Freedom Expanded: Book 2—Questions & Answers

Section 1:4 What exactly is the human condition?

QUESTION: You spoke of humans being horrifically oppressed by the agony of the human condition and that being free of that condition is what TRANSFORMS us, but I’m not sure what, or at least I’m not relating to what, the human condition actually is.

ANSWER: It’s true—few people even know what the term ‘human condition’ actually means, or even that it exists, let alone that it is the underlying, core, real problem in human life. But, as mentioned, there is a very good reason for this: thinking about the issue of the human condition has been far too depressing. In fact, the human condition has been such a fearfully depressing subject we humans spend most of our time just making sure we avoid any encounter with the damn thing. Indeed, we only ever mentioned the term ‘human condition’ when we were being really profound, and even then it sent shivers down our spine.

So yes, what exactly is the human condition? As I summarised earlier, the human condition arises from the existence of so-called ‘good and evil’ in our make-up. We humans are capable of shocking acts of inhumanity like rape, murder and torture and our agonising predicament or ‘condition’ has been that we have never been able to explain and thus understand why. Even in our everyday behaviour, why are we competitive, aggressive and selfish when clearly the ideals of life are to be the complete opposite, namely cooperative, loving and selfless?

This predicament or ‘condition’ of not being able to understand ourselves meant that the more we tried to understand ourselves—that is, the more we tried to think about this obvious and most important question about human behaviour of why is it so imperfect—the more depressed our thoughts became. Clearly, to avoid becoming suicidally depressed, we learnt—and learnt very early on in our lives—not to allow our minds to go on that thought journey. We learnt to totally avoid the whole depressing subject of the human condition.

Certainly—and quite understandably given how guilty we have felt about our seemingly imperfect behaviour—we invented excuses for being competitive, aggressive and selfish. As I mentioned, the main excuse we have used is to say we have savage animal instincts that make us fight and compete for food, shelter, territory and a mate. But, in our heart of hearts, we knew this was only the excuse we had to use until we found the real reason for our divisive behaviour. As I said, it conveniently overlooks the fact that our human behaviour involves our unique fully conscious thinking mind. Descriptions of our behaviour, like egocentric, arrogant, deluded, artificial, hateful, mean, immoral, alienated, etc, all imply a psychological dimension to our behaviour. The psychological problem in our species’ thinking minds that we have suffered from is the dilemma of our human condition, the issue of our species’ good-and-evil-afflicted, less-than-ideal, seemingly imperfect, even ‘fallen’ or corrupted state. We humans suffer from a consciousness-derived, psychological human condition, not an instinct-controlled animal condition; it is unique to us.

The savage-animal-instincts-in-us excuse also overlooks the fact that we humans have altruistic, cooperative, loving moral instincts—what we recognise as our ‘conscience’—and I should say, and I explain this in Parts 4:12 and 8:4 of Freedom Expanded: Book 1, these moral instincts in us are not derived from reciprocity, from situations where you only do something for others in return for a benefit from them, as some biologists would have us believe, and nor is it a product of the cooperation that was allegedly forged through warring between groups of humans, as E.O. Wilson now asserts. No—we have an unconditionally selfless, fully altruistic, truly loving, genuinely moral conscience. Our original instinctive state was the opposite of being competitive, selfish and aggressive: it was cooperative, selfless and loving.

While we have understandably grimly held on to such excuses as blaming our ‘dark side’ on our supposed savage animal instincts, our moral conscience knows full well that we humans have loving and kind—not aggressive and mean—instincts. When we are young and haven’t yet embraced such dishonest excuses it is very obvious to us that there is something extremely wrong with the way humans are behaving, which we then try to understand. At about 11 or 12 years of age we all, in our naivety, did naturally start thinking about the incredible imperfection of human life—about why there is so much suffering in the world when, seemingly, there could and should be so much happiness, togetherness and love, and about all the hatred, cruelty, indifference and greed that is causing all that suffering. By about 14 or 15 our thinking about the human condition deepened to the point where we realised that those imperfections, like indifference towards others, anger, even hatred, selfishness and greed, also existed within ourselves. It was at this point of discovering that the human condition existed not only in the world without but also within that trying to understand the human condition without an honest explanation for it became so unbearably—in fact, suicidally—depressing that we realised we had no choice but to resign ourselves to never ever again revisiting the subject of the human condition.

And throughout this process adults couldn’t help adolescents because they, of course, had already resigned to living in denial of the issue of the human condition. In the following passage from his book The Moral Intelligence of Children, the Pulitzer Prize-winning child psychiatrist Robert Coles provides an exception to this ‘rule’ by giving a very rare account by an adult of a teenager in the midst of Resignation: ‘I tell of the loneliness many young people feel…It’s a loneliness that has to do with a self-imposed judgment of sorts…I remember…a young man of fifteen who engaged in light banter, only to shut down, shake his head, refuse to talk at all when his own life and troubles became the subject at hand. He had stopped going to school…he sat in his room for hours listening to rock music, the door closed…I asked him about his head-shaking behavior: I wondered whom he was thereby addressing. He replied: “No one.” I hesitated, gulped a bit as I took a chance: “Not yourself?” He looked right at me now in a sustained stare, for the first time. “Why do you say that?” [he asked]…I decided not to answer the question in the manner that I was trained…Instead, with some unease…I heard myself saying this: “I’ve been there; I remember being there—remember when I felt I couldn’t say a word to anyone”…The young man kept staring at me, didn’t speak…When he took out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes, I realized they had begun to fill’ (1996, pp.143-144 of 218). The boy was in tears because Coles had reached him with some recognition and acknowledgement of what he was wrestling with; Coles had shown some honesty about what the boy could see and was struggling with, namely the horror of the utter hypocrisy of human behaviour—which all those who had already resigned to living in denial of the human condition had determinedly committed their minds to not recognising.

The words Coles used in his admission that he too had once grappled with the issue of the human condition, of ‘I’ve been there’, are exactly those used by one of Australia’s greatest poets, Henry Lawson, in his exceptionally honest poem about the human condition, about the unbearable depression that results from trying to confront the question of why human behaviour is so at odds with the cooperative, loving—or to use religious terms, ‘Godly’—ideals of life. In his 1897 poem The Voice from Over Yonder Lawson wrote: ‘“Say it! think it, if you dare! Have you ever thought or wondered, why the Man and God were sundered [torn apart]? Do you think the Maker blundered?” [Do you think humans are evil and a mistake?] And the voice in mocking accents, answered only: “I’ve been there.”’ The unsaid words in the final phrase, ‘I’ve been there’, are ‘and I’m not going there again!’—with the ‘there’ and the ‘over yonder’ of the title being the state of deepest, darkest depression.

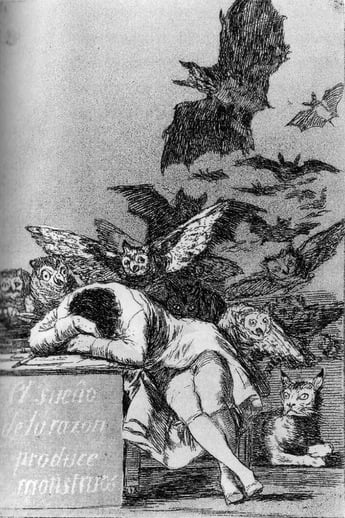

Interestingly, in his best-selling 2003 book about the great Spanish artist Francisco Goya, titled Goya, the renowned Australian art critic Robert Hughes, described how he ‘had been thinking about Goya…[since] I was a high school student in Australia…[with] the first work of art I ever bought…[being Goya’s most famous etching] The sleep of reason brings forth monsters…[which shows] the intellectual beset with doubts and night terrors, slumped on his desk with owls gyring around his poor perplexed head’. Hughes then commented that ‘glimpsing The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was a fluke’ (p.3, 4). A little further on, Hughes wrote that ‘At fifteen, to find this voice [of Goya’s]—so finely wrought [in The sleep of reason brings forth monsters] and yet so raw, public and yet strangely private—speaking to me with such insistence and urgency…was no small thing. It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it’ (p.5). Again, the process of Resignation is such a horrific experience that adolescents determined never to revisit it, or even recall it, nevertheless, Hughes’ attraction to The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was not the ‘fluke’ he thought it was. The person slumped at the table with owls and bats gyrating around his head perfectly depicts the bottomless depression that occurs in humans just prior to resigning to a life of denial of the issue of the human condition, and someone in that situation would have recognised that meaning instantly, almost wilfully drawing such a perfect representation of their state out of the world around them. Even the title is accurate: ‘The sleep of reason’—namely reasoning at a very deep level—does ‘bring forth monsters’. While Hughes hasn’t recognised that what he was negotiating ‘At fifteen’ was Resignation, he has accurately recalled how strong his recognition was of what was being portrayed in the etching: ‘It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it.’ Note that Hughes’ words ‘I have been through it’ are almost identical to Coles and Lawson’s words ‘I’ve been there.’

So there are some very revealing admissions of just how fearfully depressing the issue of the human condition has been.

Of course, living in denial of the issue of the human condition meant the adult world couldn’t acknowledge the process of Resignation—you can’t very well maintain a denial if you admit you are practicing denial; you can’t effectively lie if you admit you are lying. And so, unable to acknowledge the process of Resignation, adults instead blamed the well known struggles of adolescence on the hormonal upheaval that accompanies puberty, the so-called ‘puberty blues’—even terming glandular fever, a debilitating illness which often occurs in mid-adolescence, a puberty-related ‘kissing disease’. These terms, ‘puberty blues’ and ‘kissing disease’, are dishonest, denial-complying, evasive excuses because it wasn’t the onset of puberty that was causing the depressing ‘blues’ or glandular fever, but the trauma of Resignation, of having to accept the death of your true self or soul. For glandular fever to occur a person’s immune system must be extremely rundown, and yet during puberty the body is physically at its peak in terms of growth and vitality—so for an adolescent to succumb to the illness they must be under extraordinary psychological pressure, experiencing stresses much greater than those that could possibly be associated with the physical adjustments to puberty, an adjustment that, after all, has been going on since animals first became sexual. The depression and glandular fever experienced by young adolescents are a direct result of the trauma of having to resign to never again revisiting the subject of the human condition. If you watch Anthony Landahl’s Affirmation of the TRANSFORMED STATE in Section 3:8 of this presentation you can feel the absolute agony of someone recalling the time they went through Resignation and suffered from glandular fever. Much, much more is said about Resignation in Part 3:8 of Freedom Expanded: Book 1, for it is the most important and yet almost completely unacknowledged psychological event in human life.

One of the rare few individuals who did manage to defy the practice of denial of the human condition was the great psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who gave this deadly accurate description of it: ‘When it [our shadow] appears…it is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience for him to gaze into the face of absolute evil’ (Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, 1959, tr. R.F.C. Hull; in The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 9/2, p.10). Yes, it was ‘a rare and shattering experience’ for resigned adults to allow their minds to confront the question of why their behaviour is so diabolically at odds with what ideal behaviour should be—despite it being the stark staring obvious question that had to be addressed and explained if we humans were to ever understand ourselves.

So although it is the core issue in our lives—and the issue that had to be solved for there to be a future for the human race—adults do, as the question illustrates, find it very difficult even recognising what the subject of the human condition is, and the reason for that bewilderment is not because it is an unfamiliar subject, as we tend to think, but because we have been living in very deep, determined psychological denial of the whole depressing subject—and have been for a very long time; in fact, as is emphasised throughout this presentation and fully explained in Freedom Expanded: Book 1, this practice of denial has been going on since humans’ conscious, self-managing mind fully developed and the human condition became full blown some two million years ago!

In 2010, the American heavy metal band With Life In Mind produced a song they actually titled The Human Condition, which contains this rare and amazingly honest description of the human condition: ‘We’re staring through the eyes of a bitter soul. Constantly surrounded by this empty feeling…Never good enough for those ideals that seem to mean the most…Driven into madness, I see no end in sight, and inadequacy seems like the only means to pass through this life. And I sit and ask myself when will it end? The art of contention is an uphill battle I’m not ready to fight.’ Yes, unless we resigned ourselves to giving up trying to ‘conten[d]’ with it, confront it, stop trying to live ‘with’ the issue of ‘life in mind’, we would be ‘driven into madness’ with ‘no end in sight’ to the unbearably depressing ‘empty feeling’ caused by the terrible ‘inadequacy’ of our seemingly horrifically imperfect ‘human condition’! Denial of the human condition has been the only way we have been able to cope with the human condition while we couldn’t explain it!

With Life In Mind’s Grievances album, which includes the song The Human Condition, also contains many other tracks that feature deadly accurate lyrics about the human condition, including: ‘It scares me to death to think of what I have become…This self loathing can only get me so far’; ‘Our innocence is lost’; ‘I can’t express all the hate that’s led me here and all the filth that swallows us whole…A world shrouded in darkness…Fear is driven into our minds everywhere we look’; ‘We’ve been lying to ourselves for so long, we truly forgot what it means to be alive…How could we ever recover? Lost in oblivion…Shackled in chains, bound and held down…We could never face our own reflections in the mirror’; ‘We’ve all been asleep since the beginning of time. Why are we so scared to use our minds?’; ‘You’re the king of a world you built for yourself, but nothing more than a fraud in reality’; ‘How do we save ourselves from this misery…So desperate for the answers…We’re straining on the last bit of hope we have left. No one hears our cries. And no one sees us screaming’; ‘Our fight is the struggle of man…This is the end.’ Yes, to avoid ‘the struggle of man’, and ‘the end’ of suicidal depression from trying to confront the issue of the human condition while we couldn’t explain it, there most definitely has been no alternative but to live in complete denial of the issue—and this does make it very difficult ‘relating to what the human condition actually is’, as the questioner said.

Incidentally, I should warn that this great, embedded ‘fear’ of the human condition in the ‘minds’ of adults is also the reason why it is very hard to take in discussion about the human condition—any reference to it creates a ‘deaf effect’ where the fear won’t allow our minds to absorb what is being said and so we are left thinking that what has been said or written doesn’t make any sense or is unclear. As someone once admitted to me, ‘When I first read your books all I saw were a lot of black marks on white paper.’ Talking about the human condition can be so confronting that all we initially hear is ‘white noise’—in effect, our mind is saying, ‘I tried to look at the human condition once before—‘I’ve been there’, as Coles and Lawson said—and I’m not about to make that mistake again.’ So while the issue of the human condition has at last been rendered safe to confront, initially our old fears dominate, which is why these all-precious understandings of the human condition will take a little time to become widely appreciated.

What is needed to overcome this ‘deaf effect’ is a preparedness to re-read and/or re-listen to what is being written or said about the human condition, as you will be surprised at how you can begin to ‘hear’ it, take it in. In 2011, a writer, identified only as ‘Fitzy’, published an online article about my work, in which he admitted that he too initially suffered from the ‘deaf effect’ but overcame it with a second reading: ‘The core concepts keep slipping from my mental grasp, at the time I put it down to bad writing, however a second reading revealed something the Author had indicated from the outset—your mind doesn’t want to understand the content. The second read was quick and painless’ (Humanitus Interruptus – Great Minds of Today, accessed 24 Oct. 2011, see <www.wtmsources.com/106>). (Much more is said about the problem of the deaf effect in Part 3:13 of Freedom Expanded: Book 1. And the WTM now offers a Deaf Effect Course at <www.humancondition.com/freedom-essays/the-wtm-deaf-effect-course>).

To summarise what I said earlier, our human predicament or ‘condition’ has been that because we humans have never been able to explain and thus understand our less-than-ideal behaviour we carry a deep, now almost subconscious, insecurity and sense of guilt about our value and worth as humans. Are we good or are we bad?

So that is what the human condition is—the agony of not being able to explain and thus understand our extraordinarily contradictory human behaviour. Until now. And, as emphasised, what is so wonderful—in fact, SO wonderful it will TRANSFORM your life and the lives of all humans—is that the explanation of the human condition that has finally been found is compassionate. It explains that there has been a good reason for why we humans have not been ideally behaved. It is an explanation that dignifies and redeems us. It provides ‘the answers’ that ‘save ourselves from this misery’ of ‘the human condition’ that we have been ‘so desperate for’. It is the explanation that reconciles the opposites of good and evil in our natures and in doing so makes us whole again—thus TRANSFORMING the whole human race, an outcome that, as the lyrics to Beethoven’s music proclaimed, will make us so ‘joyful’ it will be as if we are ‘drunk with fire’.

______________________

I need to add a warning to this description of the human condition that I gave in 2011. It is now 2012 and the famous American biologist Edward (E.) O. Wilson has recently published a new book titled The Social Conquest of Earth in which he presents an explanation of the human condition that doesn’t equate at all with the fearful description of the human condition that I have just given.

As I fully explain in Part 4:12I of Freedom Expanded: Book 1, this new ‘Theory of Eusociality’ (as E.O. Wilson has termed his supposed explanation of the human condition) doesn’t truthfully explain the human condition at all, rather it attempts to dismiss it as nothing more than a conflict between supposed selfish and selfless instincts within humans. It is not a profound, truthful treatment of the psychological dilemma within us humans that is the real human condition that we suffer from, but rather a completely fake, superficial trivialisation of the subject.

What Wilson has done is put forward a supposed explanation of the human condition that nullifies it, that makes it appear benign, nothing profoundly distressing at all, when, as the descriptions I have just given of adolescents going through Resignation make very, very clear, the human condition is, in reality, a profoundly deep, extremely dark and fearful—indeed terrifying—psychological issue.

As is described in Part 4:12 of Freedom Expanded: Book 1, in devising such theories as Social Darwinism, Sociobiology, Evolutionary Psychology, Multilevel Selection and now Eusociality, mechanistic/reductionist science has become masterful at finding new ways to avoid the true nature of the human condition. But unlike all these escapist, superficial, completely fake, dishonest interpretations of human nature, especially Wilson’s theory of Eusociality, what is going to be presented here is the fully accountable and thus true biological explanation of the agonising, core issue of our human condition—the explanation that finally explains the real, psychological dilemma that adolescents going through Resignation know all too well, and which the world so desperately requires if it is to avoid the effects of terminal alienation.