‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 2 The Threat of Terminal Alienation from Science’s Denial

Chapter 2:2 The psychological event of ‘Resignation’ reveals our species’ mortal fear of the human condition and thus how difficult it has been for scientists to find the explanation of the human condition and make sense of human behaviour

To briefly recount the description given in chapter 1 of what the human condition really is, it is worth reciting the incisive words of the polymath Blaise Pascal, who spelled out the full horror of our contradictory condition when he wrote, ‘What a chimera then is man! What a novelty, what a monster, what a chaos, what a contradiction, what a prodigy! Judge of all things, imbecile worm of the earth, repository of truth, a sewer of uncertainty and error, the glory and the scum of the universe!’ Shakespeare too was equally revealing of what the human condition really is when he wrote, ‘What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason! How infinite in faculty!…In action how like an angel! In apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world! The paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? [Brutal and barbaric] Man delights not me’. Pascal’s and Shakespeare’s identification of the dichotomy of ‘man’ is what the human condition really is—this most extraordinary ‘contradiction’ of being the most brilliantly clever of creatures, the ones who are ‘god’-‘like’ in our ‘infinite’ ‘faculty’ of ‘reason’ and ‘apprehension’, and yet also the meanest, most vicious of species, one that is only too capable of inflicting pain, cruelty, suffering and degradation. Yes, the eternal and seemingly unanswerable question has been: are we ‘monster[s]’, the ‘essence’ of ‘dust’, ‘the scum of the universe’, or are we a wonderful ‘prodigy’, even ‘glor[ious]’ ‘angel[s]’?

Thankfully, as was outlined in chapter 1, we can at long last now explain and understand that we are not, in fact, ‘monster[s]’ but ‘glor[ious]’ heroes. However, having had to live without this reconciling and dignifying understanding has meant that each human growing up under the duress of the human condition has suffered from immense insecurity about their fundamental goodness, worth and meaningfulness. So much so that the more we tried to think about this, in truth, most obvious question of our meaningfulness and worthiness (or otherwise), the more insecure and depressed our thoughts became. The emotional anxiety produced when reading Pascal’s and Shakespeare’s descriptions of the human condition gives some indication of just how unnervingly confronting the issue of the human condition really is. The truth, that will now be revealed, is that this intensely personal yet universal issue of the human condition has been so unbearably confronting and depressing that we eventually learnt as we grew up that we had no choice but to resign ourselves to never revisiting the subject, to never again looking at the seemingly inexplicable issue of the human condition. The examination of this process of what I call ‘Resignation’ to living in Plato’s dark cave of denial of the human condition, and how it unfolds, will reveal just how immensely fearful humans have been of the human condition, and, it follows, how impossible it has been for mechanistic scientists to think effectively about human behaviour.

As will be explained in detail in chapter 8, as humans grew up in a human-condition-afflicted world that wasn’t able to be truthfully analysed and explained, we each became increasingly troubled by the glaringly obvious issue of the extreme ‘imperfections of human life’ (as Plato referred to ‘our human condition’). This progression went through precise stages—and I should point out that all these stages of resignation to a life of blocking out the issue of the human condition have not been admitted by science, because like almost every other human, its practitioners have also lived in mortal fear and thus almost total denial of the human condition. What follows then is a very brief summary of the life stages that will be fully described in chapter 8.

As consciousness emerged in humans we progressed from being able to sufficiently understand the relationship between cause and effect to become self-conscious, aware of our own existence, during our infancy, to proactively carrying out experiments in self-management during our childhood, at which point all the manifestations of the human condition of anger, egocentricity and alienation began to reveal themselves. It follows that it was during our childhood that we each became increasingly aware of not only the imperfection of the human-condition-afflicted world around us, but of the imperfection of our own behaviour—that we too suffered from anger, selfishness, meanness and indifference to others. Basically, all of human life, including our own behaviour, became increasingly bewildering and distressing, to such a degree that by the time children reached late childhood they generally entered what is recognised as the ‘naughty nines’, where their confusion and frustration was such that they even angrily began taunting and bullying those around them. By the end of childhood, however, children realised that lashing out in exasperation at the imperfections, wrongness and injustice of the world didn’t change anything and that the only possible way to end their frustration was to understand why the world, and their own behaviour, was not ideal. It was at this point, which occurred around 12 years of age, that children underwent a dramatic change from being frustrated, protesting, demonstrative, loud extroverts into sobered, deeply thoughtful, quiet introverts, consumed with anxiety about the imperfections of life under the duress of the human condition. Indeed, it is in recognition of this very significant psychological transition from a relatively human-condition-free state to a very human-condition-aware state that we separate these stages into ‘Childhood’ and ‘Adolescence’, a shift even our schooling system marks by having children graduate from what is generally called primary school into secondary school. What then happened during adolescence was that, at about 14 or 15 years of age and after struggling for a few years to make sense of existence, the search for understanding became so confronting of those extreme internal imperfections that adolescents had no choice but to ‘Resign’ to living in denial of the whole unbearably depressing and seemingly unsolvable issue of the human condition—after which they became superficial and artificial escapists, not wanting to look at any issue too deeply, and, before long, combative and competitive power-fame-fortune-and-glory, relief-from-the-agony-and-guilt-of-the-human-condition-seeking resigned adults.

Delving deeper into how the journey toward ‘Resignation’ unfolds will reveal just how terrifying the issue of the human condition has been, which is precisely what the reader needs to become aware of in order to appreciate why it has, until now, been impossible to truthfully and thus effectively explain human behaviour. Yes, describing what occurs at ‘Resignation’ makes it abundantly clear why resigned humans became so superficial and artificial in their thinking, incapable of plumbing the great depths of the human condition and thus incapable of finding the desperately needed understanding of human existence.

So what happened at around 14 or 15 years of age for virtually all humans growing up under the duress of ‘the imperfections’ of ‘our human condition’ was that to avoid the suicidal depression that accompanied any thinking about the issue of our species’, and our own, seemingly extremely imperfect condition, there was simply no choice but to stop grappling with the answerless question. And so despite the human condition being the all-important issue of the meaningfulness or otherwise of our existence, there came a time (and, although it varies according to each individual’s circumstances, it typically occurred at about 14 or 15 years of age) when adolescents were forced to put the whole depressing subject aside once and for all and just hope that one day in the future the explanation and defence for our species’, and thus our own, apparently horrifically flawed, seemingly utterly disappointing, sad state would be found, because then, and only then, would it be psychologically safe to even broach the subject. In 2010 a poignantly honest film titled It’s Kind Of A Funny Story (based on Ned Vizzini’s book of the same title) was made about a 16-year-old boy named Craig who is going through the agonising process of grappling with the human condition; he struggles with ‘suicidal’ ‘depression’ from ‘anxiety’ about ‘grades, parents [who don’t seem to have ‘a clue’ that ‘there’s something bigger going on’], two wars, impending environmental catastrophe, a messed up economy’. Eventually a psychiatrist counsels him that ‘there is a saying that goes something like this: “Lord, grant me the strength to change the things I can, the courage to accept the things I can’t, and the wisdom to know the difference”’; basically he is advised to resign himself to living in denial of the human condition. The Beatles’ song Let It Be—consistently voted one of the most popular songs of the twentieth century—is actually an anthem to this need that adolescents have historically had, when confronted with the unbearable ‘hour of darkness’ that came from grappling with the issue of all ‘the broken hearted people living in the world’, to ‘let it be’ ‘until tomorrow’ when ‘there will be an answer’ (Lennon/McCartney, 1970). So when the great poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote about the unbearably depressing subject of the human condition in his aptly titled poem No Worst, There Is None (1885), his words, ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall, frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed’, did not exaggerate the depth of depression humans faced if we allowed our minds to think about the human condition while it was still to be ‘fathomed’/understood/‘answer[ed]’. Yes, when, in ‘my hour of darkness’, ‘Mother Mary comes…speaking words of wisdom, let it be, let it be’—accept the adults’ ‘wisdom’, and don’t go there!

It’s little wonder then that the human condition has been described so vehemently as ‘the personal unspeakable’ and as ‘the black box inside of humans they can’t go near’ (personal conversations, WTM records, Feb. 1995)—and why it is so very rare to find a completely honest description of adolescents going through the excruciating process of Resignation, of resigning themselves to having to block out the seemingly inexplicable question of their worth and meaning and live, from that time on, in denial of the unbearable issue of the human condition. Having already been through this terrible process of Resignation, most adults simply couldn’t allow themselves to recall, recognise and thus empathise with what adolescents were experiencing (they were, as Craig complained, rendered ‘clue’-less to the situation). And so our young have been alone with their pain, unable to share it with those closest, or the world at large. All of which makes the following account of a teenager in the midst of Resignation, by the American Pulitzer Prize-winning child psychiatrist Robert Coles, incredibly special: ‘I tell of the loneliness many young people feel…It’s a loneliness that has to do with a self-imposed judgment of sorts…I remember…a young man of fifteen who engaged in light banter, only to shut down, shake his head, refuse to talk at all when his own life and troubles became the subject at hand. He had stopped going to school…he sat in his room for hours listening to rock music, the door closed…I asked him about his head-shaking behavior: I wondered whom he was thereby addressing. He replied: “No one.” I hesitated, gulped a bit as I took a chance: “Not yourself?” He looked right at me now in a sustained stare, for the first time. “Why do you say that?” [he asked]…I decided not to answer the question in the manner that I was trained [basically, ‘trained’ in avoiding what the human condition really is]…Instead, with some unease…I heard myself saying this: “I’ve been there; I remember being there—remember when I felt I couldn’t say a word to anyone”…The young man kept staring at me, didn’t speak…When he took out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes, I realized they had begun to fill’ (The Moral Intelligence of Children, 1996, pp.143-144 of 218). The boy was in tears because Coles had reached him with some recognition and appreciation of what he was wrestling with; Coles had shown some honesty about what the boy could see and was struggling with, namely the horror of the utter hypocrisy of human behaviour—including his own.

The words Coles used in his admission that he too had once grappled with the issue of the human condition, of ‘I’ve been there’, are exactly those used by one of Australia’s greatest poets, Henry Lawson, in his extraordinarily honest poem about the unbearable depression that results from trying to confront the question of why human behaviour is so at odds with the cooperative, loving—or, to use religious terms, ‘Godly’—ideals of life. In his 1897 poem The Voice from Over Yonder, Lawson wrote: ‘“Say it! think it, if you dare! Have you ever thought or wondered, why the Man and God were sundered [torn apart]? Do you think the Maker blundered?” And the voice in mocking accents, answered only: “I’ve been there.”’ The unsaid words in the final phrase, ‘I’ve been there’, being ‘and I’m certainly not going ‘there’ again!’—with the ‘there’ and the ‘over yonder’ of the title referring to the state of deepest, darkest depression.

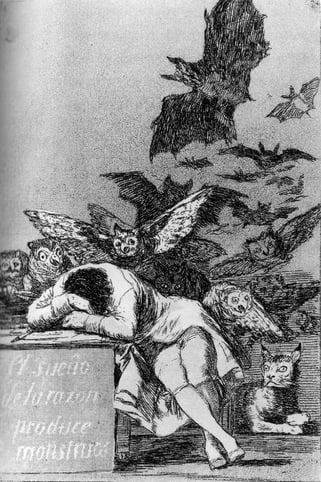

Goya’s The sleep of reason brings forth monsters, 1796-97

In his bestselling 2003 book, Goya (about the great Spanish artist Francisco Goya), another Australian, Robert Hughes, who for many years was TIME magazine’s art critic, described how he ‘had been thinking about Goya…[since] I was a high school student in Australia…[with] the first work of art I ever bought…[being] a poor second state of Capricho 43…The sleep of reason brings forth monsters…[Goya’s most famous etching reproduced above] of the intellectual beset with doubts and night terrors, slumped on his desk with owls gyring around his poor perplexed head’ (p.3 of 435). Hughes then commented that ‘glimpsing The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was a fluke’ (p.4). A little further on, Hughes wrote of this experience that ‘At fifteen, to find this voice [of Goya’s]—so finely wrought [in The sleep of reason brings forth monsters] and yet so raw, public and yet strangely private—speaking to me with such insistence and urgency…was no small thing. It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it’ (p.5). Again, while the process of Resignation is such a horrific experience that adults determined never to revisit it, or even recall it, Hughes’ attraction to The sleep of reason brings forth monsters was not the ‘fluke’ he thought it was. The person slumped at the table with owls and bats gyrating around his head perfectly depicts the bottomless depression that occurs in humans just prior to resigning to a life of denial of the issue of the human condition, and someone in that situation would have recognised that meaning instantly, almost wilfully drawing such a perfect representation of their state out of the world around them. Even the title is accurate: ‘The sleep of reason’—namely letting down our mental guard—does ‘bring forth monsters’! While Hughes hasn’t recognised that what he was negotiating ‘At fifteen’ was Resignation, he has accurately recalled how strongly he connected to what was being portrayed in the etching: ‘It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: this is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it.’ Note how Hughes’ words, ‘I have been through it’, are almost identical to Coles’ and Lawson’s words, ‘I’ve been there.’

And so, unable to acknowledge the process of Resignation, adults instead blamed the well-known struggles of adolescence on the hormonal upheaval that accompanies puberty, the so-called ‘puberty blues’—even terming glandular fever, a debilitating illness that often occurs in mid-adolescence, a puberty-related ‘kissing disease’. These terms, ‘puberty blues’ and ‘kissing disease’, are dishonest, denial-complying, evasive excuses because it wasn’t the onset of puberty that was causing the depressing ‘blues’ or glandular fever, but the trauma of Resignation. For glandular fever to occur, a person’s immune system must be extremely rundown, and yet during puberty the body is physically at its peak in terms of growth and vitality—so for an adolescent to succumb to the illness they must be under extraordinary psychological pressure, experiencing stresses much greater than those that could possibly be associated with the physical adjustments to puberty, an adjustment, after all, that has been going on since animals first became sexual. No, the depression and glandular fever experienced by young adolescents are a direct result of the trauma of having to resign to never again revisiting the unbearably depressing subject of the human condition. (Note, other dishonest excuses for teen angst are described in Freedom Essay 30 on the WTM home page.)

That sublime classic of American literature, J.D. Salinger’s 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye, is a masterpiece because, like Coles, Salinger dared to write about that forbidden subject for adults of adolescents having to resign to a dishonest life of denial of the human condition—for The Catcher in the Rye is actually entirely about a 16-year-old boy struggling against Resignation. The boy, Holden Caulfield, complains of feeling ‘surrounded by phonies’ (p.12 of 192) and ‘morons’ who ‘never want to discuss anything’ (p.39), of living on the ‘opposite sides of the pole’ (p.13) to most people, where he ‘just didn’t like anything that was happening’ (p.152), to wanting to escape to ‘somewhere with a brook…[where] I could chop all our own wood in the winter time and all’ (p.119). He knows he is supposed to resign—in the novel he talks about being told that ‘Life…[is] a game…you should play it according to the rules’ (p.7), and to feeling ‘so damn lonesome’ (pp.42, 134) and ‘depressed’ (multiple references) that he felt like ‘committing suicide’ (p.94). As a result of all this despair and disenchantment with the world he keeps ‘failing’ (p.9) his subjects at school and is expelled from four for ‘making absolutely no effort at all’ (p.167). About his behaviour he says, ‘I swear to God I’m a madman’ (p.121) and ‘I know. I’m very hard to talk to’ (p.168). But like the boy in Coles’ account, Holden finally encounters some rare honesty from an adult that, in Holden’s words, ‘really saved my life’ (p.172). This is what the adult said: ‘This fall I think you’re riding for—it’s a special kind of fall, a horrible kind…[where you] just keep falling and falling [utter depression]’ (p.169). The adult then spoke of men who ‘at some time or other in their lives, were looking for something their own environment couldn’t supply them with…So they gave up looking [they resigned]…[adding] you’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior’ (pp.169-170). Yes, to be ‘confused and frightened’ to the point of being ‘sickened by human behavior’—indeed, to be ‘suicid[ally]’ ‘depressed’ by it—is the effect the human condition has if you haven’t resigned yourself to living a relieving but utterly dishonest and superficial life in denial of it. (For more on the devastating effects of the human condition and the resigned world on the minds of those who have not resigned, see par. 988.)

Going through Resignation has been a truly horrific experience. A friend and I were walking in bushland past a school one day when we came across a boy, who would have been about 14 years old, sitting by the track in a hunched, foetal position. When I asked him if he was okay he looked up with such deep despair in his eyes that it was clear he didn’t want to be disturbed and so we left him alone. It was very apparent that he was trying to wrestle with the issue of the human condition, but without understanding of the human condition it hasn’t been possible for virtually all humans to do so without becoming so hideously condemned and thus depressed that they had no choice but to eventually surrender and take up denial of the issue of the human condition as the only way to cope with it—even though doing so meant adopting a completely dishonest, superficial and artificial, effectively dead, existence.

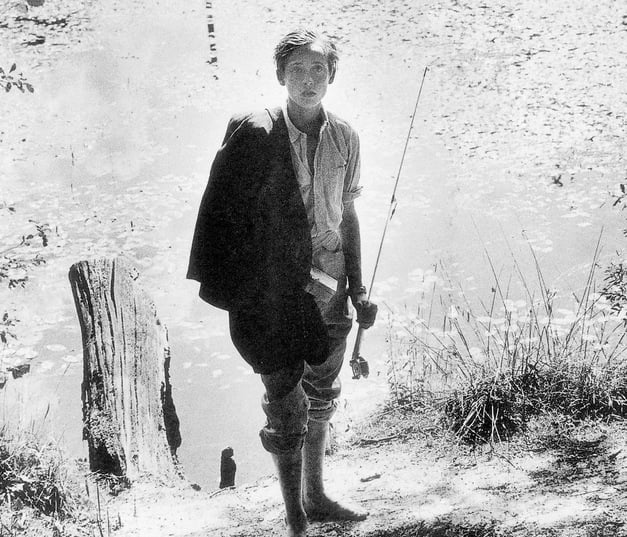

Images of adolescents in the midst of Resignation used to be difficult to find, but I have recently found many pictures of adolescents in that state in Google Images using the search terms ‘teen angst’ and ‘teen depression’, some of which I’ve included in Freedom Essay 30 on the WTM website. Previously I relied upon the following haunting image of a boy who had, the previous day, lost all his classmates in a plane crash, and his expression is exactly the same deeply sobered, drained pale, all-pretences-and-facades-stripped-away, pained, tragic, stunned, human-condition-laid-bare expression I have seen on the faces of adolescents going through Resignation. We can see in this boy’s face that all the artificialities of human life have been rendered meaningless and ineffectual by the horror of losing all his friends, leaving bare only the sad, painful awareness of a world devoid of any real love, meaning or truth.

‘Too poor to go on school trip, boy fishes the day after classmates perish in plane crash’

LIFE magazine, Fall Special Edition, 1991

Although rarely shared, adolescents in the midst of Resignation quite often write excruciatingly honest poetry about their impending fate; indeed, The Catcher in the Rye is really one long poem about the agony of having to resign to living a human-condition-denying, superficial, totally false existence. I have written much more about Resignation at <www.humancondition.com/freedom-expanded-resignation>, however, the following are two horrifically honest Resignation poems that are discussed at that link and worth including here to provide first-hand insights into the agony of adolescence: ‘You will never have a home again / You’ll forget the bonds of family and family will become just family / Smiles will never bloom from your heart again, but be fake and you will speak fake words to fake people from your fake soul / What you do today you will do tomorrow and what you do tomorrow you will do for the rest of your life / From now on pressure, stress, pain and the past can never be forgotten / You have no heart or soul and there are no good memories / Your mind and thoughts rule your body that will hold all things inside it; bottled up, now impossible to be released / You are fake, you will be fake, you will be a supreme actor of happiness but never be happy / Time, joy and freedom will hardly come your way and never last as you well know / Others’ lives and the dreams of things that you can never have or be part of, will keep you alive / You will become like the rest of the world—a divine actor, trying to hide and suppress your fate, pretending it doesn’t exist / There is only one way to escape society and the world you help build, but that is impossible, for no one can ever become a baby again / Instead you spend the rest of life trying to find the meaning of life and confused in its maze’; and another Resignation poem: ‘Growing Up: There is a little hillside / Where I used to sit and think / I thought of being a fireman / And of thoughts, I thought important / Then they were beyond me / Way above my head / But now they are forgotten / Trivial and dead.’

Yes, as these poems so painfully express, Resignation means blocking out all memory of the innocent, soulful, true world because it is unbearably condemning of our present immensely corrupted human condition: ‘You have no heart or soul and there are no good memories / Your mind and thoughts rule your body that will hold all things inside it; bottled up, now impossible to be released / You are fake, you will be fake, you will be a supreme actor of happiness but never be happy.’ And since virtually all adults have resigned, that is exactly how ‘fake’, or as the 16-year-old Holden Caulfield described it, ‘phony’, they have become. Clearly, the price of Resignation is enormous, but the alternative for virtually all humans of not resigning has been an even worse fate because it meant living with constant suicidal depression.

Appreciably then, in what forms the key passage in The Catcher in the Rye (indeed, it provides the meaning behind the book’s enigmatic title), Salinger has Holden Caulfield dreaming of a time when this absolute horror, indeed obscenity, of Resignation will no longer have to form an unavoidable part of human life: ‘I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be’ (p.156). And, as will be explained in this book, the time that Holden Caulfield so yearned for when we will be able to ‘catch’ all children before ‘they start to go over the [excruciating] cliff’ of Resignation to a life of utter dishonesty, ‘phony’, ‘fake’ superficiality, and silence in terms of ‘never want[ing] to discuss anything’ truthfully again, has finally come about with the finding of the all-clarifying, redeeming and relieving truthful, fully compassionate explanation of human behaviour! Yes, the real ‘catcher in the rye’ is the ability to explain ‘human behavior’ so that it is no longer ‘sicken[ing]’ but understandable, and, best of all, healable.