‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 3 The Real Explanation of The Human Condition

Chapter 3:3 The psychosis-addressing-and-solving real explanation of the human condition

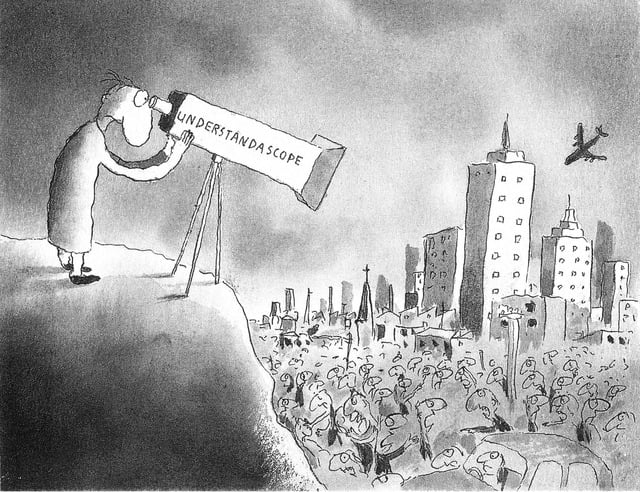

In another brilliant cartoon (below), Michael Leunig succinctly dares to ask the fundamental question of ‘What does the chaotic, traumatic and strife-torn life of humans all mean—how are we to make sense of our existence?’ He has done so by placing a very perplexed and distressed gentleman behind an ‘Understandascope’, through which he peers into a sea of apparent madness. Everywhere he looks there is tumultuous congestion: there are people furiously arguing and fighting with each other; there is a church where people pray for forgiveness and salvation; and there are vehicles polluting the chaos with fumes and noise. And, in this 1984 drawing Leunig even seems to have predicted a climactic demonstration of all our human excesses and frustrations when, on September 11, 2001, terrorists flew planes into the tall, square-shaped towers of the World Trade Center in New York City! Well, it is precisely this great burning, searing question of ‘What is wrong with us humans?’—‘How are we to understand it all?’—‘How are we to make sense of human existence?’—that is now going to be answered here. The explanation to be given here in full is the ‘UNDERSTANDASCOPE’ we have always wanted, needed and sought.

As emphasised in chapter 2, to provide this all-exciting, human-race-liberating, amazingly simple, fully accountable, true explanation of the human condition requires starting from the unequivocally honest basis of acknowledging that humans did once live in a completely loving, unconditionally selfless, altruistic state, and that it was only after the emergence of our conscious mind that our present ‘good-and-evil’-afflicted, immensely psychologically upset condition emerged. If we do this and consider what would happen when a conscious mind emerged in the presence of an already established cooperative, loving instinctive state—given what human-condition-avoiding, mechanistic science has managed to discover about the gene-based natural selection process and how nerves are capable of memory—then the explanation is right there in front of us.

Clearly, since our altruistic, moral instincts are only genetic orientations to the world and not understandings of it, when our fully conscious, reasoning, self-managing mind emerged it would, in order to find the understandings it needed to effectively manage events, have had to challenge those innate, born-with, genetic instinctive orientations, which would have led to a psychologically upsetting clash with our moral instincts.

The exceptionally ‘clear conscience’-guided, truthful, and thus effective-thinking, ‘prophetic’ naturalist Eugène Marais was on the right track when, as mentioned in par. 187, he recognised that ‘As the…individual memory slowly emerges [in humans], the instinctive soul becomes just as slowly submerged…For a time it is almost as though there were a struggle between the two.’ Berdyaev was also approaching the truth when, as just mentioned, he wrote that ‘The human soul is divided, an agonizing conflict between opposing elements is going on in it…the distinction between the conscious and the subconscious mind is fundamental for the new psychology.’ Other thinkers, such as Arthur Koestler, Erich Neumann, Paul MacLean, Julian Jaynes and Christopher Booker, have also delved into the problem of the human condition to a similar depth to Marais and Berdyaev, but what was missing was the clarifying explanation of the nature of that ‘struggle’ and ‘conflict’ between our instincts and our consciousness. (After all, as pointed out in chapter 2:6, even Moses’ Genesis story of the Garden of Eden contains the truth that our corrupted, ‘fallen’ condition occurred when our conscious mind and ‘disobedient’ free will emerged from an original, presumably instinctive, idyllic state, and Plato recognised there was a conflict between ‘noble’, ‘good’ instincts, a ‘white’ ‘horse’, against an ‘ignoble’, ‘bad’, ‘crooked’, ‘unlawful deeds’-producing conscious intellect, a ‘dark’ ‘horse’, but the degree of insight apparent in these descriptions didn’t liberate humanity from the human condition.) So, yes, what is the particular ‘distinction’ between our instincts and intellect that caused the psychologically upset state of our ‘good-and-evil’-afflicted condition? As just stated, the answer is that the gene-based refinement or learning system is only capable of orientating a species, whereas the nerve-based refinement or learning system has the potential to understand the nature of change.

To present the explanation in more detail.

Firstly, to explain what instincts are. While animals largely depend on their nervous system to coordinate their movement and control how they react to their environment, other systems such as their hormonal, circulatory, digestive, immune and reproductive systems also influence how they behave. Obviously all these systems that affect how a species of animal moves and behaves have been acted on by natural selection in the course of adapting that species over many generations to its environment. It is these naturally selected genetic traits that orientate an animal’s movements and behaviour that are referred to as its instincts. Animals move about and behave in many different ways—they fight and court each other, they build nests, they search for food, they migrate, etc—and natural selection has given them genetic programming, ‘instincts’, to control and orientate all this movement and behaviour. Plants could be said to have instincts for the control and orientation of their behaviour, but because they don’t move about and have such constantly changing behaviour as animals, instincts for the control of movement and behaviour are more associated with animals than plants. In the case of consciousness (and this was briefly explained in par. 61), there is one aspect of nerves’ ability to control how animals react to their environment that has the potential to give rise to consciousness—and this is an aspect that is largely independent of any instinctive orientations of an animal’s nervous system that have developed through natural selection. This aspect of the nervous system that gave rise to the potential to develop a conscious understanding of cause and effect is nerves’ ability to store impressions—what we refer to as ‘memory’. An electric current passed through a nerve leaves an imprint of its passage in the nerve after the current has passed. This imprint represents a memory of that piece of information that passed through the nerve. This ability to remember past events makes it possible to compare them with current events and identify regularly occurring experiences. This knowledge of, or insight into, what has commonly occurred in the past makes it possible to predict what is likely to happen in the future and to adjust your behaviour accordingly. Once insights into the nature of change are put into effect, the self-modified behaviour starts to provide feedback, refining the insights further. Predictions are compared with outcomes and so on. Much developed, and such refinement occurred in the human brain, nerves can sufficiently associate information to reason how experiences are related, learn to understand and become CONSCIOUS of, or aware of, or intelligent about, the relationship between events that occur through time. Thus consciousness means being sufficiently aware of how experiences are related to attempt to manage change from a basis of understanding. (I should mention that admitting the above obvious explanations of what instincts actually are and what consciousness actually is has been avoided by human-condition-avoiding mechanistic science. This is because while we couldn’t truthfully explain our corrupted human condition, any admission that we have cooperative and loving moral instincts and a conscious mind that corrupted that pure, innocent state was unbearable. And so to avoid any thought journey getting underway that might lead to those condemning realisations, the keepers of the lie (mechanistic scientists) realised it was best to stop that thought journey at the outset by claiming we just don’t know what instincts actually are and consciousness actually is. When I tried to explain my instinct vs intellect explanation of the human condition to the former Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK government, Lord Robert May, at Oxford University in 2014, he said, ‘But Jeremy, we don’t know what instincts actually are, or how we actually got them’ (WTM records, 13 Nov. 2014). Certainly instincts are somewhat complicated, but, as the explanation and description of instincts that I have just given evidences, not nearly as bewildering as May tried to make out. In the case of consciousness, chapter 7:2 describes in some detail why and how consciousness has been deliberately left cloaked in mystery and confusion. Chapter 7 also explains much more about the nature of consciousness, and also how we humans managed to become conscious when other animals haven’t.)

So while the ‘gene-based learning system’ does involve the genetic selection of nerve pathways and networks, what is meant by the ‘nerve-based learning system’ is that dimension or aspect of the nervous system that is to do with understanding cause and effect. This honest but not very explanatory definition of instincts makes this particular difference clear: instincts are ‘a largely inheritable and unalterable tendency of an organism to make a complex and specific response to environmental stimuli without involving reason’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary; see <www.wtmsources.com/144>). The significance of the nerve-based learning system becoming sufficiently developed in humans for us to become conscious and able to effectively manage events, was that our conscious intellect was then in a position to wrest control from our gene-based learning system’s instincts, which, up until then, had been in charge of our lives. Basically, once our self-adjusting intellect, or ability to ‘reason’, emerged it was capable of taking over the management of our lives from the instinctive orientations we had acquired through the natural selection of genetic traits that adapted us to our environment. Moreover, at the point of becoming conscious the nerve-based learning system should wrest management of the individual from the instincts because such a self-managing or self-adjusting system is infinitely more efficient at adapting to change than the gene-based system, which can only adapt to change very slowly over many generations of natural selection. HOWEVER, it was at this juncture, when our conscious intellect challenged our instincts for control, that a terrible battle broke out between our instincts and intellect, the effect of which was the extremely competitive, selfish and aggressive state that we call the ‘human condition’.

An analogy will help further explain the origin of our human condition. (I should mention that a condensation of the explanation of the human condition given in this chapter, in particular some of the ‘Adam Stork’ analogy, was included in chapter 1’s summary of the contents of this book, so the reader should expect some repetition of that material.)