‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 8 The Greatest, Most Heroic Story Ever Told

Chapter 8:11C Other adjustments to life under the duress of the human condition that developed during the reign of Adventurous Adolescentman

The overall point being made here is that since all forms of innocence unfairly criticised humans during our species’ insecure adolescence, all forms of innocence have been attacked by upset humans during this stage. As stated earlier, animals also fell victim to the human condition; and not only animals, but nature in the broader sense, because it too was a friend and ‘ally’ of our instinctive soul and, therefore, an ‘enemy’ of our apparently ‘bad’ conscious mind. Attacking nature, be it chopping down trees or setting fire to vegetation, brought a retaliatory sense of satisfaction to the upset within us. Even the wearing of dark glasses, ostensibly as sunshades, was often an effort to block or alienate ourselves from the natural world that was alienating us.

Indeed, if we take a moment to extrapolate this situation, we can see that eventually our upset was likely to increase so much, and our associated resentment of any criticism of it would become so great, that disputes with other humans were inevitably going to break out, at which point people would eventually start grievously attacking and even murdering each other, which would lead to, and, of course, has led to, outright, organised warfare—but, as will be explained during humanity’s 40-year-old equivalent stage, such extremely destructive behaviour didn’t emerge until the latter period of our 2 million years in adolescence.

Of course, the more upset we became, the more we needed ways to escape and relieve the trauma of our condition. And so to compensate for the extremely unhappy state of becoming corrupted, we began to seek out the material rewards of luxury and comfort, with this materialism becoming one of the main driving forces or motivations in life when upset became extreme. The accumulation of wealth and what it could offer us—the land, the staff, big houses, hordes of gold, glittering dresses, sparkling diamonds and shiny, pretentious cars—gave us the fanfare and glory we knew was due us, but which the world in its ignorance would not give us. From being bold, challenging and confrontationist, the heroic 21-year-old eventually became embattled, cynical and exhausted, greatly in need of escapism and relief, and thus an increasingly superficial, material and artificial person. We personally abandoned any idealistic hope of winning the battle to overthrow ignorance as to the fact of our true goodness and became realists, concerned only with finding material relief and bestowing glory upon ourselves.

As mentioned in par. 727, while innocent ‘Childmen’ were instinctively coordinated and connected, once upset, especially alienation, developed, language became a necessity. With alienation differing from one person to another, the need emerged to try to explain ourselves, to explain why we were behaving differently, in such a seemingly non-ideal manner. In fact, talking became the key vehicle for justifying ourselves, both in our minds and to others. But since we couldn’t speak directly about the human condition, or about other people’s particular states of alienation without overly confronting and condemning them, stories became a way of passing on knowledge, or what we call wisdom, about the subtleties of life under the duress of the human condition. Much later, with the development of the written word about 6,000 years ago, the fundamental quest for self-justification became greatly assisted because the wisdom acquired during each generation could be more accurately recorded, which meant that quite suddenly the accumulation of knowledge gained real impetus. But, it follows that throughout the upsetting journey through humanity’s adolescence our increasing need to somehow explain and justify ourselves with words, both oral and written, also led to the development and dissemination of all kinds of increasingly sophisticated excuses and lies for our behaviour. The industry of denial became one of the main features of our lives; indeed, the extreme denials that have taken place in science about our species’ innocent, upset-free, psychologically secure and happy past bear stark witness to just how sophisticated the art of denial has become.

At this point in our journey, other forms of self-expression, such as art and music, became particularly useful because, unlike language and stories, their often deep and important message wasn’t as clear and, therefore, as potentially confronting—as the writer Victor Hugo said, ‘Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to remain silent’ (William Shakespeare, 1864). Each person could derive as much meaning from the art or the music or even the dance and other cultural rituals as they could personally cope with. Of course, once humans became extremely alienated and had overly repressed their all-sensitive, beautiful world of their original instinctive self or soul because it was so condemning and confronting, then art, music and dance and other forms of cultural expression could also serve to reconnect them back to the soul’s true world. For example, Albert Camus recognised that ‘If the world were clear, art would not exist’ (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1942), and it is often said of great art that it ‘can make the invisible visible’; it can cut a window into our alienated, effectively dead state, make the world ‘clear’ and bring back into view some of the beauty that our soul has access to. After years of developing his skills, Vincent van Gogh was able to bring out so much beauty that resigned humans looking at his paintings find themselves seeing light and colour as it really exists for possibly the first time in their life: ‘And after Van Gogh? Artists changed their ways of seeing…not for the myths, or the high prices, but for the way he opened their eyes’ (Bulletin mag. 30 Nov. 1993). On the whole, culture essentially encompassed the various ways people passed on, from one generation to the next, the knowledge they had learnt about living under the duress of the human condition.

Although the oldest known cave paintings date back just 35,000 years, archaeologists working in Zambia announced in 2000 that they had found pigments and paint grinding equipment believed to be between 350,000 and 400,000 years old. At the time of the discovery it was reported that the find showed that ‘Stone Age man’s first forays into art were taking place at the same time as the development of more efficient hunting equipment, including tools that combined both wooden handles and stone implements…[and that it was evidence of] the development of new technology, art and rituals’ (BBC World News, 2 May 2000; see <www.wtmsources.com/162>). The British archaeologist Lawrence Barham, a member of the team in Zambia, described the find as the ‘earliest evidence of an aesthetic sense’ and that ‘It also implies the use of language’ (ibid). As just explained, language would have emerged with alienation because people would have then needed some way to account for their unnatural behaviour, and since we can expect alienation to have begun soon after the emergence of Homo we can assume that at least a rudimentary language would have been practised by H. habilis who emerged approximately 2.4 million years ago. With regard to other expressions of aesthetic sensitivity—a sensitivity we have had since we became instinctively immersed in love and in tune with all of nature during our love-indoctrinated past, but have not been able to reflect upon or express until our conscious mind and associated state of alienation reached a certain level of development—the oldest musical instruments found so far, phalange (bone) whistles, show that Neanderthals, the early variety of H. sapiens sapiens, were making music around 80,000 to 100,000 years ago, while a Neanderthal burial site at the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, estimated to be around 50,000 years old, contains traces of pollen grains, indicating that bouquets of flowers were buried with the corpses. The creative and aesthetic sense of our ancestors of nearly half a million years ago, as indicated by the pigments and paint grinding equipment, suggests that the creative and spiritual sensitivities demonstrated by the Neanderthals were in existence long before their time.

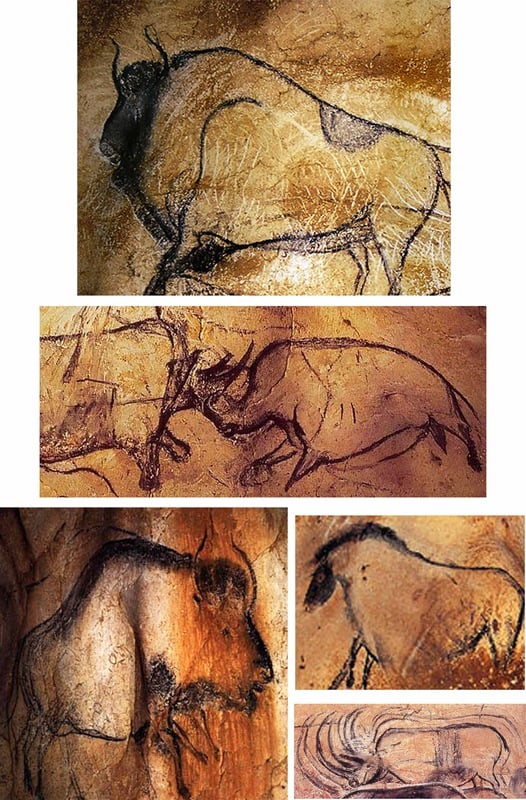

Extraordinarily empathetic renditions of animals in

the Chauvet Cave in southern France, c.30,000 years old

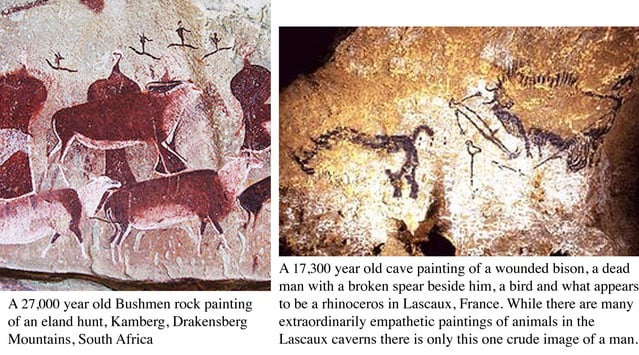

The extreme sensitivity that is particularly apparent in the rock paintings of the Bushmen of southern Africa and Australian Aborigines, and in the cave paintings of early humans in Europe, is especially revealing of how much innocence the human race has lost in relatively recent times. The Chauvet Cave in southern France, for example, contains a wealth of cave drawings that date from around 30,000 years ago (some of which are reproduced above) that have inspired such descriptions as ‘miraculous’, ‘overwhelming in density, humbling in sophistication, and awe-inspiring in sheer beauty’ (‘The Goddess Bites’; see <www.wtmsources.com/131>). The drawings are three dimensional, even animated; in short, the animals appear so real it is as if they are alive! You can almost feel what it is like to be those animals, the whole struggle of their lives is revealed.

I might mention that I learnt long ago that to draw the little pictures that are included throughout this book, I had to disconnect my conscious mind and just let my instinctive sensitivity express itself, and that if I didn’t do that I simply couldn’t draw at all. For example, the drawing of the three ‘Childmen’ happily embracing that I used in ch. 8:4 to illustrate humanity’s childhood stage was done so quickly I shocked myself because I could hardly believe that such an empathetic drawing could be produced from an almost instant scribble. At that moment I saw just how much sensitivity we humans once had, and how much alienation now exists within us 2-million-years’-embattled humans. Yes, the extraordinary empathy and accuracy of the paintings of animals in the rock and cave paintings shown above are similarly incredibly indicative of the amount of sensitivity we humans once had and have since lost; we truly are an embattled species now, so worn out, so brutalised. How extremely sensitive must early humans have been! Sir Laurens van der Post wasn’t exaggerating when he wrote about the relatively innocent Bushmen that ‘He and his needs were committed to the nature of Africa and the swing of its wide seasons as a fish to the sea. He and they all participated so deeply of one another’s being that the experience could almost be called mystical. For instance, he seemed to know what it actually felt like to be an elephant, a lion, an antelope, a steenbuck, a lizard, a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree’ (The Lost World of the Kalahari, 1958, p.21 of 253). Plato made a similar observation when, as mentioned in par. 174, he described our innocent ancestors as ‘having…the power of holding intercourse with brute creation [being able to relate to other animals]’.

When all the upset in humans heals the world is going to open up for us humans. Our long repressed all-loving and all-sensitive original instinctive self or soul is going to come back to the surface. We are going to be able to feel everything around us. We are going to have so much kindness and love and empathy for each other and our fellow creatures because we will, once again, be able to feel everything they are experiencing, including just how embattled the lives of animals are; they suffer enormously from the ‘animal condition’, from the unrelenting need to compete for food, shelter, space and a mate. While, through the nurturing, love-indoctrination process, our ape ancestors were able to break free from the tyranny of genes having to ensure their own reproduction, other animals remain stuck in a continuous cycle of competition. Unlike humans (and bonobos, who are in the midst of developing love-indoctrination), other animals can’t develop full unconditionally selfless cooperative instincts. And so above all else, it is this empathy with, this feeling for, the relatively short, brutish, forever-having-to-fight-for-your-chance-to-reproduce lives of animals that those who made these drawings have so sensitively expressed. To use Sir Laurens’ words, they ‘seemed to know what it actually felt like to be’ a bison, horse or rhinoceros. You can sense the whole internal struggle of the animals’ lives in these drawings. Their huge chests heave with their brutal and tough battle to survive and reproduce—they are struggling so much to endure their lot it is as if they have asthma! Yes, now that humans can get over the terrible agony of our ‘human condition’, we will again be able to empathise with the terrible agony of the ‘animal condition’. It’s not very nice to have to belt the living daylights out of others to ensure your genes reproduce, let alone other members of your own species—in fact, your cousins, uncles and even your own father! No, it is not at all easy being a non-human animal, and that is an extreme understatement, just as it has not been at all easy being an upset human, which is, of course, another extreme understatement!

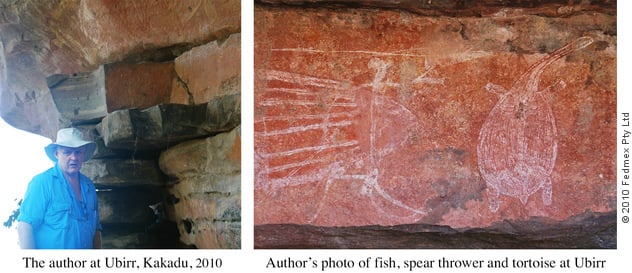

While the Paleolithic artists clearly weren’t as alienated as humans are today, they were still much, much more alienated than humans originally were. I think this is revealed by the fact that these cave artists almost completely avoided depicting humans. For instance, in the entire Chauvet Cave complex there is only one representation of a human, and even that is limited to a drawing of only the lower half of a woman’s torso. On the few occasions when these cave artists tried to depict humans they almost invariably ended up drawing stick figures. The human face, in particular, which you would think would be the most interesting and relevant of subjects for these artists to depict, seems to have been totally beyond their ability. It seems clear that the facial expressions of humans were by then so alienated, so devoid of the innocence that they must have once exhibited, that our instinctive self or soul couldn’t relate to it; it couldn’t, and perhaps didn’t want to, draw us. What did R.D. Laing say about our present alienated state: ‘between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’. The artist Francis Bacon revealed just how corrupted and alienated upset humans really are in his honest painting of the psychologically-contorted-smudged-human-condition-afflicted-face that was included after par. 124. Indeed, the weird, kidney-shaped blob for the human face that the Aboriginal artist drew in the rock painting shown below, from Ubirr in the Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia, is very Bacon-like! Revealingly, when I was looking at this painting at Ubirr, which is thought to be some 2,000 years old, I asked a guide, who was accompanying a tour group, whether she thought the reason the paintings of wildlife were so accurate while the paintings of the humans were so pathetic was because we are now too alienated for our soul to be able to empathise with us, the guide, and everyone else, reacted with a real shudder and audible choking noise. What I had said was just too close to the truth.

It is truly an insight into how sensitive and loving humans once were that our instinctive self or soul can’t relate to the way we are now. Consider the tenderness in the expression on the face of the Madonna in the drawing of the Madonna and child that was included at the beginning of the infancy stage. My soul drew that—I, my embattled conscious self, had nothing to do with it. Truly, as William Wordsworth wrote, ‘trailing clouds of glory do we come, From God [the integrated, loving, all-sensitive state], who is our home’ (Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, 1807). And people say humans have brutish, aggressive instincts! No, it’s the world we humans currently inhabit that is mad. It is just so traumatised with psychological upset that it hasn’t been able to deal with the fact that it is deeply, deeply dishonest; horrifically alienated. What did the great Spanish artist Pablo Picasso famously say about his ability to paint: ‘It’s taken me a lifetime to learn to paint like a child.’ And again, what did R.D. Laing say, ‘between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’. Turn on the television and find any wildlife documentary and I bet it will show pictures of crocodiles on the Mara River tearing wildebeest apart, or white sharks devouring seals, or snakes striking at the camera lens, or some equally ‘brutal’ interaction. All the beauty in nature has been reduced to representations of butchery and horror because we humans have become so upset that all we can cope with are pictures of animals ‘being’ as aggressive as we are—everything else in nature is far too confronting. I have been to natural Africa and seen its spectacle, and the sheer magic of it surpasses all imaginings; it is just achingly beautiful, the most sacred realm on Earth—‘sublime amnesia’ are the only words I can think of to describe it and they don’t even make sense. In 1992, Annie and I were fortunate enough to join a small reconnaissance party that was being sent in on foot into the northern end of the Tsavo East National Park in Kenya, an area that had been shut off from the public for many years due to the prevalence of dangerously-armed poachers from Somalia. I remember sitting hidden downwind amongst the trees on the banks of the Tiva sand river there and seeing dust rise above the tree line in the shimmering midday heat and then watching as a vast herd of black Cape buffalo, led by an old crooked horn cow, quietly materialised from the bush, cautiously coming down to drink at pools in the river bed. I really felt like a spy in heaven. It was all just unbelievable. Earth at its primal, spiritual, authentic, soulful, pristine, magical very best. I think God was there beside us sitting on his heels like a little Bushman smiling at all that he had created. That visit to the Tiva river remains the highlight of my life. With our sophisticated communication technology, why oh why don’t we have documentaries sensitively immersing us in all of that. It is so sad. We haven’t been able to cope with any truth. Our world has shrunk to the size of a pea. All the beauty and magic that is out there escapes us, we don’t see it; worse, we don’t want to see it. No wonder our soul can’t relate to us and just draws stick figures with weird blobs for faces.

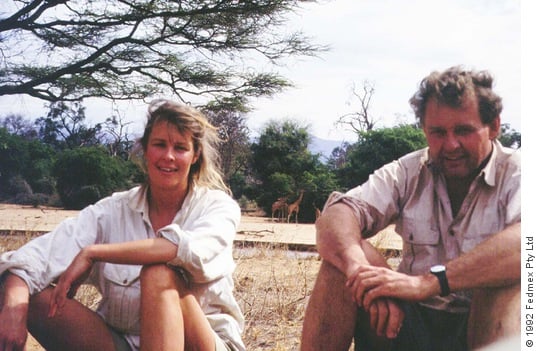

Annie Williams and I in Samburu National Park in Kenya in 1992. Those giraffes behind us are just walking around as free as a daisy. In natural Africa, animals like giraffes and elephants and rhinoceroses (well, terrifyingly, there are actually almost no rhinos left!) aren’t in cages; there are no fences over there. Animals—and the place is teeming with them, all sorts of weird shapes and sizes—just walk all around the place. It’s amazing. They can go wherever they want. They can stop here for a while and then go over the hill if they want to. They just mooch about everywhere; walk around a bush and there is another one, this time with great spiral horns coming out of the top of its head, big eyes looking at you as if to say, ‘So, who are you, what’s your problem?’ ‘My problem! Have you had a look at what’s coming out the top of your head!?’ It takes some getting used to I can tell you. I don’t know who made them all, and was he just having fun making them all in such weird and different shapes—and, more to the point, who let them all out!

Yes, humans now are immensely alienated, extremely psychologically separated from our true self or soul. Similar to what happens when I draw, in my writing I have also learnt to, as I describe it, ‘think like a stone’, or ‘think like a child’—say the simplest, most elementary thought—because I learnt that such a thought will be the most truthful and accurate and accountable and explanatory. Absolutely every time I encounter a problem I have to solve in my thinking about the human condition I go into a routine where I say to myself, ‘Just go into yourself and think like a stone, just let the truth come out that’s within and you will have the answer.’ Basically, I learnt to trust in and take guidance from my truthful instinctive self or soul. I learnt to think honestly, free of alienated, intellectual bullshit, and all the answers, all the insights that I have found, and there are many hundreds of them, a breakthrough insight in almost every paragraph, were found this way. I have so perfected the art of thinking truthfully and thus effectively that you can put any problem or question in front of me to do with human behaviour and I can get to the bottom of it, answer and solve it. It has been astonishing to me to watch my mind work, the freedom it has and where it is capable of going in its thinking. It wears me out keeping up with it. This wearing out problem is especially so because there is so much suffering in the world that simply has to be brought a stop to. Yes, I know that every sentence I write is truth-laden, in complete contrast to the billions of sentences being churned out every second everywhere else on Earth. It is the innocent instinctive child in us that knows the truth. Christ, as usual, put it perfectly when he said, ‘you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children’ (Bible, Matt. 11:25). A comment that was mentioned in par. 240 by George Seaver reiterates what I have just said about natural thinking: ‘The ultimate thought, the thought which holds the clue to the riddle of life’s meaning and mystery, must be the simplest thought conceivable, the most natural, the most elemental, and therefore also the most profound.’ Yes, as Plato was recorded as saying in par. 679, when we use our intellect with its preoccupation with denial ‘for any inquiry…it is drawn away by the body into the realm of the variable, and loses its way and becomes confused and dizzy, as though it were fuddled [drunk]…But when it investigates by itself [free of intellectual denial/bullfuckingshit], it passes into the realm of the pure and everlasting.’

The human condition has certainly been a cruel incursion. It was bad enough to have acquired a fully conscious brain, the marvellous computer we have on our heads, and not be given the program for it and instead be left to wander this planet searching for that program/understanding in a terrifying darkness of confusion and bewilderment, most especially about our worthiness or otherwise as a species, but to then be disconnected from access to the integrative, Godly, cooperatively orientated, all-loving and all-sensitive, ideal world of our original instinctive self or soul—having to block it out because it unjustly condemned us—means we have been enduring an extraordinarily lonely, sad, soul-destroyed, alienated existence! We have had to put on a brave, positive face to carry on with our horribly upsetting job of searching for knowledge, ultimately for self-knowledge, but that is the true description of our existence during that search. It follows then that it became a matter of great urgency for the increasingly upset human race to find ways to cope with such a torturous and lonely existence.

While upset was rapidly increasing through humanity’s adventurous adolescence stage and beyond, we eventually became so horrifically alienated from our all-loving and all-sensitive true self or soul that a way simply had to be found to reconnect with it. We had to find a way back to some purity and sanity, but in a safely non-confrontational manner, and one of the ways we managed to do so was by creating one of the earliest forms of religion, which was ANIMISM AND NATURE WORSHIP—religion being the strategy of putting our faith in, deferring to, and looking for comfort, reassurance and guidance from something other than our overly upset and overly soul-estranged conscious thinking egoic self. Unlike our upset soul-destroyed self, the natural world remained in an innocent state, and since nature was also associated with our original instinctive self because our species grew up with nature, it could also reconnect us to the innocent, true world of our soul. So, despite our upset state’s often violent repudiation of nature’s condemning innocence, nature could still link us back to repressed ‘spiritual’, soul-infused sensitivities, feelings and awarenesses within us that we had lost access to. Again, we see the two-sided aspect of innocence: it could condemn us and hurt us terribly, but it could also heal and inspire us.

Another way that eventually developed to counter the loneliness of our situation, and this was also one of the earliest forms of religion, was ANCESTOR WORSHIP. Having managed to survive our mind’s loneliness and our soul’s estrangement, our ancestors were a source of great reassurance and comfort. In our uncertainty and distress, we could look to them for the hope that we too might survive the horror of life under the duress of the human condition. We could look to them for ‘spiritual’ guidance, for inspiration for our troubled minds. If we tried to imagine how they coped and what they would have done in situations that we now faced, we could be inspired to reach potentials within ourselves that our troubled minds might not otherwise have allowed us access to. By revering them and enshrining their memories, our ancestors could remain a presence in our lives to look after and guide us.

Of course in addition to the practical need for inspired guidance from our ancestors, we also wanted to perpetuate our love for them and theirs for us. Humans now are so toughened—so soul-destroyed—by the levels of anger, egocentricity and alienation in human life today that it is hard for us to imagine how loving and empathetic humans once were, but the truth is the emotional need to put flowers on the graves of those ‘near to us’ would have been so much stronger and purer in earlier times when humans were stronger and purer in soul. The emotion of love would have been so powerful that everyone would have been ‘near to us’ and remained ‘near to us’ after they died. A truly loving universe is such a different universe to the one we inhabit now. Basically people didn’t ‘die’ in earlier times—they died physically of course, but their entire spirit lived on with us. Love and feeling and emotion and togetherness was everywhere and in everyone—as Hesiod was recorded as describing life before the ‘fall’ in par. 180, ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind / Nor e’er decrepit age misshaped their frame…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…Dying they sank in sleep, nor seemed to die’. It is only the extremely alienated disconnection from our all-sensitive and all-loving soul in humans of more recent times that has left us needing to believe in a physical ‘afterlife’—needing to construct pyramids as a vehicle to supposedly carry us on to another life after we died, or needing to hold onto a belief in reincarnation, etc, etc. But it is love, and our love of love, that is what is truly universal and eternal/everlasting/immortal. So it wasn’t so much ancestor worship that humans once practised but ancestor love. For instance, Stonehenge in Britain (and other such similar sacred sites) would have originally been a place to let all the love of, and from, our ancestors not only look after us but surround and embrace us, and we them in return. Likewise, the big old oak trees that the druids revered were similarly sacred beings that were ‘near to us’ when we were still open to the loving life that they were so full of. Love (which, as explained in chapter 4, is the unconditionally selfless theme of the integration of matter) was everywhere we walked, but as humans became more upset and alienated we began to need to create places like Stonehenge and sacred groves of oak trees to remind ourselves of that loving, connected state. Later, however, as upset and alienation became even more extreme, the deeper sensitivities of our soul became more and more inaccessible, so that nowadays there is no real spirituality left in life, only festivals of fake, imitated spirituality and sensitivity. This state of terminal alienation is one of the main subjects of the latter part of this book. (I should explain that having said that unconditionally selfless love is everywhere and that nature, such as oak trees, are full of loving life, we, of course, have always been aware that there is conflict in nature, that animals especially fight with and kill each other, but we considered that this occurs because living things sometimes, in effect, lose sight of love. In fact, we were aware that many animals struggle to be loving and can only manage it for periods, and so we forgave them for that—‘there’s my unfortunate friend Mr Crocodile, dressed in armour, anticipating, even provoking battle, and with a massive extended mouth full of ferocious teeth, lying there in the swamp ready to tear to pieces any creature that comes close’. Love is everywhere even though some creatures struggle to, in effect, appreciate it. [This truth that we once knew was explained in chapter 4 when the integrative limitation of the gene-based natural selection process that produced the competition and aggression we see in nature was described.] In more innocent times, we were magnanimous towards the sometimes divisive behaviour that occurs in nature, such as in our animal friends, because we could feel and see the greater truth that love is universal; that it is the one fabulously wonderful, great force in the world. Again, this was before the upset state of the human condition became so developed that our shame killed off this awareness, at which point we invented all manner of false truths or ‘gods’, such as gods for war, and for sexual love, and for imperfections that we no longer had the generosity of spirit to cope with—such as gods for lack of rain, and for violent weather. And once these multiple gods were invented it took a long time, and some exceptionally sensitive, soulful thinkers, such as Abraham, to return us to the truth that there is only one God—love or unconditional selflessness.)

Alongside the development of these spiritual supplements, humans were also becoming more technologically advanced. For instance, tools including sharpened stones, choppers, hand axes and scrapers, cudgels, spears, harpoons and bone needles appear in the archaeological record from 3.3 million years onwards, while there is evidence that H. erectus (who lived some 1.9 to 0.1 million years ago) made refined tear-drop shaped flint axe heads and that even the earliest of this variety of humans were using fire (as indicated by the remnants of hearths at Koobi Fora in Kenya). However, it is only within the final 14,000 of the 2 million years of humanity’s adolescence that the most dramatic improvements occurred. It was during this period that the bow and arrow, fish basket traps and crude boats first appeared, while the practice of agriculture and the domestication of animals, which both began around 11,000 years ago, brought with it the production of earthenware pottery, looms, hoes, ploughs and reaping-hooks. (This acceleration of technology can be seen in the relatively swift succession between the great ages that define our modern history, with the Stone Age being replaced around 5,000 years ago by the Bronze Age, which in turn was replaced around 3,000 years ago by the Iron Age.)

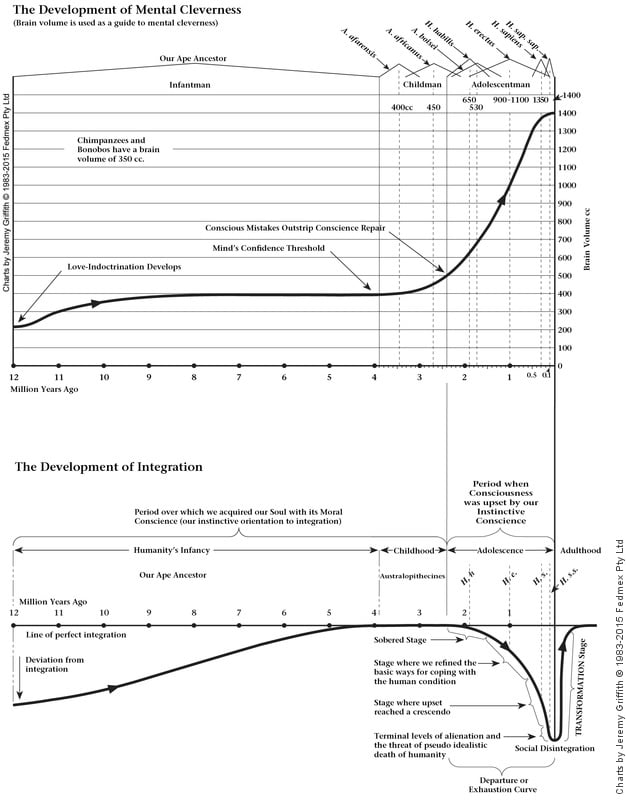

It needs to be emphasised that throughout these epochs of time the whole development of upset was being driven by increasing levels of intelligence, and vice versa; this is because the more intelligent we were, the more we searched for understanding, and the more we engaged in that corrupting, soul-destroying search, the more upset we became—and with each new level of upset, a new psychological and accompanying physical existence and state emerged, including increased alienation. The following two graphs chart the psychological journey that humanity has been on, with the top graph charting the development over time of mental cleverness, as indicated by brain volume, and the bottom graph charting the development of cooperativeness or integration.

We can see that while the brain size of ‘Childman’ (the australopithecines) was not much bigger than ‘Infantman’ (represented today by species such as chimpanzees and bonobos), a sudden increase in brain size occurred with the emergence of the first ‘Adolescentman’, H. habilis, when the need to think and understand began in earnest as a result of the emergence of the dilemma of the human condition. This dramatic growth continued through ‘Adventurous Adolescentman’ (H. erectus) and ‘Angry Adolescentman’ (H. sapiens) before finally plateauing with ‘Pseudo Idealistic and Hollow Adolescentman’ (H. sapiens sapiens). Anthropologists have long wondered why this growth stopped in the last 200,000 years or so. The reason is that in ‘Pseudo Idealistic and Hollow Adolescentman’ a balance was struck between the need for cleverness and the need for soundness; between knowledge-finding yet corrupting mental cleverness and conscience-obedient yet non-knowledge-finding lack of mental cleverness, with the average IQ today representing that relatively safe conscience-subordinate, not overly upset, not too selfish, egocentric and dysfunctional, compromise. Conscious mental cleverness is what caused us to challenge our instincts, the result of which was we became corrupted in soul, so it follows that the more mentally clever we humans became, the more corrupted in soul we also became, and that eventually we became too clever and too corrupted. Cleverness and alienation have been related. That has been the elementary truth about the human condition.

The bottom graph, which indicates the development of cooperativeness or integration, shows that by 5 million years ago nurturing had enabled our ancestors to live in an utterly cooperative state. However, with conscious self-management, and with it the upsetting battle of the human condition, becoming fully developed some 2 million years ago, we see that the graph marks a rapid increase in upset from that time to the present, where we now face the prospect of terminal levels of alienation and social dis-integration.