‘FREEDOM’—Chapter 7 Consciousness: What It Is and Its Origins

Chapter 7:3 Why, how and when did consciousness emerge in humans?

As stated at the beginning of this chapter, our self-adjusting conscious mind is a ‘fabulous’ phenomenon, the culminating achievement of the grand experiment in nature that we call life. Unlike the gene-based natural selection system of processing information, where different arrangements of matter with their different properties are compared for their integrative potential, the conscious mind is able to make these comparisons with the information abstracted from its source. The gene-based natural selection process is a form of thinking, of comparing the integrative potential of different arrangements of matter which can be thought of as different ‘ideas’—but that ‘thinking’ or ‘learning’ or ‘refinement’, that experimentation, that ‘selection’ of one ‘idea’ over another, has to be carried out in practise. The conscious mind, however, has the incredible capacity to be able to do this ‘thinking’, this comparing of ‘ideas’, without having to carry them out in practise. Yes, for all the problems it has given rise to, the power of the conscious mind to separate information from its source is fabulous, it has to be nature’s greatest invention.

The obvious question then is how did our wondrously powerful conscious mind emerge from the gene-based natural selection process? To solve problems it’s first necessary to ask the right questions, and in the case of consciousness, the obvious initial question is, ‘Why did humans develop consciousness when other animals haven’t?’ Since consciousness occurs at a certain point in the development of a mind’s efficiency in associating information, and since conscious intelligence—the ability to reason how cause and effect are related, to understand change, to be insightful—would obviously be a very great asset for any animal to acquire, one would assume that fully developed conscious intelligence would have been actively selected for as soon as animals were able to develop a reasonably elaborate central nervous system, and would have thus appeared in many species—and yet it hasn’t. As was described in chapter 6:5, despite this being an obvious assumption, the conventional mechanistic explanation for the emergence of conscious intelligence in humans, and its absence in other animals, is that it occurred as a result of the need to manage complex social situations—for example, in The Social Conquest of Earth, E.O. Wilson wrote that in order ‘to feel empathy for others, to measure the emotions of friends and enemy alike, to judge the intentions of all of them, and to plan a strategy for personal social interactions…the human brain became…highly intelligent’ (2012, p.17 of 330). Termed the Social Intelligence Hypothesis, and occasionally the Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis, this theory (S/MIH) was first formally put forward by the psychologist Nicholas Humphrey in 1976: ‘In broad terms, the MIH was originally developed to explain the special intelligence attributed to monkeys and apes (Humphrey 1976) as adaptations for dealing with the distinctive complexities of their social lives, such as volatile social alliances. The term “Machiavellian” was used by Byrne & Whiten (1988) to capture the central concept of adaptive social manoeuvring within groups made up of companions subject to similar pressures to be socially smart, and the spiralling selection pressures this implies’ (Andrew Whiten & Carel van Schaik, ‘The evolution of animal “cultures” and social intelligence’, Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, 2007, Vol.362, No.1480).

The first point to make is one that was explained in chapter 5 and re-emphasised in chapter 6 (pars 505-509)—that if it wasn’t for the psychologically upset state of the human condition there would be no need to learn, and become intelligent enough to master, the art of managing ‘social’ ‘complexities’. Through the process of love-indoctrination, humans became so instinctively integrated that there was no disharmony/conflict/discord/‘complex[ity]’ to have to manage. Before the emergence of the human condition some 2 million years ago our species lived instinctively as one organism—as the Greeks Hesiod and Plato said (respectively), ‘Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind, free from the toils and anguish of our kind…They with abundant goods ’midst quiet lands, all willing shared the gathering of their hands’, and this ‘was a time…most blessed, celebrated by us in our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come, when we were admitted to the sight of apparitions innocent and simple and calm and happy…and not yet enshrined in that living tomb which we carry about, now that we are imprisoned’; the time when we lived a ‘blessed and spontaneous life…[where] neither was there any violence, or devouring of one another, or war or quarrel among them…In those days…there were no forms of government or separate possession of women and children; for all men rose again from the earth, having no memory of the past [we lived in a pre-conscious state, obedient to our universally loving instincts]. And…the earth gave them fruits in abundance, which grew on trees and shrubs unbidden, and were not planted by the hand of man. And they dwelt naked, and mostly in the open air, for the temperature of their seasons was mild; and they had no beds, but lay on soft couches of grass, which grew plentifully out of the earth’. The pre-human-condition-afflicted, integrated, cooperative, social, ‘calm’, ‘happy’, no ‘quarrel[ling]’, ‘no forms of government’ necessary, free of the divisive selfish and competitive ‘evils to come’, Specie Individual state that the fossil record of our ancestors now evidences, and which largely exists in bonobo society today, simply wasn’t a situation that involved ‘social’ ‘complexities’. No, the bonobos’ harmonious society, and humanity, was borne out of a genuinely altruistic, unconditionally selfless, all-loving, empathetic-towards-others, non-devious, opposite-of-‘smart’-cunning-‘manoeuvring’-‘Machiavellian’ situation.

However, coming back to the obvious question of ‘Why did humans develop conscious intelligence when other animals haven’t?’, as I pointed out in par. 507, while the ability to solve social problems is an obvious benefit of having a conscious mind, all activities that animals have to undertake would benefit enormously from being able to understand cause and effect, so it is completely illogical to suggest that consciousness developed as a result of the need to manage extremely complex social situations. No, any sensible analysis of the question of the emergence of consciousness must be based on the question of ‘What has prevented its development in other animals?’ Consciousness is such a powerful asset for an animal to acquire that something must have blocked its selection in other species. The lack of social situations doesn’t explain why the fully conscious mind hasn’t appeared in non-human species because there was ample need for a conscious intelligent mind prior to the appearance of complex social situations.

It should also be pointed out that while ‘Most contemporary workers in animal cognition, particularly those working with primates, are enthusiastic about the social intelligence hypothesis’ (Kay Holekamp, ‘Questioning the social intelligence hypothesis’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2007, Vol.11, No.2), the hypothesis has at least two flaws that have actually been recognised by human-condition avoiding, mechanistic scientists. Firstly, research has shown that there isn’t a correlation between more complex social groups and greater social learning, which you would expect if the reason for the long mother-infant association was to teach the skills needed to live in complex social groups. For instance, ‘several phenomena have been identified…for which the social intelligence hypothesis cannot account…Evidence of this sort has also accumulated in the literature on primate social intelligence. For example, a comparative analysis found that innovation, tool use and the incidence of social learning in primates co-vary across species and that the frequency of occurrence of social learning is not correlated with group size among primate species’ (ibid). The ‘comparative analysis’ in question says that in regard to primates, ‘social group size and social learning frequency are not correlated’ (Simon Reader & Louis Lefebvre, ‘Social Learning and Sociality’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2001, Vol.24, No.2).

Secondly, evidence that having to manage more complex social situations has not led to greater intelligence is also being furnished through mechanistic science’s studies of relative brain size (which is widely regarded as an indicator of greater intelligence), with research showing that highly social species such as meerkats and hyenas have not developed a larger brain in proportion to body size beyond that of less social species: ‘no association exists between sociality and encephalization [brain size in proportion to body size] across Carnivora [which include meerkats and hyenas] and that support for sociality as a causal agent of encephalization increase disappears for this clade [group]’ (John Finarelli & John Flynn, ‘Brain-size evolution and sociality in Carnivora’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, Vol.106, No.23).

But rather than accepting these fundamental flaws and abandoning the S/MIH, a more sophisticated version of it was actually put forward in 1989 by the biologist Richard Alexander. This refinement, which became known as the ‘Ecological Dominance–Social Competition’ (EDSC) model, holds that a species must first somehow overcome or dominate its environment before the S/MIH can apply, arguing that ‘as our hominin ancestors became increasingly able to master the traditional “hostile forces of nature,” selective pressures resulting from competition among conspecifics [companions] became increasingly important, particularly in regard to social competencies. Given the precondition of competition among kin–and reciprocity–based coalitions (shared with chimpanzees), an autocatalytic [self-fuelling] social arms race was initiated, which eventually resulted in the unusual collection of traits characteristic of the human species, such as…an extraordinary collection of cognitive abilities’ (M.V. Flinn et al., ‘Ecological dominance, social competition, and coalitionary arms races: Why humans evolved extraordinary intelligence’, Evolution and Human Behavior, 2005, Vol.26). While it does not answer the obvious question of why all activities that animals have to manage wouldn’t profit from a conscious intellect, this prerequisite of ‘ecological dominance’ is meant to explain why other species in complex social situations haven’t developed intelligence—apparently because they hadn’t dominated their environment first.

The concept of ‘ecological dominance’ put forward by the EDSC model describes a supposed mastery of the environment achieved, it says, through developments such as tool use, projectile weapons and controlled use of fire that ‘roughly coincided with the appearance of Homo erectus, 1.8 mya [million years ago]’ (ibid). While it is true that conscious intelligence was increasing rapidly during the reign of Homo erectus, as will be revealed in chapter 8:2, conscious intelligence first emerged in our ape ancestor, prior to the emergence of the australopithecines (who appeared some 4 million years ago) and so well before Homo; and further, the dramatic increase in intelligence evident in H. erectus was not a result of ‘ecological dominance’ but, as described throughout this book, a product of psychological factors—as has been the continual increase in conscious intelligence throughout the genus Homo. (It is important to differentiate here that the ‘ecological dominance’ described by the EDSC model is not the same ecologically dominant/beneficial situation our ape ancestors found themselves in when living in the ‘ideal nursery conditions’ that allowed love-indoctrination to develop, which, as was briefly described in chapter 5:8 and as is about to be described in more detail, did have the side effect of liberating conscious intelligence.)

This flaw in the EDSC model’s theory that conscious intelligence did not arise until the emergence of H. erectus because until that time we hadn’t dominated our environment is also evidenced by the fossil record, which shows that brain size dramatically increased in humans before they became ‘ecologically dominant’. Yes, the model’s argument that ‘ecological dominance should arise prior to or along with increases in brain size’ (ibid) is a flaw that even mechanistic, human-condition-avoiding scientists recognise, as this study points out: ‘a great deal of encephalization [brain size relative to body size] occurred before humans were dominant…The EQ [encephalization quotient] of the first instance of Homo, Homo habilis, had already doubled relative to our nearest relatives today, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). These hominins were still largely foragers, scavengers (not yet organized hunters), and prey for more powerful predators’ (R.D. Horan et al., A Paleoeconomic Theory of Encephalization, selected paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Economic Association, San Francisco, Jan. 2009). It certainly doesn’t make sense that developments such as tool use, projectile weapons and the controlled use of fire enabled us to become intelligent because such advancements would have required conscious intelligence to both invent and subsequently manage. Something must have enabled consciousness to emerge, which then allowed us to become clever enough to invent and manage these early technologies.

There are several other theories for how and why humans developed consciousness, including models based around the need to solve problems resulting from climate change, sexual selection for consciousness as an indicator of fitness, and the discovery of cooking, but without being able to acknowledge the human condition, they—as with the S/MIH/EDSC models—are unable to explain in a fully accountable way why consciousness is not a powerful, fitness-assisting asset for an animal to have in all situations (not just social situations).

I should note here that there has been an attempt, using what is called the Expensive Brain Hypothesis, to explain why consciousness has not been widely developed. This theory first equates brain size with intelligence and then claims the reason intelligence has not evolved is because ‘The high proportion of energy necessarily allocated to brain tissue may therefore constrain the response of natural selection to the beneficial impact of increased brain size on an animal’s survival and/or reproductive success’ (Karin Isler & Carel van Schaik, ‘Metabolic costs of brain size evolution’, Biology Letters, 2006, Vol.2, No.4). The fact is, natural selection has the ability to select for an asset if the benefits outweigh the costs, and since consciousness is such an extremely valuable asset, the costs in energy of developing a conscious mind would not, you would expect, be great enough to inhibit its development—after all, natural selection has selected for assets that require an immense amount of energy, such as the males of many species being able to expend colossal amounts of energy during the mating season; consider, for instance, the peacock, which grows an extravagant new train each season, or antelopes engaging in a period of endless and ferocious rutting each year. Another point is that bonobos, who are verging on having developed consciousness, don’t have huge brains like we have. As will be described in pars 707 and 714, what has driven our brain and conscious mind to become so developed is the difficulty of having to try to manage the extreme complexities of our human condition, as evidenced by the fact that the very large brain developed when the human condition developed, which was after the time we became conscious. (Note that in chapter 3:1 I describe how it wasn’t until approximately 2 million years ago that we humans became fully conscious in the sense of being fully cognisant of the situation we humans have been in of having to live under the duress of the human condition.)

The fact is, other animal species have been able to develop all manner of extraordinary mental abilities, many superior to our own, but never full consciousness. (The reason we can know that other animals like dolphins and elephants haven’t developed full consciousness was explained in par. 425.) For instance, in the United States, the nutcracker bird buries around 30,000 nuts throughout the summer months, each in a different location, but come winter and the cover of snow it can recall the location of 90 percent of them. The goby fish can memorise the topography of the tidal flats at high tide so that when the tide retreats it knows the exact location of the next pool to flip to when the one it is in evaporates. And then there is the male common canary, which has a specific part of its brain that expands dramatically every spring so it can learn new mating songs, only to shrink again once the need for it ends at the conclusion of the mating season (just as peacocks shed their tattered tail feathers at the end of the season). So again the question is, if other animals have been able to develop such extraordinary mental abilities, what’s stopping them from developing full consciousness? As will now be explained, the simple and very obvious explanation—if you are not living in denial of the truth of selflessness-dependent, Integrative Meaning—is that genetics is such a selfish process that it will normally block the development of a selflessness-recognising, truthful, effective-thinking conscious mind.

To now explain more fully this obvious—if you are not living in denial—explanation for what has blocked the development of consciousness in almost all species. The explanation begins by re-stating what was pointed out in chapter 4:4, which was that one of the limitations of the gene-based learning system is that it normally can’t select for unconditionally selfless, altruistic, self-sacrificing behaviour because altruistic traits tend to self-eliminate; they tend not to carry on and so normally can’t become established in a species. The effect is that the gene-based learning system actively resists altruistic behaviour. For instance, whenever a female kangaroo comes into estrous, the males pursue her relentlessly. Despite both parties almost falling with fatigue, the chase continues. It is easy to see how this behaviour developed: if a male relaxed his efforts he would lose his opportunity to reproduce. Self-interest is fostered by natural selection with the result that genetic selfishness has become an extremely strong force in animals. It is clear then that there would be no chance of a variety of kangaroo that considered others above itself developing. Unless, of course, they could develop love-indoctrination, but while a kangaroo can look after a joey in its pouch, the pouch is more an external womb, allowing little behavioural interaction between mother and infant. It is the selfless treatment—the active demonstration of love—that trains the infants in selflessness or love. Also, since grass, which they live on, is not very nutritious, kangaroos have to spend most of their time grazing, which leaves relatively little time for social interaction between mother and infant and thus limited training in love.

Genetic refinement normally acts against any inclination towards selfless behaviour because selflessness disadvantages the individual that practises it and advantages the recipients of the selfless treatment—such is the meaning of selflessness. Selflessness normally can’t be reinforced by genetic refinement; indeed, it is emphatically resisted by it. It follows then that in terms of the development of consciousness, the gene-based learning or refinement system was, in effect, totally opposed to any altruistic, selfless thinking. In fact, genetic refinement developed blocks in the minds of animals to prevent the emergence of such thinking. And it is this block against truthful, selflessness-recognising-thinking in the minds of almost all animals that prevents them from becoming conscious of the true relationship or meaning of experience.

To explain more fully how these blocks against selflessness-recognising-thinking developed, an example of how genes resist self-destructive behaviour will be helpful. In what are termed ‘visual cliff’ experiments, newborn kittens are placed on a table and while they will venture towards the edge, they won’t allow themselves to go beyond the edge and fall—a sheet of glass is actually placed over the table to prevent them from accidentally slipping off the edge, but the point is the glass is unnecessary because the kittens instinctively know not to travel beyond the table’s edge. Presumably, this instinctive orientation against doing so evolved because any cat that did venture too close to a precipice invariably fell to its death, leaving only those that happened to have an instinctive block against such self-destructive practices. Natural selection or genetic refinement develops blocks in the mind against behaviour that doesn’t tend to lead to the reproduction of the genes of the individuals who practise that behaviour.

And so just as surely as cats were eventually selected for their instinctive block against self-destruction, most animals have been selected with an instinctive block against selfless thinking because such thinking also tends not to lead to the reproduction of the genes of the individuals who think that way. The effect of this block was to prevent the developing intellect from thinking truthfully and thus effectively.

As pointed out when Integrative Meaning was explained in chapter 4, selflessness or love is the theme of existence, the essence of integration, the meaning of life. While the upset, alienated human race has learnt to live in denial of this truth of the selfless, loving, integrative meaning of existence, it is, in fact, an extremely obvious truth and one that is deduced very quickly if you are able to think honestly about the world. We are, as mentioned, surrounded by integration—every object we look at is a hierarchy of ordered matter, witness to the development of order. It follows then that if you aren’t able to recognise and thus appreciate the significance of selfless Integrative Meaning you are not in a position to begin to think straight and thus effectively; you can’t begin to make sense of experience. All your thinking is coming off a false base and is therefore derailed from the outset from making sense of experience. As stated in par. 220, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote that ‘The discovery of truth is prevented most effectively…by prejudice, which…stands in the path of truth and is then like a contrary wind driving a ship away from land’. You can’t think effectively with lies in your head, especially with such important lies as denial of Integrative Meaning. Your mind is, in effect, stalled at a very superficial level of intelligence with little ability to understand the relationship of events occurring around you.

To elaborate, any animal able to associate information to the degree necessary to realise the importance of behaving selflessly towards others would have been at a distinct disadvantage in terms of its chances of successfully reproducing its genes. It follows then that those animals that don’t recognise the importance of selflessness are genetically advantaged, which means that eventually a mental block would have been ‘naturally selected’ to prevent the emergence of the ability to make sense of experience, to prevent the emergence of consciousness. At this point in development, genetic refinement favoured individuals that were not able to recognise the significance of selflessness, thus ensuring animals remained incognisant, unconscious of the true meaning of life.

Having denied the truth of Integrative Meaning and the importance of selflessness, it is not easy for the alienated human race to appreciate that conscious thought depends on the ability to acknowledge the significance of selflessness/love/Integrative Meaning. However, our own human-condition-induced mental block or alienation is, in fact, the perfect illustration of and parallel for this block in the minds of animals. Unable to think truthfully about the selfless, loving integrative theme of existence, all our thinking has been coming off a false base and, as a result, we too have been unable to think effectively. Alienation has rendered the human race almost stupid, incapable of deep, penetrating, meaningful thought.

So when it comes to thinking truthfully, and thus soundly, humans are now almost as mentally incognisant as animals—a state of affairs that is parodied in the popular animated cartoon Wallace & Gromit. In the series, Wallace is a lonely, sad—alienated—human figure whose dog, Gromit, is very much on an intellectual par with him in his world. Both wear the same blank, stupefied expression as together they muddle their way through life’s adventures. Yes, as R.D. Laing was quoted as saying in par. 123, ‘Our alienation goes to the roots’, there is now ‘fifty feet of solid concrete’ between us and our condemning instinctive self or soul. But to be alienated is to not know you are alienated because if you did you wouldn’t be alienated, you wouldn’t be blocking out the truth—all of which means it will be difficult to accept that humans are now ‘almost as mentally incognisant as animals’, so these further references to just how alienated we have become may help to reveal the extent of our alienation.

Plato, that extraordinary denial-free thinking prophet, wrote that ‘when the soul [our instinctive orientation to Integrative Meaning] uses the instrumentality of the body [uses the body’s intellect with its preoccupation with denial of Integrative Meaning] for any inquiry…it is drawn away by the body into the realm of the variable, and loses its way and becomes confused and dizzy, as though it were fuddled [drunk]…But when it investigates by itself [free of intellectual denial], it passes into the realm of the pure and everlasting and immortal and changeless, and being of a kindred nature, when it is once independent and free from interference, consorts with it always and strays no longer, but remains, in that realm of the absolute [Integrative Meaning], constant and invariable’ (Phaedo, c.360 BC; tr. H. Tredennick, 1954, 79). He also wrote that the ‘capacity [of a mind…to see clearly] is innate in each man’s mind [we are born with an instinctive orientation to Integrative Meaning], and that the faculty by which he learns is like an eye which cannot be turned from darkness [the state of living in denial] to light [the denial-free truth] unless the whole body is turned; in the same way the mind as a whole must be turned away from the world of change until it can bear to look straight at reality, and at the brightest of all realities which is what we call the Good [Integrative Meaning or God]’ (The Republic, c.360 BC; tr. H.D.P. Lee, 1955, 518). Yes, if the human race is to begin to think effectively it has to stop living in denial of Integrative Meaning, ‘the Good’—otherwise our species will stay in the situation where our collective mind, in perpetuity, ‘loses its way and becomes confused and dizzy, as though it were fuddled [drunk/stupid/alienated]’.

While our ‘capacity’ ‘to see clearly’ is, as Plato said, ‘innate’, denial and its alienating effects came about through our own corrupting search for knowledge and through our encounter with the already upset, human-condition-afflicted, corrupt world. And just as this search for knowledge and our encounter with the upset world began at birth and continued throughout our lives, the extent of our insecurity about our corrupted state and associated block-out or alienation also increased throughout our lives, until eventually we were walking around free, in effect, of criticism but totally inebriated in terms of our access to truth and meaning. So it follows that it was when humans were very young that they were most able to think truthfully. The famous psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud recognised this when he said, ‘What a distressing contrast there is between the radiant intelligence of the child and the feeble mentality of the average adult’ (The Freud Reader, ed. P. Gay, 1995, p.715). Christ also recognised the mental integrity of the young when he said, ‘you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children’ (Bible, Matt. 11:25). Albert Einstein famously echoed these sentiments when he noted that ‘every child is born a genius’, while the philosopher Richard Buckminster Fuller acknowledged that ‘There is no such thing as genius, some children are just less damaged than others’ (NASA Speech, 1966), and that ‘All children are born geniuses. 9999 out of every 10,000 are swiftly, inadvertently de-geniused by grown-ups’ (Mario M. Montessori Jr, Paula Polk Lillard & Richard Buckminster Fuller, Education for Human Development: Understanding Montessori, 1987, Foreword). R.D. Laing also observed that ‘Each child is a new beginning, a potential prophet [denial-free, truthful, effective thinker]’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p.26 of 156) and pointed out that ‘Children are not yet fools, but [by our treatment of them] we shall turn them into imbeciles like ourselves, with high I.Q.’s if possible’ (ibid. p.49).

Many exceptionally creative people have also made statements to the effect that genius is the ability to think like a child. For example, one of the most accomplished artists of all time, Pablo Picasso, famously said about his struggle to paint well that ‘It’s taken me a lifetime to learn to paint like a child.’ The poet Charles Baudelaire similarly wrote that ‘genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will’ (The Painter of Modern Life, 1863), while the Chinese philosopher Mencius said, ‘The great man is he who does not lose his child’s heart, the original good heart with which every man is born’ (The Works of Mencius, Book 4 ch.12, c.371-289 BC). And just like the already mentioned quotes about our alienated condition by Samuel Beckett that ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’, and R.D. Laing that ‘To adapt to this world the child abdicates its ecstasy’, the artist Francis Bacon said ‘the shadow of dead meat is cast as soon as we are born’ (The Australian, 15 Jun. 2009, reprinted from The New Republic). Similarly, in the 1993 film House of Cards, one of the characters makes the following intuitive comment about how sensitive and vulnerable innocent children have been to the horror of the alienated world of adults: ‘I used to watch Michael [a character in the film] about two hours after he was born and I thought that at that moment he knew all of the secrets of the universe and every second that was passing he was forgetting them [he was having to live in denial of them]’ (based on a screenplay by Michael Lessac). The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was another who decried the fate of adult humans when he wrote that ‘Our boat [our being] is asleep on Serchio’s stream, its sails are folded like thoughts in a dream’ (The Boat on the Serchio, 1821). The Bible also offers this account of our estranged, resigned adult condition: ‘This people’s heart has become calloused [alienated]; they hardly hear with their ears, and they have closed their eyes’ (Isa. 6:10 footnote). And in his incredibly honest poem Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood, William Wordsworth provided this description (which was referred to in par. 182) of how quickly humans become alienated from our all-sensitive and truthful, innocent instinctive self or soul: ‘There was a time when meadow, grove, and streams / The earth, and every common sight / To me did seem / Apparelled in celestial light / The glory and the freshness of a dream / It is not now as it hath been of yore / Turn wheresoe’er I may / By night or day / The things which I have seen I now can see no more // The Rainbow comes and goes / And lovely is the Rose / The Moon doth with delight / Look round her when the heavens are bare / Waters on a starry night / Are beautiful and fair / The sunshine is a glorious birth / But yet I know, where’er I go / That there hath past away a glory from the earth // …something that is gone / …Whither is fled the visionary gleam? / Where is it now, the glory and the dream? // Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star / Hath had elsewhere its setting / And cometh from afar / Not in entire forgetfulness / And not in utter nakedness / But trailing clouds of glory do we come / From God, who is our home / Heaven lies about us in our infancy! / Shades of the prison-house begin to close / Upon the growing Boy / …And by the vision splendid / Is on his way attended / At length the Man perceives it die away / And fade into the light of common day / …Forget the glories he hath known / And that imperial palace whence he came’ (1807). The prophet Job similarly recognised that under the duress of the human condition ‘Man…springs up like a flower and withers away; like a fleeting shadow, he does not endure’ (Job. 14:1-2).

So it is widely appreciated that while children have wonderful imaginations, that creativity is often lost by the time they reach adulthood—but with understanding of both the human condition and the different roles played by the left and right hemispheres of our brain we can understand why. In the human brain, one hemisphere (the right) specialises in general pattern recognition while the other specialises in specific sequence recognition. The right is lateral or creative or imaginative, while the left is vertical or logical or sequential. The right has even been described as intuitive, thoughtful and subjective and the left as logical, analytical and objective. One stands back to ‘spot’ any overall emerging relationship while the other goes right in to take the heart of the matter to its conclusion. We need both because logic alone could lead us up a dead-end pathway of thought. For example, we can imagine that for a while our thinking mind could have assumed that the most obvious similarity between fruits was that they were brightly coloured; however, with more experience the similarity that proved to have the greatest relevance in the emerging overall picture was their edibility. When one thought process leads to a dead-end our mind has to backtrack and find another way in: from the general to the particular and back to the general, in and out, back and forth, until our thinking finally breaks through to the correct understanding. The first form of thinking to wither from Resignation and alienation was imaginative thought because wandering around freely in our mind all too easily brought us into contact with unbearable human-condition-confronting truths such as Integrative Meaning. On the other hand, if we got onto a logical train of thought that at the outset did not raise criticism of us there was a much better chance it would stay safely non-judgmental. So children have always had wonderful imaginations because they had yet to learn to avoid free/open/adventurous/lateral thinking; they had yet to resign themselves to living a separated-from-the-truth, in denial of the issue of the human condition, alienated existence.

So adults have become immensely alienated, not wanting to think truthfully and thus unable to think effectively. Indeed, we have become so alienated that we will readily intellectually focus on a safely sectioned-off area of inquiry or activity—such as solving a maths equation, or mastering a computer problem, or debating whether God has been destroyed by the big bang theory of the origins of the universe, or ordering our wardrobe, or polishing our car, or making a cake, or even sending man to the Moon—and yet we won’t go beyond those safety limits and risk encountering anything to do with the issue of ‘self’, the depressing subject of the human condition. In fact, mechanistic science is just such a reduced, deeply afraid, don’t-want-to-look-at-the-big-picture, lose-yourself-in-tiny-little-details, sharpen-your-pen-scratch-your-ear-fix-that-little-problem-over-there-don’t-think-don’t-think-don’t-think, neurotic activity. The more neurotic a person, the smaller their world becomes. And as will be explained in chapter 8:16C, in the extreme case of upset, that of the autistic mind, it becomes completely detached.

The genesis of this disconnection in the resigned, human-condition-avoiding, neurotic mind from any form of truthful, meaningful, integrated, effective thinking was perfectly described by the psychologist Arthur Janov in the extract of his that was included earlier in par. 221, but which is so relevant here I am re-including it again in part (underlinings are my emphasis): ‘As the child becomes split by his Pain [caused by his encounter with the human condition], he will develop philosophies and attitudes commensurate with his denials. He will have a warped view of the world…Thus, intellect becomes the mental process of repression…The more reality a person is forced to hide in his youth, the more likely it will be that certain areas of thinking will be unreal. That is, it is more likely that thought process will be constricted so that generalised extrapolations cannot be made about the nature of life and the world. Conversely, to be free to articulate one’s feelings while growing up will lead to becoming an articulate, free-thinking person, unhampered by fear, which paralyses thought…A young child can split from his feelings [from his Pain, the human condition] and learn every aspect of engineering. He can be a “smart” engineer or scientist…His intellect is something apart from his feelings…Neurotic intellect is an order superimposed on reality…He is truly a specialised man, living in his head because his body [where his feelings/pain/hurt soul lives] is out of touch and reach. He will deal with each piece of news he hears as an isolated event, unable to assemble what he sees and hears into an integrated view. Life for him is a series of discrete events, unconnected, without rhyme or true meaning’ (The Primal Revolution, 1972, pp.158-160 of 246). In short, the human-condition-afflicted brain is one that ‘paralyses thought’.

It’s an extraordinary—indeed, mad—situation, this one where humans are unable to think on any substantial, effective scale, and one that General Omar Bradley saw the ramifications of when, as mentioned in par. 226, he said that ‘The world has achieved brilliance…without conscience. Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants.’

Yes, we can wrestle with and assemble this bit and that bit of our world but we can’t look at and deal with the big subject of the human condition. So in terms of the all-important issue of what needs to be done about the state of the world, and in particular our species’ plight, while we will apply all our vigour to protesting an environmental cause or the rights of an indigenous ‘race’ or the demand for peace, or any one of a number of other ‘makes-you-feel-you-are-doing-good-but-actually-totally-superficial’ so-called politically correct causes, we will not look at the nightmare of angst in ourselves, the real devastation and issue of our own condition and, beyond that, the human condition that needs to be addressed if we are to bring about a caring, equitable and peaceful world—because the fact is, no matter how much we try to restrain and conceal our upset eventually our world will become an expression of ourselves and thus as devastated as we are. To fix the world we have to first fix ourselves.

As will be made very clear in chapter 8:16O, the truth is that the main function of politically correct causes has been to allow upset humans to feel that they are doing good when they are actually avoiding what is required to make a positive difference—namely confronting the issue of the human condition. Human life has been preoccupied with maintaining the many delusions and false ways of making us feel good about ourselves and with all manner of escapisms from reality rather than with the meaningful thinking and progressive actions we claim it is.

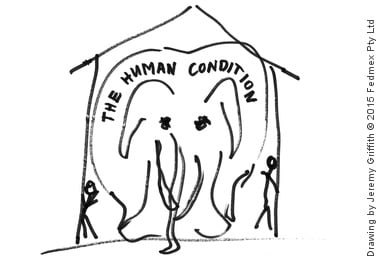

In short, the human condition is the all-important issue that had to be looked at to free ourselves from our condition and truly bring peace to our world and yet it is the one issue we have refused to look at. As Carl Jung recognised, ‘Man everywhere is dangerously unaware of himself. We really know nothing about the nature of man, and unless we hurry to get to know ourselves we are in dangerous trouble’ (Laurens van der Post, Jung and the Story of Our Time, 1976, p.239 of 275). R.D. Laing also recognised this when he wrote that ‘The requirement of the present, the failure of the past, is the same: to provide a thoroughly self-conscious and self-critical human account of man’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967, p.11 of 156). The human condition is the proverbial elephant in our living rooms that we pretend not to see, the all-important issue that we assiduously practise denying.

The examples of our extremely escapist, extremely superficial, indeed, extremely separated or alienated from any deep, meaningful, truthful, effective thinking are endless, but what all this alienation that now exists in the minds of adult humans shows is that the human mind has been twice alienated from the truth in its history: once when we were like other animals, instinctively blocked from recognising the truth of selflessness, and again in our present state, in which we are terrified of the issue of our selfish and divisive human condition and as a result are living ‘a long way underground’ in Plato’s dark ‘cave’ of denial of the significance of the selfless, loving integrative meaning of existence. Yes, other animals are unable to think truthfully and thus effectively because they can’t recognise the truth of selflessness, and under the duress of the human condition we too have been incapable of effective thought because we haven’t been able to recognise the truth of the selfless meaning of existence.

But while humans have gradually retreated from consciousness into virtual unconsciousness because of our insecurity about our non-ideal, soul-corrupted, ‘fallen’, selfish, competitive and aggressive human condition, we are, to our knowledge, the first species to become fully conscious. So, the next question is, how were our ape ancestors able to overcome the block that exists in the minds of the great majority of animals and become capable of making sense of experience, become conscious? (As mentioned in par. 511, all animals are trying to develop love-indoctrination and to what degree they have been able to develop it will dictate to what degree they have been able to develop at least a rudimentary level of consciousness, but no other existing species has developed full consciousness like humans have, and bonobos almost have.)

Understanding how the nurturing love-indoctrination process was able to develop selfless, moral instincts in our ape ancestors (and to some degree in some other primates today) allows us to answer this crucial question, because the reason we were able to become fully conscious is that the nurturing of selfless instincts breached the block against thinking truthfully by superimposing a new, truthful, selflessness-recognising mind over the older, effectively dishonest, selfless-thinking-blocked one. Since our ape ancestors could develop an awareness of cooperative, selfless, loving meaning, they—and, by extension, humans—were able to develop truthful, sound, effective thinking and so acquired consciousness, the essential characteristic of mental infancy.

To use a comparative example, chimpanzees are currently in a relatively early stage of mental infancy—they have the conscious mental powers of approximately a two-year-old human and demonstrate rudimentary consciousness, in that they are beginning to relate information or reason effectively and make sufficient sense of experience to recognise that they are at the centre of the changing array of events they experience. Experiments have shown that they have an awareness of the concept of ‘I’ or self and, as mentioned earlier, are capable of reasoning how events are related sufficiently well to know that they can reach a banana tied to the roof of their cage by stacking and climbing upon boxes.

In the case of bonobos, evidence suggests that this species is the most intelligent or conscious next to humans—as is apparent in these quotes that were referred to in pars 426-428: ‘Everything seems to indicate that [Prince] Chim [a bonobo] was extremely intelligent. His surprising alertness and interest in things about him bore fruit in action, for he was constantly imitating the acts of his human companions and testing all objects. He rapidly profited by his experiences…Never have I seen man or beast take greater satisfaction in showing off than did little Chim. The contrast in intellectual qualities between him and his female companion [a chimpanzee] may briefly, if not entirely adequately, be described by the term “opposites”’ (Robert M. Yerkes, Almost Human, 1925, p.248 of 278). Sue Savage-Rumbaugh reinforced this view when she wrote that ‘Individuals who have had first hand interactive experience with both Pan troglodytes [chimpanzees] and Pan paniscus [bonobos or pygmy chimpanzees] (Yerkes and Learned, 1925; Tratz and Heck, 1954) have been left with the distinct impression that pygmy chimpanzees are considerably more intelligent and more sociable than Pan troglodytes’ and that ‘Each individual who has worked with both species in our lab is repeatedly surprised by their [bonobos’] communicative behavior and their comprehension of complex social contexts that are vastly different from anything seen among Pan troglodytes’ (‘Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes: Contrasts in Preverbal Communicative Competence’, The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, pp.396, 411-412 of 435). The following extract demonstrates how extraordinarily aware, cooperative, empathetic and intelligent bonobos are: ‘Barbara Bell…a keeper/trainer for the Milwaukee County Zoo…works daily with the largest group of bonobos…in North America…“It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day,” she [Bell] says. “They’re extremely intelligent…They understand a couple of hundred words,” she says. “They listen very attentively. And they’ll often eavesdrop. If I’m discussing with the staff which bonobos (to) separate into smaller groups, if they like the plan, they’ll line up in the order they just heard discussed. If they don’t like the plan, they’ll just line up the way they want.” “They also love to tease me a lot,” she says. “Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh. But what really blows me away is their ability to understand a situation entirely.” For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. “They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go,” says Bell. “That’s pretty amazing. Adults demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other”’ (Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998). More recently, the bonobo researcher Vanessa Woods described bonobos as ‘the most intelligent of all the great apes’ (‘Bonobos – our better nature’, blogs.discovery.com, 21 Jun. 2010; see <www.wtmsources.com/134>).

Again, as was explained in par. 429, there are some scientists who suggest that chimpanzees are as intelligent as bonobos, but there is an undeniable freedom in the mind of a bonobo that is apparent in their capacity to be interested in the world around them, and in their empathy, compassion and even simple, childish humour, as evidenced by the quotes above. While it is true that chimpanzees show a mental dexterity, it is a narrow, opportunistic, self-interested mental focus (similar to a very primitive version of the alienated, deadened minds of humans today), not the broad, free, open, curious, aware, all-sensitive, loving, truly thoughtful, conscious mind that bonobos have. It does have to be remembered that mechanistic science doesn’t even have an interpretation of the word ‘love’, so we can’t expect it to be capable of showing interest in or acknowledging the kind of open, curious, aware, all-sensitive and loving conscious mind that bonobos have. Indeed, the extraordinarily cooperative, unconditionally loving and truly aware characteristics of bonobos would motivate, and indeed (as we saw in chapter 6) have motivated, human-condition-avoiding, alienated mechanistic scientists to find a way to demote them at every opportunity, just like they found a way to demote my work and that of Dian Fossey and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh.

So how did the process of nurturing overcome the instinctive block against selfless thinking/behaviour? It makes sense that at the outset the brain of our ape ancestors was relatively small with a limited amount of association cortex, the brain matter in which information is associated. These brains had instinctive blocks preventing the mind from making deep meaningful/truthful/selflessness-recognising perceptions. At this stage, however, these small, inhibited brains were being trained in selflessness, so although there was not a great deal of unfilled cortex available, what was available was being inscribed with a truthful, effective network of information-associating pathways. The mind was being taught the truth and given the opportunity to think clearly, in spite of the existing instinctive blocks or ‘lies’. While at first this truthful ‘wiring’ would not have been very significant due to the small size of the brain, it had the potential for much greater development. Further, as was explained in par. 390, with this selfless training of the brain occurring over many generations, the selfless ‘wiring’ in the brain would have gradually become instinctive or innate. Genes would inevitably follow and reinforce any development process—in this they were not selective. The difficulty lay in getting the development of unconditional selflessness to occur, for once it was regularly occurring it would naturally become instinctive over time, which it did—our instinctive moral soul, the ‘voice’ of which is our ‘conscience’, was formed. We are born with a brain that has instinctive orientations that incline us to behave unconditionally selflessly, and to expect to be treated in the same way—as Ashley Montagu wrote, ‘to live as if to live and love were one is the only way of life for human beings, because, indeed, this is the way of life which the innate nature of man demands’.

Thus, the mind was trained or programmed or ‘brain-washed’ or ‘indoctrinated’ with the ability to think in spite of the blocks working against such training; it had, at last, been stimulated by the truth. Of course, it must be remembered that in this early stage of development the emphasis was on training in love, not on the liberation of the conscious ability to think, which was incidental to Negative Entropy’s push for our ape ancestors to become an integrated group of multicellular animals; but, once fully liberated, the conscious mind takes on a life of its own, it is free to develop—and that development follows an inevitable path.

Yes, after assisting the love-indoctrination process by allowing for the conscious selection of less aggressive mates, the fully conscious mind progresses down its own particular path of development. As summarised earlier, and this will be elaborated upon in some detail in chapter 8, this journey kicks off in the infancy stage, during which the conscious mind is sufficiently aware of the relationship of events that occur through time to recognise that the individual doing the thinking is at the centre of the changing array of experiences around it. It is during infancy that the conscious individual becomes aware of the concept of ‘I’ or self, which is what bonobos and, to a lesser degree, the other great apes are capable of. Infancy is also when the individual discovers conscious free will, the power to manage events. Childhood is the stage when the conscious individual revels in this free will, ‘playing’ or experimenting with it, while adolescence is the stage during which the conscious individual encounters both the sobering responsibility of free will and the agonising identity crisis brought about by the conflict with the already established instinctive orientations and the dilemma that results, which, in the case of humans, we call the human condition—the question of whether or not we are meaningful beings. Adulthood is when the conscious mind ends the insecure stage of adolescence by finding understanding of that corrupted condition, which is the mature, transformed state that humanity can, if it chooses correctly between terminal alienation and transformation, now enter.

Of course, as was pointed out at the end of chapter 6, this explanation of the origin of consciousness was always going to be an extremely difficult explanation for mechanistic science to appreciate because it depends on recognising so many truths that have historically been denied. To arrive at this explanation of how consciousness emerged and then developed into the highly intelligent brain humans have today hinges on being able to recognise the truth of Integrative Meaning and its theme of unconditional selflessness—and from there why animals would have developed blocks in their minds preventing selfless, truthful, effective thinking and thus consciousness—and from there how the nurtured training of selflessness in humans would have liberated truthful thinking and thus consciousness—and from there how the emergence of consciousness would have led to a terrible battle with our instinctive self—and from there how the psychological upset that resulted from the battle would have demanded a more developed, intelligent, bigger brain in order to find understanding of why we had become divisively behaved. The journey has involved so many unbearably confronting truths that it is not surprising that the human-condition-avoiding mechanistic paradigm has found it difficult to acknowledge. It also reveals how if you are living in denial of truth you have no chance of making sense of our world and place in it—as evidenced by the mountain-high pile of books that have been written about consciousness without ever managing to penetrate the subject. So, sadly, the President of the United States Barack Obama’s 2013 ‘Brain Initiative’, which will see ‘$100 million initial funding’ going to human-condition-avoiding, denial-committed, mechanistic science to find ‘the underlying causes of…neurological and psychiatric conditions’ and ‘develop effective ways of helping people suffering from these devastating conditions’, namely the human condition (and as described in par. 603, there are very similar initiatives occurring in Europe), is so self-defeating it is, in effect, nothing more than an act of pure desperation.

In summary, it was the process of nurturing love-indoctrination that not only gave our species its instinctive orientation to behaving cooperatively—our moral soul—it also liberated consciousness in our forebears. As pointed out in chapter 5, since nurturing is largely a female role and females controlled the selection of cooperative mates, it is true to say that the female gender created humanity. Throughout humanity’s infancy and childhood, a period of time that, as will be explained in the next chapter, lasted from some 12 to 2 million years ago, nurturing played the most important role in the group; it was a matriarchal society in which males had to support this focus on nurturing and protect the group from external threats. However, as will also be described in the next chapter, humanity’s matriarchal structure came to an end when our ignorant, ideal-behaviour-demanding instinctive self began to criticise our conscious mind’s search for knowledge and men, in their role as group protectors, had to take up the battle of resisting that naive, idealistic criticism from our instinctive self that was threatening to stop the maturation of humanity from ignorance to enlightenment. At this point, the patriarchal society that has existed for the last 2 million years came into being.

What now needs to be presented is a description of all the psychological stages that our conscious mind progressed through in that heroic journey from ignorance to enlightenment.

(A more complete description of the nature and origins of consciousness can be found in Freedom Expanded at <www.humancondition.com/freedom-expanded-consciousness>.)