‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 8 The Greatest, Most Heroic Story Ever Told

Chapter 8:6 Middle Demonstrative Childman

The species: Australopithecus africanus — 3.3 to 2.1 million years ago

The individual now: 7 and 8 years old

It is during the ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’ stage that the intellect starts demonstrating the power of free will and experiences its first encounter with the frustrations of a conflict with the instincts, which is the human condition.

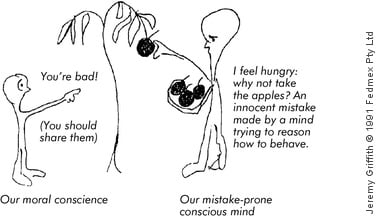

By mid-childhood the conscious mind is sufficiently able to make sufficient sense of experience to successfully manage and thus plan activities for not just minutes ahead, but for hours and even days—a development that empowers the individual to be both outwardly marvelling at, and demonstrative of, its intellectual power. It is at this stage of active self-management that the results of some experiments in self-adjustment begin to get the child into trouble. If we consider the behaviour of children today who have reached this stage, we can appreciate the kind of trouble that entails. Imagine a young boy sitting at a table with a birthday cake on it. Being new to this business of reasoning, he thinks, innocently enough, ‘Well, why shouldn’t I take all the cake for myself’, before duly doing so. While many mothers actually witness these grand mistakes of pure selfishness that young children make when they first attempt to manage their lives from a basis of understanding, they still have to be reasonably lucky to do so because, once done, the child generally doesn’t make such a completely naive mistake again due to the criticism that experiment in self-management attracts from the child’s instinctive moral conscience and from his conscious mind’s awareness of the, in truth, very obvious integrative, selfless theme of existence—as well as from others present. But despite the nasty shock from all the criticism and his desire to not make such a mistake again, the boy, while unable to explain his actions, does feel that what he has done is not something bad, not something deserving of such criticism. In fact, by this stage in the child’s mental development, he has become quite proud of the effort he’s taken during his early happy innocent childhood stage to self-manage his life, successfully carrying out all kinds of tentative experiments in self-adjustment—drawing attention to his achievements with excited declarations like ‘Look at me, Daddy, I can jump puddles’, and so on. So the child is only just discovering that this business of self-adjusting is not all fun and that ‘playing’ with the power of free will leads to some serious issues. Indeed, the frustrated feeling of being unjustly criticised for some of his experiments gives rise to the precursors of the defensive, retaliatory reactions of anger, egocentricity and alienation; some angry, aggressive nastiness creeps into the child’s behaviour. (As was explained in chapter 3:5, this retaliatory behaviour brings about the ‘double and triple whammy’ of condemnation that humans experienced when we searched for knowledge.) Furthermore, in this situation of feeling unfairly criticised, it follows that any positive feedback or reinforcement begins to become highly sought-after, which is the beginning of egocentricity—the conscious thinking self or ego starts to become preoccupied trying to defend its worth, assert that it is good and not bad. At this point, the intellect also begins experimenting in ways to deny or deflect the unwarranted criticism, which, in this initial, unskilled-in-the-art-of-denial stage, takes the form of blatant lying: ‘But, Mum, Billy told me to do it’, or ‘But, Mum, the cake accidentally fell in my lap.’ These apparent misrepresentations weren’t actually lies, rather they were inadequate attempts at explanation. Lacking the real excuse or explanation, it was at least an excuse, a contrived defence for the child’s mistake. The child was evading the false implication that his behaviour was bad, in the sense that a ‘lie’ that said he wasn’t bad was less of a ‘lie’ than a partial truth that said he was. Basically, the child has started to feel the first aggravations from the horror of the injustice of the human condition—and we can expect that exactly the same kind of mistakes in thinking and resulting frustrations with the ensuing criticism would have also occurred in the lives of our ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’ ancestors, namely Australopithecus africanus. Experiments in thinking, such as ‘There is some fruit; why shouldn’t I take it all for myself?’, would have occurred, which would have resulted in criticism from their moral instincts and conscious mind’s awareness of the integrative, selfless theme of existence—criticism that would have led to the beginnings of the psychologically upset behaviours of anger, egocentricity and alienation in Au. africanus.

While children today have to—just as our Au. africanus ancestors would have had to—negotiate this middle demonstrative stage where at times they behave in a way that is ‘disobedient’ of their moral instincts and ‘defiant’ of the integrative theme of existence, their conscious mind still doesn’t know why it has been disobedient and defiant; it isn’t able to understand and explain that it has become a conscious being. Also, now that they are capable of thought they can’t stop thinking, which means mistakes in self-management are going to continue to occur, as will the criticism those mistakes attract, and, it follows, the upset with that criticism. Yes, from demonstrating the power of free will, the child has started to feel the first aggravations from the horror of the injustice of the human condition. Of course, for our ‘Middle Demonstrative Childman’, Au. africanus ancestors, love would still have very much been the dominant influence in their lives overall, which means any distress from upset would have been quickly healed with love. Furthermore, the defensive expressions of anger, egocentricity and denial would have been restricted to feelings and actions rather than expressed in words; in fact, there would not have been a strong call for language until the adolescent state emerged some 2 million years ago when the battle of the human condition developed and, with it, alienation, because it was only when we became variously alienated in self and thus variously alienated from each other that a strong need to try to justify and explain ourselves to one another arose. The anthropologist Richard Leakey’s study of brain cases in fossil skulls for the imprint of Broca’s area, the word-organising centre of the brain, evidences this development: ‘Homo had a greater need than the australopithecines for a rudimentary language’ (Origins, 1977, p.205 of 264). Prior to the emergence of alienation we were all instinctively aware of and in sync with each other; apart from contact, orientating and warning calls, and expressions of excitement and joy, there was no need to develop a sophisticated, complex language. As Plato described life during ‘our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come’, we lived a ‘blessed and spontaneous life…[where] neither was there any violence…or quarrel’ and ‘there were no forms of government’; it was a ‘simple and calm and happy’ life (see ch. 2:6).

While discussing the effects of alienation, it should be pointed out that infants would have stopped being quiet when mothers stopped being able to properly respond to their needs due to their alienated, soul-devastated condition. For instance, even the infants of relatively innocent, less alienated ‘races’ of humans today, such as the Yequana of Venezuela, the Australian Aborigine and the Bushmen of the Kalahari, rarely cry, as these remarkably similar quotes confirm: ‘[Yequana] babes in arms almost never cried’ (Jean Liedloff, ‘The Importance of the In-Arms Phase’, Mothering, Winter 1989; see <www.wtmsources.com/150>); and ‘!Kung [Bushmen]…infants hardly ever cry’ (Dr Harvey Karp, ‘Cultures without Colic: Breastfeeding & Other Baby Lessons from the !Kung San’; see <www.wtmsources.com/117>). Yes, motherese language developed as a way for alienated humans to try to pacify their distressed innocent infants.