‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 8 The Greatest, Most Heroic Story Ever Told

Chapter 8:2 The stages of humanity’s maturation from ignorance to enlightenment

We begin this most amazing story of humanity’s journey from ignorance to enlightenment by meeting with our ancestors through the wonderfully fortuitous fossilised remains we have of them.

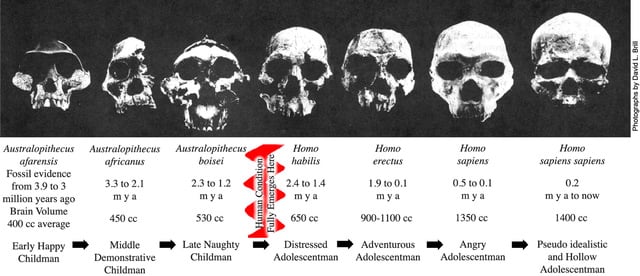

The above photo sequence of fossil hominin (human ancestor) skulls, dating back to the beginning of the australopithecines, appeared in the November 1985 edition of National Geographic magazine. Of course, as explained in chapter 2, mechanistic science hasn’t recognised—indeed, has determinedly avoided—the psychological nature of our human condition, so the psychological descriptions for each of the stages of our development given above of ‘Early Happy Childman’, then ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’, and so on, are my additions. Further, anthropologists no longer consider the robustly built Australopithecus boisei to be one of our direct ancestors but part of a now extinct branch line of development. However, as I will explain in pars 733-737, I disagree that there was any branching in the progression from the ape state to humans today, because for branching to occur there has to be deflecting influences—such as when Darwin’s finches gradually became adapted to different food niches on the Galápagos Islands—and in our case there was only one major development going on and that was the psychological one. In a situation where there is only one all-dominant influence causing change there is no opportunity for divergence to develop, and from our species’ infancy we have been under the all-dominant influence of what was occurring in our brains, namely the development of consciousness and its psychological consequences. Any other influence was so secondary as to be ineffectual in causing our path to branch. In the case of Homo habilis fossils shown here as predating A. boisei, I strongly suspect that future fossil finds will push back the date of A. boisei and confirm the order depicted above, with A. boisei emerging from Australopithecus africanus, and giving rise to H. habilis. The reason for the overlap in the stages is explained in par. 735. Also, while anthropologists have since discovered more varieties of Australopithecus and Homo than those depicted here, these remain representative of the main varieties. There is also argument within the scientific community as to when to change the name as one variety develops into the next; for example, the varieties of Homo designated here as Homo sapiens and Homo sapiens sapiens may be referred to in other texts as the more ‘archaic Homo sapiens’ and as the more ‘anatomically modern Homo sapiens’ respectively. So the names used here are simply the traditional ones. Finally, the fossils that have been found to belong to our forebears who existed prior to the australopithecines are not included in this picture, but they too will be accounted for shortly.

In examining this sequence it is apparent that a sudden increase in the size of the brain case, and by inference the brain’s volume, occurred around 2 million years ago. A larger brain case was needed to house a larger ‘association cortex’. As explained in pars 633-639, the ability to ‘associate’ information is what made it possible to reason how experiences are related, learn to understand and become conscious of, or aware of, or intelligent about, the relationship between events that occur through time. It follows that the development of a larger association cortex meant that a greatly increased need for understanding had emerged, which we are now able to explain would have resulted from the emergence of the dilemma of the human condition, where only self-understanding could bring an end to all the psychological upset that condition has produced and which has been so crippling of our species’ development and that of our own lives. The inference we can take from this evidence is that the human condition became a full-blown problem some 2 million years ago with the emergence of Homo.

The descriptions I have provided below the picture of the various fossil hominid skulls document the stages humanity progressed through as this liberated consciousness developed. The names ascribed to each stage indicate parallels with our own human life-stages, because the stages that we, as conscious individuals, progress through are the same stages our human ancestors progressed through—‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’: our individual consciousness necessarily charts the same course that our species’ consciousness has taken as a whole. Eugène Marais recognised this when he wrote that ‘The phyletic history of the primate soul can clearly be traced in the mental evolution of the human child’ (The Soul of the Ape, written between 1916-1936 and published posthumously in 1969, p.78 of 170). Wherever consciousness emerges it will first become self-aware (the ‘Infancy’ stage of the development of a conscious mind), then, inevitably, it will start to experiment with its power to effectively understand and thus manage change (the ‘Childhood’ stage), following which it will seek to understand the meaning behind all change (‘Adolescence’), and from there it will obviously try to comply with that meaning (‘Adulthood’).

In the case, however, of consciousness developing within us individually now and in our ancestors, that journey was significantly disrupted at adolescence by our search for the understanding of why we—individually and as a species—were not behaving in accordance with the integrative, cooperative meaning of existence; adolescence being the stage in the development of consciousness where the search for identity takes place, where the search for understanding of the meaning behind change, and the conscious organism’s relationship to that meaning, occurs. In the case of our individual lives now, and in this stage in our species’ journey, the particular identity we needed to find understanding of was why we were behaving divisively when the meaning of existence is to behave cooperatively and lovingly. Until we could answer that question, our development, both individually and collectively, was stalled (or what psychologists refer to as ‘arrested’) in an insecure adolescent state, unsure of our identity, particularly the reason why we haven’t been ideally behaved—and preoccupied trying to validate our existence, prove that we are good and not bad, find some relief from the insecurity of the human condition. So, to mature from insecure adolescence to secure adulthood depended on finding understanding of our divisive human condition.

To go over this important point again, without understanding of the human condition, humans haven’t been able to properly enter adulthood. When stages of maturation aren’t properly completed it doesn’t mean subsequent growth stages don’t take place, they do, but if a previous stage isn’t properly fulfilled those subsequent stages are greatly compromised by the incomplete preceding stages. People do grow up, but in a state of arrested development. Without the explanation of the human condition, humans have been insecure, not properly developed—in fact, completely preoccupied justifying themselves and finding ways to escape feeling unworthy. As the actress Mae West once famously said about men, ‘If you want to understand men just remember that they are still little boys searching for approval.’ So it is only with understanding of the human condition now found that humans will be able to properly complete their adolescence and grow into secure adults, and the human race as a whole will be in a position to mature from insecure adolescence to secure adulthood. This is why descriptions such as ‘The Angry Adulthood Stage of Humanity’s Adolescence’ appear in the following stages to describe our species’ progression, for while we became adults in a physical sense, without the explanation of the human condition we were still psychologically stranded in adolescence.

In summary, infancy is ‘I am’, childhood is ‘I can’, adolescence is ‘but who am I?’, while adulthood is ‘I know who I am.’

To apply these stages involved in the development of consciousness to the journey through which our species progressed, the term ‘Infantman’ pertains to the ape ancestor who first developed the nurturing training in selflessness that produced the fully cooperative state and, in doing so, liberated consciousness. As described in chapter 5:5, fossils from this period, which dates from 12 to 4 million years ago, are rare; however, scientists believe that our ape ancestors from this period include Sahelanthropus tchadensis (who lived some 7 million years ago and is thought to be the first representative of the human line after we diverged from humans’ and chimpanzees’ last common ancestor); Orrorin tugenensis (who lived some 6 million years ago); and the two varieties of Ardipithecus: kadabba (who lived some 5.6 million years ago), and ramidus (who lived some 4.4 million years ago). The various stages of ‘Childman’, who, it follows, developed from ‘Infantman’, were, as just summarised under the picture of the skulls above, the australopithecines who began to experiment with the power of conscious free will: ‘Early Happy Childman’ (Australopithecus afarensis), who developed into ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’ (Australopithecus africanus), who then developed into ‘Late Naughty Childman’ (Australopithecus boisei). Again, at each stage greater experimentation in conscious self-management was taking place—from demonstrating the power of free will in mid-childhood, to beginning to challenge the instincts for the right to manage events in late childhood.

As has now been explained, this challenging of our instincts led to criticism from those instincts, which in turn upset our conscious mind. In late childhood this emerging upset expressed itself in the physical flailing out at the ‘unjust world’—the ‘naughty nines’, as parents and teachers describe this stage. What occurs to bring an end to childhood at about the age of 12, and what would have occurred at the end of the childhood stage in our ancestors around 2 million years ago, is the realisation that physically protesting and flailing out doesn’t achieve anything and that what we need to do instead is calm down, take stock of our situation, and try to understand what is causing us to be so upset; try to find the explanation for why we are being criticised. This significant change from being a frustrated, protesting, boisterous extrovert to a sobered, deeply thoughtful introvert signals the beginning of adolescence. Although unaware of the underlying reason, anthropologists have, nevertheless, recognised that a significant change did take place around 2 million years ago because it was at this juncture that they changed the name of the genus from Australopithecus to Homo; ‘Childman’, the australopithecines, became ‘Adolescentman’, Homo.

As stated, adolescence is the stage when the search for identity takes place, and the identity that ‘Adolescentman’, Homo, particularly sought to understand was their lack of ideality—the reason why they were not ideally behaved. And once begun, this march of upset could only be brought to an end by finding sufficient knowledge to explain why the instincts’ ‘criticism’ was undeserved. As such, there was an ever increasing need for mental cleverness to explain ourselves—specifically to find the liberating understanding of the human condition—hence the rapid increase in brain volume from 2.4 million years ago onwards.

As with our species’ progression through the various stages of its childhood, when our species entered its adolescence we necessarily went through a similar progression of stages, starting with the early sobered-by-the-emerging-problem-of-the-human-condition Adolescentman stage (early Homo habilis), followed by the distressed-by-the-human-condition Adolescentman stage (late Homo habilis), through to the adventurous Adolescentman stage (Homo erectus, who first left Africa), the embattled angry Adolescentman stage (Homo sapiens), and the pseudo idealistic and hollow Adolescentman stage that we currently occupy (Homo sapiens sapiens). But with the finding of understanding of why we have been divisively behaved now found, humans individually, and humanity collectively, can finally mature from this insecure adolescence to a secure adulthood: ‘Adolescentman’ can become transformed ‘Adultman’. (Note, ‘man’ is an abbreviation for ‘human’ or ‘humanity’, however, the use of ‘man’ also denotes a recognition that while humanity’s infancy and childhood was matriarchal or female-role-led because that was when nurturing of infants was all-important, with the emergence of the egocentric, male-role-led need to defy the instincts, search for knowledge and prove humans are good and not bad, humanity’s adolescence became patriarchal—a transition that will be more fully explained shortly (in pars 769-770). Since humanity’s adulthood will be neither female or male led—because our species’ maturation is complete—‘Adultman’ should more properly be described as ‘Adulthuman’. By the same logic, since humanity’s childhood was female role-led, the description for that stage should be ‘Childwoman’ rather than ‘Childman’, but to avoid unnecessarily complicating the matter we will leave all as ‘man’ for now.)

We will now examine these various stages that a conscious mind has to progress through from infancy to childhood to adolescence and adulthood, looking at the individual living in the world today, and how these stages manifested within humanity’s journey overall.