‘puberty blues’—even terming glandular fever, a debilitating illness which often occurs in mid-adolescence, a puberty-related ‘kissing disease’. These terms, ‘puberty blues’ and ‘kissing disease’, are dishonest, denial-complying, evasive excuses because it wasn’t the onset of puberty that was causing the depressing ‘blues’ or glandular fever, but the trauma of Resignation, of having to accept the death of your true self or soul. For glandular fever to occur a person’s immune system must be extremely rundown, and yet during puberty the body is physically at its peak in terms of growth and vitality—so for an adolescent to succumb to the illness they must be under extraordinary psychological pressure, experiencing stresses much greater than those that could possibly be associated with the physical adjustments to puberty, an adjustment that, after all, has been going on since animals first became sexual. The depression and glandular fever experienced by young adolescents are a direct result of the trauma of having to resign to never again revisiting the subject of the human condition.

Of course, when adolescents encountered the extreme depression that thinking about the human condition could cause, they very quickly appreciated why adults were using all this bullshit, all these denials to cope, because they too certainly never wanted to experience that suicidal depression ever again. Once people resigned it was almost impossible to get them to think about the issue of the human condition again, which is why people go ‘deaf’ reading my books. This ‘deaf effect’, where people find it difficult absorbing discussion about the human condition, is a very real phenomenon. Resignation, when adolescents take up the strategy of living in denial of the human condition, has been a watershed moment in people’s lives and yet it has never been discussed because to admit that you have taken up lying would make that strategy of lying unbearable and untenable.

Before finishing this long but necessary description of Resignation, I need to describe an adolescent’s transition from the pre-resigned situation, where they expect behaviour to be cooperative and loving, to the post-resigned state, where they embrace an extremely competitive, aggressive and selfish existence. It is an absolutely astonishing shift in behaviour, but if we follow closely what happens in the mind of resigning adolescents we can appreciate why and how such a transition takes place.

As has now been explained, what upset humans did when they unsuccessfully attempted to confront the issue of the human condition—that is, when they unsuccessfully attempted to understand why humans aren’t behaving ‘properly’ (which is in the way that our moral instincts expect human behaviour to be like)—was that they resigned themselves to blocking out the whole issue. But having given up on trying to understand the human condition they were then left needing to find some way of feeling good about themselves. At this point the post-resigned mind set about seeking any reinforcement it could find; it became focused on seeking ways to at least relieve the insecurity it was having to live with, the feeling that it wasn’t ideal, good. The post-resigned human became focused on seeking all manner of power, fame, fortune and glory as their only means of relieving themselves of the agony of the human condition. In short, they became extremely egocentric, their minds became focused or ‘centred’ on making their ego, which the dictionary defines as ‘the conscious thinking self’, feel good and not bad—‘Okay, I can’t explain why I am not and the world is not ideally behaved, so I’ll give up on that, but that leaves me feeling bad about myself, feeling that I’m not a good person, so how am I going to live with that? I know, I’ll go out and get as much power, fame, fortune and glory as I can and then I will at least feel a little bit better about myself.’ And that is what happened—pre-resigned humans are idealistic and truthful, while post-resigned humans are materialistic, evasive, dishonest, superficial, self-centred, ego-centric power-fame-fortune-and-glory-seekers. And with each resigned person seeking to achieve as much power, fame, fortune and glory as they could, every opportunity to achieve power, fame, fortune and glory became highly contested, the result being that resigned adults became extremely competitive. It can be seen that this competition has nothing to do with the sort of competition instinct-controlled animals practice with their incessant rivalry over food, shelter, space and a mate, even though that has been the excuse used to explain away our extremely competitive natures. Our competitive natures arise from the insecurity we suffer from of the human condition, it is psychologically derived.

To draw on the Adam Stork analogy, when Adam set out in search of knowledge and encountered the undeserved criticism from his instinctive self of that search, in order to cope he had no choice but to resign himself to living a life of attacking the criticism, of trying to relieve himself of the criticism by winning as much power, fame, fortune and glory as he could find, and to blocking out the criticism. He became angry, egocentric and alienated—in a word, upset. Adam Stork then had a son or daughter who had to grow up in an upset world, which meant Adam Stork Junior was going to be a product of both the upset from his or her own searching for knowledge and also the effect upon him or her of the upset accumulated by the previous generation. We can see that resigning to a life of anger, of competitive egocentricity, and of alienation began when the search for knowledge began, however, as upset accumulated and increased over generations so too did the degree of condemnation for being increasingly non-ideally behaved, and thus the depth of depression prior to Resignation became worse and worse, and thus the commitment after Resignation to never again revisiting the issue of the human condition became greater and greater—to the point we are at today, where upset is extreme, Resignation is a terrifying experience and the commitment to not engaging the subject of the human condition is immense; which again is why it is initially very difficult for people today to absorb or take in or ‘hear’ discussion of the human condition. Even the word ‘human condition’ leaves humans today in deep shock—despite recent attempts by scientists like E.O. Wilson to nullify the term’s profundity (as will be discussed in detail in Part 4:12I).

A further stage that occurred after resigning to a life of seeking relief from the insecurity caused by the human condition through winning power, fame, fortune and glory was to become, as we say, ‘born-again’ to the soul’s ideal world. After living a false, seemingly meaningless and destructive existence for many years, resigned adults could become so disenchanted with their life that they could decide to abandon that way of living and take up support of some form of idealism. They could become ‘born-again’ to religion, to supporting left-wing politics, to being dedicated environmentalists, feminists, activists for the rights of indigenous people, or animal liberationists. These were pseudo forms of idealism because real idealism depended on defying and ultimately defeating, through understanding, the unjustly condemning idealism of the world of the soul, not on caving-in to it. To use the Adam Stork analogy, at any time Adam could quit the upsetting battle to find knowledge and fly back on course, give in to his instincts, but in doing so he would no longer be participating in the heroic search for knowledge.

It is true that the battle to defy and defeat ignorance was corrupting and when people became overly corrupt they had to give up fighting ignorance and try and bring some soul and its world of truth and soundness back into their lives. For those who had become overly corrupted, excessively angry and destructive, the adoption of a born-again, pseudo-idealistic strategy was a responsible reaction. The problem was, however, that unable to explain and thus confront and admit their extremely corrupted and alienated state, they were using the born-again-to-‘idealism’ lifestyle to delude themselves that what they were doing was actually right, that it was ideal. They deluded themselves that they held the ‘moral high ground’ when the opposite was true. They even used their born-again lifestyle to delude themselves that they were uncorrupted people. There was an extremely deluded, selfish aspect to their behaviour—a desire to, as their critics said, ‘feel-good’ about themselves. The truth is the born-again state was the most dishonest and alienated state humans could adopt. Much more will be said about the immense danger of the delusion involved in pseudo idealism in Part 3:11E, and also in Part 3:11H, ‘The final 200 years when pseudo idealism took humanity to a death-by-dogma, end play state of terminal alienation—the time when we needed to, as the Bible warned, “beware of false prophets”, the merchants of delusion and denial, for they are “the abomination that causes desolation”.’

As will be explained more fully in Part 3:11G, the great value of religions, compared to other forms of pseudo idealism, was that they involved a high degree of honesty, a significant acknowledgment of the alienated state. This honesty was contained in the sound life and words of the prophet around whom the religion was founded, because through acknowledging the prophet and his denial-free life and thoughts, a person’s own lack of honesty and soundness was also being acknowledged, albeit indirectly. And yet, the problem with religions, and why in recent times they have waned in popularity, was precisely this honesty, for the more alienated people became, the less confronting honesty they could bear. Born-again’ers needed more guilt-free forms of idealism to support, as this quote, which has been mentioned previously, acknowledges: ‘The environment became the last best cause, the ultimate guilt-free issue.’

So while resigned people who were not born-again to ‘idealism’ were living a false existence, they were at least still participating in humanity’s heroic battle to defy the soul’s ignorance as to the true goodness or worthiness of humans. They were ‘bullshitting’, living dishonestly, but those who had effectively quit the all-important battle—and who had not only quit it but were now effectively subverting it—whilst pretending to be ideal were ‘double bullshitters’, doubly dishonest. With understanding of the human condition it is not hard to understand what has been referred to as ‘right-wing prejudice’ against ‘idealism’. At a certain point the lies became suffocating, unbearable—especially the lie that humans’ lack of ideality meant they were evil, inferior and worthless, but most specifically the lie that people practicing born-again ‘idealism’ were themselves ideal.

Overall, we can see that only the finding of understanding of the human condition could unravel this terrible mess, in particular end the need for the relief of power, fame fortune and glory and all the destructive materialistic greed, egocentricity and competition that resulted from it, and end the immensely dishonest and extremely dangerous practice of pseudo idealism.

And, most wonderfully, with understanding of the human condition now found we can at last tell young adolescents the truth about the extremely upset world we live in, we can explain the incredible imperfection of human life. We can end the great and terrible (‘terrible’ from an innocent’s point of view) silence/denial/lie about the upset, immensely corrupted and alienated human condition. And we can tell the more innocent races, like the Bushman of the Kalahari, the Australian Aborigines and the Amazonian Indians, what has actually been going on—that people in the ‘developed’ world are not the seemingly secure and confident people they portray themselves as, but in fact sad, alienated lost souls. Imagine how much that honesty is going to help the unresigned and the relatively innocent. Imagine their enormous relief when finally told the compassionate truth about the extraordinarily corrupted human condition and the good reason why humans have been that way. It means children will no longer have to resign themselves to a life of mental denial of their soul’s true world and adopt all the escapist ego-centric, materialistic, self-centred, selfish preoccupations of resigned adults today. And it means those more innocent amongst us will no longer be intimidated, seduced and overwhelmed by the deluded arrogance and pretence of the extremely alienated world. To properly help relatively innocent races like the Australian Aborigines we had to stop talking pseudo idealistic drivel to them, telling them in condescending tones that they were good at finding ‘bush tucker’ and how important ‘country’ is to them and how ‘sorry’ we are for taking their country, and start telling them the truth about how corrupted we are and how relatively uncorrupted they are. Typically, it was the most corrupted who went on with the most drivel because taking up the cause of Aborigines made them feel good about themselves—it made them feel as though they weren’t corrupted. In other words, they were using the ‘plight’ of the Aborigines as a way to avoid being honest about their own plight, their own condition, when it was precisely that dishonesty that they were adding to with their pseudo idealistic behaviour that was so destructive of Aborigines in the first place! Instead of being selfless and considerate of others, as they maintained they were being, they were being selfish; they were using Aborigines to artificially relieve themselves of their own corrupted condition, not help Aborigines as they claimed. They were actually doing the complete opposite of helping the Aborigines because, again, it was precisely their lying (which they were adding to by the minute with what they were doing) that was so destructive of the Aborigines’ relative innocence. As mentioned, much more will be said about the horror and danger of pseudo idealism shortly in Parts 3:11E and 3:11H.

In short, what destroyed the innocent was not so much what was done to them, destructive as that often was, but the lying to them about ourselves, about our own upset human condition. So the truth not only sets upset humans free, it also liberates the more innocent looking on. I consider Sir Laurens van der Post to be the pre-eminent philosopher of the twentieth century, so I would like to include here his thoughts on the immensely destructive codependent (which means ‘reliant on another to the extent that independent action is no longer possible’ (Macquarie Dict. 3rd edn, 1998)) effect that the lies of the resigned world have had on those still relatively innocent: ‘Nor should we forget that there were races in the world which vanished not because of the wars we waged against them but simply because contact with us was more than their simple natural spirit could endure’ (The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955, p.101 of 159), and, ‘mere contact with twentieth-century life seemed lethal to the Bushman. He was essentially so innocent and natural a person that he had only to come near us for a sort of radioactive fall-out from our unnatural world to produce a fatal leukaemia in his spirit’ (The Heart of the Hunter, 1961, p.111 of 233), and, ‘Only the irrepressible gaiety of the Bushman of old was missing in him. Knowing what contact with Europeans has done to aboriginal laughter in Africa, I had no right to be surprised. Indeed I have lived with primitive people so much that I have an inkling now of the almost paralytic effect our mere presence can have on their natural spirit. It is as if, when they first encounter us, the independence of our minds from instinct [namely our alienation] and our immense power in the physical world, which to them is not composed of inanimate matter but is another manifestation of master spirits, trap them into the belief that we are gods of a sort…If only we were humble enough to realize that just by what we are we play the devil with the natural spirit of man’ (ibid. p. 56). And at last the human race can afford to be ‘humble enough’ to stop ‘play[ing] the devil with the natural spirit of man’—and before long this ability to be honest about our lives will allow generations of humans to appear who won’t have experienced an upset childhood, out of which will eventually emerge a human race that is entirely free of the human condition.

Another aspect of human behaviour post-Resignation is that those who were resigned tended to assume it was self-evident to everyone else why they were behaving so outrageously arrogantly, deludedly and dishonestly, but, again, if resigned adults wouldn’t admit why they were behaving in a way that was so different to what our innocent instinctive self or soul expected, then the unresigned or relatively innocent could have no possible way of knowing why they were behaving so extraordinarily. One of Carl Jung’s most gifted students, the Austrian psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957), was another who wrote honestly about the codependent effect that the lies of the resigned world have had upon cooperative, loving, trusting, soul-infused innocence when he described how ‘The living [those relatively free of upset]…is naively kindly…It assumes that the fellow human also follows the laws of the living and is kindly, helpful and giving. As long as there is the emotional plague [the flood of extreme upset in the world], this natural basic attitude, that of the healthy child or the primitive…[is subject to] the greatest danger…For the plague individual also ascribes to his fellow beings the characteristics of his own thinking and acting. The kindly individual believes that all people are kindly and act accordingly. The plague individual believes that all people lie, swindle, steal and crave power. Clearly, then, the living is at a disadvantage and in danger’ (Listen, Little Man!, 1948, p.8 of 109).

In concluding this Part, it needs to be emphasised that although the resigned adult lived a soul-destroyed, materialistic, evasive, dishonest, superficial, self-centred, arrogant, ego-centric power-fame-fortune-and-glory-seeking life, that horrible ‘plague’ existence has, until now, been an unavoidable, in fact absolutely necessary, way of living. The alternative of facing the human condition, without understanding of it, was impossible. The situation has been that if upset humans were to carry on and continue their heroic search for knowledge, ultimately for the liberating understanding of the human condition, then they had to resign themselves to living under the horrible duress of that condition. The courage of the human race, which is the subject of the next Part, has been absolutely incredible.

Yes, having to resign and live in a state of extreme dishonesty was immensely heroic, but thank goodness Resignation no longer has to occur. That classic of American literature, J.D. Salinger’s 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye, is all about a 16-year-old boy struggling against having to resign. The boy, Holden Caulfield, felt ‘surrounded by phonies’ (p.12 of 192), in a world ‘full of phonies’ (pp.118 & 151) and ‘morons’ who ‘never want to discuss anything’ (p.39), of living on the ‘opposite sides of the pole’ (p.13) to most people, and in a situation where he absolutely ‘hate[d]’ ‘school’ (p.117), a time when he ‘just didn’t like anything that was happening’ (p.152), to wanting to escape to ‘somewhere with a brook…[where] I could chop all our own wood in the winter time and all’ (p.119). The 16-year-old knows he is supposed to resign—he talks about being told that ‘Life being a game…you should play it according to the rules’ (p.7), to feeling ‘so damn lonesome’ (pp.42 & 134) and ‘depressed’ (multiple references) he even felt like ‘committing suicide’ (p.94). As a result of all this disenchantment with the world he keeps ‘failing’ (p.9) all his subjects at school and as a result had to leave four schools for ‘making absolutely no effort at all’ (p.167). He says about his behaviour, ‘I swear to God I’m a madman’ (p.121) and ‘I know. I’m very hard to talk to’ (p.168). Finally he finds some empathy from an adult who says ‘This fall I think you’re riding for—it’s a special kind of fall, a horrible kind…[where you] just keep falling and falling [utter depression]’ (p.169). The adult then spoke of men who ‘at some time or other in their lives, were looking for something their own environment couldn’t supply them with…So they gave up looking [resigned]…[adding] you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior’ (pp.169-170). Summarising the horror of having to resign the 16-year-old says: ‘I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be’ (p.156). Yes, finally the reconciling understanding of the human condition has arrived that provides ‘the catcher in the rye’, the means to ‘catch everybody’ before ‘they start to go over the cliff’ that Holden Caulfield so yearned for! The Catcher in the Rye has rightly been considered a masterpiece, and with understanding of the process of Resignation and how adults have lived in denial of it, it becomes even more impressive, if that were possible! (The Scottish author, J.M. Barrie’s 1902 story of Peter Pan who has a never-ending childhood is also a story of the dream of not having to become a tragic, resigned, effectively dead adult. Yes, it is going to be a world full of Peter Pan’s now, a world of unresigned, soul-alive adults.)

(As I mentioned, a more complete description of Resignation is given in the ‘Resignation’ chapter of my book A Species In Denial, which can be accessed at <www.humancondition.com/asid-resignation>.)

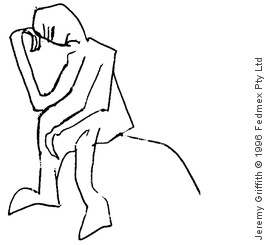

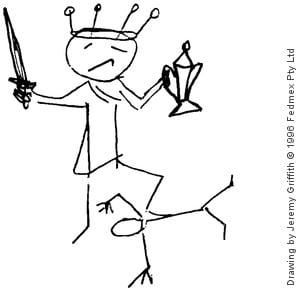

The following drawings summarise the agonising journey through Resignation.

A young person (or relatively innocent race) trying to understand the upset,

immensely dishonest and deluded, human-condition-afflicted world around them.

An adolescent grappling with the suicidally depressing

agony of the human condition within themselves.

The moment of Resignation when the adolescent gave up trying to understand why the world

and they were not ideally behaved and committed their mind to blocking out the unbearably

confronting truth of the existence of our species’ original instinctive self or soul’s ideal-behaviour-

demanding moral world, and of the existence of Integrative Meaning, and instead took up a

life of seeking as much relieving power, fame, fortune and glory as they could find.

Having resigned, the adolescent became another deluded, artificial, superficial,

immensely egocentric and selfish, power-fame-fortune-and-glory seeking resigned adult.

The end-play, terminal alienation, ‘abomination that causes desolation’,

doubly-deluded, human-journey-subverting, pseudo-idealistic resigned adult.