‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 5 The Origin of Humans’ Moral Instinctive Self or Soul

Chapter 5:9 Sexual selection for integrativeness explains neoteny

Yes, since it is the males who are the most preoccupied with competing for mating opportunities, the females must have been the first to select for selfless, cooperative integrativeness by favouring integrative rather than competitive and aggressive mates—and it was this process of the conscious self-selection of integrativeness, especially the sexual selection of less aggressive males with whom to mate, that greatly helped love-indoctrination subdue the males’ divisive competitiveness. Moreover, by seeking out less aggressive, more integrative mates, the females were, in effect, selecting those who have been the most love-indoctrinated. This raises the next point to be explained, which is that the most love-indoctrinated and thus most integrative individuals will be those who have experienced a long infancy and exceptional nurturing and are closer to their memory of their love-indoctrinated infancy; specifically, those that are younger. The older individuals became, the more their infancy training in love wore off. In the case of our ape ancestors, they began to recognise that the younger an individual, the more integrative he or she was likely to be and, as a result, began to idolise, foster, favour and select for youthfulness because of its association with cooperative integration. The effect, over many generations, was to retard physical development so that adults became more infant-like in their appearance—which explains how we first came to regard neotenous (infant-like) features, like large eyes, dome forehead, snub nose and hairless skin, as beautiful and attractive.

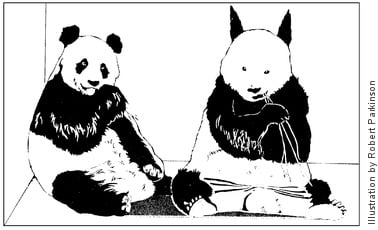

Consider, for instance, the neotenous or infant-like large eyes of seal pups and frogs, and the large eye spot markings together with the soft, typically infant-like, moppish ears of giant pandas—they are what make these animals so ‘appealing’. The following drawing of a panda depicted without its trademark spotted eyes and round ears, and with pricked ears and small eyes instead, shows just how quickly it loses its ‘cute’ appeal.

‘Would we care if they weren’t so cute? White out the black eye spots

and give the ears points, and the panda loses much of its appeal’

Good Weekend, The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Sep. 1989

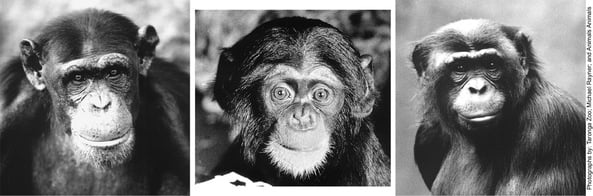

To indicate the effects of the love-indoctrination, mate selection neotenising process, I have assembled the following photographs of infant and adult non-human primates, specifically bonobos and chimpanzees.

Firstly, the following three photographs, of an adult chimpanzee, an infant chimpanzee and an adult bonobo, show the similarity between the infant chimpanzee and the adult bonobo, indicating, as stated, the effects of the love-indoctrination, mate selection neotenising process.

In addition to their remarkably neotenous physical appearance, there is also a marked variance in features between individual bonobos (which is also apparent in the very different facial features of the two bonobos pictured standing upright earlier, after par. 413), suggesting the species is undergoing rapid change. This in turn suggests that the bonobo species has hit upon some opportunity that facilitates a rapid development, which evidence indicates is the ability to develop integration through love-indoctrination and mate selection.

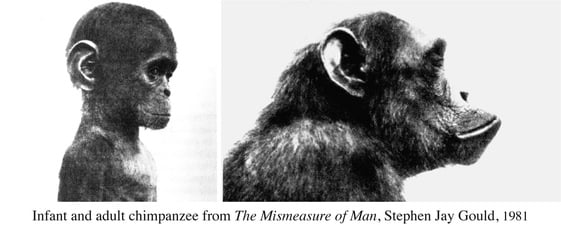

The photographs below of an infant and adult chimpanzee also show the greater resemblance humans have to the infant, again illustrating the effect of neoteny in human development.

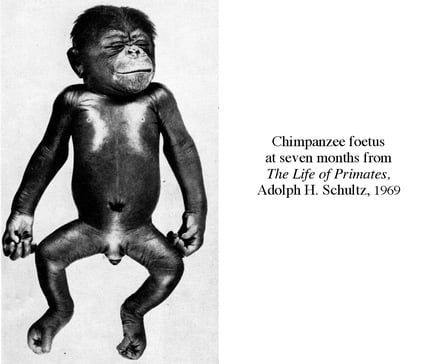

And finally, the following photograph of a chimpanzee foetus at seven months shows body hair on the scalp, eyebrows, borders of the eye lids, lips and chin—precisely those regions where hair is predominantly retained in adult humans today, again illustrating the effect of neoteny or pedomorphosis in human development. (‘Pedomorphosis’ comes from the Greek pais, meaning ‘child’, and morphosis, meaning ‘shaping’.) Clearly, humans are an extremely neotenised—love-indoctrinated—ape. Interestingly, a report on the fossilised remains of our 4.4-million-year-old ancestor Ar. ramidus describes it as having a ‘short face and weak prognathism [projecting jaw] compared with the common chimpanzee’ (Gen Suwa et al., ‘The Ardipithecus ramidus Skull and Its Implications for Hominid Origins’, Science, 2009, Vol.326, No.5949), indicating that this physical retardation or neotenisation was well underway by this point in our ancestral history.

So, we humans did learn to recognise that the older individuals became, the more their infancy training in love wore off and, therefore, the younger an individual, the more integrative he or she would likely be, and it was this selection for youthfulness that had the effect of retarding our development so that we became more infant-like in our appearance as adults. As stated, this was how we came to regard neotenous features—large eyes, dome forehead, snub nose and hairless skin—as attractive.